Paul Rudolph: Transcending the Conventions of Architectural Drawing

Paul Rudolph (1918-1997) is known for his compelling large-scale presentation drawings, such as the memorable perspective sections of his Yale Art & Architecture Building in New Haven, CT (1958-1963), among others. But a deeper dig into the Rudolph archive at the United States Library of Congress in Washington D.C. reveals that there is more to his architectural imagery than what is familiar. Within the archive are drawings charged with energy, which push the boundaries of conventional presentation, capturing the bravado of Rudolph’s architecture. In this brief account, I will explicate three little-known but significant works which stood out for me during my long engagement with the archive. I met Rudolph and, with his agreement, looked at his papers during his final months in 1997. I helped organise his archive for the Library of Congress and used it to research my thesis, an exhibition, and eventually, the first scholarly, comprehensive monograph on Rudolph.[1] The three exciting discoveries I discuss in this short piece have not been exhibited since Rudolph’s death. They reveal unexpected dimensions to his methods and thinking, demonstrating how architectural drawing can be more than a rote exercise or simply factual.

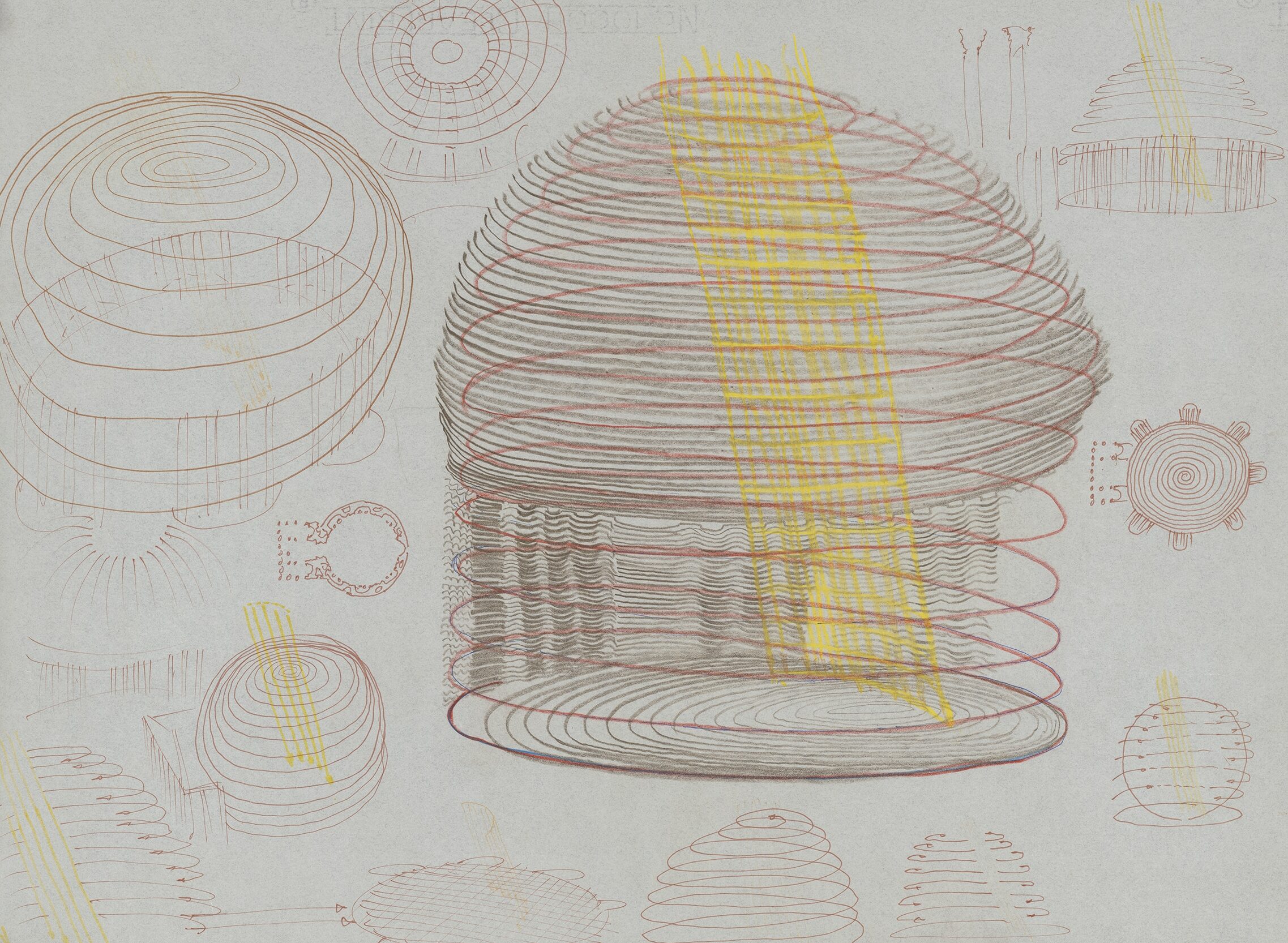

Energy and Light: Pantheon

Twentieth-century modernists are widely believed to have rejected architecture’s past, but that stereotype does not hold true for Rudolph. He expressed his deep appreciation for historical examples uniquely. His sketch of the Pantheon (Rome, 125 CE) showed that he understood canonical buildings differently, leaving behind familiar ways of representing them in static terms of elevation and plan to investigate them as manifestations of space, movement, energy, and light. Rudolph sketched the Pantheon as a rising series of rings of energy in colourful pencil and ink. The qualities usually depicted in most drawings of it—the materiality and structure of the temple—were not the concern here. At first glance, the image is almost unrecognisable as the Pantheon, instead appearing to be a glowing beehive ringed by smaller ones. A projecting beam of light from the oculus, rendered in yellow, shows that this was also a study of the way light falls. While the most familiar of Rudolph’s large-scale presentation and published drawings were in sombre pen and ink, the red, yellow, and brownish tones of this much smaller scale, undated sketch (46 x 61 cm) suggest it comes from the 1970s, when he began sketching in coloured pencil. Their hues give the Pantheon a warmth, making this familiar, stately monument seem like a sudden burst of movement, energy, and heat.

Endlessness: Temple Street Parking Garage

Another surprising image by Rudolph stretches its ground—its paper support—horizontally to depict a building seemingly without end. The Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven, CT (1958-63) resembled a Roman aqueduct and stretched across several blocks of the city, which urban renewal had ruthlessly demolished. By pushing it to extremes, Rudolph aggrandised a quotidian building type, the parking garage, which often disfigured cities. Rudolph wanted to bridge his garage across one of the new highways that charged through the old urban fabric to transform the garage into a monumental gateway into the city. His garage was something old—a triumphal arch or gateway—and something new: the birth of the megastructure. In its completed form, the garage was shortened, and it never bridged the highway.

However, Rudolph retained its seemingly endless and repeatable qualities in this memorable drawing, probably shown at the exhibition that accompanied the opening of his Yale Art & Architecture Building in 1963. It is for show and wonder more than for any practical purpose. It also registered his ambition at the high point of his career in the 1960s, when the possibilities seemed limitless for him and modern architecture. Can it be categorised as a drawing? It is not just a product of pencil or pen. The image could be considered a print. Rudolph liked to experiment with the technical production of architectural imagery. One garage bay was drawn, then reproduced and printed repeatedly with variations, thus cleverly highlighting the serial quality of the structure’s repeating arches. To understand its scale, I include this photo of myself unrolling it and my astonishment as it unfurled endlessly like a giant scroll. Recording a moment of discovery, I did not know when it would end as this photo was taken. There was almost no more room to examine it. It turned out to be 533 cm long![2] Unusually, this drawing occupied considerable physical space, like a building. This is practically an unheard-of quality for an architectural drawing.

Last Sketch: Wee Ee Chao Condominiums

A third drawing that demands attention is startling, arresting, and energetic to the point of making its subject seem angry, if a building can be such a thing. This is due to Rudolph’s startling use of red, a colour that often signifies energy, life, and aggression. A furious scrawl in pencil, this scribble depicts a building from Rudolph’s late production when most of his work was in Asia and receiving less acknowledgement than during his heyday, when his work was realised almost exclusively in the United States. His once-successful American practice declined markedly in the 1970s because of the fall of modernism around the same time and his own career missteps. Disappointed but fortunate, he found a more appreciative clientele in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Jakarta. In those comparatively quiet years, he channelled his intense energy into drawing. Rudolph’s astonishing sketch depicts a stacked condominium villa intended for the steep slopes that rise above Hong Kong. The structure is all platform and balcony to take advantage of views of the harbour. The red pencil glows, registering the energy of imagining and construction. Seemingly haphazard, it is an ungainly post and beam stack of exaggerated cantilevers. Never built, it is an ugly but powerful building and drawing.

The Library of Congress catalogue dates this drawing to 1994 when the design for the condominium began. From what I recall, this project had been shelved but had just come alive again in 1997. I believe I saw this drawing, or one like it, on Rudolph’s drawing board in his Manhattan townhouse—a structure somewhat like the one he was depicting—just before his death that July. I write this memory down here because such first-hand accounts often go unrecorded. Though declining, Rudolph worked on it furiously, until he had to take it to his deathbed. Poignant, the drawing emotionally registers his resistance to death itself and the final strokes of his genius—a word rarely used today that seems appropriate here.

In these ways and in these three drawings, Rudolph transcended the conventions of architectural drawing, taking it beyond the formulaic, and transforming it into a register of thinking and physical expression located in a place between the preciousness of art and the practicality of architecture.

Notes

- See the thesis: Timothy M. Rohan, Architecture in the Age of Alienation: Paul Rudolph’s Postwar Academic Buildings (Harvard University, 2001); the catalogue: Timothy M. Rohan, Model City: Buildings and Projects for Yale and New Haven by Paul Rudolph, Yale School of Architecture, Nov. 3, 2008 – Feb. 6, 2009 (New Haven: Yale School of Architecture, 2008); the monograph: Timothy M. Rohan, The Architecture of Paul Rudolph (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014, reprinted 2016 and 2021); the edited volume: Reassessing Rudolph, ed. by Timothy M. Rohan (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017).

- See the drawing: Paul Rudolph, Temple Street parking garage, New Haven, Connecticut. Elevation Rendering, 1959, 66 x 533 cm. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19124.

Timothy M. Rohan is associate professor and chair of the Department of the History of Art & Architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is the author of The Architecture of Paul Rudolph (2014) and edited, Reassessing Rudolph (2017). In 2008, he curated the exhibition Model City: Buildings and Projects for Yale and New Haven by Paul Rudolph in conjunction with the renovation of Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building. He is the author of numerous articles in the Journal of Architectural Historians, the Art Bulletin, the Architectural Review, Art in America and more.

The exhibition Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, curated by Abraham Thomas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, presents the full breadth of Rudolph’s contributions to architecture.

Download a PDF of Paul Rudolph’s ‘From Conception to Sketch to Rendering to Building’ found in Paul Rudolph Architectural Drawings (London: Lund Humphries, 1974), 6-14.