Pan Scroll Zoom 18: Wolff Architects

– Fabrizio Gallanti, Heinrich Wolff and Ilze Wolff

This is the eighteenth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode, Heinrich Wolff and Ilze Wolff of Wolff Architects discuss the production of their drawings, how this has changed, and the use of virtual reality in their teaching studios at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

This interview was recorded in the summer.

Pan Scroll Zoom: Teaching Architecture Under Lockdown: 20 Studios Worldwide That Went Online was published this November. To purchase a copy, click here.

Fabrizio Gallanti: Let’s get started. As, you know, this series is already a year old and has evolved to incorporate issues related to the complexity of architecture and pedagogy, going beyond the initial ambition of reflecting on the roles of drawing in online teaching studios. You have an architectural practice, you do research; you publish, you teach. You explore a multiplicity of ways to engage with architecture, and I have the impression that drawing occupies a central role in each of them, with a quite ample array of techniques and approaches. What adjustments and changes have you noticed in the past year?

Heinrich Wolff: In Ilze’s and my practice there are three distinct modes of drawing production. The first is the kind of collage narrative zines that Ilze makes, which is a very particular way of producing information and telling stories.

The second had its origins during the pandemic. It had to do with the limited tools that I had available to draw with. These drawings are hand-drawn but digital, thinking through architectural issues, from plans to elevations and three-dimensional stuff, to drawings exploring mood and habitation. Some are black and white, like linocuts; others are polychromatic, but they are all digitally generated.

The third mode is also fairly recent and was created in an urban design studio that I taught at the Harvard GSD. It has become somewhat legendary as it is the world’s first collaborative virtual reality design.

The students I teach are all over the world. So, although they were in the same class, they were physically in Los Angeles, Madrid, or Beijing. VR allowed us to interact socially, design collaboratively, and have reviews with all the work next to each other in the same space. In VR we could view the work as plans or 3D models, and teleport into the urban spaces to experience them as a pedestrian.

On one hand, we tried to break new ground with virtual reality, but on the other, here in the office, is an old-fashioned drawing board and next to it a pile of A1 drawings.

FG: These are plotted from a printer, I imagine?

HW: No. These are all drawn by hand. It’s just a black pen. In a year, I could produce 200 of these sheets. There are produced for all projects, from small houses to a very big temple in Kinshasa. We make these huge, spectacular drawings, all drawn by hand. There is a magic to black ink on a white background, which I will never forsake. It is a very fast way of thinking.

FG: And is this something on which your practice is based, and something that you continued throughout the pandemic?

HW: Yes. Because Ilze and I had to suddenly work from home, we carried a drawing board from the studio into the house. So, we draw from here and then photograph the drawings with a cellphone and send pictures out.

Ilze Wolff: The black line drawing is the style that Heinrich and I probably share the most. I mean, he doesn’t make collages and I don’t draw digitally or in virtual reality. But we both draw with a pen.

FG: I think the combination of sudden solitary individual practice with the quick discovery of collaborative modes of production was fascinating. I had no idea about the existence of Zoom until I was forced to use it. Have you reached a common point in your pedagogy, somehow stimulated by this unexpected condition? You teach sometimes together but often separately, am I correct?

HW: Yes, that is something that Ilze and I are quite proud of. As a husband and wife team, we always say that we are not wearing the same tracksuits. We do not slowly become one entity; we are different people with two ways of exploring. So, our work does not necessarily look the same. The way we draw or think or where our minds go are not identical. And that’s what makes this kind of partnership so much fun. We are amazed when other couples can make work that looks the same. They seem to morph into one person, creatively. It’s great that they can achieve this, we just work differently. Yes, we work together and we like each other, we even sit next to each other at work, but it doesn’t mean that our outputs are that of a single author.

FG: Do you think that these modes of operation, where individuality is preserved, are transferred to your teaching? Are you trying to teach the students that you can address the same issues and topics but maintain distinct voices in practice?

And, returning to your virtual reality studio at the Harvard GSD, what was this experience like? Was there a homogeneous final result or was it still possible to feel the imprint and traces of the individuals working on a common project?

HW: It is a very complex question because it refers to the issue of the place of authorship in the production of work. We believe what we do is to graft transformations onto an existing world. Ilze can maybe show you the image of Katriena Majiet on the screen. It’s an image that we’ve used as a mantra for our work. There is a sense that we both design buildings and organise our practice around what already exists.

IW: This idea of the pre-existing reality is crucial to us, as is the idea that the drawings don’t represent something abstract that belongs in the future. We are taught in architecture school that you project with drawings, plans, sections, and then innovation is something that comes in later, after the architecture has been executed.

However, what this image of Katriena Majiet tells us is that architecture can also exist around things that already exist in the space. She constructs architecture around her possessions, and in this case, with somebody already inside it. I think that drawings should better reflect this richness of reality. You’ll notice that in a lot of our plans, we always fill the spaces with stuff, especially if they’re analytical. It’s really similar to what Ralph Erskine or Geoffrey Bawa did. It’s so architecture can really begin to tell a story.

HW: Coming back to the issue of authorship, there’s always a world that precedes the creative act. There are two important issues that emerge from this statement. The first is that we do not want the creative act to be dominated by authorship like in the work of Richard Meier or Zaha Hadid, for instance. I think what makes such work so deeply two-dimensional is that it is dominated by the voice of a singular author. In a country like ours, many narratives have been suppressed, and we really need voices, of various kinds, to be expressed, alongside our own. You still need authorship to be present, but it has to find its rightful place. The second issue is that we live in cities that are produced, overwhelmingly, without architects as the primary authors. As architects, we have to understand how we co-produce the city with the citizens as the primary authors. The fact that Ilze has her own voice with which she’s speaking and that I have my own voice does not mean we are in search of a single, dominant voice. No, it’s just like working with students; our narratives exist in a polycentric world. We don’t want the students to absolutely draw as we draw or to draw like each other.

FG: I notice that layering stories and narratives over material representations of heritage is very important to you. Is drawing a tool to decipher, synthesise and interpret reality? As you said, drawing is generally a projective tool for the future. Do you also believe that as anthropologists or archaeologists, we can mobilise architectural expertise in drawing as a way to make things that are hidden emerge? And, in that way, be the base upon which you can foresee a future?

IW: Yes, I think so. I never thought of it like that, but I do think that we like to evoke the texture of life through drawings. Hence the reason why we like the pen, because you can use it very easily to give that texture that gives a sense of life. With computer drawings or renders, there’s a distance between the emotion and your hand.

I have never thought about this idea of drawing as an archaeological act, which of course it is. It’s common in our practice to first draw the existing building and then draw the different phases of the building, in the past as well as the future.

FG: Heinrich, you mentioned the studio that you ran at Harvard. I assume it required a little bit of technical tuning. When you wanted to create this environment, were you able to develop it yourself, or did you need coders and specialists for the digital infrastructure? How did you end up creating a space that was suited to your needs? Were you all of a sudden in the position of the client asking for a service, or were you sufficiently knowledgeable about the technical possibilities that could direct the creation of that virtual space?

HW: I think I pulled a Steve Jobs on everybody. You know, everybody says that Steve Jobs knew nothing but he built the world’s biggest company by asking the right questions. I worked with a team of people including Jason Stapleton, an expert in virtual reality. He was a sort of four-by-four tech genius. He knew everything about VR worlds, and how to socialise in them. There were also two programmers who had written some interesting software, a virtual reality plugin for SketchUp. When they showed it to me, I said that there were a few things that were essential conditions of us using it for teaching. For example, walking. If we’re representing cities we must reproduce the perspective of the least capable citizen: ‘the pedestrian’. In South Africa, the pedestrians are the people who have the weakest hold on the city, and theirs is a fundamental point of view. VR can reproduce that point of view. An omniscient narrator in literature is like a designer looking down on the master plan. Everything can be seen understood simultaneously, all consequences are known and dealt with. This is a fallacy. First-person narration does not reflect the way cities come about. There’s another kind of narration called a ‘multiple-first-person narrative’. Here’s an example: ‘Heinrich was thinking of going to the office’. Fabrizio said to himself, ‘I’m not going if Heinrich is going’. That is a multiple first-person narration.

We were able to generate a virtual space where multiple people, with their own point of view, can look at the same object and shape the environment.

Harvard got VR headsets and sent one to everybody in the studio. There were some logistical problems in China, so we bought specific headsets and VPNs in China and Korea to make the Chinese networks work around some restrictions there.

FG: When someone modified a fragment of the virtual space was everyone else also exposed to that modification? At the end of the semester was there one collective outcome or multiple and synchronous outcomes corresponding to each of the participants?

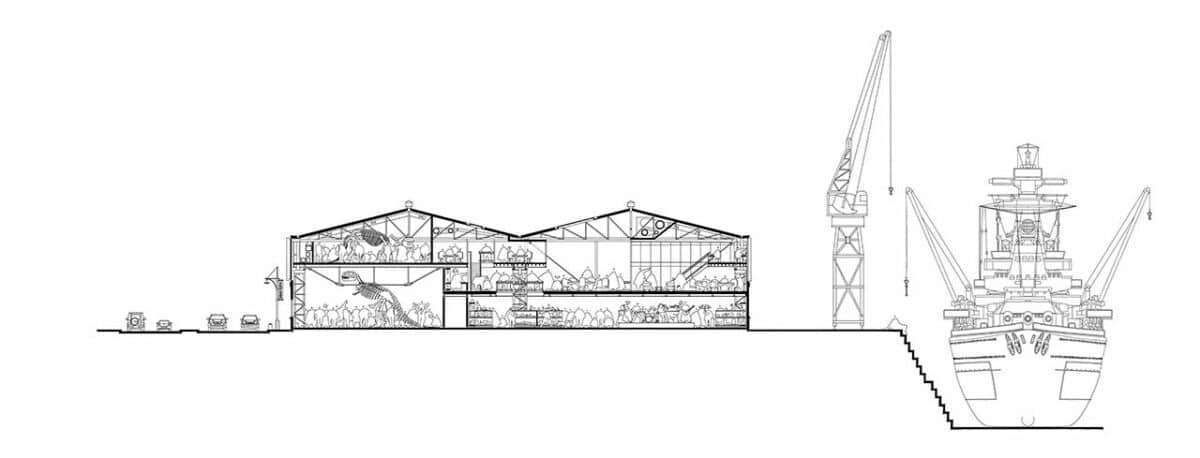

HW: The class was split up into four groups and they each produced their own different project. This is a virtual classroom with people observing a model. You can teleport inside the model and walk around it together.

The lines represent one of us around or inside the models, as avatars. You can either hover in the sky or walk around. I could ask a student, ‘Why did you make this thing here?’, and point to it with a sort of lightsaber. And they would respond by saying, ‘Well, let’s walk down here’. In VR I can have my own experiences. Unlike Zoom, where I’m led by the nose.

There’s also a precise sense of dimension because you can operate at a ‘click-in’ human scale. But then I can pop out of the model and have all sorts of other perspectives. Here, we are all below the digital model.

At this scale, we see the model as an urban structure. This studio was about rapid urbanisation. Notice the highways and contours.

FG: It becomes cinematographic: your eyes act as a camera, and you have movements that we see only in movies. Bridging the analogical with the digital, I have a question for Ilze. In your practice, collage has always been very important. Has the availability of digital tools changed the way you approach it? Architectural representation is always playing with simulacra, and we often use software that imitates manual operations, or vice versa. In the early days of computer-aided design, people were doing things by hand and trying to make them look like if they were plotted by a computer.

IW: A collage is like visual thinking. There’s a thinking process in that moment between cutting and deciding where you are going to stick it on the paper. It’s a form of meditation about what we are seeing. For instance, with one project, the garden was very important. The main material to be used in the collages was about plants. I used pressed flowers. And then all the issues emerging from the representation were about how the plant material could become the visual that was going to frame the plans, frame the text, frame everything in the project.

In another project for the African Mobilities exhibition, we chose three different materials: white paper, brown card and yellow tape. These materials – that made up the models – began to interact in very nice ways. They generated the aesthetic language for the design.

For me, the computer is there just to capture the process, not to nourish it, to scan it in order to hold it digitally. But this is the slowing down of the thinking process. Heinrich scans his hand drawings to make the content available in the digital world rather than producing it digitally.

FG: Heinrich showed me the cell phone he uses to take pictures of your hand-made drawings. We all find ourselves in a time when the almost ideological juxtaposition between the real and the virtual, the digital and the hand-made, seems to be less relevant. And we all operate in this hybrid of both worlds.

Coming back to the virtual reality studio at Harvard, was it also a way to reconstitute the atmosphere of the studio? I got the impression from other interviews that being together in the same space was what was most missed by tutors and students. Some have tried software like Miro or Concept Board to replicate the atmosphere. Is virtual reality a way to recreate a lost community? I wonder how well architectural schools are prepared for what some call ‘phygital’ – a combination of ‘physical’ and ‘digital’.

HW: When I began teaching at Harvard, the first thing I asked was, ‘Aren’t you tired of Zoom? Why don’t we move this thing forward?’ and everybody was saying, ‘How?’ Nobody knew, and the fundamental proposal was not about virtual reality. The conversation was about socialisation and collaboration. I am convinced that learning from your colleagues is the most fundamental learning that occurs at the university, richer than what you learn from instructors. There are two kinds of learning. One is instructive learning, where a professor is standing on the podium, giving a lecture – quite old school. And then there is constructive learning, which has to do with more situated, engaged learning.

The socialisation that occurred during the studio was quite significant and was analysed by the Harvard Innovation Task Force. They canvassed students’ comments; and one student said, ‘I’ve been sitting for 18 months in an apartment, by myself, hardly seeing other people. Now, suddenly, I’m around a table with people that I’m producing work with. I’m back in a studio as if I were in Gund Hall.’ When I gave the students the option to work in groups or individually, nobody opted to work by themselves, citing, ‘We’ve been working individually for too long.’

There are a plethora of programmes and you just move between them. I have a cell phone, a digital drawing pen, a drawing board, a sketchbook, there are some VR headsets. It is a little bit messy but to have a certain fluidity with that fragmentary landscape is important. I think that’s why Ilze and I are happy to see these practices within our own office, it’s how people co-exist.

FG: It is a refreshing feeling compared to the moment when computers first appeared in architecture schools, inducing a very naive collective love – especially from professors or early high-tech adopters – for all the potential that new software was going to bring to architecture. Now there’s slightly more scepticism about the potential of software and 3D printing and all these tools that, in the end, have not produced as much as they have promised.

IW: I have a similar opinion around these various technologies: they should just be techniques for producing ideas. What I want to hold onto is the technology of storytelling. I think there are some really nice technologies that are coming back into the world, for instance, radio, through podcasts. And I think that drawing has the potential of coming back as a simple and very efficient way of communicating a story.

FG: Do you think the strength of these tools, such as scissors and glue, depends on the fact that they’re a lot faster than the digital version? Frank Gehry used to say that he never wanted to learn to use computers because whenever he sat by one of his collaborators he would get frustrated by how slow things were on the screen. ‘When I have an idea, I just sketch it and in seconds I have it, then I give it to someone else who will spend seven hours putting it into a computer.’

HW: The statement about a pen being faster than a computer is true; we’ve been saying it for years as well. Ilze can testify that if we are under pressure we sit and draw a project from initial design concepts right through to the technical details in one night – by hand. It’s like one mad flurry. The whole drawing is being conceived and issued in a day; we bypass the computer because that process would take too long.

IW: If you want to tell a story in a quick way, do a pencil sketch and if you think that’s adequate, don’t replicate it in another medium.

FG: Do you think what you did at Havard is scalable or usable in other pedagogical contexts that do not have the same resources? Shipping VR headsets to the four corners of the planet is something that not many other schools could afford. Do you think that other lessons in that exercise can be adapted to low-tech environments?

HW: Sometimes people assume that you can only advance something like VR in environments like the ETH or Harvard and then the methodologies are applied in the third world. This assumption can’t be further from the truth, because we come from the third world. We developed things here that we teach people within Switzerland or the United States.

To visualise the processes of rapid urbanisation in Goa, India, we did a chalk animation on the wall. I asked the university there what infrastructure they had and their answer was, ‘nothing.’ I said to them, ‘Do you have a wall?’ And they thought I was being facetious. And I said, ‘Really, do you have a wall, and can you paint it black by the time I arrive there?’ They said, ‘yes’, and I said, ‘I’ll bring chalk.’ We used my camera and took photographs, put the images together in simple software and made a stop motion animation. Later we repeated that technique at Washington University in St. Louis with an equal focus on rapid urbanisation. So this can be done in Kabul, in Kinshasa, in China or South Africa, anywhere. By the time I was invited to teach at Harvard, we had adapted a system that comes from the Third World to the First World. The idea that people who don’t work in wealthy places are always on the back foot and have secondary knowledge is just a false assumption.

At Harvard, I asked: ‘Can you please buy a headset for everybody.’ And they said, ‘All right.’ And they did it. But it is born out of third-world methodologies, not Harvard.

Somehow, the pandemic has reversed many conventions. At Harvard, I was appointed to teach in what they call an option studio. The option studios take students to places like Kabul or Nairobi. They want to learn from somewhere else. If they had everything that they need to know back in Cambridge, they would just stay there. As it was impossible to travel, we basically brought the world to the students instead. The difference between Cambridge and elsewhere is probably infrastructure, like Wi-Fi speed or storage capacity. We knew that we might encounter some technical challenges with connections and file sizes, so we made some limitations. We restricted the maximum file size of the students to 500,000 PLG. We were developing a massive metropolitan urban design, so if you look at the trees, for instance, they look rudimentary. The resulting images were quite crude because we limited the poly-count of the total model. This was also so the students with the slowest Wi-Fi could participate equally. It comes out of an equitable attitude towards all the students. We scaled the whole process down to the capability of the weakest system.

FG: What do you think, in general, about the experience of this past year and a half? Has it already had an impact on the way you think and produce architecture?

IW: I can’t get away from the fact that it was and still is frustrating. There were certain things that I enjoyed about being still. It was really a gift, an opportunity, to be in one place – either the house or the studio. And there were these odd moments when you go through a virtual portal and enter another space to connect with students in other parts of the world. That was the silver lining of Zoom. But as soon as you leave the meeting, you are back into your own corner of the physical world again. Before the pandemic, we used to have lots of public discussions or exhibitions in our office because we think architectural thinking is a space for learning that goes beyond the training offered to people already interested in architecture as a discipline. In addition to my architectural degree, I have one in public culture. How do you develop a public culture around architecture? Pedagogy is one possibility, and exhibitions or public events are other ways, but this all came to a screeching halt.

FG: Will it continue to be a hub for these public activities?

IW: Prior to the pandemic, it was a hive. Every month we had something happening, organised either by us or other people in the office. I’m sad that it stopped and that we can’t gather in the ways that we’ve been able. There is something about physical presence and about taking the time to make that happen that is missing.

HW: They say absence makes the heart grow fonder. It’s terrible not to work with your colleagues. We don’t have an enormous office where we don’t know who works there. We know each other, and Ilze and I can appoint people we feel we are going to get along with. And we do. It’s difficult to be separated from people you like working with. There’s also something focused about working at the office, different from working at home. It’s a place of common purpose. And then there’s the public dimension Ilze mentioned that’s also very important. It’s a way we put ourselves out into the world. We share our ideas there, we hear what people are saying, we even meet clients. You set an agenda through the public culture that you advance.

During the pandemic, the survivors were those who could think on their feet and adapt. The people who couldn’t adapt are now completely broke. It is a brutal time that requires imagination to survive.