BOLLES+WILSON: Sketching-Over Albania

Having devoted a number of years to techniques and images engendered by holding a wood encased rod of graphite, I some years ago experienced a sort of premature redundancy, noticing that those about me husbanding architecture were now mysteriously clutching not a pencil but a mouse. I had already technologically upgraded by abandoning the wooden pencil in favour of a metal clutch pencil. These, loaded with a 6H lead, draw a paper-incising line of extreme precision. One can also reload the clutch mechanism with a super soft 6B – just the right loose-fit weapon to sketch over those super-fine, millimetre-precise printouts young assistants are apt to put in front of me.

In the days when face-to-face encounters with students were still possible, this ‘sketching-over’ technique was also an essential moment in the teaching process. A corrective line is worth a thousand words. (I now find myself running workshops for students on the other side of the globe about Venice, the romantic atmosphere of which they have never experienced first hand).

What does a dinosaur do? Look for a safe haven until the digital storm blows over? (Is it already reaching its Rococo of freakish form, and might we by now be a little bored with developer ‘bling’ and ‘eye-candy’?). Drawing Matter is certainly the most prominent safe-haven of the hand drawn. But I would like here to expound on my ‘drawing-over’ experiences in Albania – a whole country (for me at least) that has become a safe-haven of the hand-drawn.

Where is Albania? Between Greece and Italy. It was always there in stealth format, unvisitable during the years of communism. It emerged in the early 1990s, and shortly thereafter artist-mayor Edi Rama invited three international offices for a masterplan competition in the capital Tirana. Unsuccessful, we were called back by the mayor, whose polychrome façade programme was then resonating in the international media. He asked us to tutor/mentor local architects whose designs fell short of his expectations. The first of these ‘sketchings-over’ was for a tower where crazy cantilevers, echoing international modes, refused to gel into a coherent whole.

Our sketch (fig. 1) marshalled these with a coat of many colours (sun louvers).

This was the first of a number of arranged marriages with Albanian architects – a somewhat uncomfortable form of pimping that verged on the ‘lost in translation syndrome’. A mail would arrive with a heading like ‘About the Object on Don Bosco’, this we took as project title and carefully hand drew the object, the chaotic street and re-jigged façade (fig. 2).

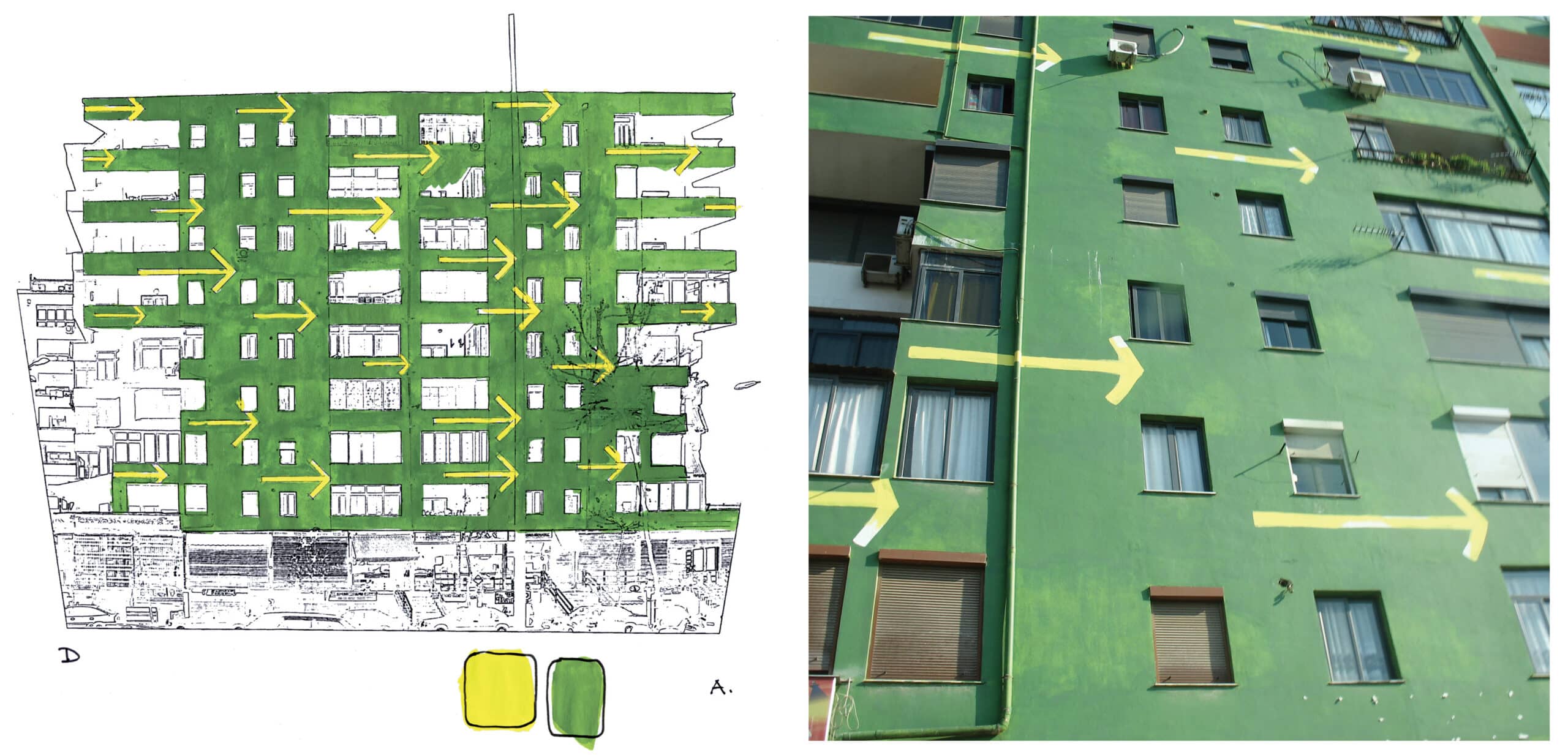

The artist-mayor (he is now Prime Minister and shows at the Marian Goodman gallery in New York) then asked for a colour scheme (fig. 3) for a large housing block (Optimistic Vectors); this appeared in the New York Times as an illustration to an article on the polychromic Tirana programme. Somewhat later, Edi the Prime Minister gave us a fast-track football stadium commission (with local hand-holders), adding 2,500 seats to an existing stadium in the northern city of Shkodra; it was needed for a ritual ersatz war between Albania and Serbia. We sketched five raked stands (fig. 4), each a coral for 500 rioting Serbians. It now, between wars, forms a peaceful pink backdrop to street life. The lobby concept of the currently under construction Tirana International Hotel also originated as a hand-drawn scenario. Obviously for a 34-floor tower the principal hand holder is a structural engineer (fig. 5).

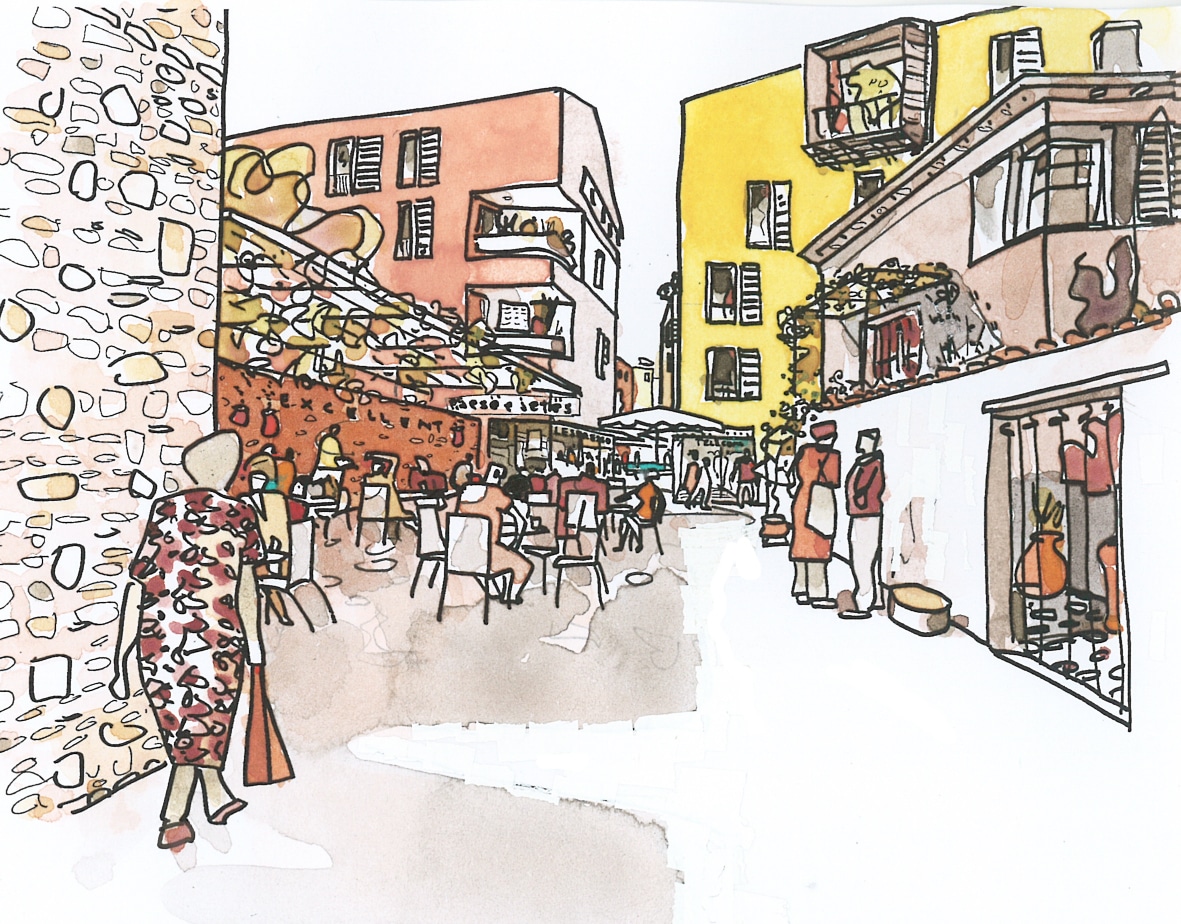

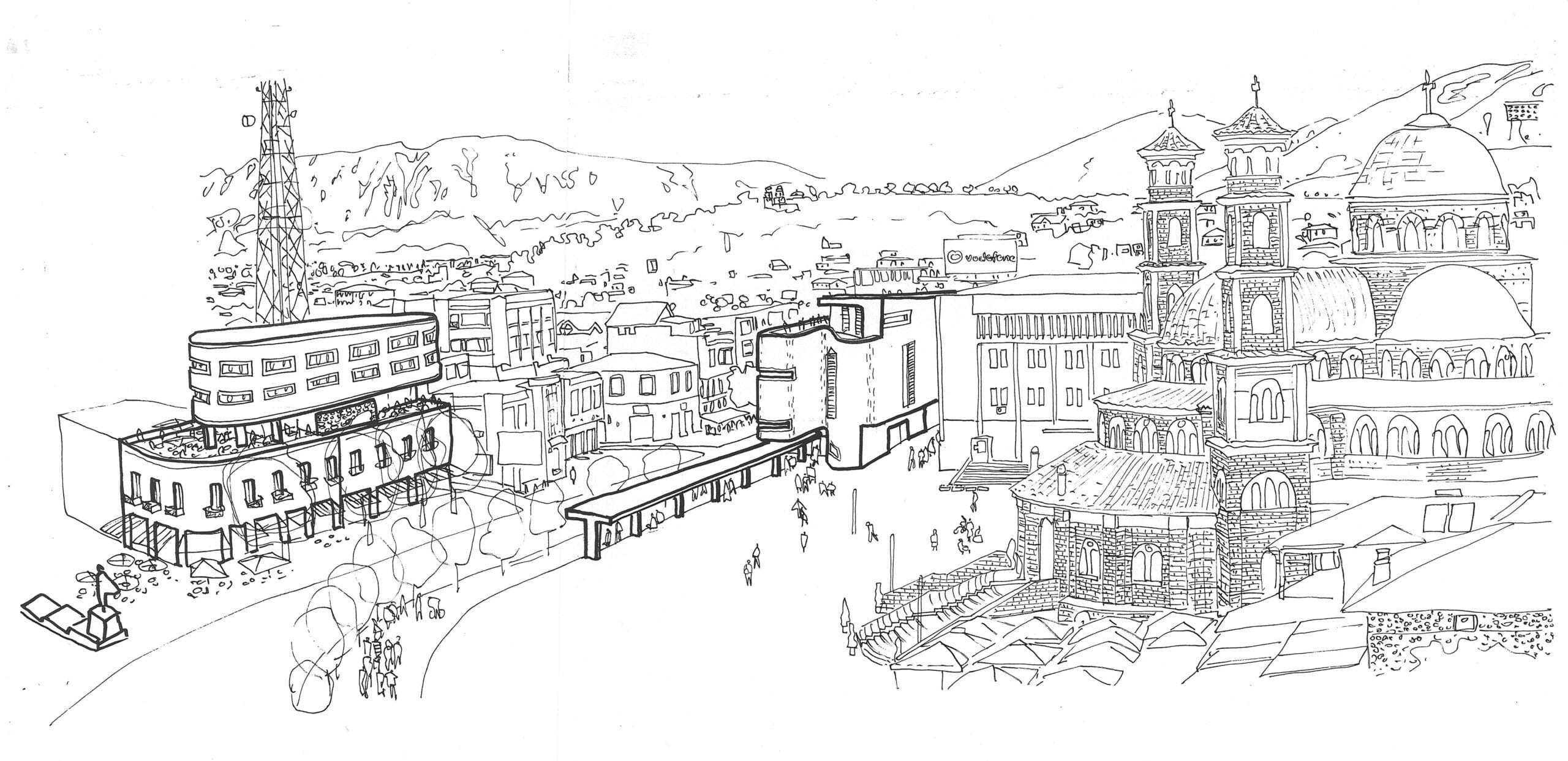

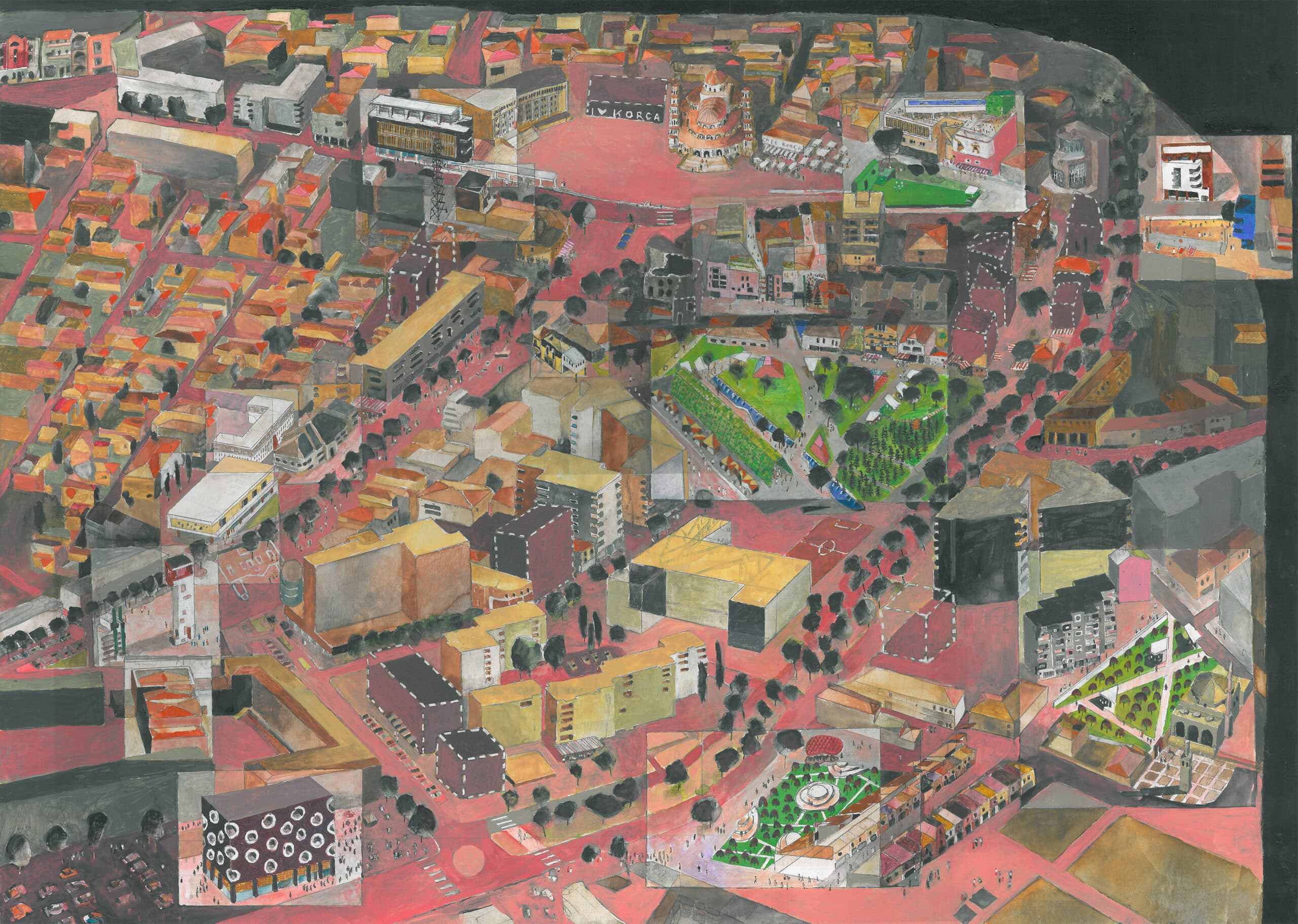

But these were only the preamble to the refinement of ‘the sketch-over technique’ in the city of Korça. Here, up in the mountains, close to the Greek and North Macedonian borders, we won a 2009 international masterplan competition for the historic city centre. Our strategy, illustrated by sketches (fig. 6), involved a symbiotic meshing of new interventions with historic stone villas. It has taken ten years for this strategy to take root, but now close-packed buildings on individual plots are adding up to a dense block matrix interwoven with traditional stone villas and medieval-scale passages (fig. 7). Here private investors follow my design and artistic supervision involving hand-drawings interpreted by trusted young Albanian architects. For each hand-drawn set of plans we get back a wad of renderings to be sketched over with further iterative details. (As in many developing countries, young architects are super digitally fit, they also diligently supervise sites, reporting back for sketched updates of the design concept). It is, for me, an ideal set-up allowing a degree of spontaneous invention and control that more legal contractual relations would preclude. I now describe Korça as my playground and the one-man design procedure as my hobby.

The first ‘sketch-over’ project in Korça, the one that brought us in contact with our young chums, followed the masterplan pedestrianising of a central street, Bulevard Shen Gjergi (St. George). At one end of this we had located a large square around the Orthodox cathedral that popped-up with the fall of communism (fig. 8). As counter pole to the cathedral the pedestrian axis terminated in a new campanile (BOLLES+WILSON, Red Bar in the Sky, 2014). Here we produced digital drawings, but at the end when the city also asked for a concept for the Rinia Park to be included in the same contract, we were forced to inform them that: ‘for that fee you only get hand drawings, and we need artistic supervision.’ ‘OK’, they said, putting us in contact with our young Albanian hand-holders to whom we issued a set of notes and detail sketches (fig. 9). The result was surprising; we learnt that elaborate handwork was affordable in developing countries but not expensive high-tech equipment. The park is now the summer social hub of the city with two or three thousand people promenading every night.

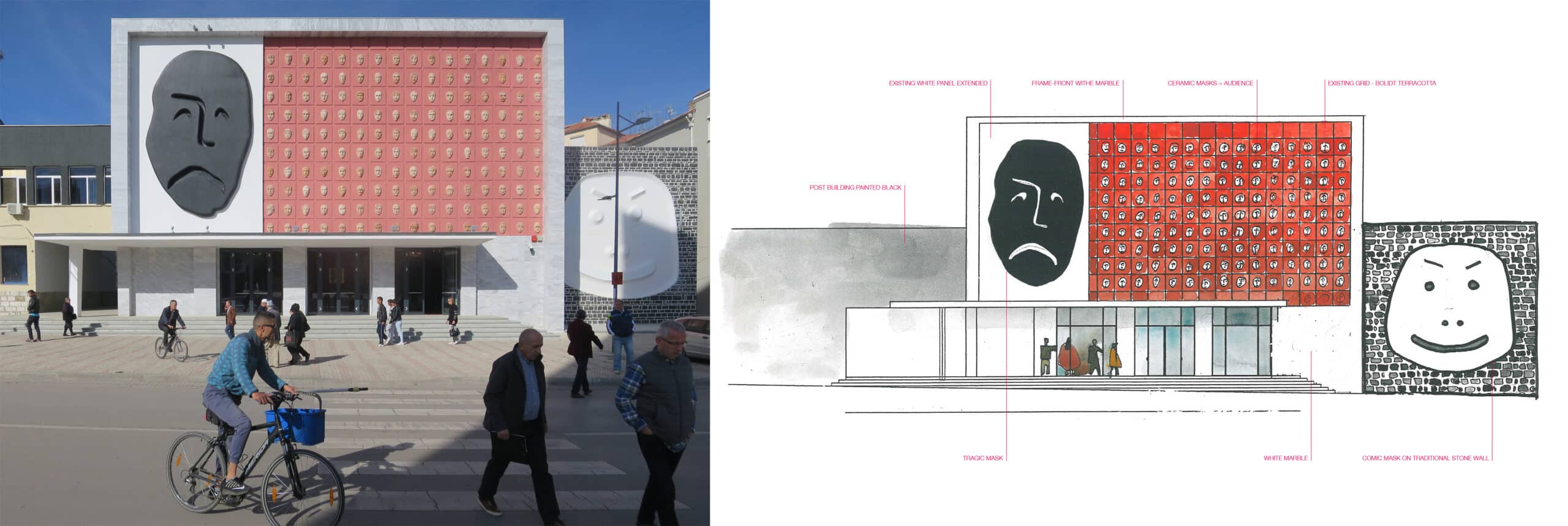

The sketching over technique progressed with our re-formatting of the communist-era theatre: the addition of a giant convex tragic mask and a concave comic mask along with 140 terracotta masks (audience) by a local potter (fig. 10). Here, on a site visit, the perplexed builders asked how to bring one corner of the auditorium to conclusion. ‘Where are the details?’, one asked, to which they produced a wad of renderings from the facilitating Tirana-based commercial office, complete with ballerinas on stage but no details. My artistic supervision role then progressed to 1:1 details hand-drawn on the wall (19th century standard practice).

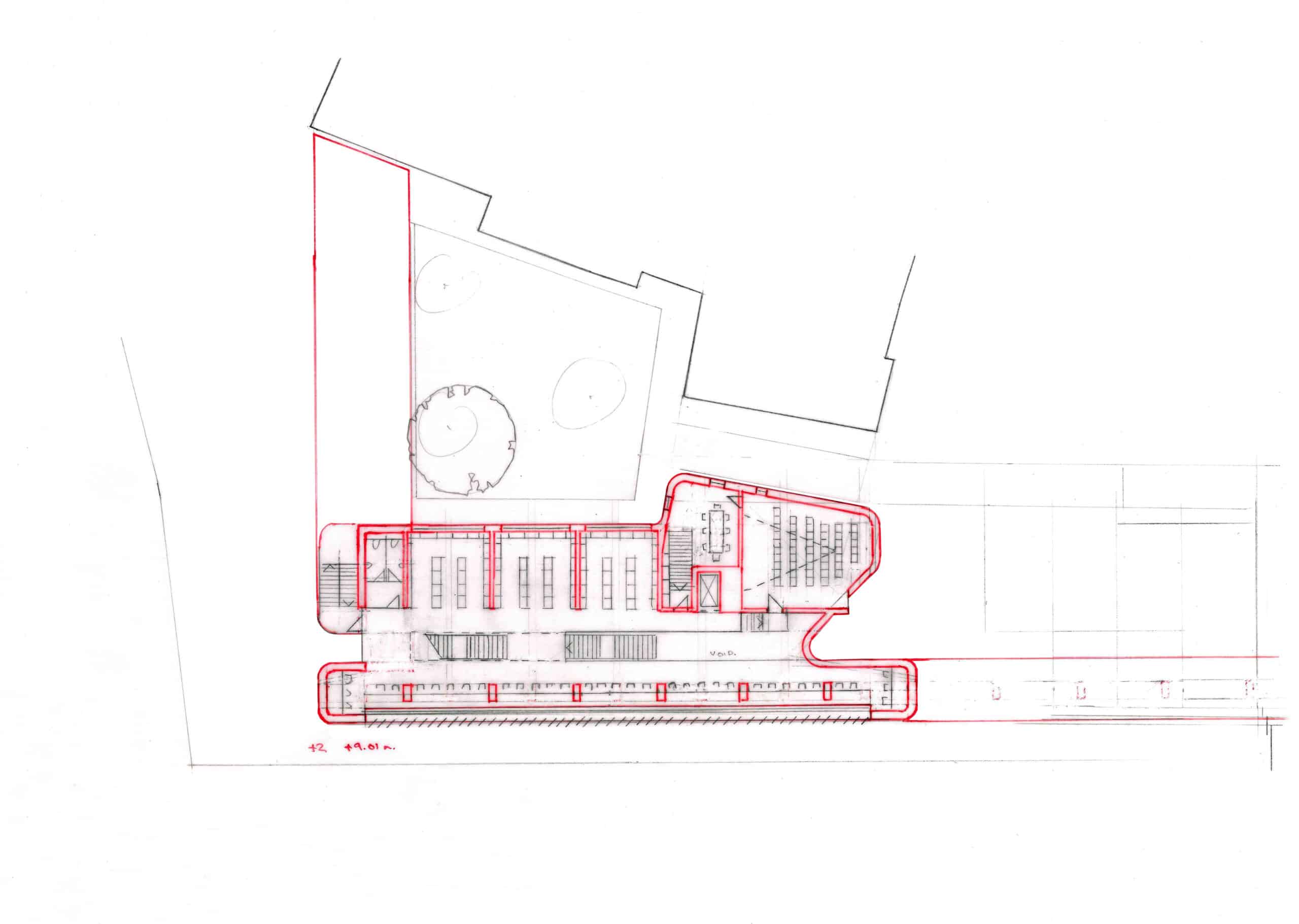

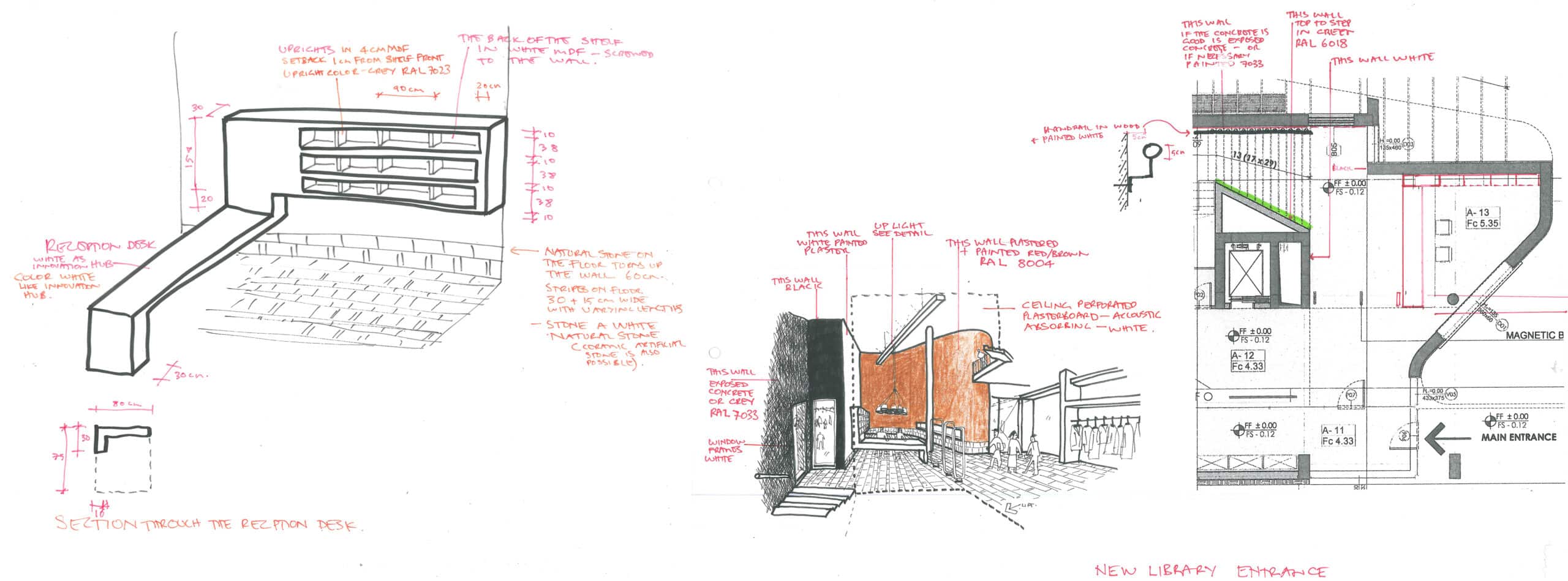

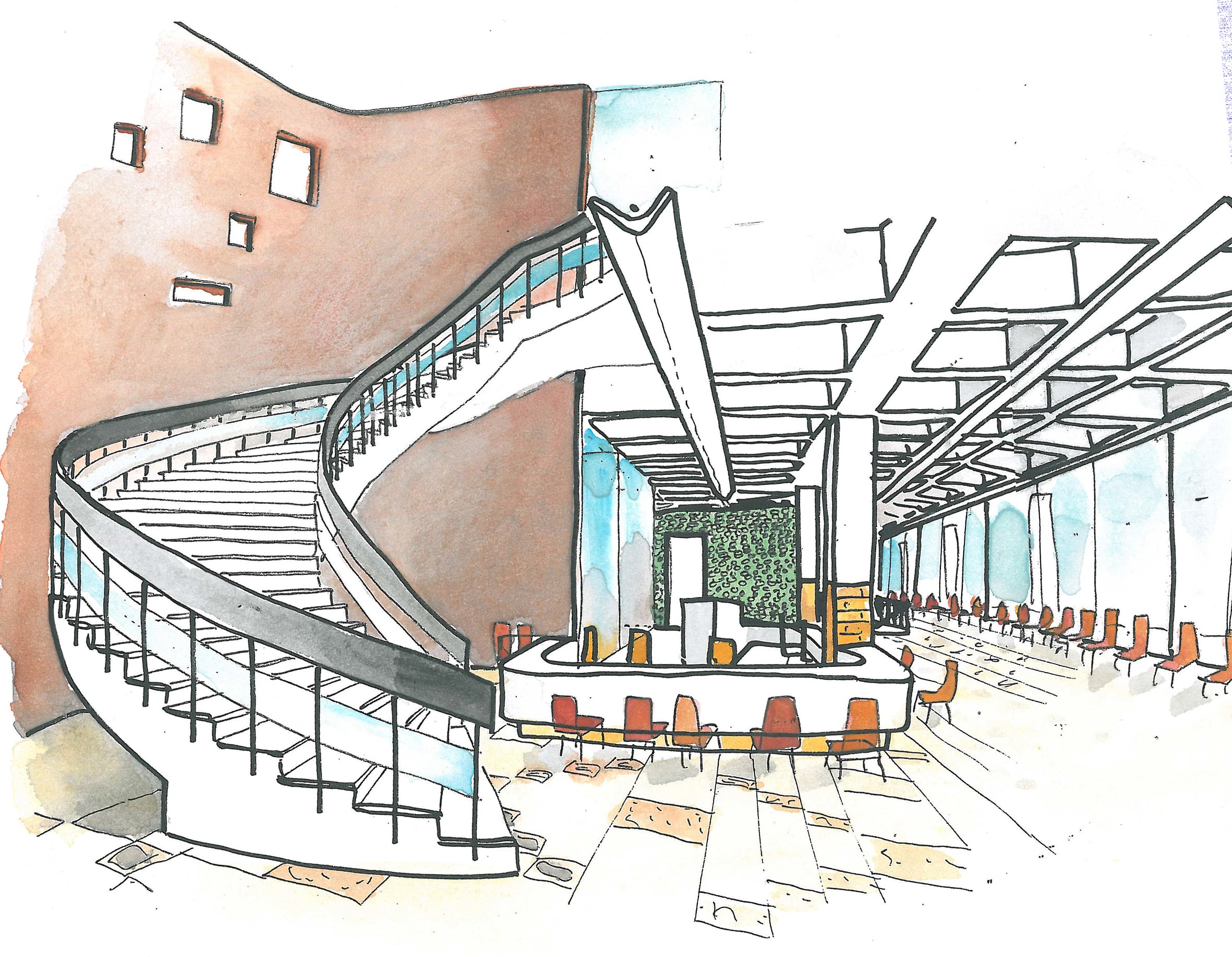

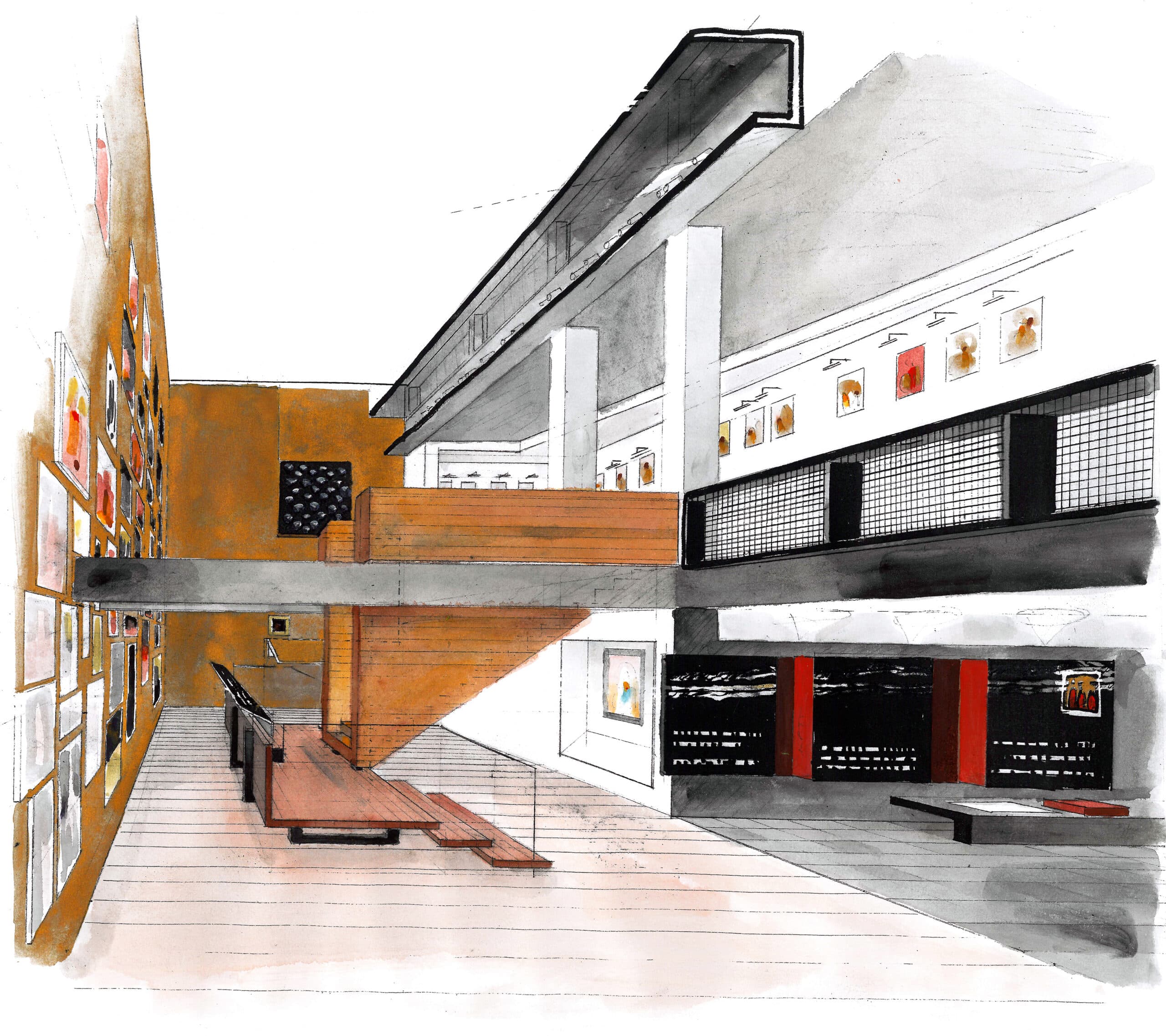

A new City Library (a theme close to our hearts at BOLLES+WILSON) is about to open in Korça. Here not only initial plans but also all bookshelf and material articulation evolved from the sketch+note technique (figs. 11–14).

Then, the old communist library was subsequently reworked as the new city hall and citizens advice office (figs. 15–17).

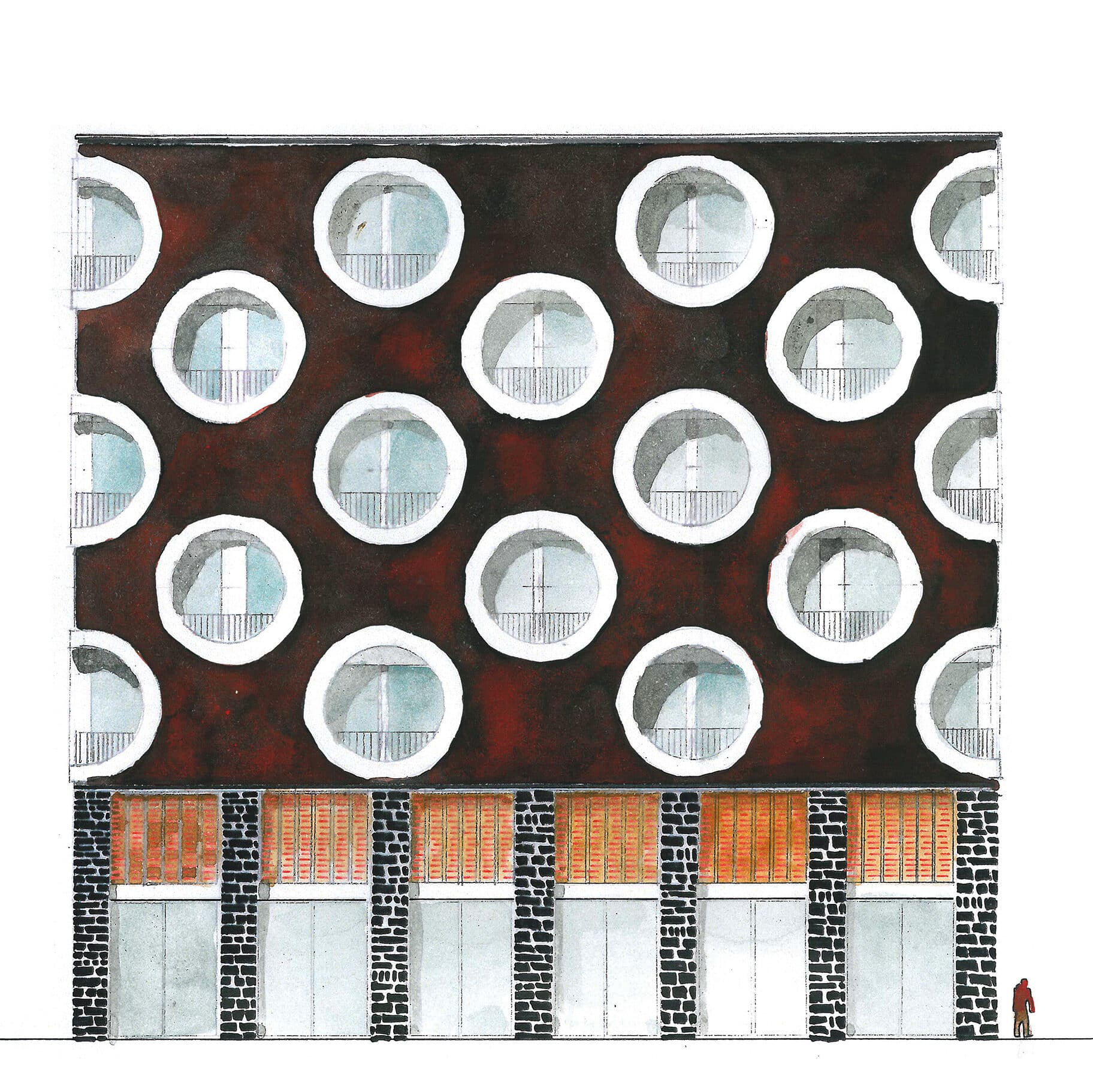

Around the corner, the new Palazzo Romeo (client’s name) is taking shape according to its sketched origin (figs. 18–20).

The full Korça story (some 30 built interventions and public spaces) is too encyclopaedic to list in full, although the 2016 Museum of Icons is well worth a visit. It goes without saying that it was engendered from the hand-drawn; the entire sequential choreography that unfolds from the gold salon whose walls are close-packed with icon biscuits (fig. 21 and 22).

At a recent Bartlett lecture a student asked at the end: ‘is it not too much?’. For Korça, not yet: they are now the role-model for city development in Albania. And I have come to terms with my dinosaur status through the validation of the hand-drawn as a form of alternative practice, not without a certain social relevance.

The full story of BOLLES+WILSON’s involvement in Albania can be found in the book: Some Reasons for Travelling to Albania by Peter Wilson.