Dugourc’s Playing Cards

After the journée of 10 August, Jean Démosthène Dugourc sought to distance himself from Etienne Anisson-Dupéron. He turned his attention from wallpaper to playing cards, leasing a space with his Jacobin business partner Urbaine Jaume in the former warehouse of the Académie royale de musique, down the street from the hôtel de Longueville. [1] Officially patented on 17 February 1793, a little less than a month after the king’s execution, the thirty-two cards were printed in woodcut and hand-colored on a single sheet, after which some were cut into official decks. Perhaps in anticipation of the popularity of the cards, Dugourc and Jaume requested permission from the Minister of the Interior to expand the premises of their factory. The petition is dated to 22 February 1793, just six days after the cards were officially patented, and includes a plan of the manufactory located on the third floor of the building. The partners hoped to expand the space to include lower floors and secure street access on the rez-de-chaussée. [2] Seeking to distinguish his new enterprise from his previous activities, Dugourc issued an advertisement that informed ‘our fellow citizens that no wallpaper is produced or sold at all in our manufactory of new Republican playing cards, rue Saint-Nicaise’. [3]

Prior to the Revolution, cards had served as a stock subject matter for artists, from the vanitas paintings of seventeenth-century artists such as the Le Nain brothers to the meditative work of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, such as Boy Building a House of Cards (1735). Besides vanitas, cards were typically understood in the eighteenth century to stand for the hierarchy of the social orders, with the whole deck invoking the totality of feudal society. [4] Such a social understanding was clearly what the government had in mind when it decreed that cards had to be entirely reformulated in order to reflect the new principles of equality after the downfall of the monarchy. As a class of print, the playing cards reached a far wider audience than the Arabesques, evidenced by the numerous copies made of them. Moreover, their currency as print was emphasised by the fact that playing cards were used as substitute forms of local money and billets de confiance (notes of trust) in colonial France, where both metallic money and paper were scarce (below).

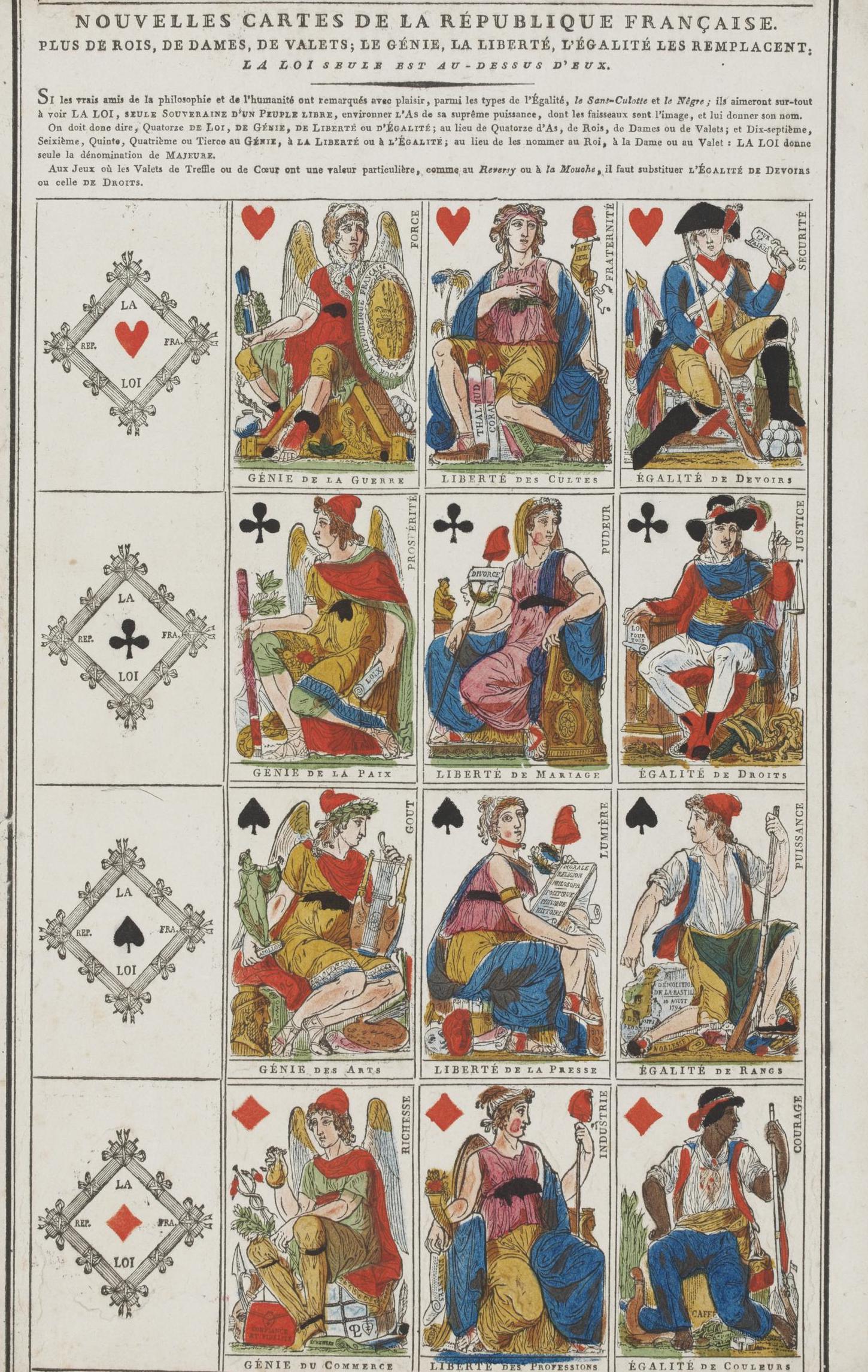

Even as Jaume and Dugourc insisted that their aim was simply to replace royal figures with the embodiments of revolutionary ideals, the playing cards had complex systems of meaning that once again recalled arabesques. Designed as a piquet deck, Dugourc and Jaume’s set includes thirty-two cards instead of the typical fifty-two cards found in a poker deck. There are slight variations among the rare surviving sets. For example, each of the face cards from the earliest version of the deck, dating to year II, bears an inscription at the bottom that states ‘Dugourc, inv. l’an II de la République, par Brevet d’Invention’. By contrast, the face cards in a hand-colored set at the British Museum lack his name as the inventor and are accompanied instead by a copy of a proposal for the constitution of year III. As Thierry Depaulis notes, Dugourc and Jaume’s pack was the first deck of cards to have been officially patented, transforming what had been a somewhat generic signifier of social order into a specific form of intellectual property over which Dugourc and his partner sought authorial control. The new laws on patenting inventions in 1791 replaced the previous system of privileges and titles that had been granted by the royal administration. The variations in sets signaled the ways in which the cards could have multiple functions, serving on the one hand as public advertisements of Dugourc and Jaume’s claims over the rights to the design or forms of revolutionary propaganda when accompanied by the constitution. On the other hand, the ghost of Dugourc’s father looms in the background of this endeavor. For the patent indicates an attempt to seize authorial control in order to ensure that the legal battles over the rights to invention that had once brought his father down would not do the same to him.

Refiguring the family romance of the French Revolution, the cards replaced the paternal kings, maternal queens, and filial jacks of the traditional deck with personifications of Genius, Liberty, and Equality. On the reverse side of the republican cards stood the abstract diamond shape of the law formed from four joined fasces, which also replaced the aces in the deck. The woodcut designs are intentionally coarse, a stylistic regression from the fine etched lines of Dugourc’s earlier, more accomplished engravings. The harsh bludgeon-like work of cutting across the grain of wood to produce figures is found not only in his playing cards but also in the woodcut letterhead designs of this period. All the same, there is a refinement in the masterful arrangement of figures, text, and ornaments found on each of the face cards, and the creation of a new cast of characters, who, in their doubled figurations, evoke the compositional strategies found in the Arabesques. Deciphering each figure requires relying on the prospectus. The ‘geniuses’ of the deck resemble classical gods, such as the winged ‘Genius of Spades, or of the Arts’, who holds a lyre and a miniature Apollo Belvedere. The ‘Genius of Diamonds, or Commerce’ resembles Mercury and holds a caduceus in one hand and a bag of money in the other. While his pensive figure indicates his ‘profound specula- tions’, the portfolio, papers, and book at his feet demonstrate ‘that confidence and fidelity are the primary foundations of commerce, just as exchange is the means, and order creates security’. [5] Alongside the ‘Liberty of the Press’ and the ‘Liberty of Religion’, the appearance of the ‘Liberty of Clubs, or Marriage’ is surprising, since she is shown wielding divorce papers in her hands. The device is intended, the authors assure their fellow citizens, as an apotropaic ‘amulet, that must ceaselessly remind spouses that their fidelity must be mutual in order to be enduring’. [6] The figures of Equality bear a remarkable specificity, corresponding to new patriotic types that had emerged out of the Revolution. Though there are no tricoteuses, the ‘Equality of Hearts, or Duties’ represents a member of the National Guard, while the ‘Equality of Clubs, or Rights’ is a judge who wears a costume similar to the designs that David had invented for members of the government.

By far the two most radical figures are the ‘Equality of Diamonds, or Colors’ and the ‘Equality of Spades, or Rank’, represented, respectively, by a liberated Black man and a sansculotte. The Equality of Diamonds goes one step further than any abolitionist image of the period in figuring freedom, not as a freewheeling entanglement of arabesque motifs but as an armed black man (above). Calling to mind the Black Spartacus envisioned by the Abbé Raynal in Histoire des deux Indes, this avenger of the New World is shown unchained from the fetters of slavery and enjoys ‘the new Pleasure of being free and armed: on one side one sees a camp, and the other sugar cane, and the word Courage finally avenges the Man of Color from the scornful injustice of his oppressors’. [7] As a parallel allegory, the armed sansculotte grips the muzzle of his musket with one sinewy hand, while he points down at the crumbled remains of the ‘demolition of the Bastille’, chiseled with the date 10 August 1792. The date of the fall of the Bastille on 14 July has been collapsed with 10 August, a maneuver that is not entirely explained in the prospectus.

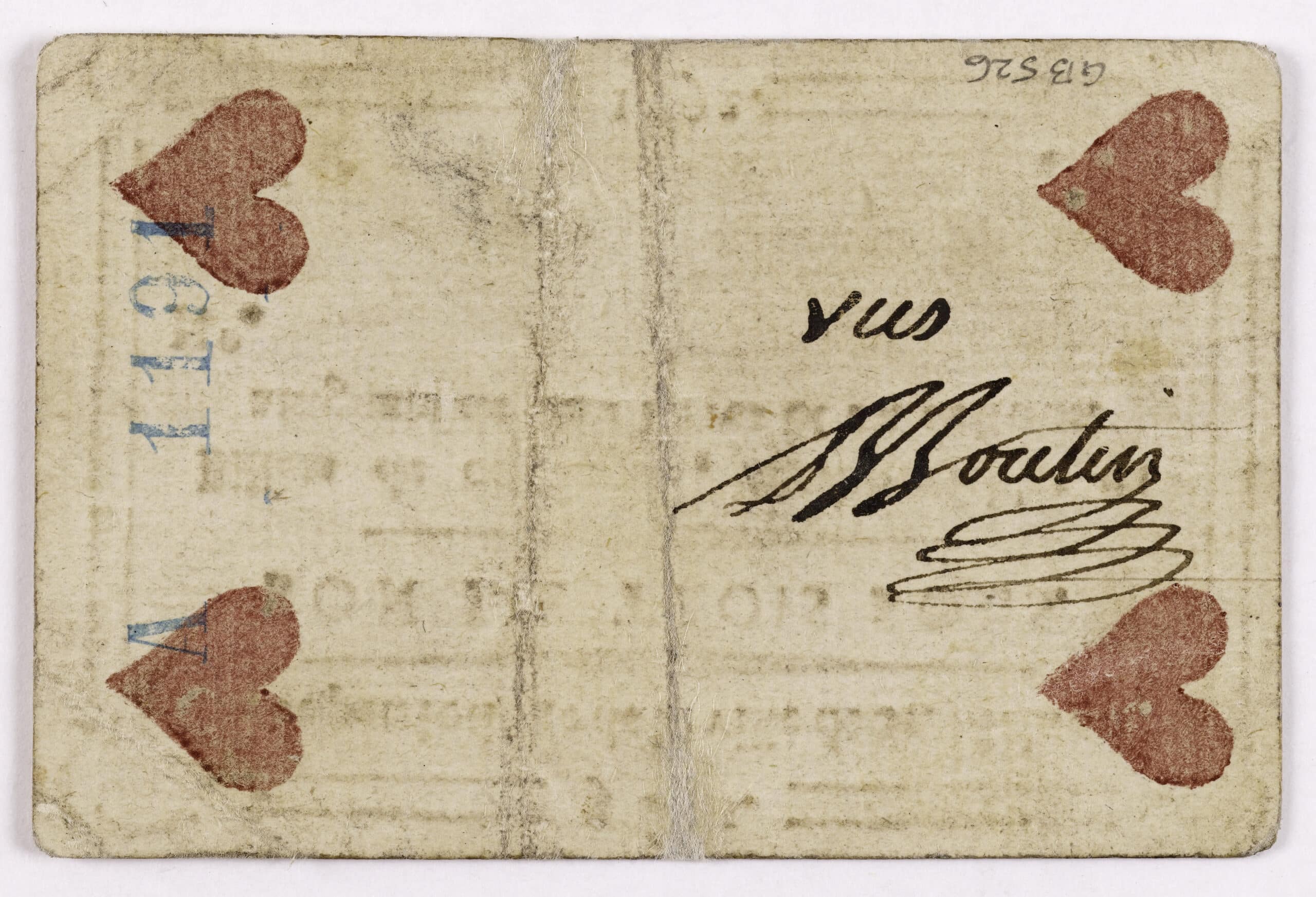

While the society augured by the republican playing cards overturned the hierarchical order of the royal deck, the cards relied on the compositions of the past for their symbolic effect, much like the propaganda prints of the period. Hence the adoption of seated figures recalls the former royalty found on playing cards, in order to evoke ‘a mass equal to the Magots from the age of Charles VI, and one took care to preserve the same colours, in order to offer the same effects’. [8] A number of the decks had, in fact, been printed upon old card stock embossed with a fleur-de-lis pattern left over from the ancien régime. Though royalists used hidden rebuses and repurposed prints to serve as secret counterrevolutionary calling cards, the fleur-de-lis watermarks represent the last ghostly traces of the ancien régime’s tax system.

The monarchy had regulated gambling instruments and, since 1751, had required card makers to use a particular type of card stock with the fleur-de-lis, which served as a tax stamp allowing authorities to distinguish between duty-paid cards and illegal examples. When tax regulations were lifted, remaining stocks of perfectly watermarked paper continued to be used until 1800. Thus, one found ‘perfectly republican playing cards, made during year II, on this paper watermarked with the fleur de lys’. [9]

The more one looks at this pack of playing cards, the more the revolutionary manual of the future comes undone by the plenitude of attributes that surround each figure, and the didactic messages become so many slogans layered one upon another in a semiotic mesh of words that never quite mean what they say. [10] The same is true of the letterhead designs created by Dugourc and his collaborator Jean Louis Duplat, which have a crowded quality, as if the ancillary decorative elements are fighting their way to occupy center stage and replace the primary emblems, in a redeployment of arabesque squiggles meant to undo the purposiveness of revolutionary iconography. Functioning as dialectical objects rather than foolproof pieces of propaganda, Dugourc and Jaume’s cards embody the ways in which the visual culture of the ancien régime – full of pleasure, play, frivolity, and risk – persisted, the material traces of the past serving as the physical support for the serious work of the present.

Extracted, with permission, from Luxury After the Terror by Iris Moon, published by Penn State University Press, available here. An exploration of Dugourc’s time in Spain after the Revolution, also extracted from Luxury After the Terror, will be published later this week.

Notes

- Baulez notes that the lease for the space at the hôtel de Longueville was dated January 26, 1792, while Anisson-Dupéron signed a private agreement for the partnership with Dugourc and frère Gouron on January 31, 1793. However, Depaulis indicates that the wallpaper business ended in March 1793. This means that there was an overlap between Dugourc’s participation in the wallpaper enterprise and his playing card partnership with Jaume. See Baulez, ‘Imaginations de Dugourc’, 43n80.

- I am grateful to Paul Harper for his help in researching Dugourc’s card business.

- Depaulis, Cartes de la Révolution, p.20.

- Scott, ‘Chardin and the Art of Building Castles’, p.41.

- Dugourc and Jaume, Nouvelles cartes à jouer, p.2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p.3.

- Ibid., p.4.

- Author correspondence with Thierry Depaulis, 4 May, 2016.

- On the importance of language and linguistic signs in revolutionary politics, see Sophia A. Rosenfeld, Revolution in Language.