Retreat and Commemoration: Heath’s Court, 1878–82 – Part 2

This post continues with the second part of Nicholas Olsberg’s text on William Butterfield’s Heath’s Court project, included in his new book The Master Builder: William Butterfield and his Times to be published by Lund Humphries in October 2024.

‘Cycles of the human tale’: the library

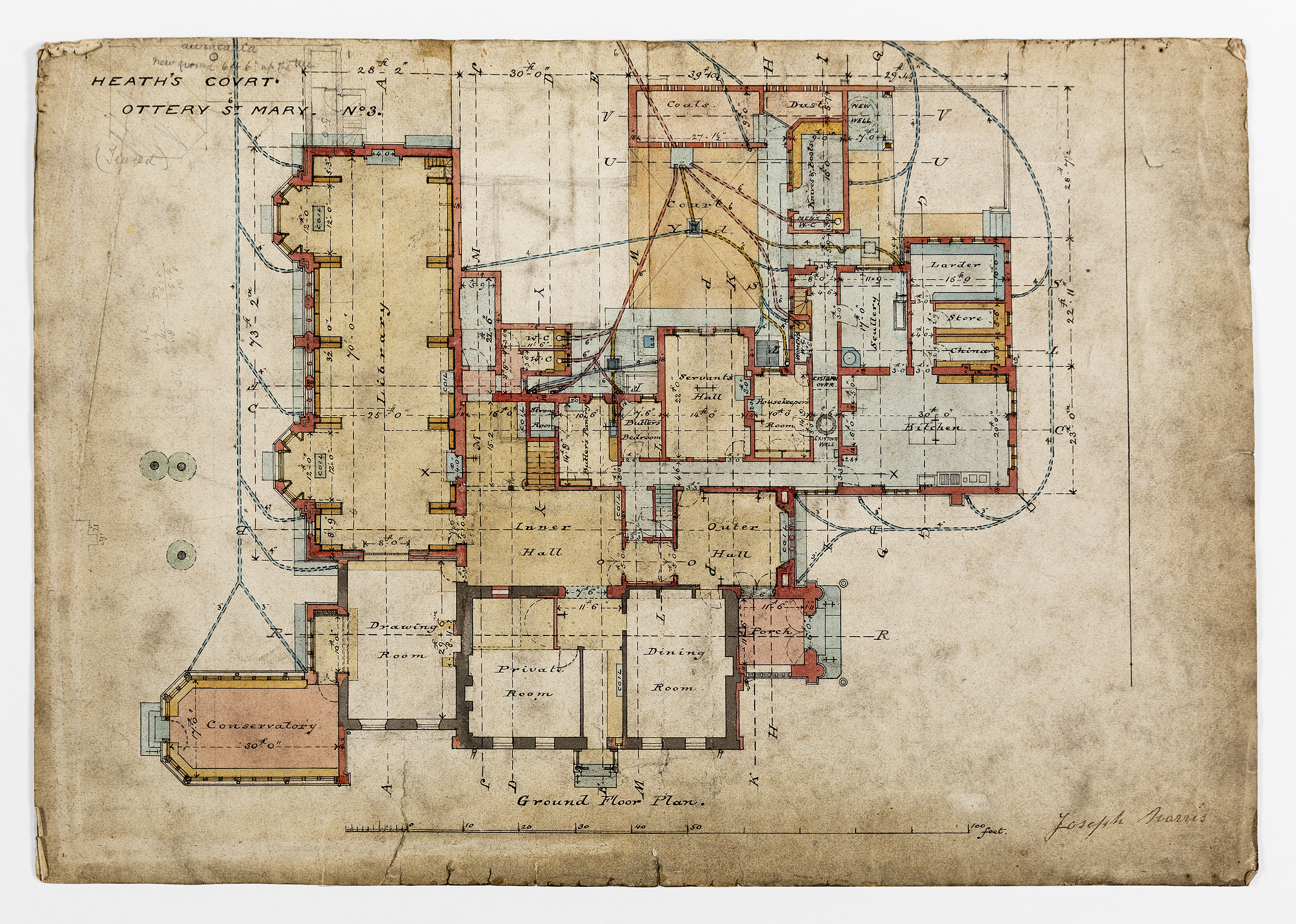

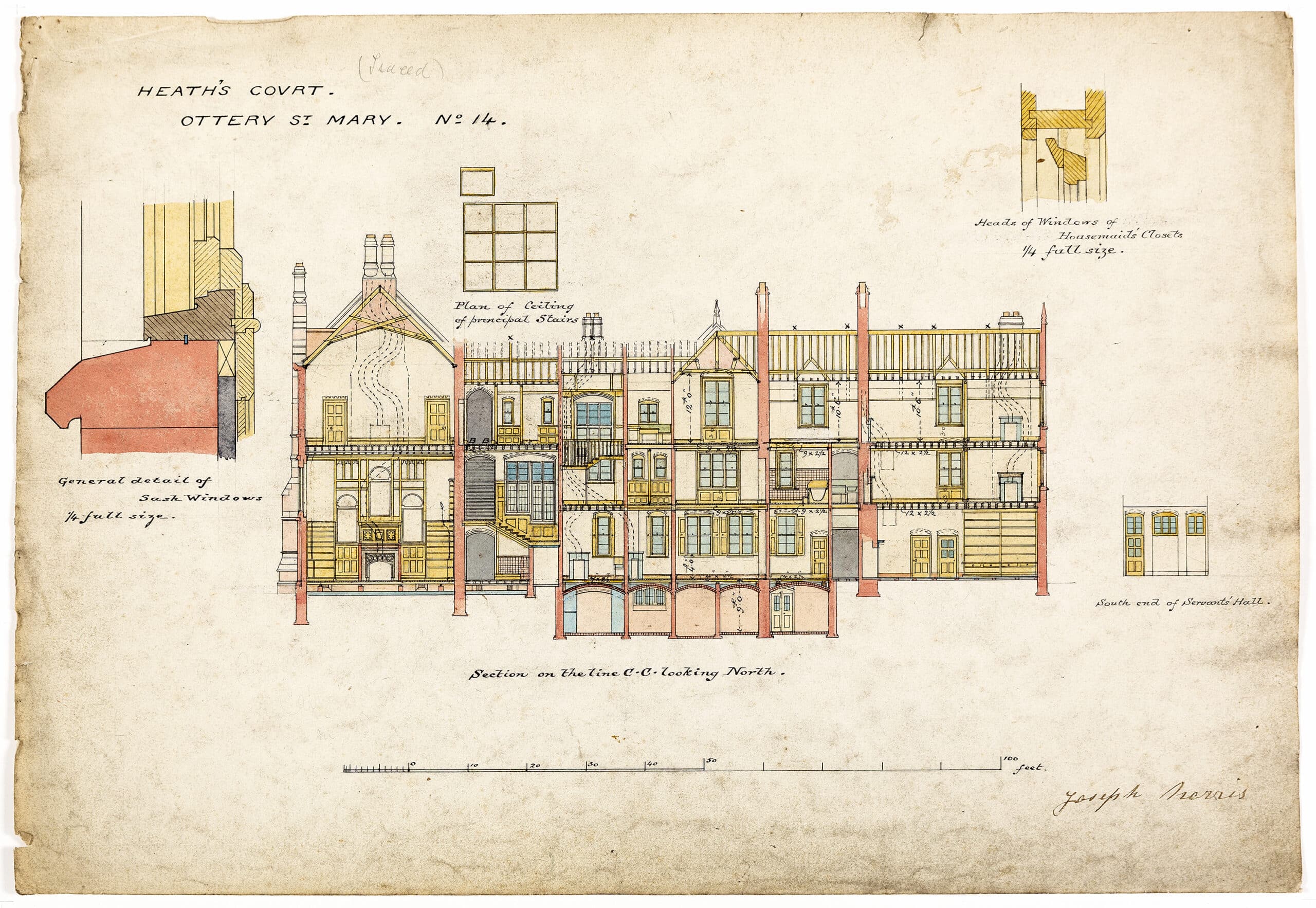

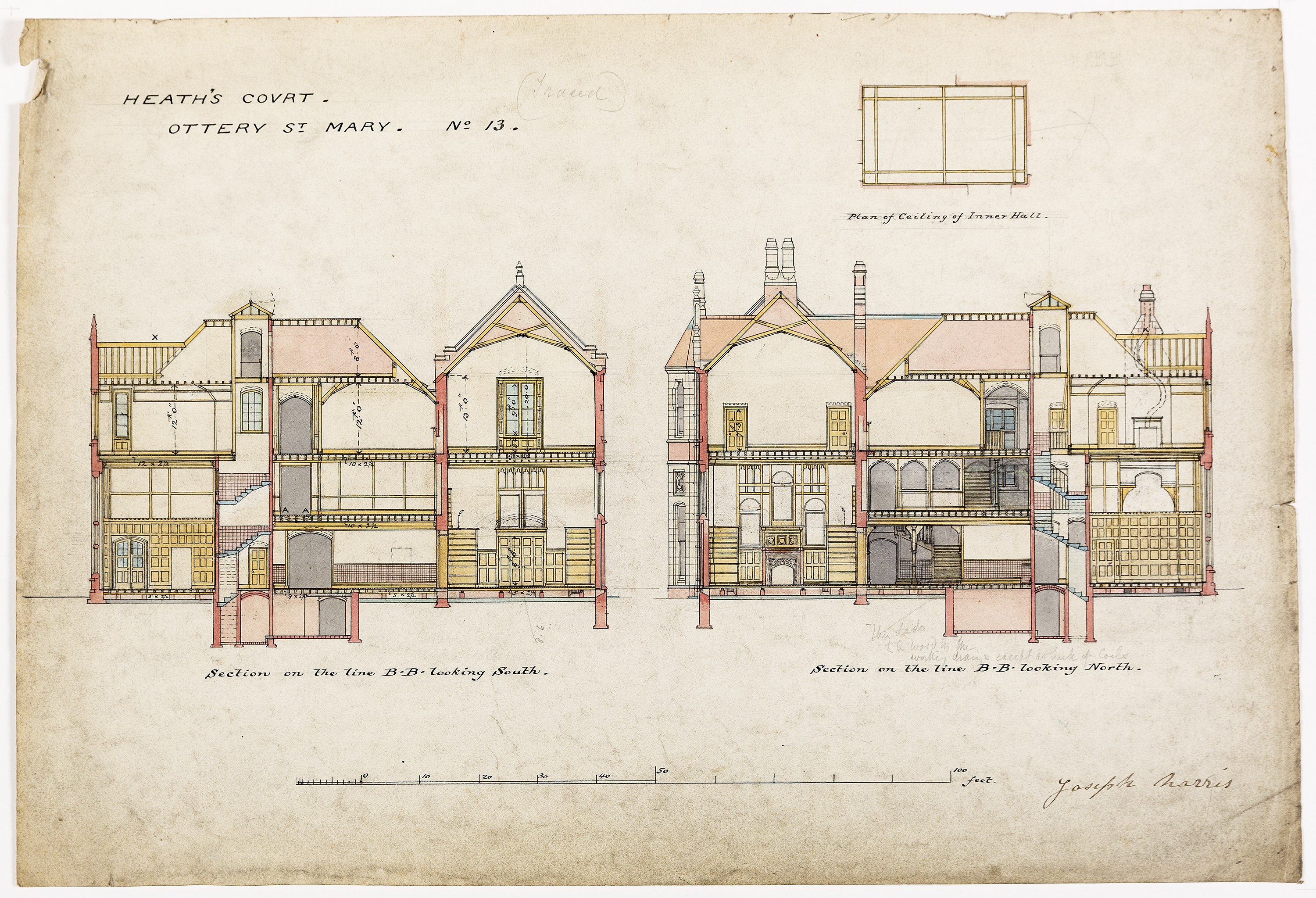

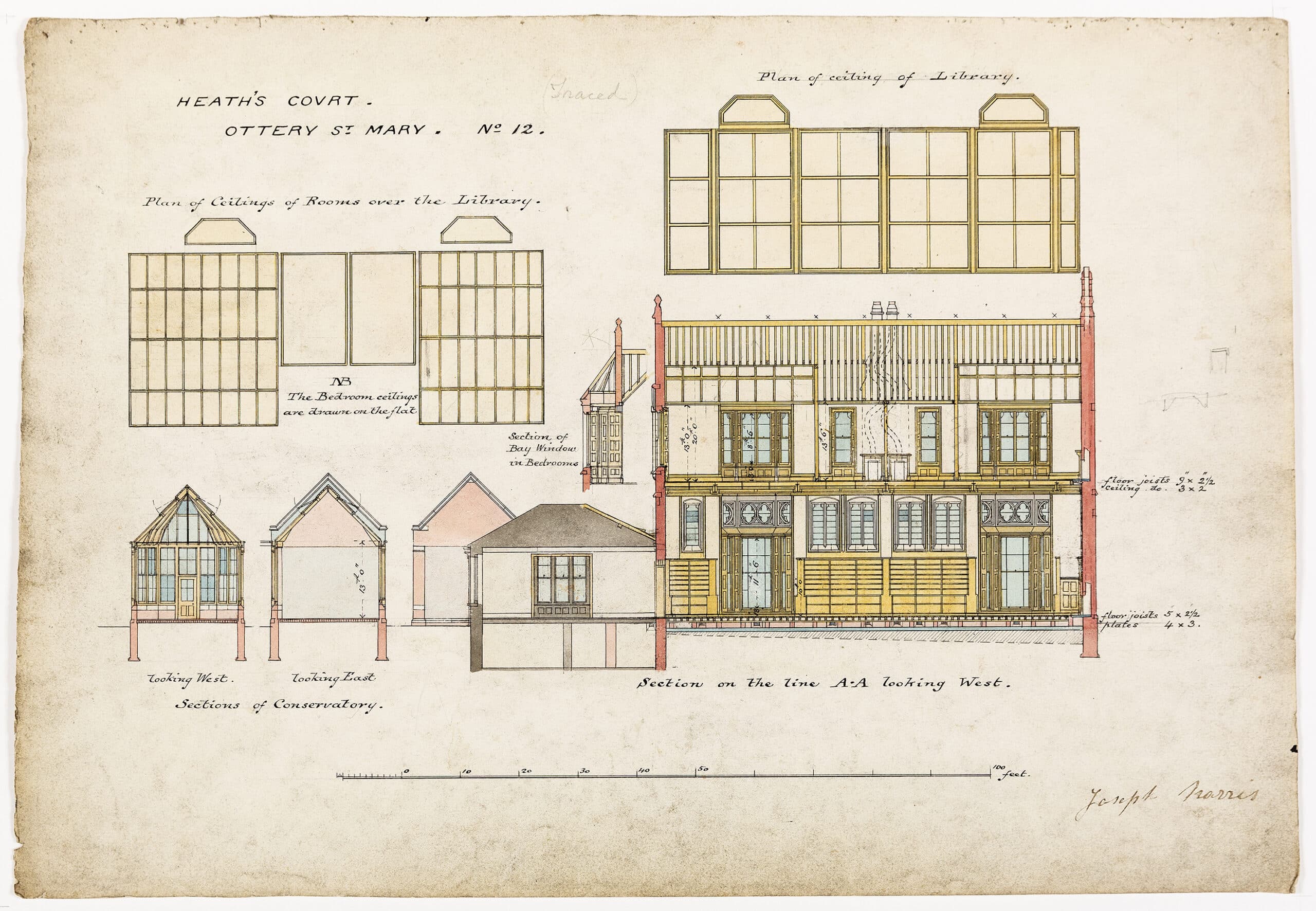

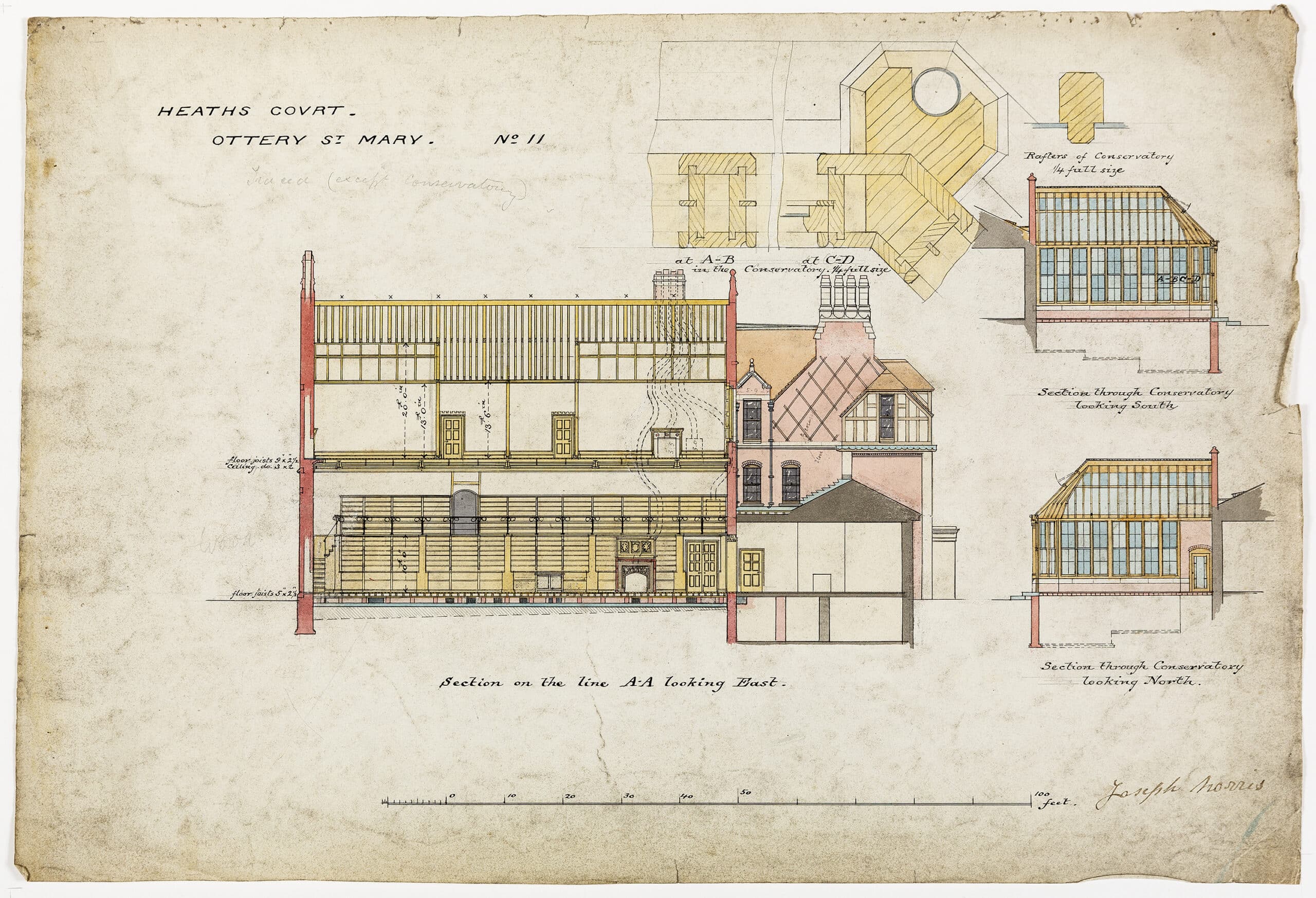

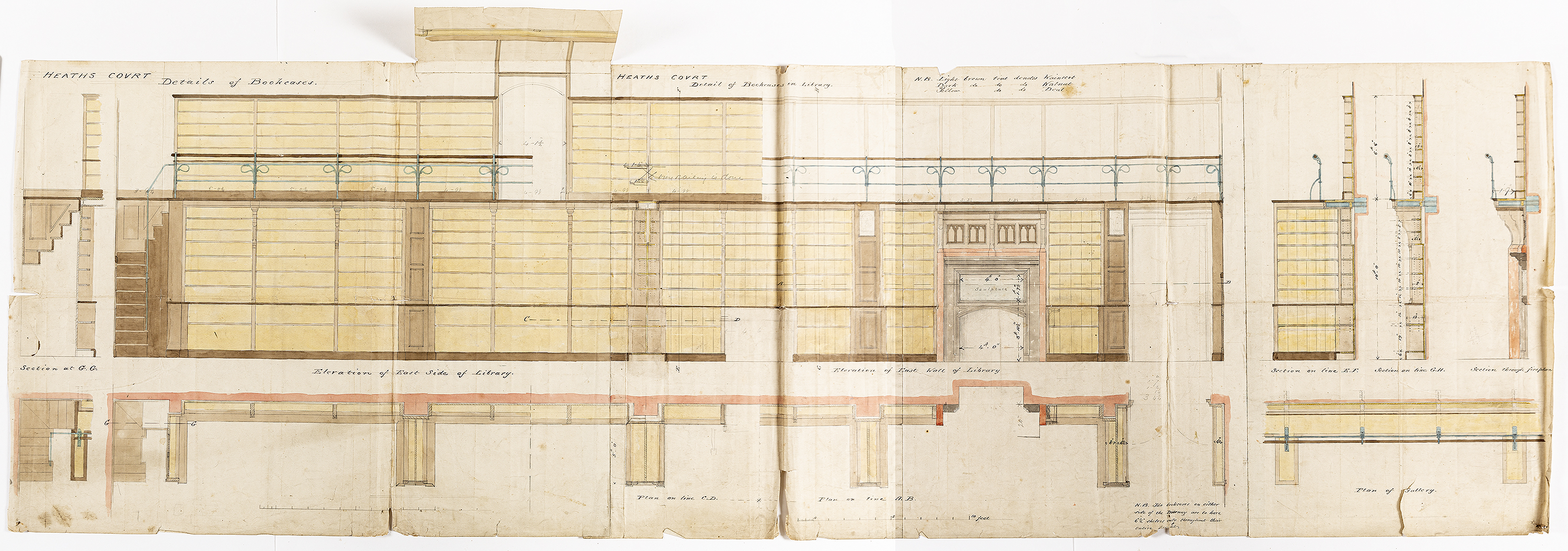

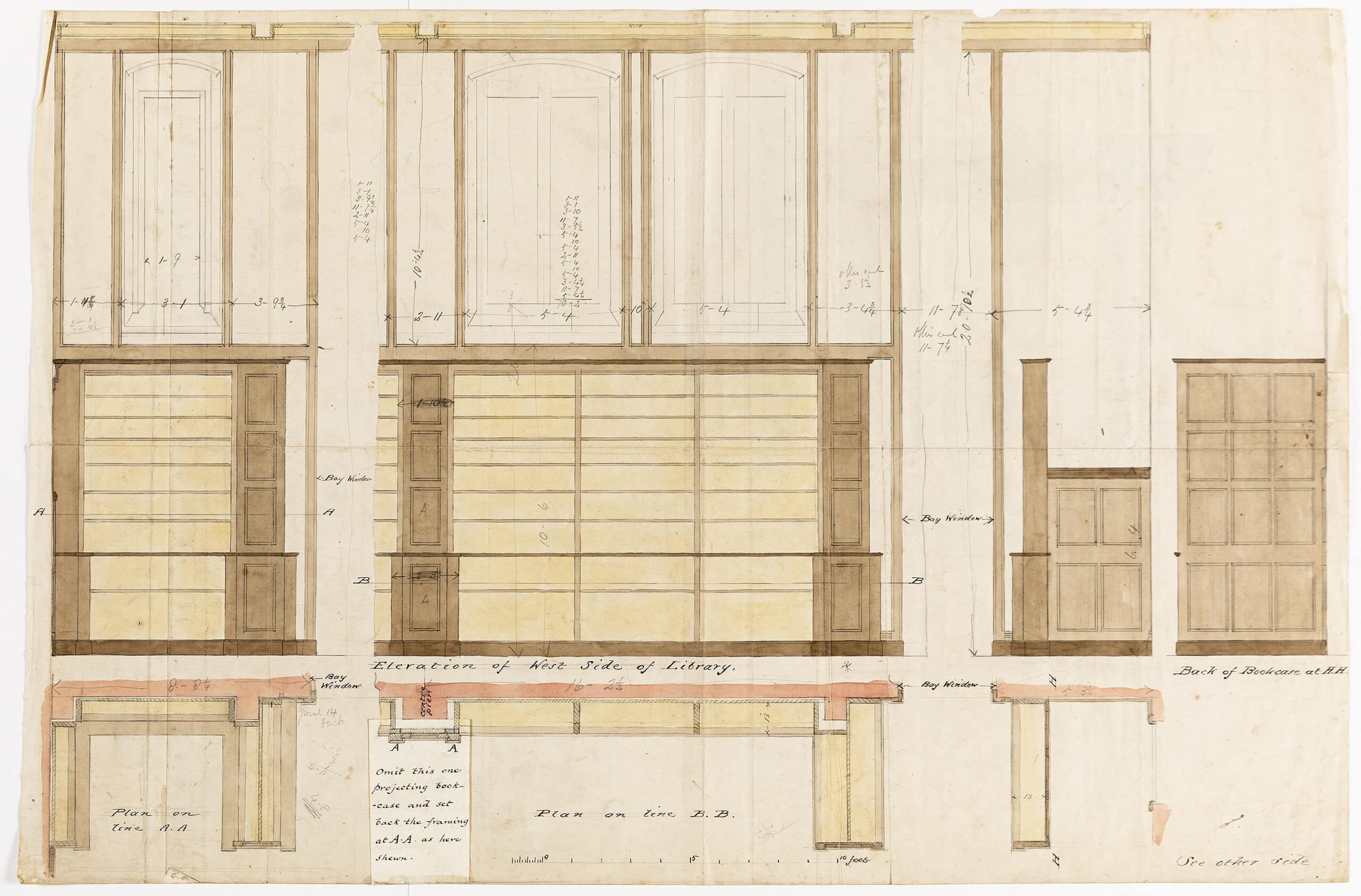

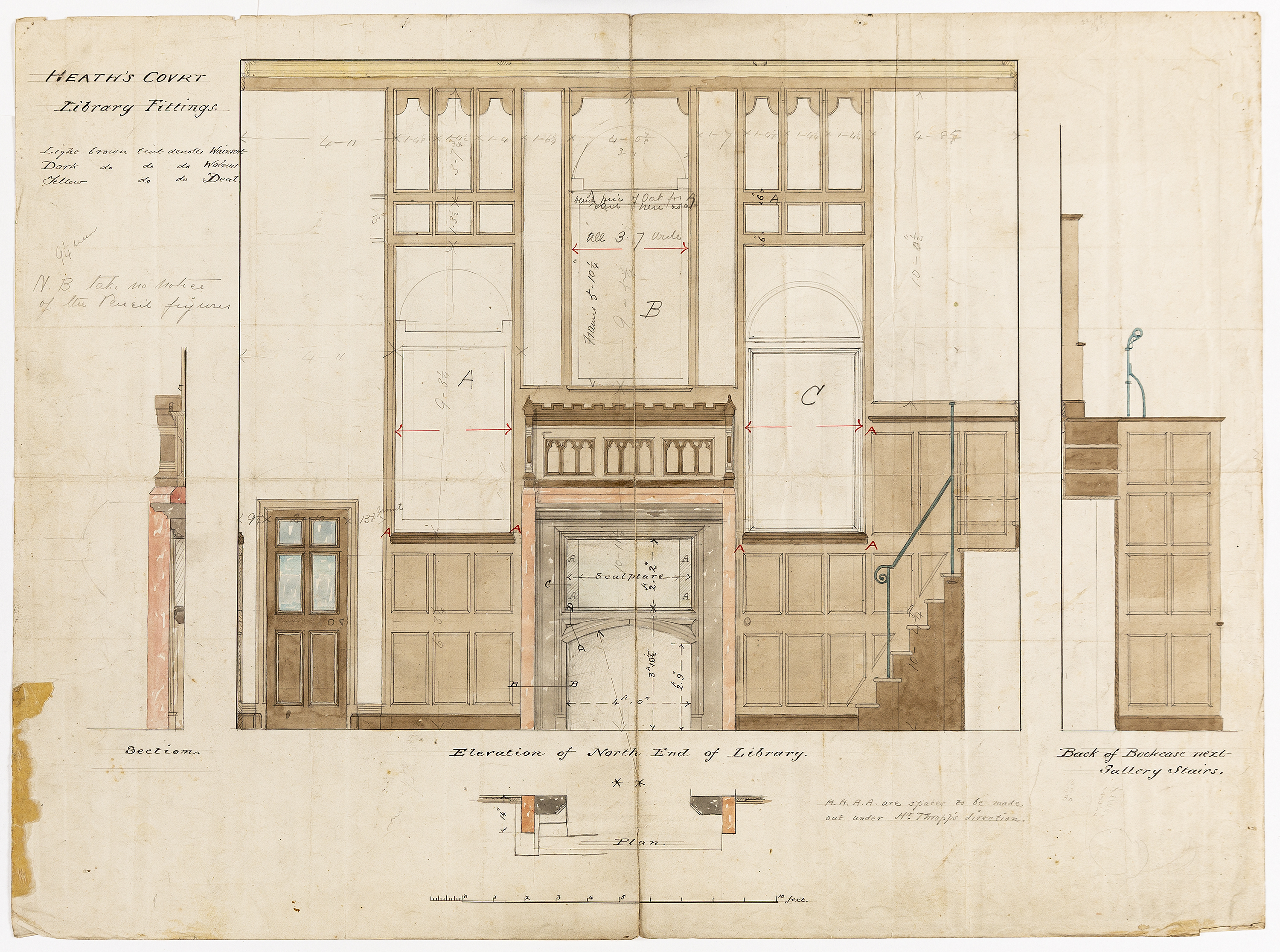

The elevation of the library’s north wall, as we see it in the general sections, would be modified in details to admit a door on the north-west corner leading to the new conservatory. At that point the carved overmantel would be replaced by a Thrupp frieze after Flaxman showing Athena’s dismissal of the Furies, from Aeschylus’s Eumenides, with an inscription—‘They say that Justice is the child of God and that she dwells hard by the sin of man’, and the word ‘Andromeda’ placed above it—all reflections on crime, punishment, sacrifice and the foundation of civil society. Above are frames for three of Jane Coleridge’s full-scale drawings after two Sistine Chapel sibyls and the prophet Jeremiah, brought from Sussex Place.

Two frames at the south end carry more Michelangelo studies by Jane, one after the Bruges Madonna and the other from the sketch published in William Young Ottley’s The Italian School of Design of 1823 as a study for his Sistine Isaiah. To the left and right the panelling would soon after be modified to hang two enormous cartoons, rejected long ago for Old Testament frescoes at Wyatt & Brandon’s Italianate church in Wilton, near Salisbury, by Sir William Boxall, Butterfield’s friend and travelling companion and Jane Coleridge’s teacher: these recount the expulsion of Ishmael and Hagar and the Prodigal Son.

A second Thrupp bas-relief above the fireplace in the east wall is taken from William Blake’s 1817 vision of Hesiod’s ‘golden age’, in which mankind was imagined dwelling under the shelter of a first perfect rule of law. [1] This whole elaborate iconographic scheme contemplates the prevision of civil and divine justice, the founding of nations and the construction of a peaceable society. Busts of John Milton and other writers stood on the library bookshelves. Carved wood fragments salvaged from the Ottery church during the 1849 restoration appear as end panels in the shelving.

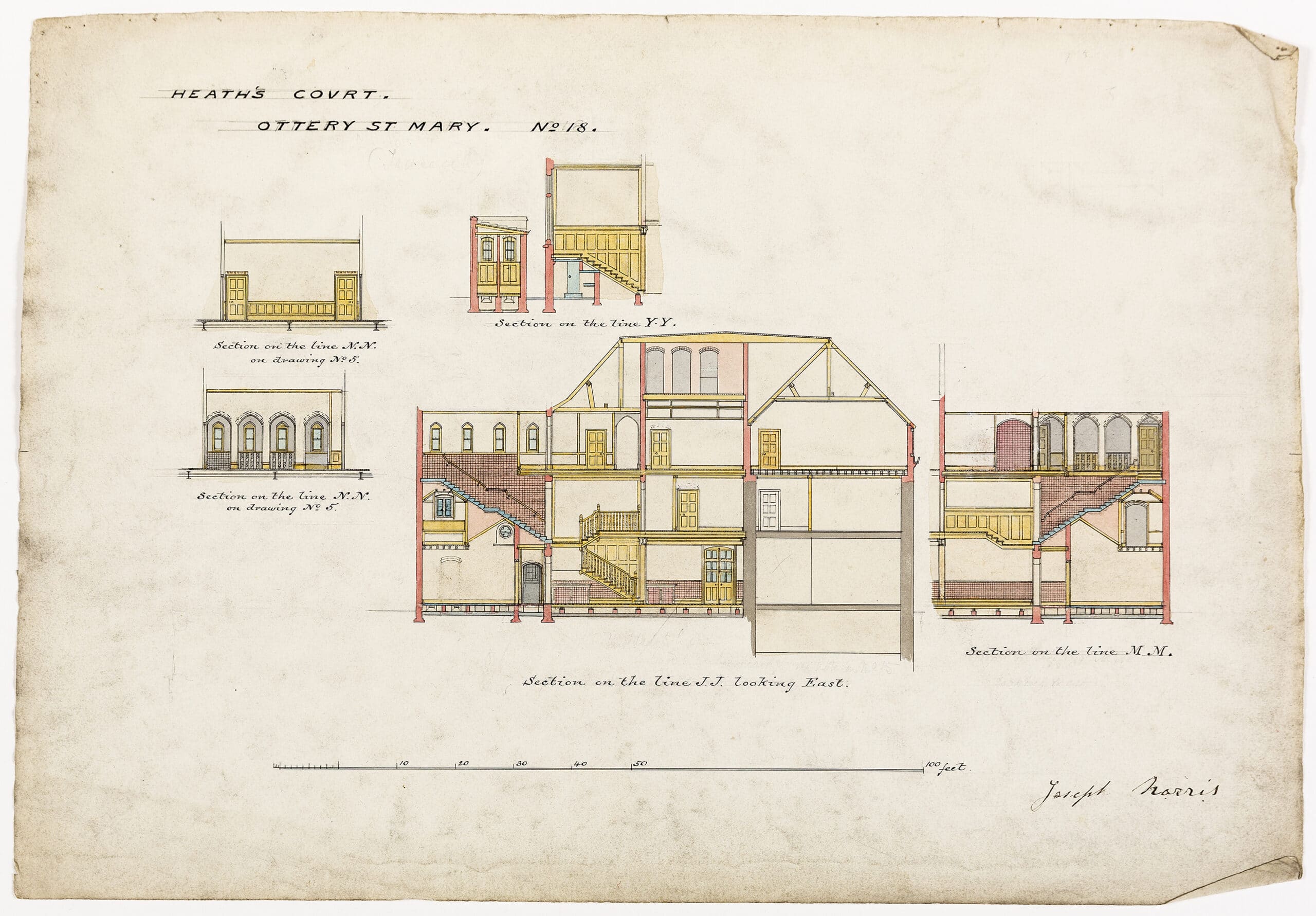

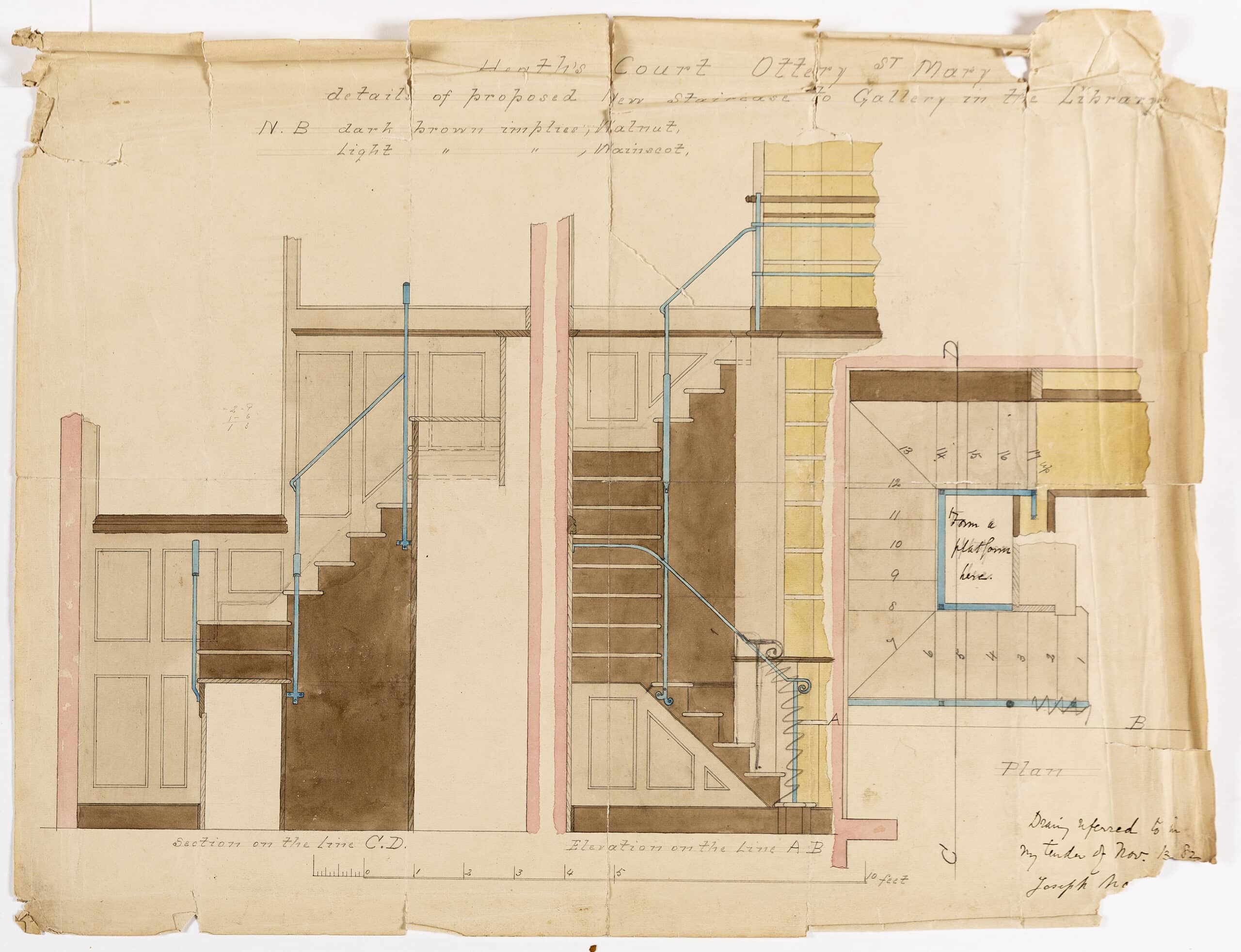

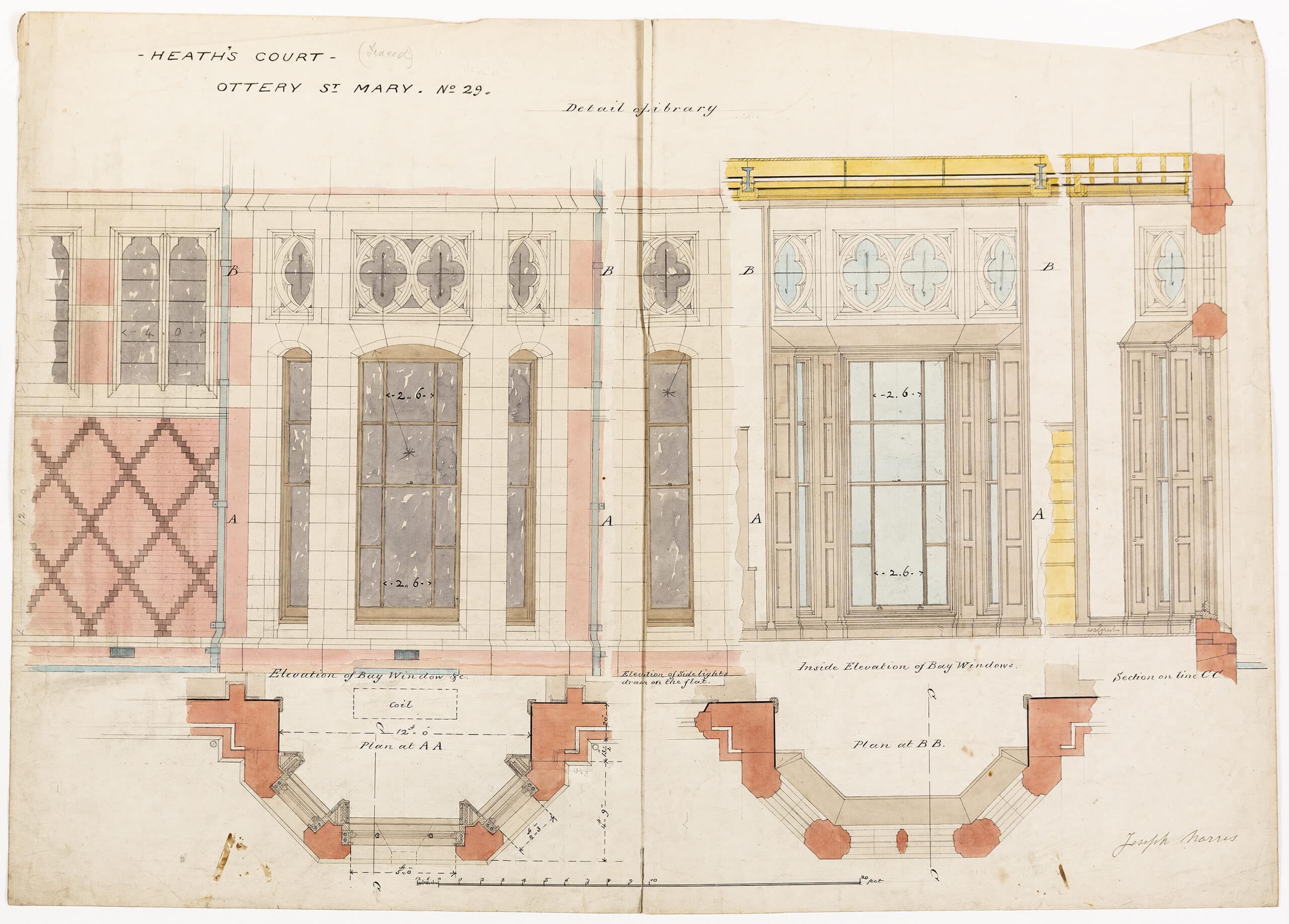

Coleridge’s private collection of books was one of the largest in the land, rich in print folios and illustrated books, from the late fifteenth-century Nuremberg Chronicle onwards, which only a setting at the scale and openness of the Heath’s Court library could make comfortably accessible. A sequence of 12-foot bays allowed discrete study alcoves, with moving steps, stairs and tables making the maximum use of available space, and a full-length gallery of shelves along the east wall. A small door off the gallery leads to what was at first intended as a studiolo but then redesigned to house the cast of Thrupp’s effigy of Jane. She was laid beneath a stained-glass window based on her study of a Virgin and Child after Dürer, and the ceiling coved to suggest the vaulted roof of a tomb. Beneath it is the full text of Wordsworth’s sonnet ending: ‘A lovely beauty in a summer grave’.[2]

Notes

- William Blake, ‘Golden Age’, one of his engravings after John Flaxman’s illustrations to Compositions from the Works, Days, and Theogony of Hesiod, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, London, 1817.

- William Wordsworth, ‘Methought I Saw the Footsteps of a Throne’, 1806.

Nicholas Olsberg was Director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal and founding Head of Special Collections at the Getty Research Institute. He holds an honours degree in Modern History from Oxford University and a doctorate in Nineteenth Century history from the University of South Carolina. He has written books on the work of Herzog DeMeuron, Carlo Scarpa, John Lautner, Cliff May and Arthur Erickson, has been a columnist for the Architectural Review and Building Design and has contributed to the curatorial programme of Drawing Matter Collections since its inception.

In the second episode of series two of British Art Matters, Dr Christina Faraday speaks to Nicholas Olsberg about his insightful and comprehensive survey of Victorian architect William Butterfield.