Singing Songs of Piccadilly: Review

– Editors

Niall Hobhouse writes about The Buildings of Green Park by Andrew Jones. To purchase the book, click here.

Green Park, a pair of anecdotes:

1.

Queen Caroline – ‘What would it cost, Sir Robert, to close the Park to the public?’

Walpole – ‘May it please your Majesty, but Three Crowns – your own, your husband’s and your son’s’

2.

In the late 1960’s Cedric Price and his AA students obtain a change-of-use order for Buckingham Palace, on the grounds of ‘underuse’; they propose the Palace should be repurposed as a youth hostel. This prompts a change in the law, requiring planning applicants in future to prove ownership of the property that is the subject of their application. (Later, the same studio suggests that new public housing should replace every building facing Green Park between Piccadilly and Pall Mall – from the Ritz to Lancaster House (said Queen Victoria to the Duchess, ‘I come from my House to your Palace’)

It is a luxury for us to be equally comfortable on both sides of all these arguments (The Hanoverian monarchy and the GLC certainly held quite different ideas of who, or what, might be identified as the Public). However tongue-in-cheek, they do neatly encapsulate the uneasy politics of public space in England since the early 18th century. For a small island, with a growing population and economy, the Picturesque was the device that commodified the view, and set the terms on which it was to be shared.

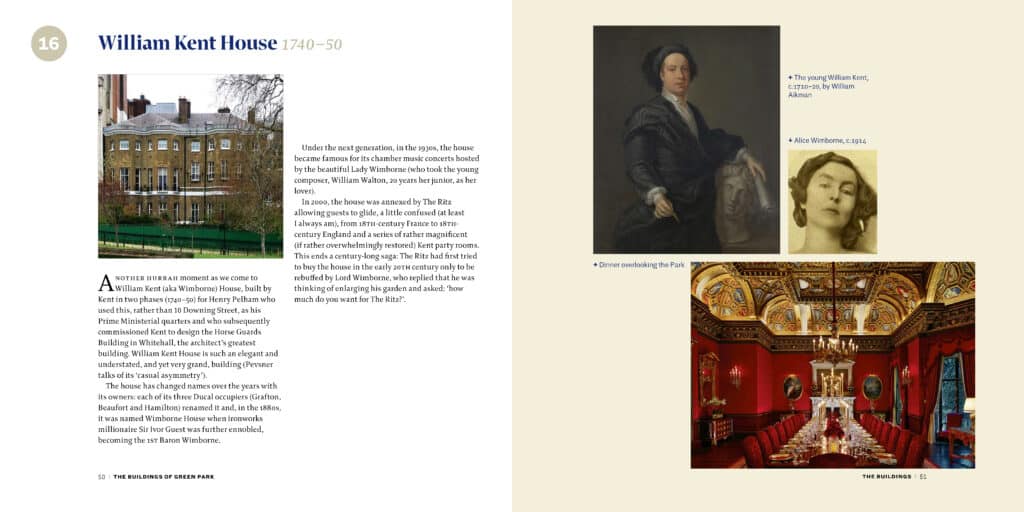

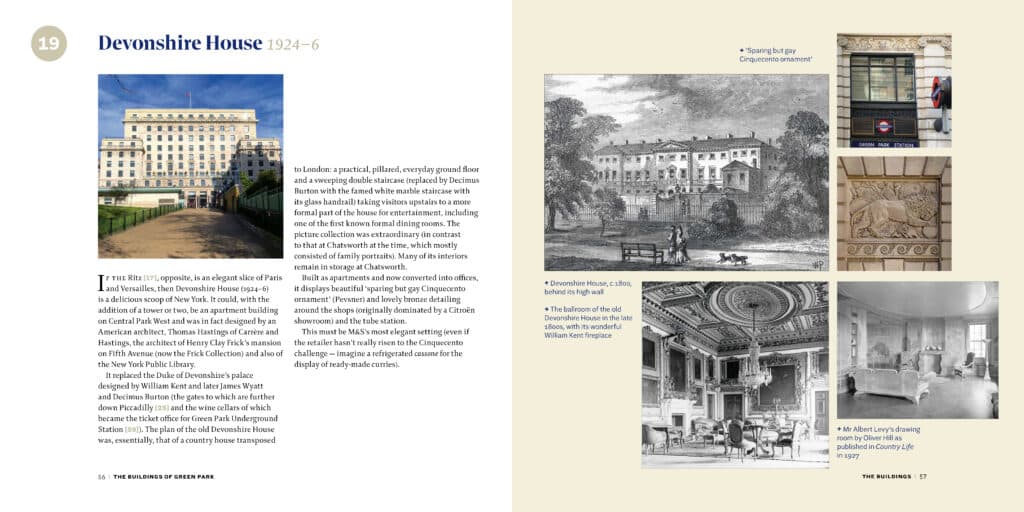

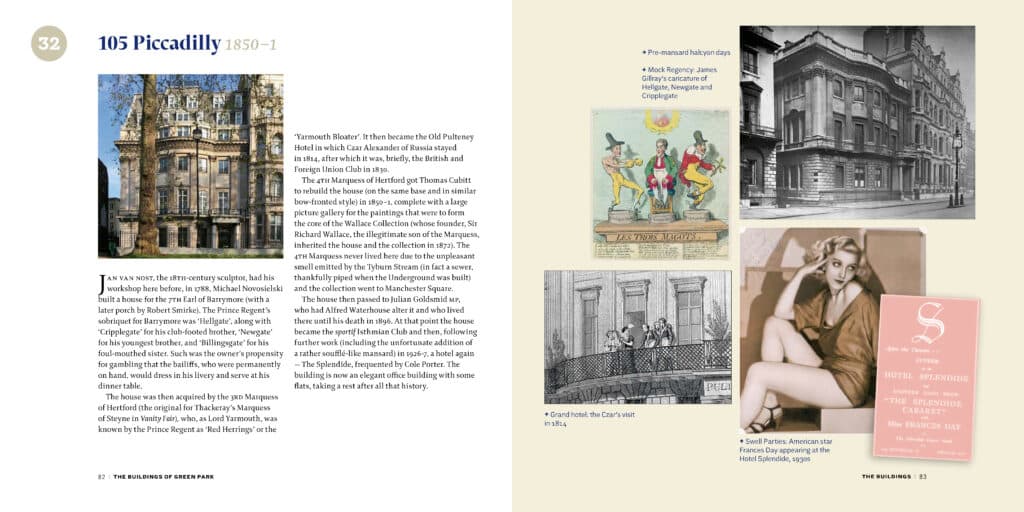

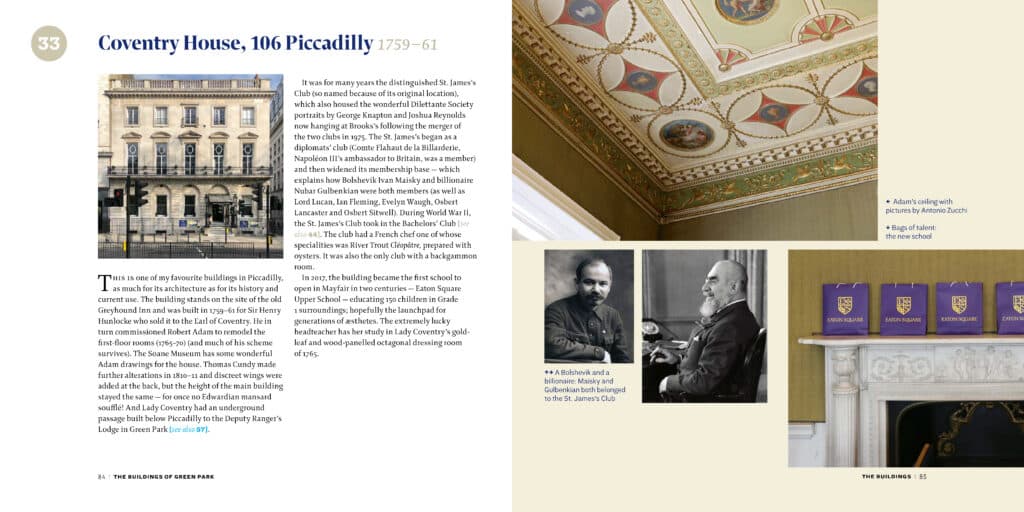

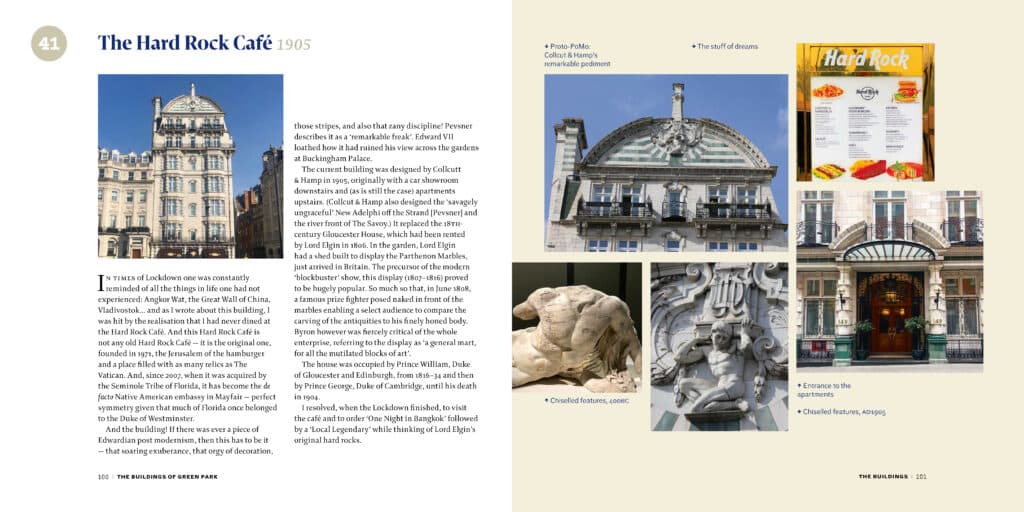

The two stories also make neat bookends to Andrew Jones’s wonderful tour of the buildings of Green Park. In equal parts a social and an architectural history, the book starts with a building-by-building account of all the extraordinarily rich frontage that Cedric would have replaced with tower blocks. Jones then continues his walk along Piccadilly as far as Apsley House, recounting both the histories of famous inhabitants and the earlier houses that stood there; he caps his tour with descriptions of the ragtag monuments and memorials that litter the park itself.

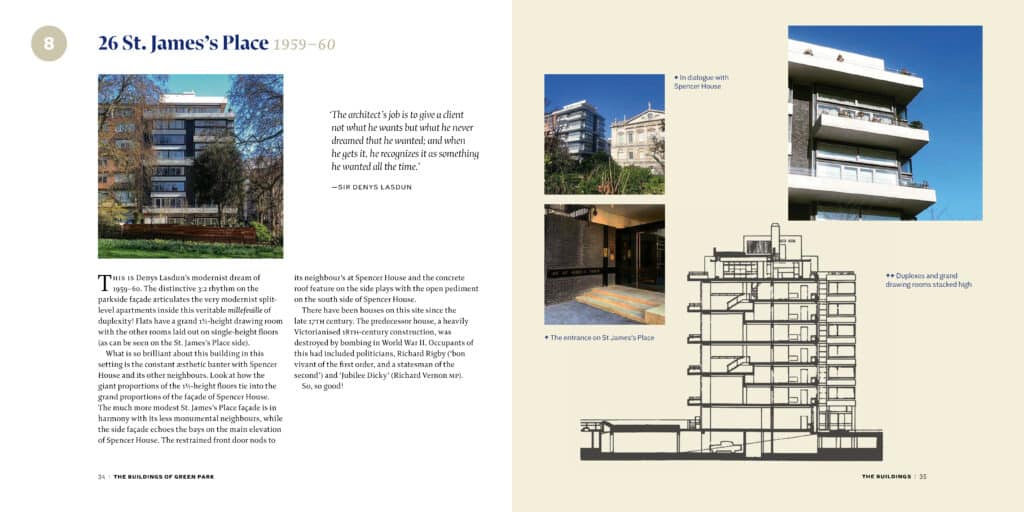

The view of Green Park (known earlier as Upper Saint James’s Park) has been fought over by the British for longer, and far more ferociously, than a glimpse of the sea in Menton; the battle has been challenging for client and architect alike. The disproportionate value of the plot licenced extravagant schemes and, as fashion changed, casual demolitions; and it placed an extraordinary premium on the street entrances offered by Arlington Street and Saint James’s Place. By the 1880’s, and towards Park Lane, the pressure was on – to build higher and to accept narrower façades; throughout, overpriced frontage has driven radical solutions to internal circulation and organization that culminate in 1960, with Denys Lasdun upending of the piano nobile of Spence House in his great block of duplex flats next door.

With an introduction by Alain de Botton, and photographs by the author and his wife, the artist Laura Hodgson, the project is the engaging product of a life upended by the pandemic. Trapped (is that really the word?) in his own apartment overlooking the park, Jones occupied himself with a series of precisely researched, and wildly popular, Instagram posts. As the months of lockdown extended, he was persuaded to turn these into a book. Now in print, his descriptions retain all the cryptic immediacy of the strange circumstances – and of the medium – in which they were conceived.

– Philippa Lewis