Folding Landscapes: The Maps of Tim Robinson

While walking the land, I am the pen on the paper; while drawing this map, my pen is myself walking the land. I wanted to short circuit the polarities of objectivity and subjectivity, and try keep faith with reality. – Robinson

We should maintain an awareness of the stories hidden about us. The measurement and markings of our surroundings exist as a palimpsest of past events; rituals, relationships and livelihoods each tracing their path in the physical world. When reminded to look closely we can see how the land contains its stories ‘like the lines of a hand’ as Calvino so eloquently wrote. In our current systems of globalisation and virtuality, localising ourselves in the physical reality can be a source of comfort and dignity. It can humble and ground us, reminding us of our small place in this continuum.

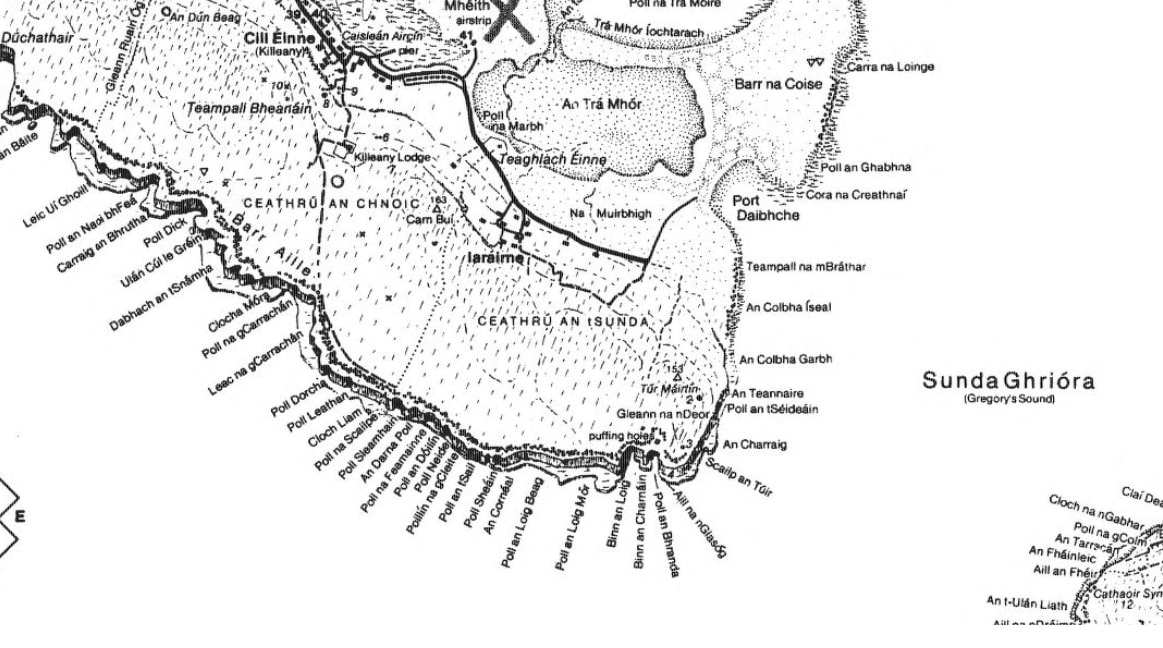

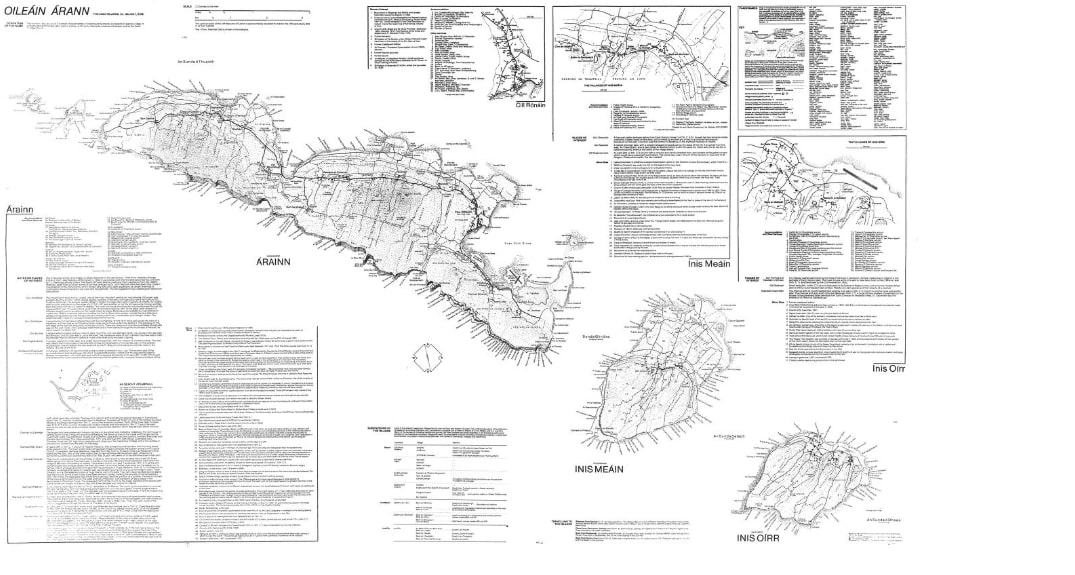

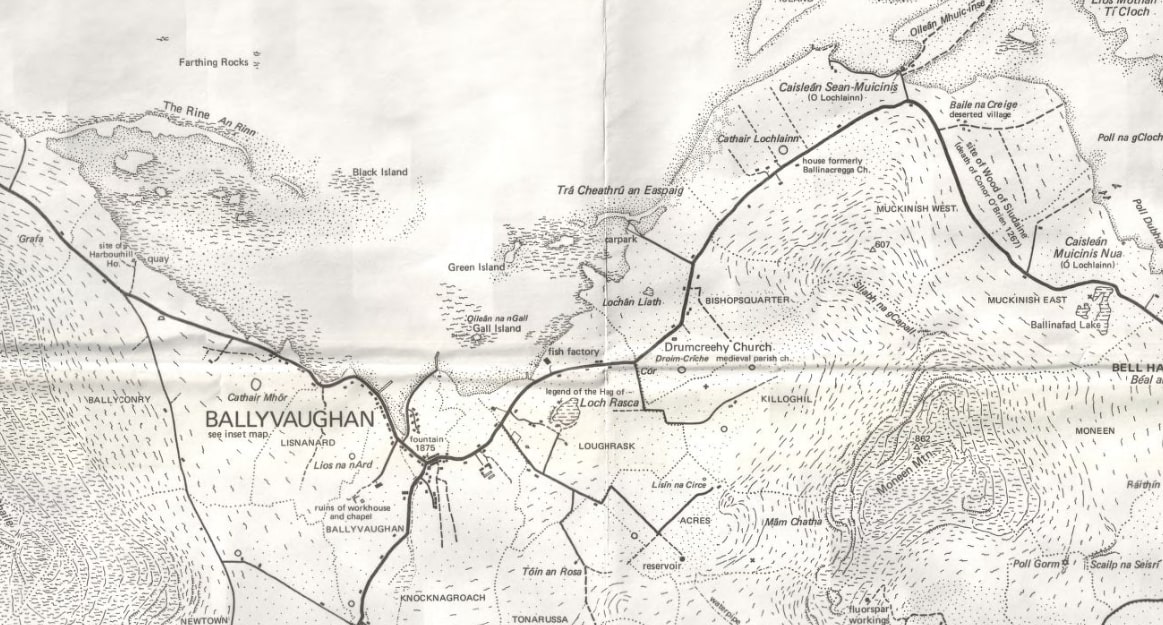

To me the drawings of Tim Robinson are a radical poetry about the importance of place. They contest the generalisation in mass-productions which separate our emotions from the world around us. Each large ink-on-paper study exists as a careful record of a specific piece of ground and so claims its importance. The pieces he chose were harsh and beautiful; The Aran Islands, at a scale of 2.2 inches to the mile, Burren at 1.8 inches to the mile and Connemara at one inch to a mile. These maps have changed the psychological experience of the place for locals and visitors alike. They heighten our awareness of history and give a deeper understanding into the complex traces of life on a storied terrain.

On moving to the West of Ireland in 1972, Robinson fell in love with the intense beauty that he discovered there. A weighty disconnection, however, was to be found between lived experience and the descriptions recorded of it. The maps of the area were bland and inaccurate. They had been made carelessly with crudely translated placenames, blurring and forgetting the richness in the landscape. He began to explore and record his surroundings closely; walking on foot, drawing by hand. Through looking carefully and taking the time to talk to people, the area was recorded from a first hand lived experience. He would wander the countryside foraging information to add, layer upon layer, atop an Ordnance Survey map made a century before. This became not only the record of a place but indirectly a record of a long process of appreciation. It required hunkering in amongst the dry stone walls, clambering over fences and stopping in for a cuppa on the way home.

Maps have so often omitted the stories of quiet lives. The cartographer controls what is important and what is to be overlooked. Authors become authorities of information and their drawings are held as a utensil of power. Describing from above, their downward looking splay holds up the observer to see as a God. Where locals can see heritage, community rituals and hard fought battles, visitors will often see empty plots awaiting development. Robinson’s drawings democratically took the landscape back for the appreciation of the ordinary people. They were made to be held in the hand; entire landscapes captured to fold up and fit in your rucksack.

I came to it from a fine arts background and used it as an art form. I wasn’t remotely interested in what the standard way of representing limestone was, for example. I was much more interested in using some sort of graphic texture on a map that would represent my own experience of the place.

– Robinson

Thousands of tiny hand drawn black marks layer into dense textures stretching over large pieces of white paper. Each page is full. Open boxes of notes allow the viewer to sense the sea running clear through them. The translations, points of interest and travel options are placed to square the space between irregular coastline and rectangular paper. The font, line-weight and ornamentation are chosen carefully to work together and come to your eye’s attention at just the right moment. The tracks and trails, the name of each monument and bay, individually marked and distinguished on close inspection, merge into a light grain when viewed all at once. This stoney grain allows us to feel present in that karst place. Robinson spoke of whiteness as the ignorance of unknowing and each black mark added was something learned.

The maps are as valuable for their extensive detail as for their artistry. The character gives an expression of a written landscape. Each is an encyclopaedic novel spread over a single page, easily flowing from abstract notation to figurative description and from two dimensions to three. This is particularly beautiful in the axonometric elaboration of the cliffs of Inis Mór. It allows the work to be dually descriptive, the record of the place alluding to its beauty. The place becomes alive when scanning your eyes across it; you can feel the salty sting of sea-air, the carved planes of rocky glacial ground under your feet.

The thousands of Irish placenames are an important feature in these maps. John Montague’s line ‘The whole landscape a manuscript/ We had lost the skill to read’ speaks of Anglicised placenames, a remnant of British power in Ireland, and how they detach the Irish people from their dinnseanchas or lore of place. Robinson, who was born and raised in Yorkshire, learned his Gaeilge from the locals in order to properly convey these meanings. He called it ‘a small act of reparation’. The correct placenames which he salvaged in roadside conversations reveal an oral topography that is full of colourful folklore telling of the area; Muiceanach Idir Dha Shaile translates as the pigshaped hill between two seas. Fo na Slanntrai, the cove of the scales, he says ‘came from the mica schist rock of which it is formed, and which shines like silvery fish scales when newly broken by waves’. Uraid, so the locals said, was to be the place where the last battle for Christianity will be fought, when the forces of evil will be defeated.

The extent of the detail present is a testament to the effort invested in its gathering. With your eyes close to the paper you will find lost monuments hidden in thickets of blackthorn, fences and drains, little improvised quays, stone-pile walls and old forgotten relics. Seeing the delicate marks of a hand-held pen on paper creates a tangible landscape of information. The act of walking and recording closely has invested them with a close connection to the earthy nature of the land. They remind us of the similarity between the maps and landscapes, both are physical evidence of human life. Now that he has looked closely and recorded, those that appreciate the area after him can see with his wealth of information and be reminded of the deep material value that the land holds.

Robinson also wrote several books about these areas, further detailing their rich culture, botany, geology and history. From his house in Roundstone, Connemara, he and his wife Máiréad published his many important works of cartography and literature under the name Folding Landscapes. They exist now as monuments to the value in a sense of place.

Declan Quirke is an Irish architecture student. He is currently studying a Masters degree at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.