Open Wide / Wide Open

We started with six words:

a short-term dwelling for an artist

then added:

with a child

What adaptations have you made to your domestic space since having a child? / What adaptations have you made to your work space since having a child? / How / When / Where do you work? / What arrangements for sleeping do you have with your child? / How do these change (over the course of a night/as they have grown older)? / How do you cook for your child? / Do you eat together? / What do you do when you need some privacy?

In 2019, I conducted a series of interviews with six female artists [1] who had recently become mothers. These women were caring and working from home. In the conversations we thought through how they had adapted their work/home environments, and questioned what limitations they had encountered within the spaces in which they were raising their children while maintaining their practices.

The interviews became a series of drawings that contributed to a body of research undertaken as part of an all-female research and development team for the design of a dwelling on grounds of Grizedale Arts in Cumbria. The project was born out of a desire to practically address two distinct, but intertwined, complications relating to women, building and work:

1. The spatial needs of a practicing artist-mother.

2. The lack of women in building as demonstrated by the persistent percentage (unchanged since 1980) of 1% women working with tools on site.

These two concerns were the starting point by which to trace the histories of women in the manual trades and wider labour movements, and glean from feminist self-build projects, practices, and collectives, applying then to now.

The existing site of the brief was a 9m by 3m off-the-peg agricultural building. Erected in 2009, it has lived as an office, a pottery and a storage shed. It was to become both home and workplace for an artist-mother on residency for a period of weeks or months.

Our approach was from inside to out, moving from micro to macro, between lips and ears. We mapped the flora and fauna that occupied the building’s edges, invited visitors from the local community to manipulate its layout and, most pertinent here, interviewed past and future inhabitants. Daily routines were made to resound in an attempt to override the resistance for recollection in the everyday practice of architecture. [2]

Words became a tool for gathering. Drawing a tool by which to digest. Through these practices we built a strategy by which to assemble an alternative brief; one fed by first hand experience and digested through drawing. A tool to flip client-user to user-client, to move us to thinking about the future building from inside out, and to throw things wide open.

The interviews began to repeat on us.

‘A good size bed that fits two adults and a kid is always useful even if you don’t co-sleep or you are single.’

wide

‘Moving house entirely. From a small flat on a busy main road in London to a suburban home town … The house we chose, crucially has open living space, so that, for example, cooking a meal and talking to a playing child can be done simultaneously… [extended beyond interior] with large double doors that open onto the garden.’

wide, open

‘Totally minimalised my space for sanity. I am not typical on this point but for me sanity since having kids has been spending as much time outdoors as possible. My domestic space has become somewhere I sleep and work in and prepare food… less furniture the better. We even eat on the floor. No cutlery either.’

wide, open, empty

These six women were living within inherited architectures; in both rural (west Wales, Cumbria and Sussex) and urban contexts (Berlin, Athens and Southampton). With their exterior forms set solid two options were available; extend outside, alter indoors. So to parks, play spaces and gardens, then after dark back inside where they perforate, cushion and clad. Interventions that would appease and control issues of light, noise, physical discomfort and mess.

Curtains, blinds and coloured bulbs to expand and contract light and dark. Noise leakage to be tempered by using traditional architectural fittings in combination with technology; a baby monitor allowed doors to be closed, subtitles allowed films to be viewed. Soft furnishing, cushions, pillows, and blankets everywhere to aid with the comfort and safety of the mother’s and child’s bodies. The stuff of parenthood was answered with boxes and drawers and baskets.

‘personally I really like to return my domestic space to grown-up space at the end of the childcare day. So having adequate storage is really nice and useful for easily being able to put toys and mess away at the end of the day.’

empty

‘doors are mainly kept closed (an open plan space would require some kind of divide or a baby prison (I call it that but it’s called a play pen) we have a wooden one that can also be used to divide the room or be formed in an octagon to close her in. I use it when on my own and I need to leave her in the room on her own.’

empty, open

What do you do when you need some privacy? ‘Shut bedroom door, hide in bathroom or go to hut.’

empty, open, closed

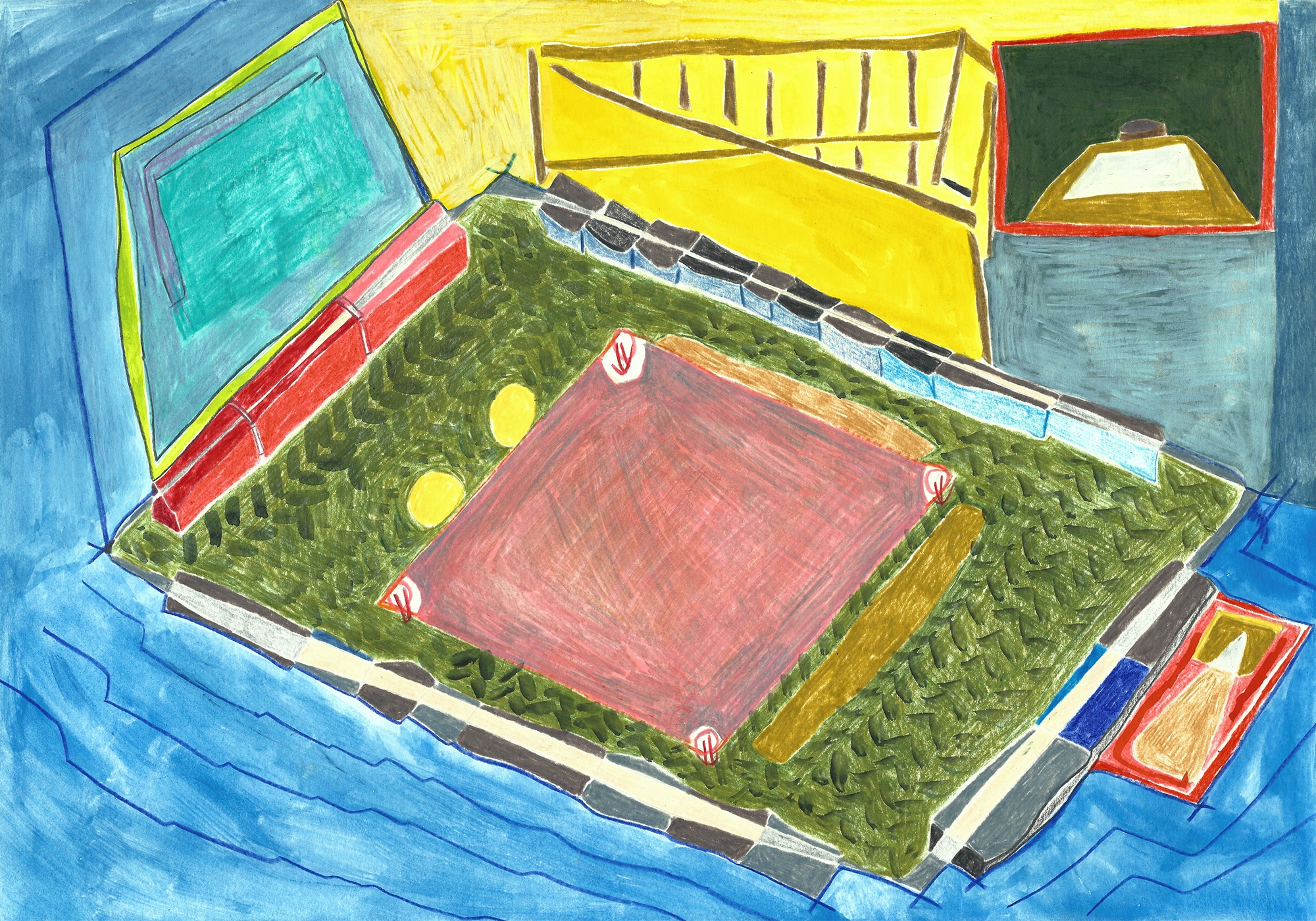

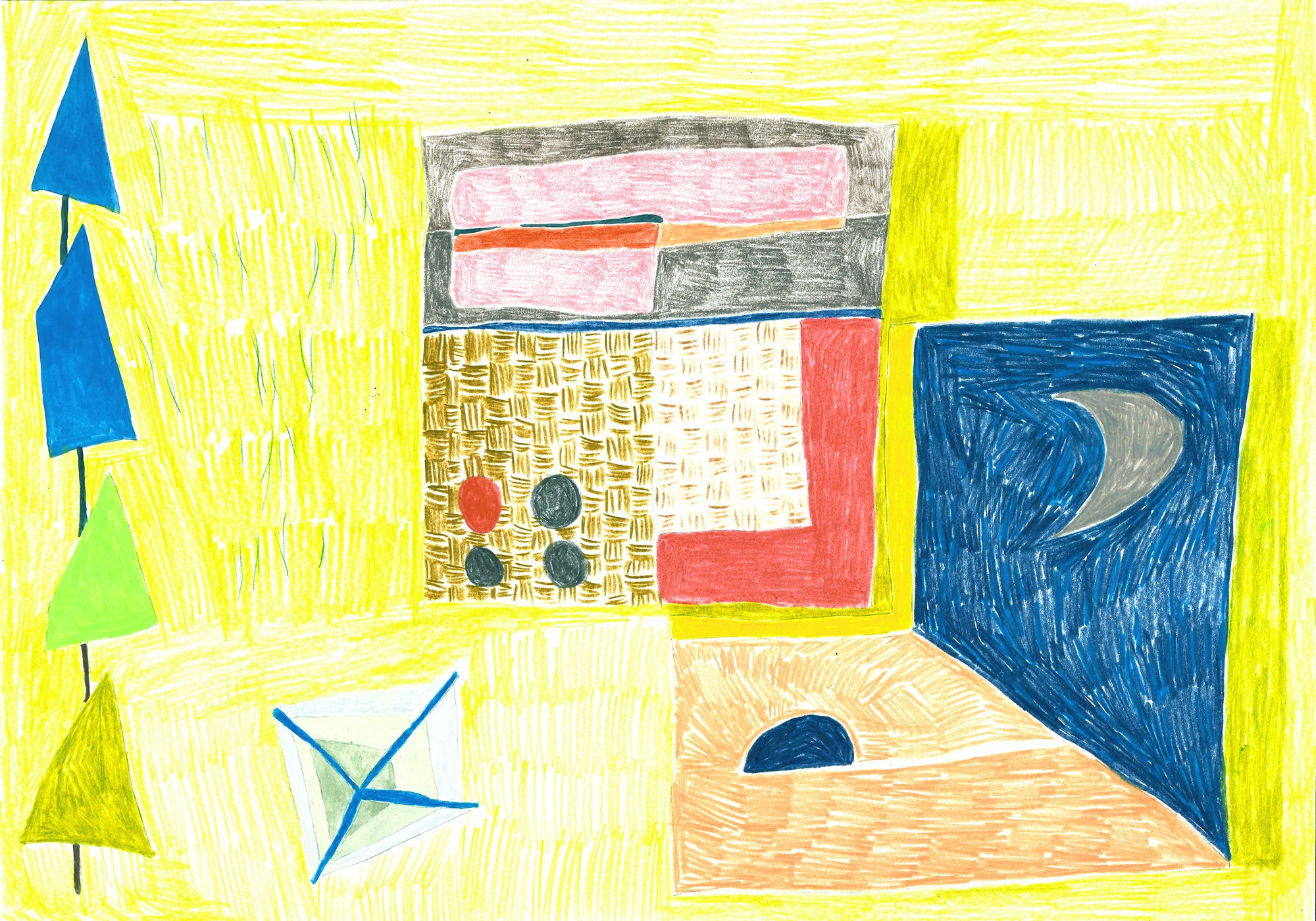

For each transcript I made a drawing using pencil and gouache. These drawings translated the issues and adaptations onto the footprint of the 9m by 3m interior and the outdoors that lay beyond.

Drawing was a tool by which to spend time inside. To dwell within. To draw the architectural biographies of these six women into the future of the short-term dwelling for an artist with a child. To flatten, abstract and colour, to undermine, ignore and overlay learned traditions of walls and windows. To expand beds to the size of rooms, for tables to rise and fall, for walls to concertina and dissolve. To force the existing warmth of wood and coolness of steel, whipping wind, dolloping rain, blistering sun, and tickling midges to be translated by the recollections of these six women.

‘One quick thing I would say in response to all the questions is that it is constantly changing, in that a baby / child’s needs are always evolving and you need to be responsive to that. It changes quickly too. You can find a way of working that works for you both and then suddenly your baby develops, such as starts walking and you have to reassess everything again.’

closed, open, empty, empty, open, wide

Angharad Davies is an artist and architectural researcher, who writes for public works and recently led her first build for Walworth Garden, London. www.angharad-davies.com

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.

Notes

- Interview participants were all in their thirties and are White European. Their educational backgrounds range from completed secondary education to post graduate degrees. Support varies: four live with partners, others have greater support of family members (and therefore other domestic architectures), while one lives alone with their child away from family support.

- Prioritising accounts by occupants echoed past practices of listening and recording found within feminist architecture, specifically in the work of the design collective Matrix in the 1980s. Benedicte Foo’s approach thirty-five years earlier is almost identical to ours. In her essay featured in Making Space: Women and the man made environment and entitled ‘House and home’ she interviews six women about the architectures in which they are raising their children.

– Celia Scott