Drawing on History: Mirages, Interventions and Contestations

This text is the first in a series by artist Deanna Petherbridge in which she will comment on a number of her recent pen and ink drawings. The drawings use imagined architectural imagery as a metaphorical means to deal with complex subject matter about social and political issues.

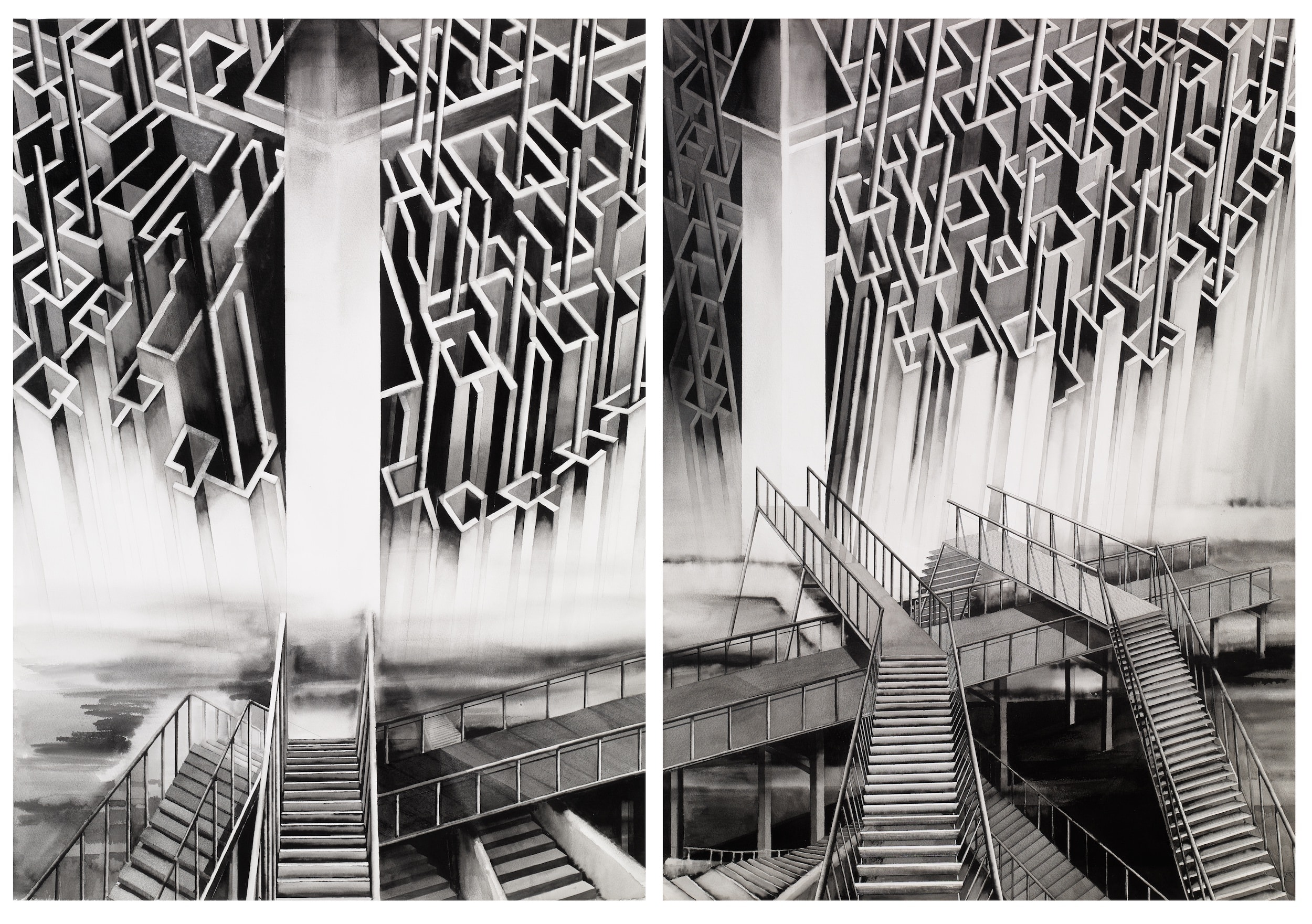

Late last year I completed my double-panelled pen and ink drawing On Shifting Sands: Viewing History, responding to the complexities of reinterpreting history, its recorded documents, and its monuments: a debate that has been so potently reinvigorated by Black Lives Matter.

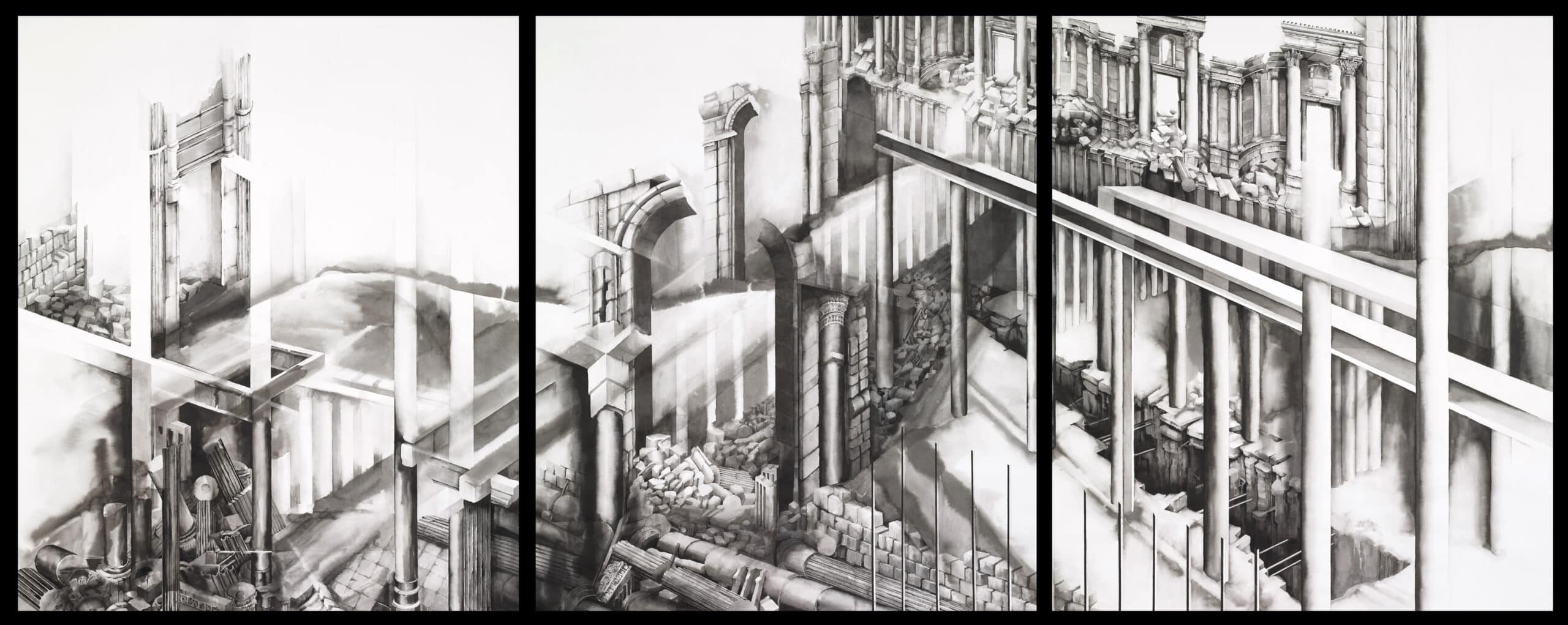

A profound unease about the historophobia of the contemporary art world – the ignorance and dismissal of the history of art by practitioners and exhibition curators, art teachers and students – has long haunted me and been the subject of lectures and articles. This is a parallel issue that I won’t pursue here, except to note that my invented term that marries history with collective exclusion is fiercely resisted by those twin computer demons, Word and Google, who either alter it or send in a destructive gremlin every time I try to initiate a discussion on screen. By contrast, Google willingly allows me to contemplate smoke and rubble-filled images of all forms of war damage, from great architectural treasures (such as the Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo, irreparably damaged on 24 April 2013) to the deliberate destruction of ancient monuments by Islamist extremists. As we’ve all witnessed, these range from the destruction of the huge rock-cut Buddhist statues of Bamiyan (northwest of Kabul) in Afghanistan by the Taliban in March 2001 – via ISIS attacks on libraries and museums in Mosul, Iraq – to the blowing up of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud on 11 April 2015, followed by the destruction of Sufi mosques in Timbuktu by local Al-Qaeda terrorists in Mali. In June 2015 members of IS/Daesh, the so-called ‘caliphate’, blew up the temples of Bel and Baalshamin in Palmyra, and brutally beheaded the archaeologist and scholar Khaled al-Asaad who was defending the museum. The site was recaptured by Russian-backed Syrian troops in 2016. After the defeat of IS/Daesh in May, Russian allies mounted a classical concert, with a close friend of Putin’s playing the cello, in the cleaned-up Roman amphitheatre (misquoted and sliding slowly downwards in my drawing). An article in The Economist dryly noted on 6 May 2016:

As the chords of the Mariinsky Theatre orchestra filled the Roman amphitheatre of Palmyra […] the music’s message was clear: there is civilisation and there is barbarism; stand with Russia on the side of the good.

When drawing the large triptych, The Destruction of Palmyra, I was beset by doubts about my legitimacy and competence to deal with such a complex and painful subject. My hesitancy was mainly triggered by the fact I had never visited the site, nor indeed Syria, although I had completed the smaller triptych, The Destruction of the City of Homs, now in the Tate, and envisaged the two works as companion pieces. [1] My compensatory mechanism was to do as much visual and textual research as possible, which led, almost unconsciously, to a drawing process of quotations and deliberate misquotations and juxtapositions of fractured spaces. [2] I re-envisioned the remains of the Temple of Bel and shattered triumphal arches; I reconstructed ghost colonnades and invented variations of capitals, columns, and entablatures on my version of the damaged late-Roman amphitheatre. These structures related vaguely to current images in the media, but also to historical photographs from the nineteenth century and stylised eighteenth-century prints. In 1751, the antiquarians Robert Wood and James Dawkins set out on an expedition to the ancient city of Palmyra (funded by Dawkins’ Jamaican sugar-plantation wealth). The published images were printed in Robert Wood’s account of this extended exploration. The visit was also memorialised in an enormous oil painting by Gavin Hamilton, held in the National Gallery of Scotland, James Dawkins and Robert Wood Discovering the Ruins of Palmyra (1758), alongside subsequent engraved reproductions. Dawkins and Wood are dressed in voluminous togas, unlike the oriental dress of the other figures approaching the ruins under exotic palm trees. Examinations of such Western cultural appropriations are well theorised and a recent revisionist essay concludes:

…not only has the preferential treatment of ‘Roman’ Tadmor-Palmyra done a disservice to the other periods of the site, but […] this myopia has contributed to narratives which weaponized the site itself as a focal point of Western memory. [3]

In the centre panel of my entirely fictional ensemble, which ignores the flatness of the vast plain of Tadmor, is a tumbling river of rubble. And emerging, improbably, from the sloping and falling-away Roman amphitheatre, is a bleak, ghostly, and modernised aqueduct structure spanning an abyss. This was a nod to future impositions or rebuildings of the site. I have learned that reconstructions are now being proposed for this troubled site, specifically from Russia, the dominant partner in the newest incarnation of transactional imperialism. [4]

Imperialism and its dubious histories of power, oppression and greed are perhaps the connecting link between these two very different drawings that aim to pictorialise the denial or reinvestigation of the past through visual metaphors.

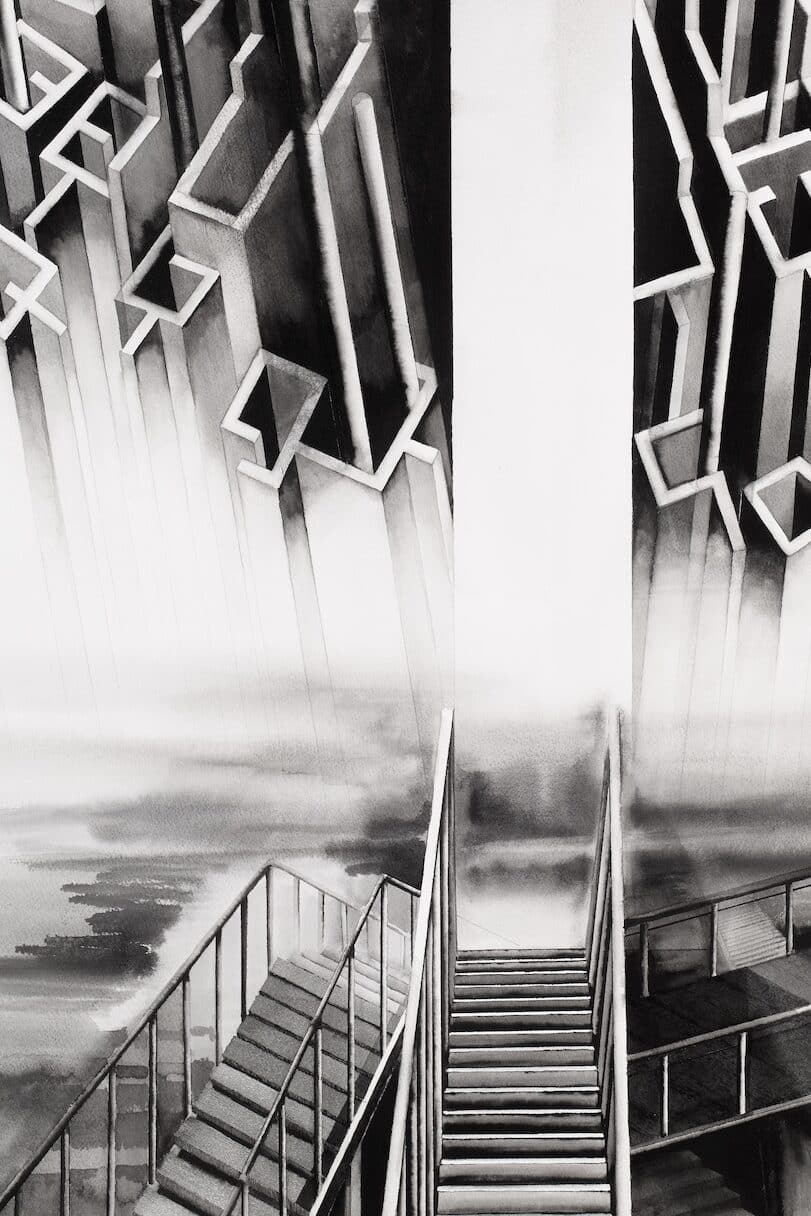

On Shifting Sands: Viewing History was not troubled by the same doubts as The Destruction of Palmyra, but grew with a sort of unexplained boldness and fluency, despite not having clearly translated the impossibly abstract strands of thinking about the issues into a visual form in my imagination. I found myself drawing bridges and over-reaching banks of stairs uneasily crossing marshy quick-sands and treacherous waters, and these soon asserted themselves as viewing platforms and open promenades in the lower part of the drawing. Later, clusters of illogical compartments forming an impenetrable maze started hovering above the empty steps and walkways. These curiously solid mirages, rather in the manner of the apocalyptic space invasion platform in the film Independence Day, separated the two panels of the diptych, united by the viewing platforms below. The deep but only occasionally connected downward-pointing walled cubicles seemed to defy the easy passage of entry and exit; although they are occasionally inhabited by simple cylindrical markers. They use a different and conflicting perspective and formal language from the seascape underneath and are reached by empty and ghostly vertical passages that connect with but never unite the worlds of the past and present.

There is a long tradition in Western religious art of dividing of panels into above and below: the spiritual or non-material plane above in which angelic creatures hover, or more aptly, demonic creatures fall from grace, and to which the mortals in the human spaces below connect with gestures and upward glances. Such iconography is often structured around contrasting perspectival systems, and although I don’t believe I was consciously making these historical connections when composing the conflicted organisation of On Shifting Sands, the thought did occur to me afterwards. All authorial descriptions of making art are post hoc; even those laboriously limited to a remembered chronology of processes and materials.

Claiming to be authorially semi-detached while actively drawing or projecting metaphors of enablement onto the processes of making might seem to be an embarrassingly romantic flight of fancy or downright sloppy thinking. They could, perhaps, be particularly challenging for architects who rely on carefully constructed briefs and logical developmental programmes before permissible intervals of invention. But in my experience, the process of making art involves variable methodologies and the need to engender new, if unconscious programmes for each project in response to the underlying subject matter, conceptual framework and the vague, half formulated images in the ‘mind’s eye’. Each new work summons up a modified visual language, comparable to pieces of music that demand a differentiated ‘sound world’: another scale (sometimes simply contrary to the scale of imagery or the spatial perspectives of the preceding oeuvre); a new vocabulary of forms and composition; and even in pen and black ink, a new chromatic range: favouring greys and mid-tones and subtle washes or intensities of contrast, light and shade. All moderated by the paper support, where texture and materiality call for open passages of white emptiness and subtle transitions or defined imagery contained by or continuing beyond the frame.

I am suggesting that, in whatever medium, all cultural output gradually enters into a relationship with the initially hesitant or dominating author to engender a form of disembodied ‘conversation’. All of us have experienced this, knowingly or not. Whether it’s responding to the initial language choices that have shaped the wording of an email or a tweet (let alone writing a poem or a work of literature), I maintain that all writers enter into a textual assessment that serves to animate the next stage of development… even whether to send it unedited or to spend a little more time structuring the message. It is in this light that I offer up a description (?) a justification (?) a parallel text (?) about two drawings that, improbably, deal with abstract thoughts about history as subject matter.

Notes

- https://drawingmatter.org/the-destruction-of-the-city-of-homs/

- I was most grateful in this respect for a studio visit from Niall Hobhouse, and his useful references and enlightening personal reminiscences. The work was displayed in Deanna Petherbridge Drawings: Places of Change and Destruction, an exhibition at the Art Space Gallery, London, 6 September – 1 October 2017. See also the RAF museum video Today’s War Ruins: http://www.deannapetherbridge.com/pages/Profile/Current_Events.html.

- J.A.Baird and Zena Kamash, “Remembering Roman Syria: Valuing Tadmor-Palmyra from ‘Discovery’ to Destruction”, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, 62–1, 2019

- Ammar Azouz, ‘Re-imaging Syria: Destructive reconstruction and the exclusive rebuilding of cities’, City Vol.24, Issue 5–6,2020. See also his forthcoming publication Domicide: The Destruction of Home in Syria, London: Bloomsbury (Autumn 2021).

– Elizabeth Hatz