Forced Migrations, Barriers and Vanishing Asylums

This text is the second in a series by artist Deanna Petherbridge in which she comments on a number of her recent pen and ink drawings. The drawings use imagined architectural imagery as a metaphorical means to deal with complex subject matter about social and political issues. Read the introduction to the series, here.

The Authorial not the Authoritative Narrative

Writing about one’s own work sparks the very real danger of suppressing the interplay of interpretations and readings that visual art demands of viewers. For a work to come alive it needs to be a site of mutual exploration. The worry is that an authorial text closes down responses because it is assumed to be the authoritative ‘last word’ on the subject… whereas, on the contrary, what the artist has to say is only the beginning of a free-for-all. Or what has been defined in more theoretical and pompous language as ‘the shared agency of cultural discourse.’

The influence of passing time on memory plays a large part in writing retrospectively about making an artwork. An artist’s current opinion about the quality of a work is probably the dominant factor in reshaping recollections of its development; and the remarks of viewers or subsequent readings and thoughts on the subject are also unconsciously sifted into the mix. This is all the more so in traditional two or three-dimensional pieces where the finished or public artwork is a summation of past activities and decisions from which the author is now absent. By contrast, more and more twenty first century works move towards live performance in real time with spectators witnessing a drawing or painting or art-inspired performance activity being shaped before their eyes with the artist playing a dual rôle as inventor and animateur. The desire of spectators to participate in the actions themselves, as in communal drawing workshops, for example, or immersive theatrical events is much promoted by cultural apparatchiks under the rubric of ‘relational aesthetics’. [1] These participatory desires are embedded in the powerful dominance of current identity politics in shaping cultural activities: a little like the enthusiastic football fans who rush out on to the pitch at the end of a match whenever crowd controls falter or are loosened. They are performing participation just as they previously enacted witness to the match in front of the roving camera lenses of global reportage.

After the commencement of the Syrian civil war, digital cameras and mobile phones captured the images of literally millions of displaced citizens on the road: moving, moving, moving from civil war in Syria and joining the swelling tide of migrants from Kurdish territories, from Afghanistan, Asia and Africa seeking asylum in Europe after the most hazardous of land journeys and sea crossings. Only film can capture the immensity of individual suffering in such mass movements: even photography can only freeze-frame symbolic moments, such as the image of the drowned Syrian infant Alan Kurdi, washed up on the Turkish coast near Bodrum in September 2015. Visual art has to look to its own strategies when dealing with such immense events and the proliferation of participants, in the hopes that static imagery can somehow present itself as a potent, if tangential, commentary or memorial. The artist/author needs to lay down a symbolic set of references in compensating for the lack of respect for the myriad absent individuals of these terrible subjects.

Migration: Baggage-light but laden with fears

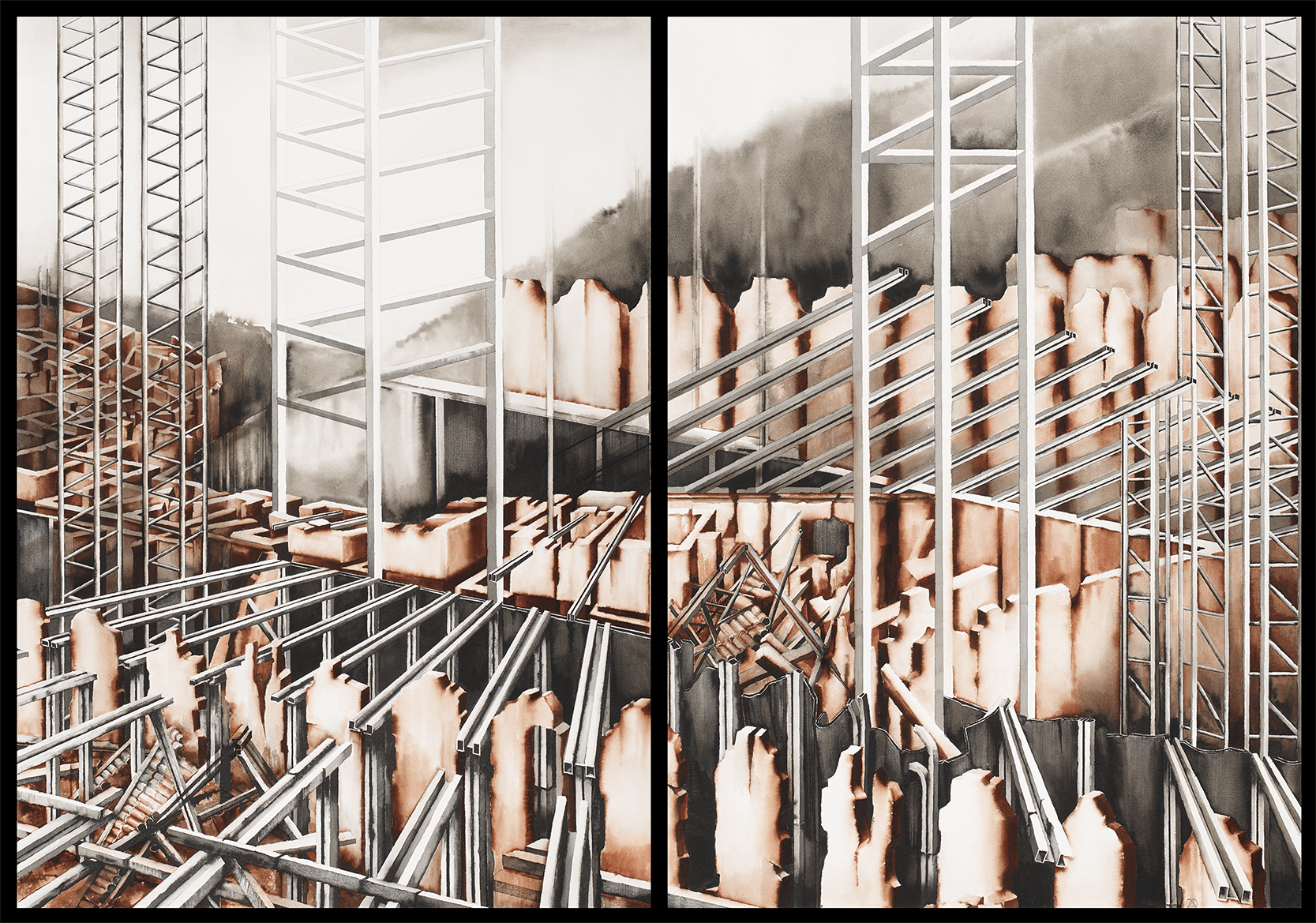

I only remember a few aspects of the making of the drawing Migration 1 (above) in 2018, after the completion of The Destruction of the City of Homs and The Destruction of Palmyra. [2] There was an early decision to work in duotone, but only when I began the drawing in the lower front area of the left-hand panel, did I realise that the warm, difficult to handle terracotta watercolour suggested third-world rammed earth structures that could readily collapse and disintegrate. What began as a series of uprights of a damaged wall began to assume the presence of a sequence of battered and slightly humanoid mud-brick tombstones with grey wash over fine ruled pen lines confined to the metallic struts of watch towers, fences and structures belonging to the cold technological world of unwelcoming ‘First World’ detention camps. These were material choices that followed from my painful reflections on the fetid, sordid and crowded camp at the end of a painful journey of migration or fenced and policed internment settlements. The Calais ‘jungle’ migrant camp; the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos facing the Turkish coast; the Australian detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea… these and other destroyed or rebuilt camps are still the unwanted destinations and places of enforced residence for many. Rather than functioning as sorting and supporting stations, they have become the hopeless prisons of unfortunate asylum seekers who desperately aspired to freedom and economic sustainability in escaping the wars, governmental tyranny or insurmountable poverty of their home countries. As I wrote in a catalogue essay in 2017: ‘If we believe that armaments and disaster rehabilitation investments are more important than foreign aid then we come up with arguments that ‘economic migrants’ are somehow illegitimate unlike those ‘real’ victims of wars (that we helped to create) but are doing very little to help resettle.’ [3]

I began the drawing with thoughts about the distant destroyed environments, the rubble and ruins from which immigrants have been displaced. Although drawing can readily suggest speed and emotion through agitated lines, in practice change, movement and the passage of time have to be flagged up in a different way from words, film or music, the time-based media. So, in this two-part drawing, the before and after of migration collided into simultaneity. The metal watchtowers, guard stations and reinforced perimeter walls of future concentration camps grew like ghosts amongst the disintegrating villages of some indeterminate origin or embarkation. And although the sea is still and the landscape hazy, I hoped that by situating the starting point of the migratory journey on the edge of a misty, watery background would somehow suggest the blank of a deeply insecure future. The contradictory directions of metal transoms spanning impossible spaces in impossible ways added dangerously to the complexity and excess of this drawing: possibly the most complex work of all my overwrought oeuvre. I was fearful that this would repel viewing but I felt hazily then (and now have rationalised it considerably in the light of subsequent events) that the subject was so complex and laden with issues that it required exorbitant detail and deliberation in the making. Today, under Covid, the spurious rhetorics surrounding immigration have themselves migrated into even more complex and dissembling narratives about pollution through the entrenchment of populist governments. In the UK, hazardous immigrations no longer spell out media stories of economic distress and political abuse even for those righteously concerned about government cutbacks on international aid, as all invaders from other places can now be readily targeted as spreaders of the coronavirus plague. The moral codes of political disasters have become enfolded within a threatening physical discourse of contagion: the concept of victimisation of innocence now equally threatens both sides of the confrontation.

Blood Crossings

I employed more obvious visual metaphors in the long triptych entitled Blood Crossings. Roads, bridges, railway lines – particularly the repetitive horizontal rhythms of railway tracks – symbolise passage, movement and direction. I organised these into exaggerated receding perspectives, which called for the horizontal usage of standard sheets of Arches paper and a third panel to produce an impression of an encircling panorama. In the foreground are curious metal platforms which I had envisaged as viewing platforms, impossibly raised above the paths and bridges for us, the invisible guards and spectators. The front of the long empty bridge on pylons traversing rivers and seas is clogged up in the third panel with crowded and immovable blocks of concrete, piled up behind barriers. These referred (in my mind at least) to the images that flooded the media from February 2018 of desperate Venezuelans crossing a narrow bridge into Columbia in their thousands to escape famine, and later painful images throughout Donald Trump’s presidency of the great march of the hungry and the desperate through South America to the borders of Mexico and the USA. Stonewalled by North America, they have turned to stone in the drawing.

The use of red wash in this work, I believe, requires no commentary.

Walls of Exclusion

I did not look at any images of the wall that Donald Trump was building along the Mexican border while making this drawing, although I have now seen how often photographers have recorded its shadows rather than its insane structures as it has been extended over varying stretches of geography. I simply wanted to suggest its repellent aridity by the precision of the drawing technique. The dominant upright supports were angled to display hollow reinforced metal terminals that could be read as iconic equivalents of a Nazi swastika. Walls contain as much as they exclude, and the chaos of distant and threatening landscapes and stony, reedy ravines were also the ‘barbaric’ forces that were breaching the walls and the carefully laid paths of this new repressive order of hysterical demagogy.

It was not only Trump of whom I was thinking while making this work. Victor Orbán had also erected fences along the border with Serbia to keep out the migrants from entering Hungary, with a second tranche completed in 2017. Such recent barriers are foreshadowed by Israel’s concrete West Bank Wall of exclusion against Palestine, the so-called Peace Walls of Belfast dividing Catholics and Protestants, the Berlin Wall, the Green Line of Cypriot partition. All the way back to Hitler’s Atlantic Wall and the partition of India and its railway-line massacres, these improbable projects of physical separation and aggression are always breached in time. While making this black and white diptych I never envisaged the present airborne pandemic that would render all solid barriers fictional… the very essence of immaterial two-dimensional drawing.

Notes

- The term was coined by Nicolas Bourriaud in the publication Esthétique relationnelle (1998) and although it has been much contested since, is still used to validate process-related art ‘taking as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space’. Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002), 14.

- https://drawingmatter.org/the-destruction-of-the-city-of-homs; https://drawingmatter.org/drawing-on-history-mirages-interventions-and-contestations

- Deanna Petherbridge: Places of Change and Destruction (London: Art Space Gallery, 2017) (unpaginated)