On Pristine Boxes and Primeval Huts

Along with his Do Hit Chair (2000), a pristine stainless steel box measuring 1000 x 700 x 750 mm, Dutch-born designer Marijn van der Poll supplies a sledgehammer. In an act of brute physical force he requires the user to expressively sculpt his own seating morphology, not only allowing but requiring the raw and bespoke as the only possible seating experience. There is neither a drawing, nor sketch, nor plan, nor shop drawing.

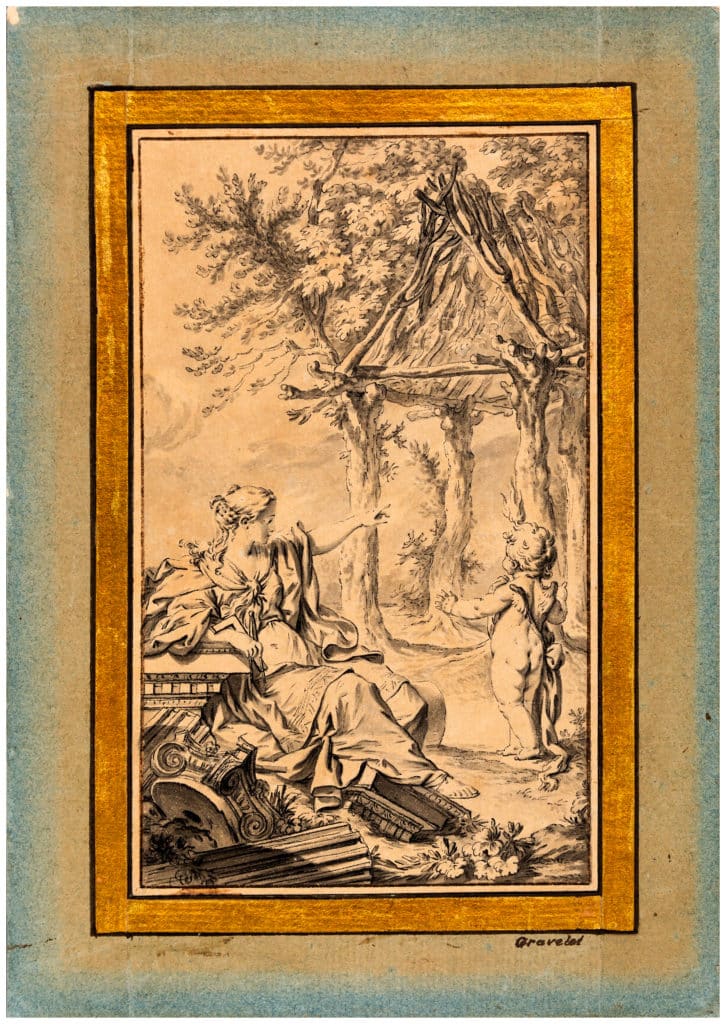

While challenging connotations and fashions of perfection in the fabrication of computational design and architecture, van der Poll reassigns the moment in which creative production may take place – there simply is no default, no standard solution, only individual customisation in pounding adaptation. In that, his piece also gives an insightful comment on a contemporary fascination to apply tools towards control and optimization in building and planning – and poses the question how and where the profession ended up, some hundred years after it was most simply and famously rendered as man’s primeval response to his surroundings in Eisen’s Frontispiece to Marc-Antoine Laugier’s Essai sur l’Architecture (1755).

In an attempt to link the two of them, the box and the hut, both can be seen as a spontaneous and dynamic emergence of form. They reveal an interest in appropriation, be it of hammers or of trees, which relates to the antagonism of Werkzeug and Denkzeug, of a device for making and a device for thinking, as it was proposed by design educators Hannah Groninger and Thomas H. Schmitz. While the former appears to be structurally complex, yet intuitive to handle rather automated tasks (such as a jigsaw), as a means to an end, so to say, the latter is its opposite: open and inspiring in form, yet requiring experience and skill to be used with profit towards unexpected results (such as a pen).

That being said, designing, drawing and making can be conceived as maybe not so much about the question of which tools we use, but rather our choice in directing, determining and defining them with and through our employment to begin with. And arguably then, it is especially in instances of unplanned creative applications towards unexpected purposes, eventually deconstructing their programming, when Werkzeuge are rendered innovative in their transforming to Denkzeuge – when we take up a critical stance, if you will.

Frank Bauer runs a Berlin-based planning agency for computational art manufacturing and works as an architectural researcher at the cluster »Matters of Activity«.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.