Unpeopled Places

This text is the third in a series by artist Deanna Petherbridge in which she comments on a number of her recent pen and ink drawings. The drawings use imagined architectural imagery as a metaphorical means to deal with complex subject matter about social and political issues. Read the introduction to the series, here.

Some years ago, I wrote ironically about the ‘impossibility of landscape’. I concluded that landscape was dead as an artistic genre in the twenty-first century except for encounters with environmental destruction, but I was still committed to drawings of places and spaces that indicated how people live and have lived in them. I concluded: ‘My drawings are, I think, about the impossibility of drawing landscape and also about attachment to and social critique of place.’ [1]

Architectural drawing is equally concerned with place, as patently no structure exists theoretically or in actuality apart from its site. Site, place and locale are exchangeable synonyms although there doesn’t appear to be an extensive architectural bibliography arguing for categorisation. To the extent that architectural drawing is a diagrammatic form of suppositional but positivist presentation that is only peripherally involved with representation, site as the locus of transformation readily becomes subsumed into the dynamics of design.

There is, however, a huge literature on the differences between landscape as an artistic genre concerned with representation, and wider notions of space, place, mapping and environment in art theory as well as related fields of cultural geography, sociology and urban studies. The term ‘landscape’ itself as an extended concept embraces topography, social, sacralised, industrial and poetic landscapes, landscape phenomenology and semiotics, and so on, [2] and is open to metaphorical appropriation: we talk about ‘moral landscapes’, ‘learning landscapes’, ‘literary landscapes’, ‘digital landscapes’ … not to mention ‘landscape architecture’!

The imperilling of our environment through global warming and radical changes in temperature and weather patterns has, of course, called for architectural interventions in futurist design projects as well as a concentration on apocalyptic environmental imagery submitted for drawing competitions. The collaborative architectural team Design Earth partnered by Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy, exhibited the project ‘The Planet after Geoengineering’ in this year’s Venice Architectural Biennale ‘How will we live together?’. Ghosn founded the journal New Geographies and the exhibited images of four projects, ‘Geostories’ at the Cooper Union in New York in 2017 on the practice website, are described as ‘geographic fictions’. ‘The architectural drawing becomes instrumental to reckon with the cognitive and affective dissonance of climate change.’ [3] The renderings displayed in these projects – albeit only viewed online – do not reveal emotive content to my eyes; but then the robust optimism of architectural practice rests on the profound belief that problem-solving designs offer practical solutions, even when the briefs are totally conceptual. By contrast, the images of the Chinese artist Yang Yongliang, who combines the pictorial tradition of shanshui (landscape art) with contemporary digital and photographic techniques, offers a pessimistic but arresting vision of despoilation. His elaborate composite prints move between utopia and dystopia, contemporaneity and history, adding mood and affect to the mechanistic basis of the elaborate processes of their assembly. [4]

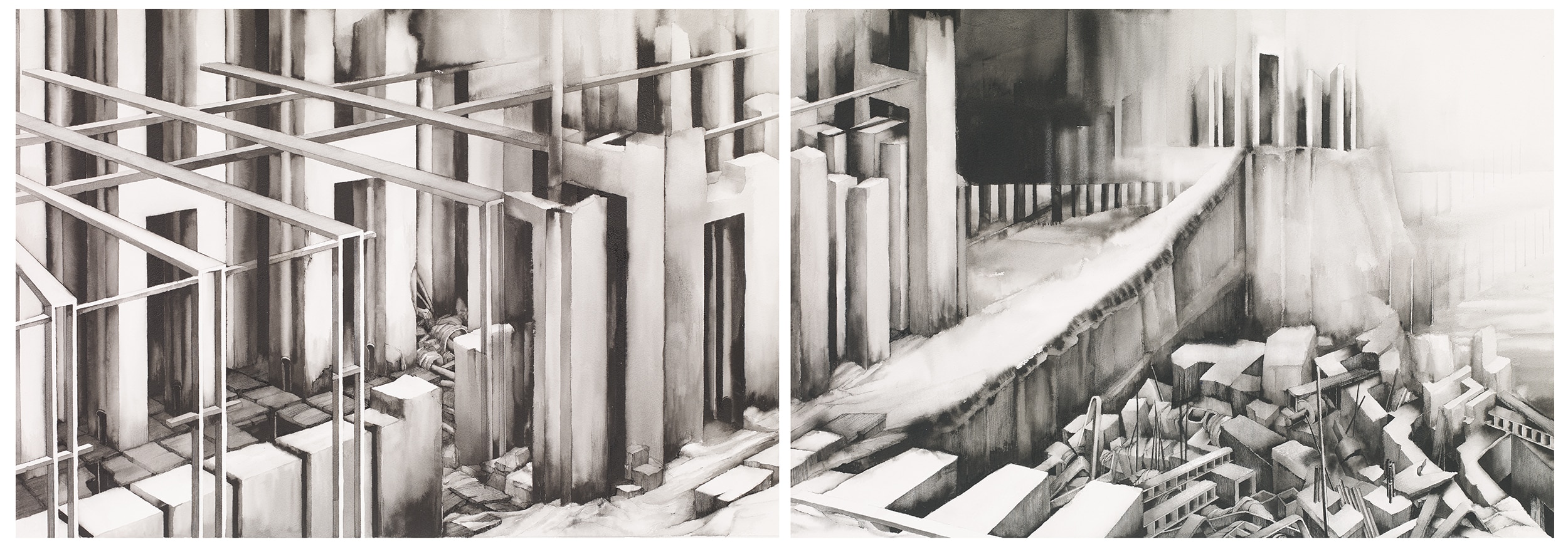

I was not speculating about any of these issues when I came to draw Utopia Contemporanea? (a deliberately pig-Latin title) [5] but rather wondering what false rhetorics could be spun by power elites and manipulated and manipulating media about rebuilding the destroyed towns and villages of countries decimated by wars and bad government. In my drawing, the juxtaposition of a misty indication of a hill-top ‘utopia’ above a valley full of building rubble in the right-hand panel was related to the partially damaged pseudo-architecture of the settlement in the left-hand panel. The elongated proportions of the openings in these imagined structures (probably whitewashed stone or mud buildings) that are neither doors nor windows lack the presence of people in the drawing to suggest human scale, usage or occupation. Significantly, the rubble and detritus of domicide and urbicide occurs in many scales and at all levels of destruction.

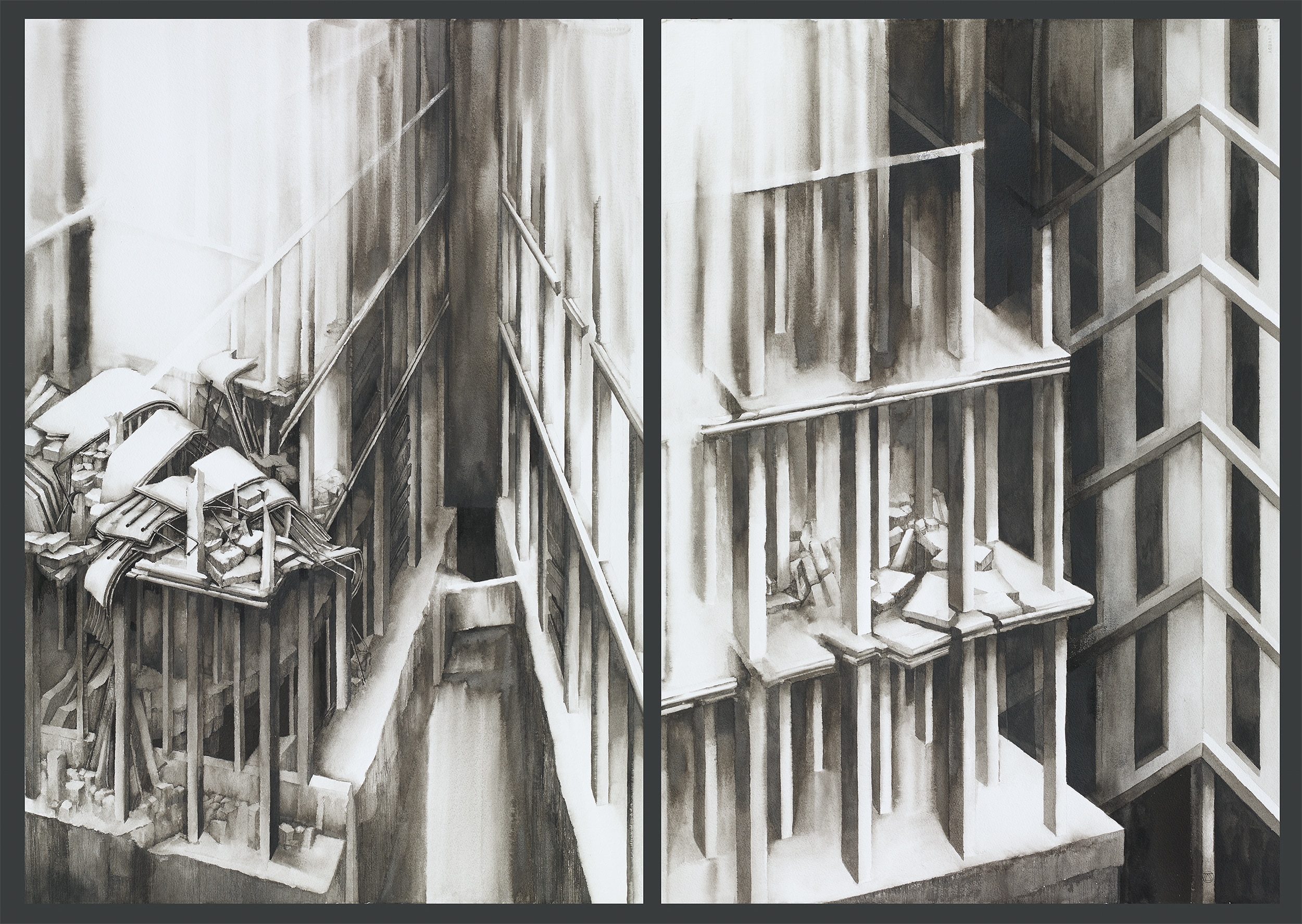

The imagined barren and rocky setting of an inappropriate rural utopia followed my diptych City on the Edge of the Abyss (2019), which transposed the political and geographical insecurities of the effects of Brexit into the city. [6] Some form of cataclysm threatens the skeletal building in the left-hand panel, and I attempted to use light as a destructive force that both illuminates empty spaces and blasts structures into glaring oblivion. It is not clear from where or how the large-scale and perversely detailed rubble in the left-hand panel has collapsed, whereas the opening chasm in the dark basement area and its shadowy detritus were imagined as being undermined by the rushing underground waters of the abyss. The right-hand panel depicts the dreary repetitive high-rise office blocks of city-centres, masking the more obvious threat of panel 1. No people are depicted.

There are no figures in any of my recent drawings which deal with allusive imagery although they sometimes appeared in earlier large-scale works that I labelled as parables. In the catalogue of the 1990 exhibition Themata, feminist art historian Katy Deepwell wrote that:

figurative imagery represents a […] development of long-standing aesthetic and political interests. The creation of meaning, atmosphere and emotion through dramatic and fantastic spaces [is] reconstructed from architectural details coupled with a multi-layering of allusions and perspectives. [7]

The awkward figures that appeared within a series of works in this exhibition dealing with political subjects were heavily stylised, partially geometric and planar in a mode, that – according to commentators – recalled the figuration of Wyndham Lewis or Christopher R.W. Nevinson. [8] I had unconsciously accessed early twentieth century ‘modernist’ language that pulled figuration towards the generalisations of abstraction and cubism in order to avoid sentimentality. I believed this bound the figures more readily into their architectural settings and allowed formal integration. In the months following this touring exhibition after pondering critical comments and my own uneasy assessment of some drawings, I realised that although the formal reworkings of such models seemed to suit my architectonic framework, the pro-war and patriarchal ideology of movements such as Futurism and Vorticism were anathema to my beliefs and compromised the work at an unacceptable level. [9] Since then, I have avoided human presences in my drawings, hoping to compensate for their absence by metaphorical associations and inflections of line and compositional and perspectival strategies.

Figuration is not only more ideologically challenged than other visual genres, it resides, inexorably, in topicality. All representations of human figures, whether in art works or adorning architectural perspectives and presentation drawings, reveal the period of their making, and are redolent with contemporary allusions. One only has to look at the fashionable cut-out or paste-in figures of architectural practice drawings to make an immediate assessment of when they were designed; just as the fashions of clothes, drapery or hairstyles or the shaping of bodies, gait and gestures plus the formal and compositional means inform us about the period in which figurative artworks were conceived and executed. [10]

I suspect that the ‘peopling’ of architectural presentation drawings as afterthought or pandering to client’s expectations, reveals significant issues about the architect’s approach to or lack of interest in usage, social conditions and the psychological impact of design. Historically in European art of the seventeenth and eighteenth, figures as staffage were often included in landscape paintings by specialist assistants rather than the lead artist – just as they were in architectural renderings. In the case of the great French landscapist Claude Lorrain, for example, these incidental figures dressed in classical or biblical garb bestowed the status of ‘history painting’ on his lush Italianate sunsets and dawn views which could now be grandly named Landscape with Dido and Aneas or Landscape with Psyche outside the Palace of Cupid.

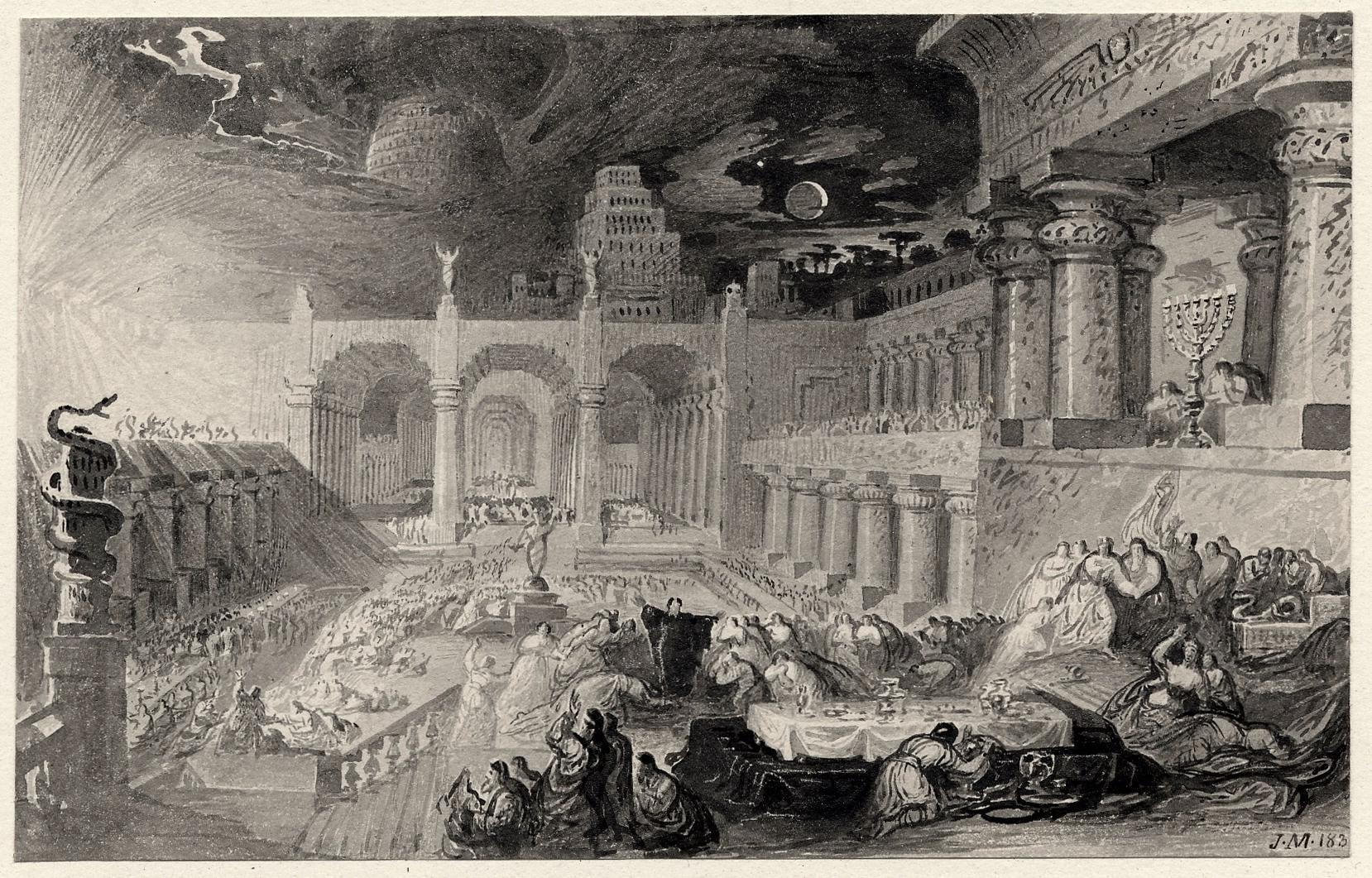

The commercially adventurous British artist John Martin (1789-1854) who toured dioramas of his huge canvases of apocalyptic landscapes to great popular acclaim in the nineteenth century, made his name with Old Testament subjects such as Belshazzar’s Feast, The Last Judgement, The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, The Deluge. Whereas the melodramatic, populist and cinematic bombast of his imagery is very pertinent to our present preoccupations with actual global meltdown, floods, fires and cataclysms, his dated and stylised figures render these works wonderfully ridiculous and bathetic. In spite of a numbered and arrowed key to the figures of the Belshazzar’s Feast painting listed in an accompanying pamphlet, Martin was criticised in his time for not following Academy rules of heroic close-ups of principal figure. [11] As an architect manqué he designed projects for a national monument to commemorate the victory of Waterloo and later in life disseminated pamphlets on civil engineering projects concerned with sewage, railway links and water supplies for the metropolis. [12]

Without the distancing – and to contemporary eyes, the alienating, manipulative and even toxic effects – of religious parables about apocalypse-as-punishment, we have to believe the stark evidence in front of our eyes about the landscapes of global warming. The parlous state of the planet, soon to be unpeopled, needs to be addressed by all of us.

Notes

- The Impossibility of Landscape’ in Gill Perry, Martin Clayton et al, Deanna Petherbridge: Drawing and Dialogue (London: Circa Press, 2016), 101. An earlier version of this essay was published in FUKT Magazine of Contemporary Drawing, no. 11, 2012.

- See the very useful summation of the field in John Wylie, Landscape, (Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2007).

- www.design-earth.org/exhibitions/geostories-cooper-union: ‘These geographic fictions render visible the unaccounted-for spaces of technological externalities – of landscapes of resource extraction and waste management – all while bringing forth some of these systems; attributes as generators of a renewed civic design. The architectural drawing becomes instrumental to reckon with the cognitive and affective dissonance of climate change, between what feels like an individual concern and the collective planetary consequences.’

- www.yangyongliang.com

- Utopia, of course is a greek word : outopos, means ‘no place’, ‘nowhere’ although we’ve added all sorts of spins in modern usage.

- See ‘Crossing the Abyss’ www.drawingmatter.org/projects/editorial/deanna-petherbridge-drawing-as-metaphor/

- Katy Deepwell, ‘Themata’, introduction to Themata: New Drawings by Deanna Petherbridge, exhibition catalogue, 18 January–16 February 1990 (London: Fischer Fine Art), 3.

- The Family of Man, Mary Approaching, Walled around by others’ vociferations and Communion, 1989.

- Many artists working in this period, such as Paul Nash, David Bomberg, William Roberts, just to name a few British artists whom I still admire, were, of course, passionately anti-fascist and anti-war. And there were a few women amongst them, including Winifred Knights.

- See commentaries by Philippa Lewis and Birkin Haward in Drawing Matter.

- First exhibited in 1821, the finished oil is now in the Paul Mellon Collection, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. It also existed as a dramatic mezzotint made by John Martin, much copied by other hands including the etching ‘Key from A Description of the Pictures of Belshazzar’s Feast, 1821’ in a pamphlet by Michael J. Campbell. It was the most famous of Martin’s single images and launched him as a popular painter of international renown.

- Lars Kokkonen’s essay in the Tate exhibition catalogue 2011 with the ironic title ‘The prophet motive? John Martin as a civil engineer’ questions previous art historical suppositions that these utilitarian projects were dictated by evangelical beliefs. See Martin Myrone, ed., John Martin Apocalypse (London: Tate Gallery 2011), 35–41.