Drawing as Signature: Paul Rudolph and the Perspective Section

The following text delves into the drawing of the perspective section—a spatial and structural design tool as well as a specific type of architectural representation—through the drawings of Paul Rudolph, while also reflecting on a post-war Modern era of architectural design-thinking.

The text is included in Reassessing Rudolph, ed. by Timothy M. Rohan (New Haven: Yale School of Architecture and Yale University Press, 2017), 120–135.

The current exhibition Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, curated by Abraham Thomas, presents the full breadth of Rudolph’s contributions to architecture.

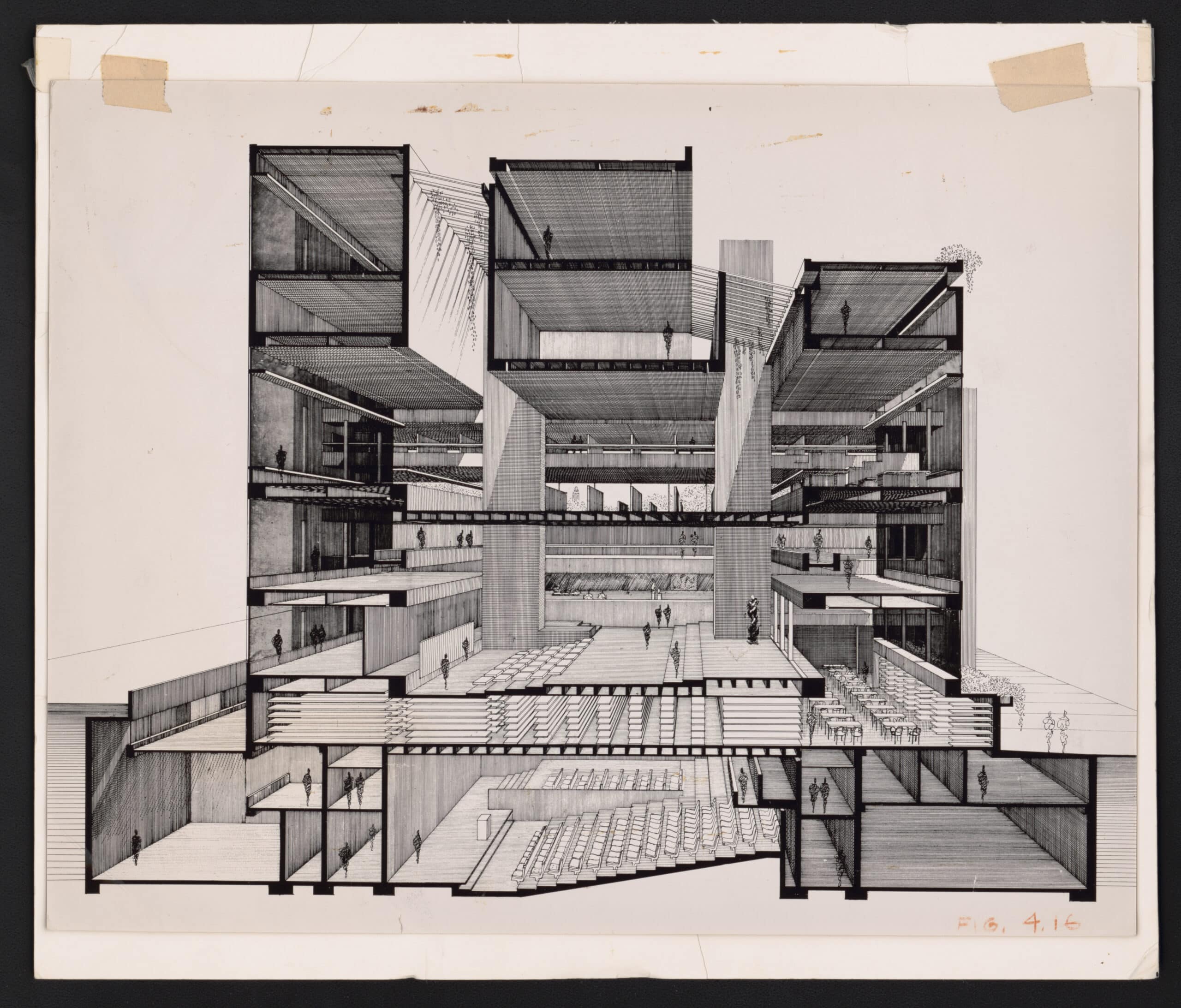

The perspective section is one of the most compelling types of architectural representation because it simultaneously reveals the structure of a building and its interior spaces. Though he certainly did not invent the perspective section, Paul Rudolph was its great populariser during the 1960s; it is nearly impossible to open an American, European, or Japanese architectural journal from that decade and well into the next without finding a section by Rudolph or one of his admirers. The perspective section of Rudolph’s most famed work, the Yale Art & Architecture Building (1958–1963), known as the A&A and renamed Rudolph Hall in 2008, is a striking depiction of spatial complexity executed in a labour-intensive manner, especially impressive today when rendering in ink is a thing of the past.

Such drawings showcased Rudolph’s draftsmanship, a skill he cultivated to make his reputation and for which he was much admired. Rudolph was regarded as a virtuoso for his design and drawing skills early in his career. Without blindly accepting such a characterization, identifying the attributes of Rudolph’s virtuosity helps in understanding that it was also something he consciously constructed or designed. The distinctive signature note of Rudolph’s draftsmanship was its many closely spaced parallel lines drawn by Rapidograph pen. They extend across almost every surface of the A&A Building rendering, signifying Rudolph’s complete mastery and control of his structure. The technique related to Rudolph’s other widely emulated architectural signature, the raised parallel ridges of the corrugated concrete walls he first developed for the A&A Building. Employed by him to the point where it became synonymous with him, the corrugated concrete treatment was his unique rendition of the béton brut, signifying Rudolph’s originality.

The perspective section is still another of Rudolph’s architectural signatures, the traits that his colleagues instantly associated with him, that gave him and his work a distinctive identity, and therefore helped advance his career, at least for a while. Rudolph often signed his drawings with a cursive signature, but it is nowhere nearly as distinctive as the perspective section, his Rapidograph linework, or his corrugated concrete. These signatures should be taken into account when reconsidering Rudolph’s architecture because they help in understanding him, his buildings, and their relationship to postwar architecture and society.

Rudolph explained the section’s significance for him in a 1986 interview, ‘The section is as important, or more important, for me than the plan. That is because it does depict the space, it does depict the light in ways in which the plan alone does not do. I don’t mean to say not to have a plan, but I do mean to say you must have a section.’[1] Architects have recently recognized how the section enriches the design process and have acknowledged Rudolph’s skilful employment of this drawing type.[2]

In contrast to the quickly dashed-off sketch often regarded as the origin of a building, Rudolph’s highly finished perspective sections are midterm statements usually made near the end of the design process, but before completion of the building. They had many functions. Produced for publication to bring attention to Rudolph’s architecture, enhance his reputation, and garner more commissions, they were compelling drawings legible to both architects and a broader public unfamiliar with architectural representation. At the same time, they helped Rudolph understand his complex spaces and how they might affect users. Ideological as well, the perspective section also registered Rudolph’s partisan views about Modern architecture. Shading, the careful depiction of shadows, and use of perspective attest to Rudolph’s desire to control space and light in order to produce a subjective, expressive, and emotional architecture that would be an alternative to the seemingly objective and rational functionalism of the 1940s in which he was trained, and the International Style, which he frequently criticized in the 1950s.

While certainly egotistical, Rudolph’s stress upon subjectivity was not his alone, but part of a broader tendency in postwar architecture that sought to ‘humanise’ Modernism by focusing it upon the subjective qualities of the human body, mind, and emotions. One of the architect’s most compelling signature traits, the perspective section can be used to trace the development of interior space in Rudolph’s architecture and to explore the problems inherent in his attempts to make an architecture that would affect the psychology of its users.

Searching for a Distinctive Technique

Architectural drawing follows well-established conventions that would seem to allow little room for personal expression. And yet, Rudolph saw the medium as a means for expressing his ideas about architecture. The places where Rudolph trained acknowledged his skill at drawing from early on, but did not encourage practicing it as an expression of individuality, nor did they particularly endorse the perspective section. In the late 1930s, Rudolph received a conventional Beaux-Arts undergraduate education at Alabama Polytechnic (now Auburn University); helped architect Ralph Twitchell design Modernist houses in Sarasota, Florida, during a ‘gap year’; and matriculated at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) in fall 1941.

When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, Rudolph and most of his classmates joined the armed services. He enlisted in the Navy, took a maritime architecture course at MIT, and became a lieutenant supervising ship repair in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for the war’s duration. Rudolph later said that those years were a time when ‘. . . I searched for a technique of drawing which would allow my personal vision to be suggested . . .’[3] The statement typifies how Rudolph used drawing to prove and produce evidence of his creativity, originality, and individuality, thus mythologizing these carefully constructed character traits, while giving very little credit to actual events or experiences that may have shaped his development.

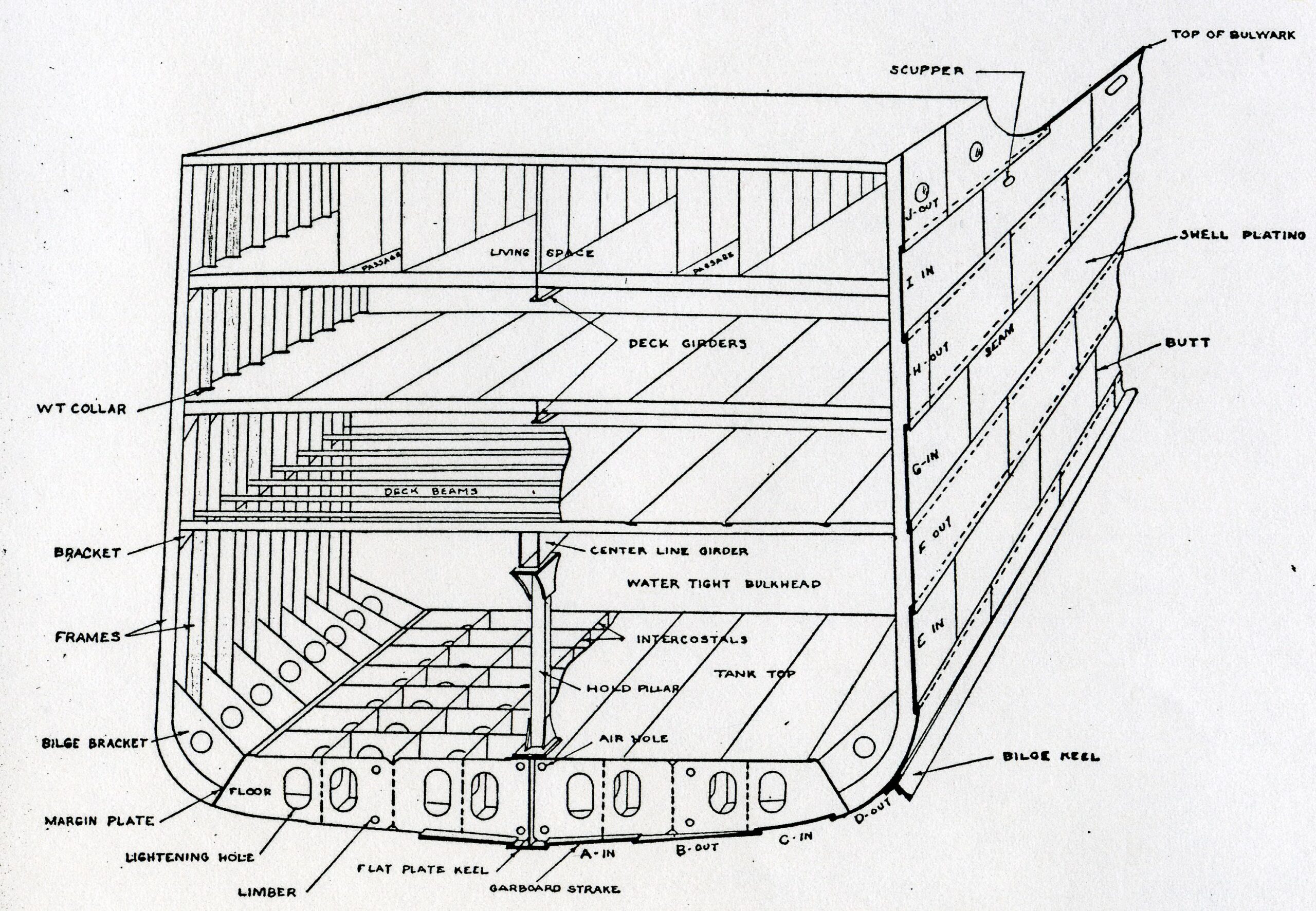

One educational experience of this time that may have alerted Rudolph to the perspective section’s potential was the course in maritime architecture he took at MIT. Textbooks in the discipline from this period often used the perspective section to explain the internal organization of ships. These drawings explained space, structure, and materials using just one image in a manner more economical and quicker for the eye to absorb, especially for large structures, than typical architectural representation, with its many plans and elevations.[4] For Rudolph, perspective sections of ships would also have been appealing and familiar because of their regular appearances in the mass media. The perspective section was regularly used to explain the wondrous complexities of ocean liner interiors in advertising posters and in magazines, such as Popular Science. Ships and their imagery had also long appealed to the Modernist sensibility. Le Corbusier, of course, famously appropriated an ocean liner section to help explain the interior workings of his Unité d’Habitation (Marseilles, France, 1946–1952).

The Harvard Box

After World War II ended, Rudolph was more eager to work than to complete his Harvard degree. He rejoined Twitchell’s small firm in Sarasota, Florida, where vacationers were open to building Modernist holiday houses. While Twitchell secured clients and supervised construction, Rudolph concentrated on design, at first almost single-handedly producing all of the firm’s drawings for building and publication in a manner notable for strong graphic and expressive qualities that conveyed the distinct contrast between sunlight and shadow in Florida. Rudolph returned to Harvard in 1947 where special consideration for veterans made it possible to complete his coursework and master’s degree in only one semester.

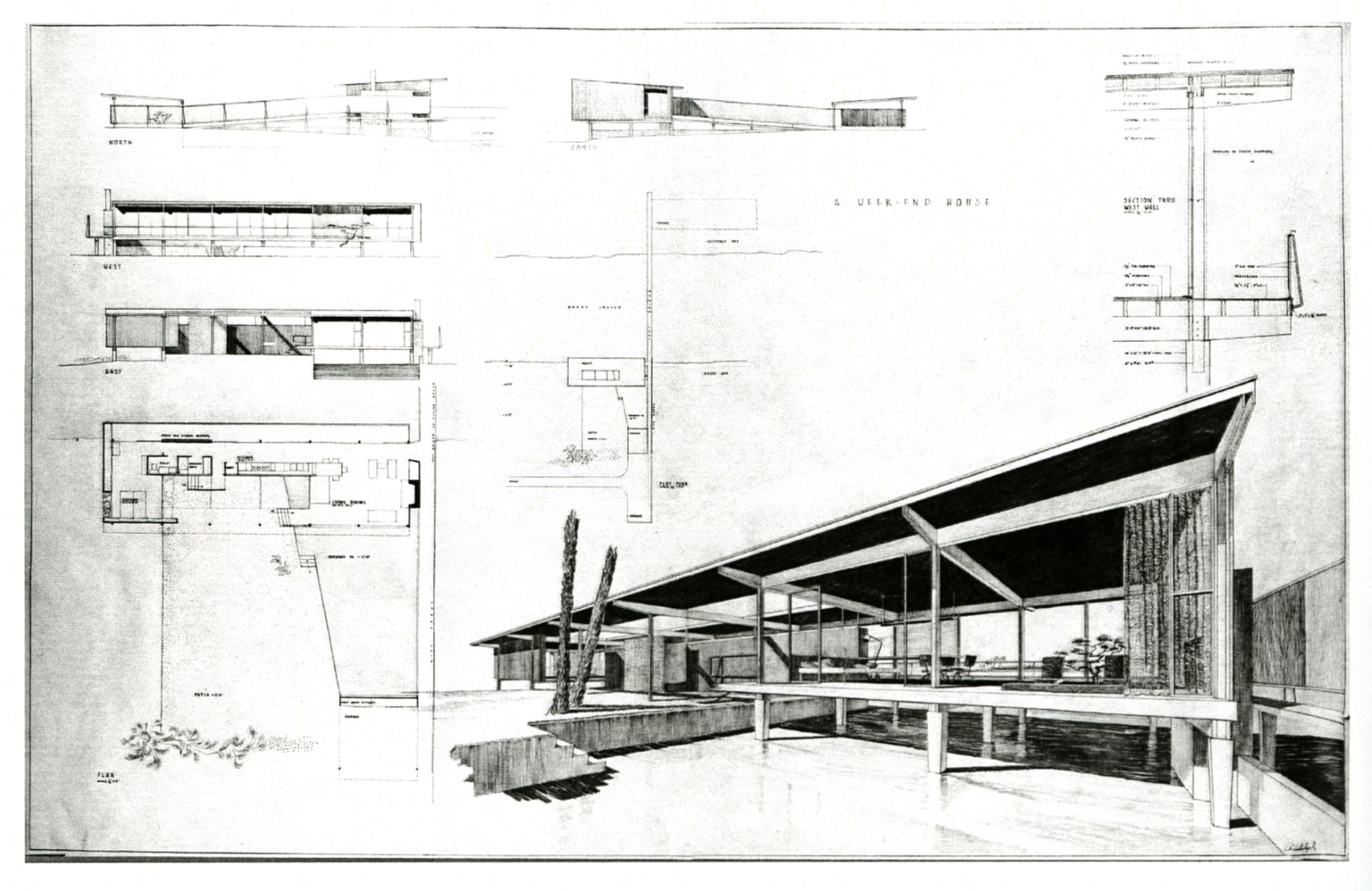

One of Rudolph’s GSD studio projects from 1947, a small, flat-roofed, rectangular, one-story ‘weekend house for an architect’ shows how he accepted and yet questioned what he learned at Harvard. He situated it in Sarasota, and later revised it. Rudolph’s project for a rectangular house exemplified the ‘Harvard Box,’ a term students used to disparage the rote functionalist solutions favoured by their instructors.[5] No matter what the program called for, the rectangular box was always the solution. A powerful force during the interwar years in Europe, functionalism emphasized the objective over the subjective and expressive, but many felt it had degenerated and become inhibiting as it was practiced in American architecture schools during the postwar years.[6] Gropius and colleagues close to him at the GSD stressed the functionalist approach in their teaching, emphasizing objectivity, science-based approaches, and teamwork, while discouraging overt expressions of individuality.

The Harvard Box was mandatory, even for Rudolph. But he enlivened his ‘weekend-house’ rendition by departing from the typically utilitarian means of representation practiced at the GSD. Rudolph drew a skewed perspective view of his weekend house to reveal how it nearly floated above an artificial inlet. Showing that it was more than just a functional container, Rudolph nimbly engaged the house with the alternatingly dry, wet, and spongy Florida terrain under it, offering boats and inhabitants numerous opportunities to move between the structure and the water beneath it. Seen side-by-side, the perspective view is certainly more revealing and compelling than the accompanying diagram-like plans and elevations of the house. It suggests the increasingly expressive direction Rudolph’s imagery and architecture would take over the next few years.

Opening up the Box

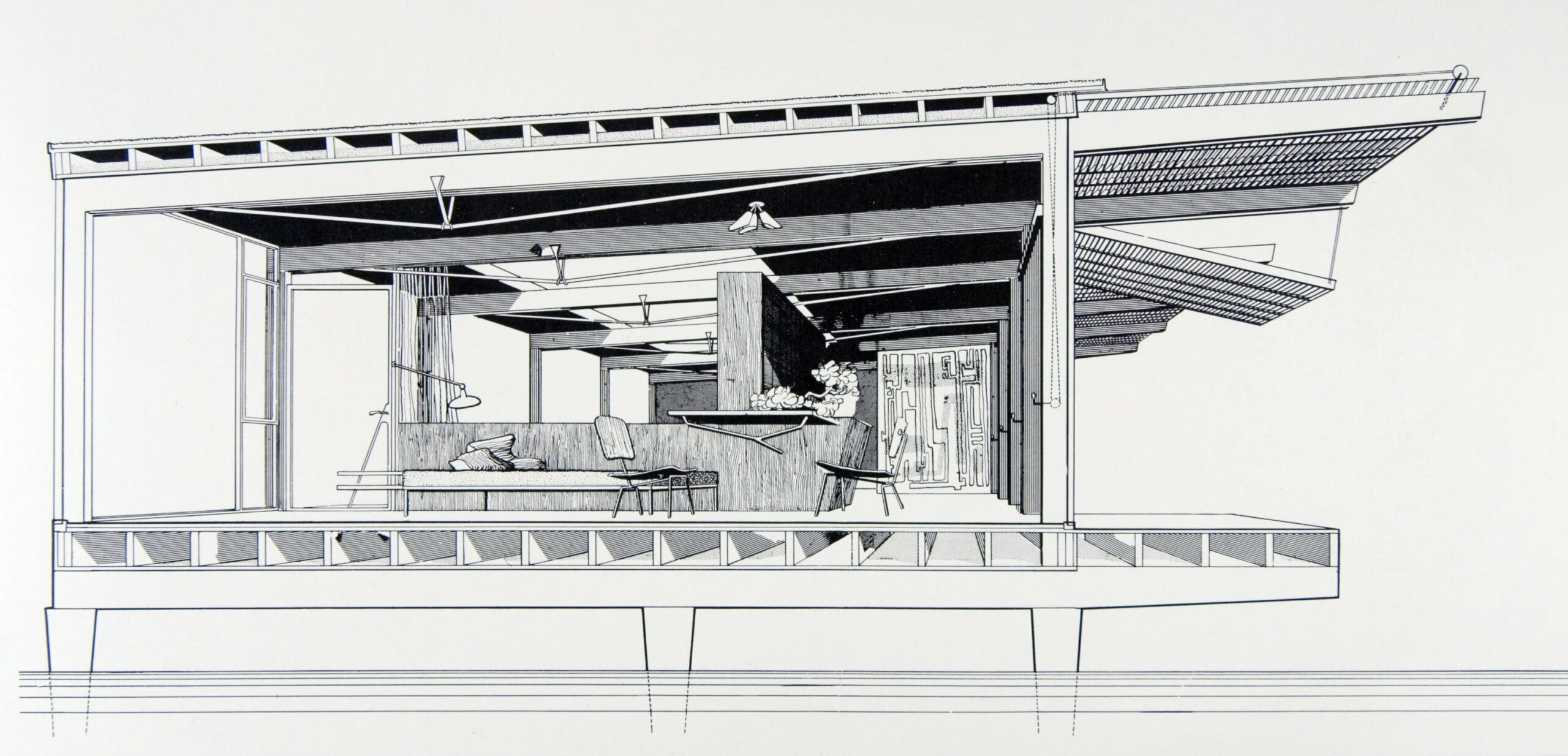

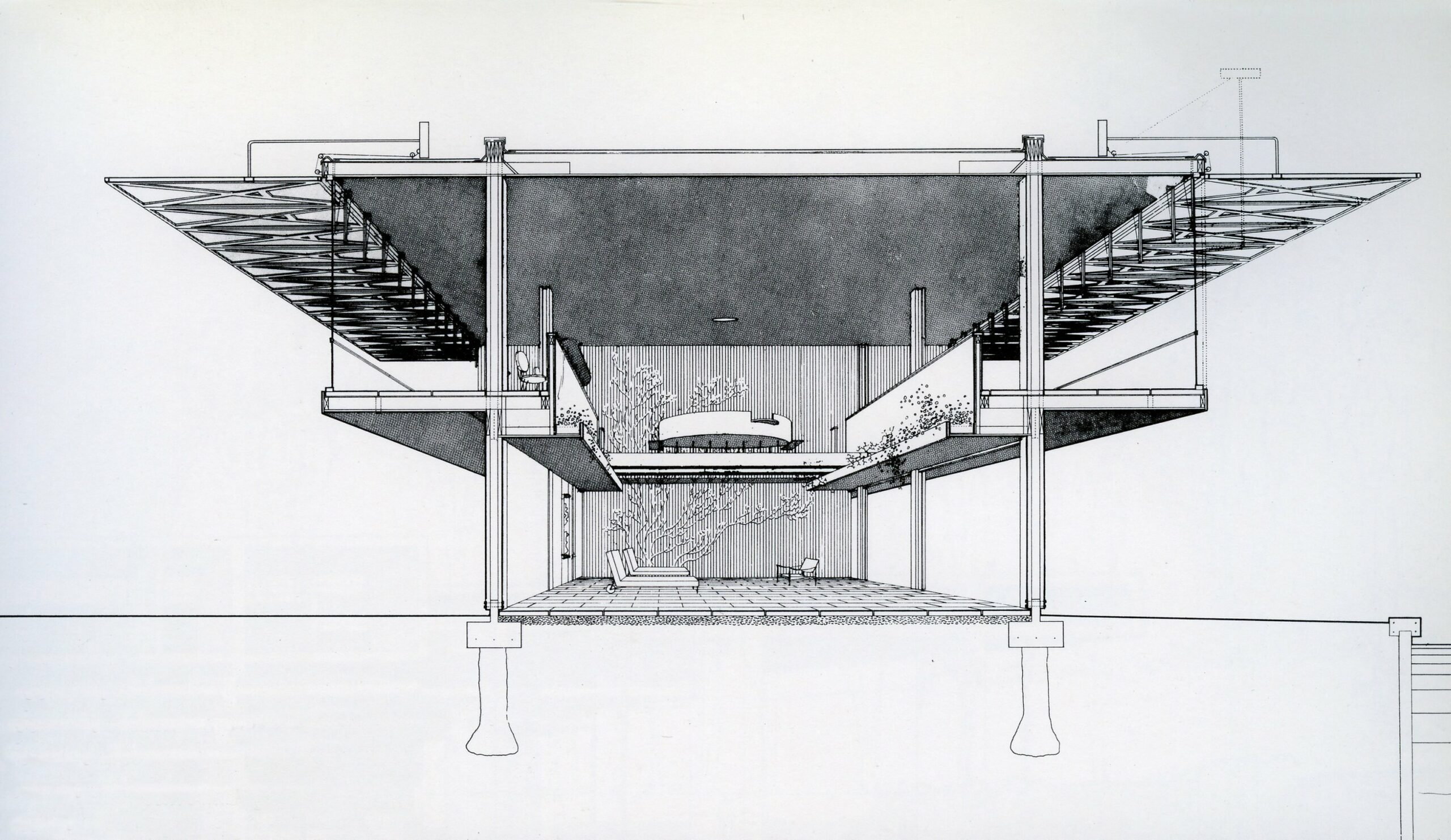

The Harvard weekend-house project of 1947 remained important for Rudolph. That same year, he revised it as a guest house for Mrs. Roberta Healy Finney (unbuilt project, Siesta Key, Florida, 1947). The Finney House became a model for his Florida houses and a vehicle for his experiments with architectural representation. Rudolph’s first known published use of the perspective section occurred when the Finney project appeared in Interiors magazine in 1950. For this section, Rudolph depicted a cut taken through the portion of the house raised above the inlet. The section could almost be mistaken for a depiction of a ship, barge, or dock rather than a conventional house.

The house itself changed little from the original Harvard project, but the introduction of the section confirmed Rudolph’s turn away from objectivity and functionalism. Its presence indicates a desire to engage the viewer, causing him or her to empathize with the building—or at least the image—in some way. While the functionalist plans and diagrams of the GSD imparted information in a matter of fact, objective manner, the perspective section rendered through the relatively simple means of one-point perspective very quickly pulls the eye of the viewer along the receding orthogonals, inwards and deep into the image. In this way, it helps the viewer to insert him or herself into the space, rather than distancing the viewer, as did the plan—a type of representation that requires an eye accustomed to the symbolism of its dashes signifying hidden beams, arcs denoting an opening door, or other such notations. It takes longer to read a plan than a perspective section. By following the receding orthogonal lines of the section, the viewer also experiences the house through Rudolph’s viewpoint or subjectivity. Though they do not always realize it, viewers have similar experiences when watching films made by expert cinematographers.

Understanding that print media could help advance his career greatly, Rudolph crafted images for publication, like the perspective section, which were legible and eye-catching in order to appeal to prospective clients, fellow architects, and others. Wide-circulation magazines, such as Vogue and House & Garden, published Rudolph’s Florida houses frequently, with inviting photographs by Ezra Stoller in which carefully selected objects, such as lounge chairs and sunglasses, evoked postwar leisure.

After leaving Twitchell to establish his own Sarasota office in 1952, Rudolph’s work became more experimental, and he turned to the perspective section more frequently in order to explain projects with increasingly complex interiors. In his award-winning, unbuilt project for the Cohen Residence of 1952–1953 (Siesta Key, Florida), for example, a circular conversation platform floats in the middle of the double-height space at the centre of the house. In this section, it is evident how Rudolph considers the vertical dimension as much as the horizontal dimension, which the plan always emphasizes. This double-height space in the Cohen House is actually a screened area, like a giant porch, a porous space open to cooling breezes and the elements. Suggestive of new dimensions for Rudolph’s architecture, it is ambiguously between indoors and outdoors. Ringed by balconies, it is also a prototype for similarly configured rooms in future buildings by Rudolph.

Once again, this image seems more like the depiction of a ship than a conventional house; the ground floor is almost flush with the watery surface of an adjacent canal visible on the far right. In just one example of how widely Rudolph’s imagery circulated, drawings of the Cohen Residence appeared in several different American and European architectural journals during the 1950s, ranging from California Arts and Architecture and L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui to Progressive Architecture, which gave the house one of its yearly design awards in 1954.[7]

Humanizing Modernism

Rudolph’s increasing use of the section coincides with his emergence in the mid-1950s as an outspoken critic of the postwar International Style who sought to create a more expressive architecture. A key word for the period, ‘expression,’ was employed by those who sought to temper Modernist abstraction with human emotions, resulting in an art and architecture based upon subjectivity, as in ‘Abstract Expressionism.’ Rudolph explained his standpoint in a series of well-received talks and articles during the 1950s. Decrying the current state of architecture, Rudolph said in 1954, ‘Modern architecture’s range of expression is today from A to B.[8] In a direct rejoinder to the evenly illuminated and exposed glass curtain-walled buildings and interior spaces of the International Style, Rudolph wrote in 1957, ‘We need caves as well as gold-fish bowls.’[9] This disarmingly simple dictum calling for a juxtaposition of opaque, darkened, enclosed spaces with transparent, bright, open ones became a basic precept for Rudolph’s concept of interior spaces. The perspective section was the ideal means by which to represent these spatial juxtapositions and complex effects of light and shadow, and to consider how humans might react to them.

At the 1954 national conference of the American Institute of Architects, Rudolph called for spaces invested with ‘human’ qualities which would strongly affect the body and the mind in a subjective way, ‘We need sequences of space which arouse one’s curiosity, give a sense of anticipation, which beckon and impel us to rush forward to find that releasing space which dominates, which climaxes and acts as a magnet, and gives direction.’[10] In Rudolph’s description, spaces stimulate human moods and movement. Such positivist thinking reflected the particular thread of discourse about architectural ‘humanism’ in the twentieth century that dated back to Geoffrey Scott’s explanation of Renaissance architecture in his book, The Architecture of Humanism (1914), which achieved a new popularity in the 1950s.[11] Scott maintained that the humanism of Renaissance architecture was directly inspired by the human body, its emotions, and the genius of its individual designers, rather than functional requirements. Scott’s thinking appealed to those like Rudolph, Eero Saarinen, and Philip Johnson who were intent on developing a dynamic architecture of form instead of function.[12] It would be expressive of their economically and politically powerful society.

Rudolph encountered other colleagues who admired Scott and thought similarly about architecture when he became a visiting critic at Yale in 1956. Architectural historian Vincent Scully used Scott to explain the ethos of architecture in late-1950s America, as the limitations imposed by functionalism and the International Style gave way to the ‘liberated and enriched’ historically based forms of Saarinen, Johnson, and even Louis Kahn. Scully quoted Scott to define the body-centred, humanist architecture he advocated for an energetic postwar America, whose origins lay in Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. To describe Sullivan’s buildings, Scully used this quote from the concluding chapter of Scott’s book, where he said of Renaissance architecture, ‘The centre of that architecture was the human body: its method, to transcribe in stone the body’s favourable states; and the moods of the spirit took visible shape along its borders, power and laughter, strength and terror and calm.’[13]

All that Rudolph hoped that his architecture could achieve is expressed in these words. Rudolph took them to mean that the building should be a register of his own psychology, subjectivity, viewpoint, or genius, just like his perspective section drawings. His was the human body in Scott’s description. But, as will be shown, there was a considerable difference between asking someone to see a building through Rudolph’s viewpoint as expressed through a perspective section and asking them to use or inhabit a building so closely determined by his point of view.

Yale A&A

At the age of 39, in 1958, Rudolph reached the apogee of his career when he became the chairman of the Department of Architecture at Yale. His practice shifted toward the making of large-scale civic and academic buildings for a prosperous, powerful postwar America. He turned to the perspective section more frequently to explain their complexity. At this time, other architects also turned to the perspective section to explain the new generation of spatially complex, institutional buildings in concrete, which became known as Brutalism. Kallmann, McKinnell and Knowles memorably employed the perspective section to depict the interior spaces and structure of their famed Boston City Hall (1961–1968). Hazily rendered, compared to the hard lines of Rudolph’s sections, the drawing was from a set of published renderings executed by the firm. Their atmospheric qualities softened the visual impact of the building’s massive concrete forms for an architectural community and public still unsure about such monumentality.[14]

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Rudolph rarely used professional renderers, preferring to produce drawings that truly represented his point of view. In his New Haven office, with the assistance of a staff of about ten full-time architects, Rudolph supervised the making of numerous drawings for presentation to clients and for publication. He received much help from skilled employees such as the British architect John Fowler, who well understood but questioned Rudolph’s employment of the section, as shall be shown.[15] Despite his busy daily routine, making presentation drawings remained important to Rudolph. He was often intimately involved in making ones for his projects, frequently altering them when they were in production and executing some of his signature repetitive linework himself, a skill at which he excelled.

Rudolph also employed students from the Department of Architecture to execute the labour-intensive linework with the Rapidograph pen, such as Charles Gwathmey. The experience related to what they learned in Rudolph’s Yale studios. He always required students to feature perspective sections in their final presentations. As a result, some, such as Norman Foster, one of Rudolph’s most renowned students, frequently employed the perspective section to depict their own buildings. Foster later acknowledged that his teacher’s imagery made a lifelong impression upon him.[16] By his published examples, Rudolph popularized the perspective section amongst architects during the 1960s, and drawings similar to his from across the world could be found in journals published from Japan to Germany. Following Rudolph’s lead, professional architectural renderers of the late-twentieth century also popularized the perspective section, such as Paul Stevenson Oles, who was a Rudolph student from Yale.[17]

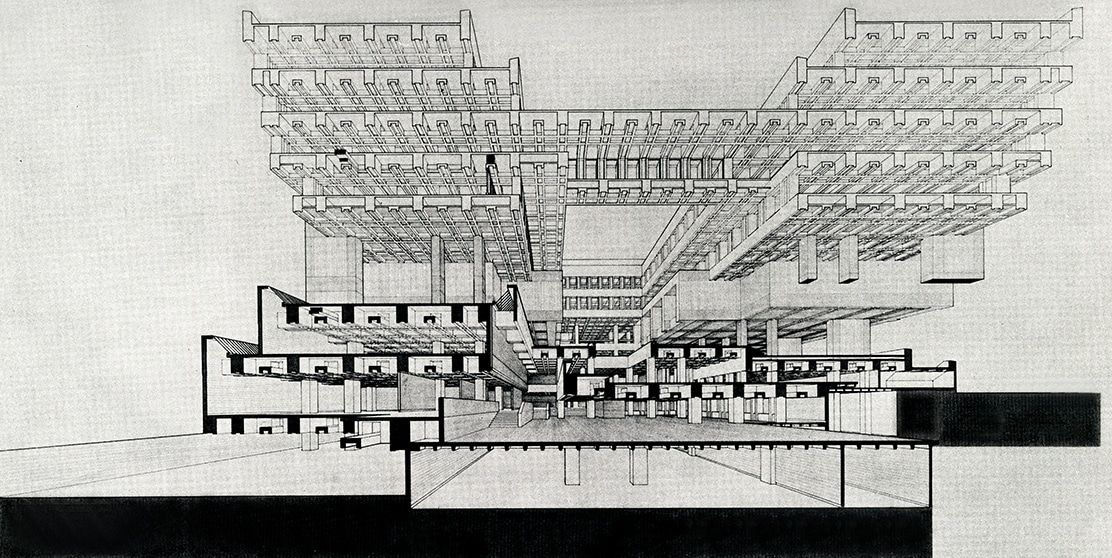

Soon after arriving at the University, Rudolph received the commission that would bring to fruition his experiments with the manipulation of interior space in order to stimulate psychological reactions. The Yale Art & Architecture Building (1958–1963) was intended to bring the various programs of the school together under one roof, including studio art, architecture, urban design, and the art history library.

The most striking image of its kind that he produced, Rudolph’s widely published perspective section of the A&A Building depicted the complex interior with just one view that could be seen in a single glance.[18] The drawing explained how the auditorium, library, exhibition gallery, and studio spaces were stacked on top of one another to take advantage of a constricted urban site. In a way that would have been difficult to illustrate even with many plans, the single drawing dramatically illustrated how the thirty-seven different levels of the building ranged from darkened ‘caves,’ like the basement auditorium, to dramatic ‘gold-fish bowls,’ like the double-height drafting room. Exemplifying his volumetric approach to design, it demonstrates how Rudolph emphasized the vertical as much as the horizontal dimension in his architecture. Ringed by balconies, these double-height rooms are the fulfilment of the prototype suggested by the perspective section of Rudolph’s unbuilt Cohen House. The perspective section shows how the rooms related to one another. Both in the drawing and as actually achieved in the built structure, the chambers are connected visually by long diagonal vistas, making it possible to see through the body of the building—thus linking different activities and functions together: from designing, to exhibiting works, to library research—and outside to the city streets, reminding students of the importance of the urban context, something Rudolph emphasized in his teaching. Despite the heaviness of the concrete walls, there is flexibility here, suggestive of dialogues between the inhabitants and the multiple ways in which the interiors related to one another and the campus and city.

In keeping with his thinking about how light and shadow affected emotions, Rudolph used the perspective section to depict how sunlight penetrated deep into the building through multilevel shafts topped by skylights. He showed how the A&A’s corrugated concrete walls cast shifting plays of light and shadow, represented by cross-hatching and many parallel vertical lines. Rudolph later hinted at how his signature linework might have inspired the corrugated concrete treatment of the walls.[19] The contrast between light and shadow gave the drawing a sombre quality, imparting a sense of atmosphere and emotion.

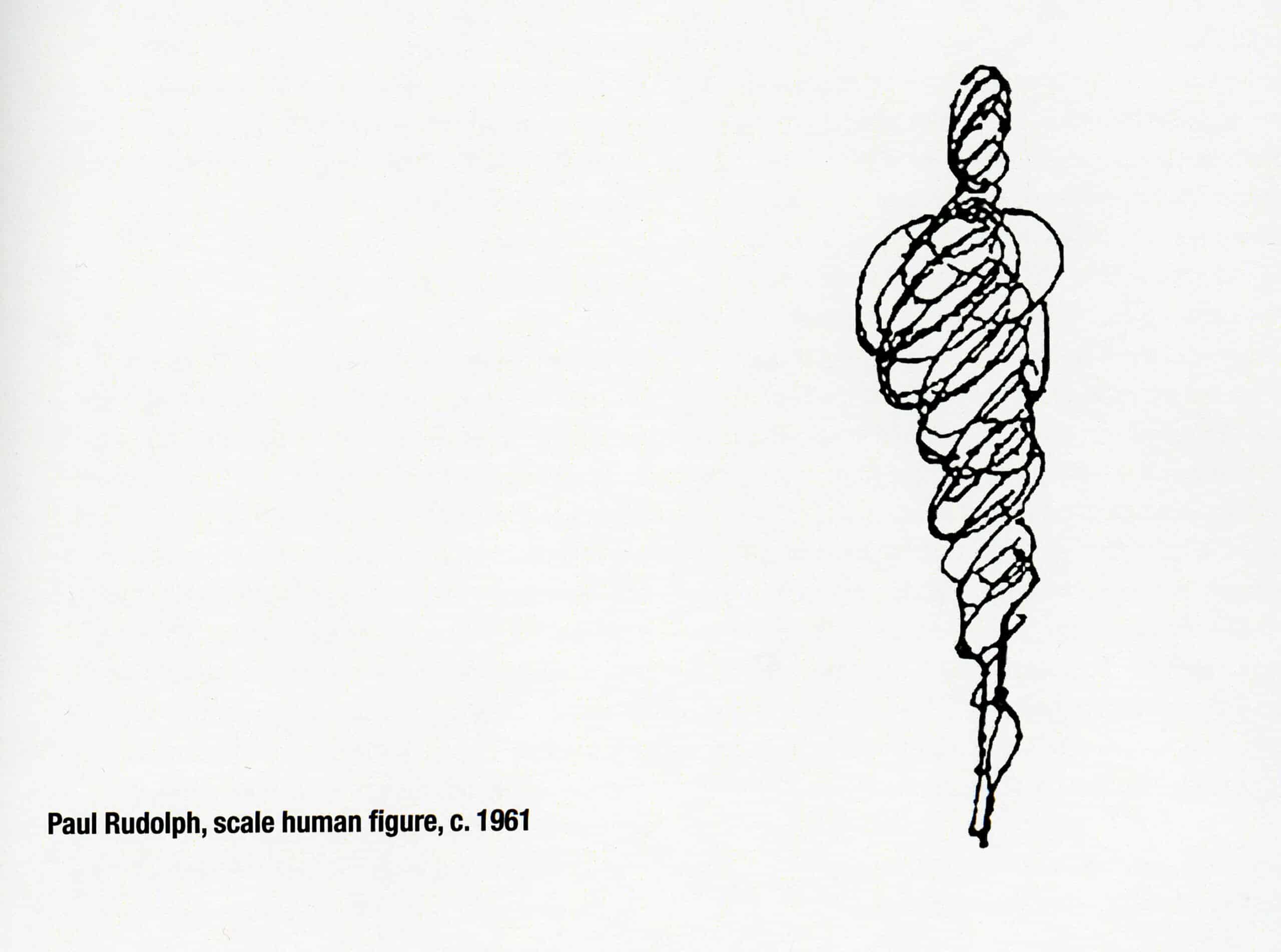

In what became still another of his signature touches, Rudolph himself drew the distinctive spiralling human figures which populate the drawing to illustrate scale and to show how he imagined the building affecting the inhabitants. As quickly drawn as a doodle, each figure is a register of the immediate energy of Rudolph’s hand as the pen touches paper. Each maintains its balance on just one tiny point amidst the building’s many levels, platforms, and chasms, buffeted by the waves of emotion Rudolph imagines the building emitting.Further evidence of how Rudolph thought that buildings affected the body and mind appears in colourful sketches he began producing of his own buildings in the 1960s, culminating many years later in a series analysing the plan of Mies van der Rohe’s German or Barcelona Pavilion (Barcelona, Spain, 1929; reconstructed, 1986). Freely rendered compared to the perspective section’s standardized format, Rudolph attempted in these studies to analyse movement, light and even reflections by drawing irregular lines in coloured pencil, their different hues suggesting varying degrees of intensity.

Not long after the A&A Building was completed to almost universal acclaim, John Fowler wrote a trenchant review of it suggesting that his employer had become overly reliant upon the perspective section. Fowler thought the section had driven the composition of the building almost as much as the program. He wrote, ‘Rudolph works very quickly, almost impetuously. His architecture becomes a process of assembling incidents of “excitement.” His excellent drawings perform the function of bringing these together. Conceivably there is no other contemporary architect who relies on perspective drawings as he does, and his buildings even begin to acquire their characteristics.’[20] Rudolph believed he could articulate his subjectivity as a designer through the perspective section, but he may have become overly reliant upon it, just as his GSD instructors had relied too often upon the ‘Harvard Box.’ Architectural drawing, speech, and handwriting are established conventions that to some degree define the thinking of designers, speakers, and writers as much as they articulate their utterances; this is true too of today’s designers who use software they did not program to design their buildings. Does the perspective section reveal anything really personal about Rudolph, or did it become for him a rote and formalist manipulation of conventions?

Reflecting the viewpoint of fellow Britons who thought that ethics should outweigh aesthetics—namely Reyner Banham—Fowler concluded that the A&A Building was a superficial answer to the problem of creating such a complex building.[21] For Fowler, the building was an overly grandiose, formalist exercise that neglected basic functional needs. Rudolph’s repeated use of the section was a symptom of his increasing formalism, a problem for Rudolph and all of postwar Modernism.

Published in spring 1964, Fowler’s review reflected growing disenchantment at Yale with the A&A and Rudolph. The students and many faculty found Rudolph’s ‘gold-fish bowls’ too hot and too bright, his caves dark and claustrophobic rather than comforting, and the complex relationships between his spaces bewildering. The building was about him, not them. Their growing discontent challenged Rudolph’s authority at Yale, one of several factors that led him to resign by 1965 to pursue what he anticipated would be a flourishing practice in Manhattan. This was not to be. By the mid-1970s, Rudolph experienced an almost complete reversal of fortune: fire gutted his Yale A&A Building in 1969, his Modernism became the target of postmodernist critiques, and a troubled economy caused commissions to fall off for the type of large-scale, publicly funded institutional buildings in concrete that had become his specialty.

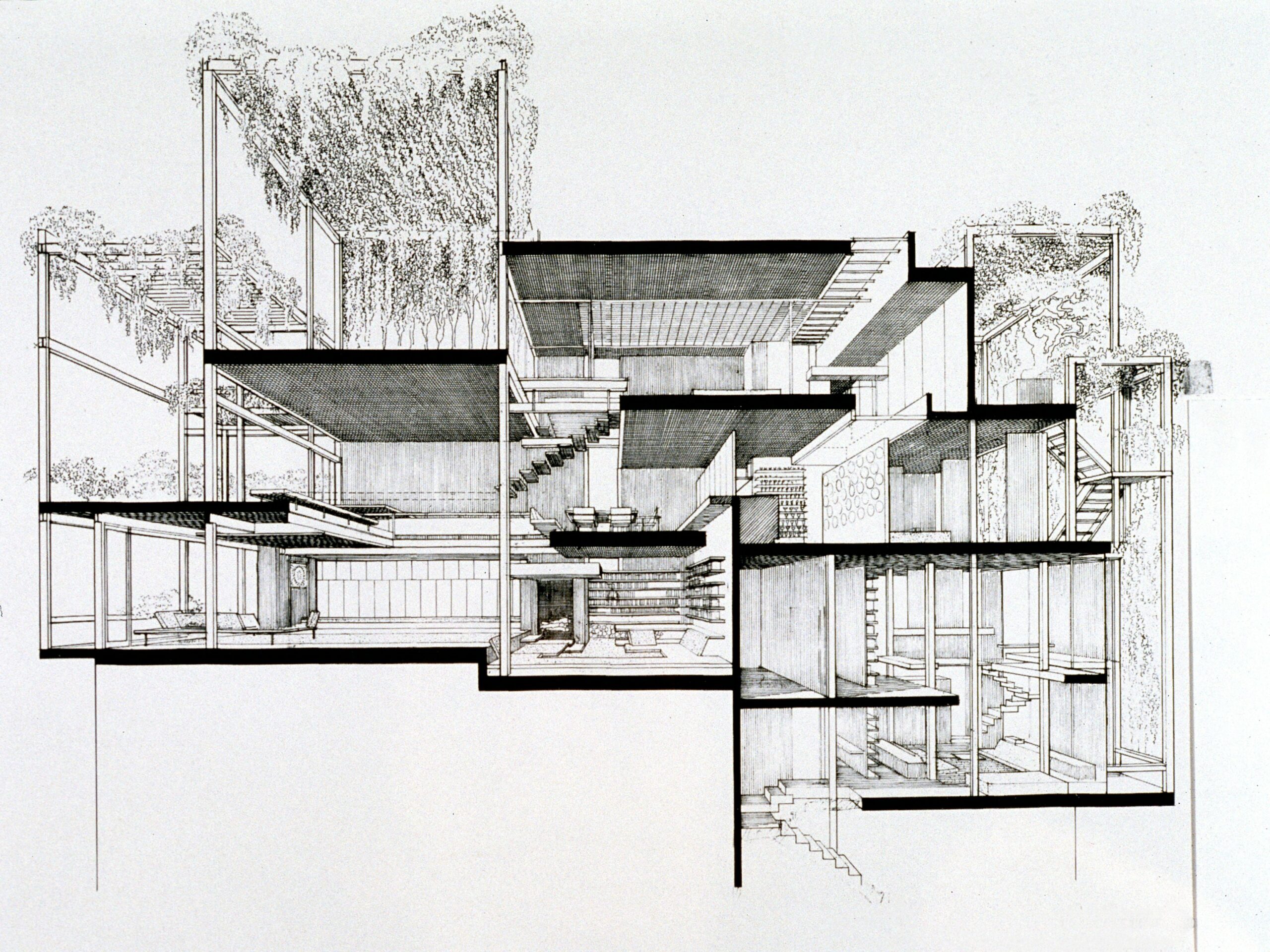

Reckoning with the Rendering

Withdrawing from architectural discourse as his reputation declined, Rudolph turned inwards during the 1970s. He still made complex, compelling drawings, some of which attest to the almost completely interior turn that he took both personally and professionally. The perspective section of his remarkable Manhattan penthouse (1988) depicts a fantastically intricate array of caves, gold-fish bowls, double-height rooms, and terraces linked by staircases and transparent, Plexiglas bridges. Carrying the qualities of the section into the actual, built penthouse, these Plexiglas bridges functioned like cuts in the floors which made it possible to peer through the body of the house, seeing the different levels below as though looking into a perspective section. The penthouse is the work by Rudolph where the drawing and the completed building bear the closest resemblance to one another. The built penthouse expressed Rudolph’s own subjectivity, but it also stimulated an entire range of varied reactions from those who encountered it that Rudolph could not anticipate or control. Rudolph’s architecture makes situations that produce multiple unpredictable, emotional reactions. His penthouse captivated some, and disconcerted others. Rudolph enjoyed drily recounting how the penthouse’s Plexiglas bridges caused a visitor susceptible to vertigo to faint.[22]

Such an anecdote might lead one to conclude that Rudolph remained unaware or heedless of how buildings formulated from his viewpoint affected users other than himself. Rudolph was, in fact, cognizant by this time of the limitations of his design methods, especially his reliance upon drawings. He knew that his drawings could not anticipate the reactions of users. In his 1972 monograph of drawings published at a troubled period for him of self-doubt and reflection, just three years after the immolation of his A&A Building and on the eve of the postmodernism that would soon take him to task, he mused ruefully about the complicated relationship between architecture, its image, and its reception, ‘The psychological impact of the architect’s design will not be truly known until it is built and, even then, its meaning will vary for individuals and will also vary with the passage of time. Renderings seldom convey the psychological meaning, the building’s true essence.’[23]

Rudolph’s many signatures—the parallel line work, the corrugated concrete, the perspective sections, and the wiry human figures which populate them—helped promote his carefully constructed genius, but they also became registers of his agony (itself a quality often seen as characteristic of genius) about making architecture. These signatures also reveal the greater dilemmas of postwar Modernism’s attempts to humanize itself by emphasizing individuality, creativity, and emotion. Despite their strong physical presence and many signature notes, Rudolph and his architecture are not the stable, knowable subjects they might initially seem to be. Tracing the perspective section through Rudolph’s work provokes questions about making, looking, inhabiting, and feeling that raise discussions about him and his architecture to the ontological level.

Notes

- Paul Rudolph, ‘Excerpts from a Conversation,’ Perspecta, 22 (1986), 103.

- Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki, David J. Lewis, Manual of Section (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016).

- Rudolph, ‘From Conception to Sketch to Rendering to Building,’ Paul Rudolph Drawings (Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita Tokyo Co., Ltd., 1972), 11.

- For a history of the relationship between maritime architecture and the architectural section focusing on seventeenth-century French practices, see Jacques Guillerme and Hélène Vérin. ‘The Archaeology of the Section,’ Perspecta 7 (1989): 226–57. Introductory textbooks on maritime architecture stressed the section. For two from the WWII period, see C.O. Liljegren, Naval Architecture as Art and Science (New York: Cornell Maritime Press, 1943), 5–12. And George C. Manning, Manual of Ship Construction (New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1942).

- For GSD pedagogy, see Jill Pearlman, Inventing American Modernism: Joseph Hudnut, Walter Gropius, and the Bauhaus Legacy at Harvard, (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2007). Also see, Anthony Alofsin, Struggle for Modernism: Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and City Planning at Harvard (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002). Klaus Herdeg famously critiques the ‘Harvard Box’ in his polemical book, The Decorated Diagram: Harvard Architecture and the Failure of the Bauhaus Legacy (Boston: MIT Press, 1983).

- Box-like solutions were endemic to American architecture schools in the 1940s and 1950s. In New Haven, students turned out Miesian-inflected ‘Yale Boxes,’ see Robert A.M. Stern and Jimmy Stamp, Pedagogy and Place: 100 Years of Architecture Education at Yale (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016), 115.

- For the Cohen House, see ‘House by Paul Rudolph,’ California Arts and Architecture, vol. 71 (September 1954): 14–15 and ‘Quatre Habitations en Floride, USA’, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, vol. 26 (November 1955), 34–35. The 1953 project won the Progressive Architecture Awards of 1954, ‘First Design Award: House, Siesta Key, Florida,’ Progressive Architecture, vol. 36 (January 1955), 6–67. Though it was a prize-winner, Rudolph built an entirely different project for the Cohen House in 1955. For images and an account of these different versions of the house, see Joseph King and Christopher Domin, Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002), 173–77.

- Rudolph. ‘The Changing Philosophy of Architecture,’ The Architectural Forum 101 (July 1954), 120

- Rudolph, ‘Regionalism in Architecture,’ Perspecta 4 (1957), 16.

- Rudolph. ‘The Changing Philosophy of Architecture,’ 120.

- Geoffrey Scott, The Architecture of Humanism: A Study in the History of Taste, with an introduction by Henry Hope Reed Jr. (London: Constable and Company, 1914, 1999 edition). Rudolph quotes Scott in his article, ‘The Six Determinants of Architectural Form,’ Architectural Record, vol. 120 (October 1956), 186. Rudolph notes the book as an important influence in ‘Paul Rudolph: Drawings,’ Architectural Forum (June 1973), 51.

- Philip Johnson said Scott’s The Architecture of Humanism was a ‘bible’ for him. Philip Johnson, ‘Letter to Dr. Jurgen Joedicke,’ December 6, 1961. Published in John M. Jacobus, Jr., Philip Johnson (New York: George Braziller, 1962), 120.

- Scott, p. 177. Scully quotes this passage from Scott in Vincent Scully. ‘Modern Architecture: Toward a Redefinition of Style,’ Perspecta 4 (1957), 9. The quotation appears again in Vincent Scully, Modern Architecture: The Architecture of Democracy/The Great Ages of World Architecture Series (New York: George Braziller, 1961), 45.

- Gerhard Kallmann told the author (May 22, 2008) that the perspective section of Boston City Hall was one from a set of renderings completed in the firm’s office after design work was completed to explain the structural system and interior spaces for a publication, though their haziness seems to obscure rather than reveal the building’s qualities, ‘The New Boston City Hall,’ Progressive Architecture, v. 44 (April 1963), 137.

- Rudolph and Fowler had frequent disagreements. Author’s interview with Rudolph office employee, William de Cossy, June 22, 2007.

- Norman Foster, ‘Norman Foster on Paul Rudolph,’ Architects on Architects, edited by Susan Gray (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 29. Foster said much the same in an interview with the author, January 21, 2002.

- Helmut Jacoby, New Techniques in Architectural Rendering (New York: Praeger, 1971), 64. Himself a leading renderer who knew Rudolph well, Jacoby describes Oles’s work and provides examples of his perspective sections, 26, 42–45. The book is a catalogue of works by leading renderers of the day, many of whom used the perspective section in a manner similar to Rudolph. For examples, see: Donald D. Hanson, 57; and Davis Bité, who also worked for Rudolph, 112–117.

- The perspective section of the Yale A&A first appeared in print soon after the December 1962 groundbreaking: ‘Yale’s New Art and Architecture Building,’ Architectural Record, vol. 131 (January 1962), 16–17. The original of the image depicted here is in the collection of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

- Paul Rudolph, ‘From Conception to Sketch to Rendering to Building,’ Paul Rudolph Drawings (Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita Tokyo Co., Ltd., 1972), 7.

- John Fowler, ‘Art and Architecture Building, Yale, USA,’ Architectural Design, vol. 34, (April 1964),160.

- Reyner Banham criticised Rudolph’s A&A Building and also saw it as wholly a manifestation of Rudolph’s drawing techniques. Reyner Banham, ‘Convenient Benches and Handy Hooks: Functional Considerations in the Criticism of the Art of Architecture,’ in The History, Theory and Criticism of Architecture, Papers from the 1964 AIA-ACSA Teacher Seminar, ed. by Marcus Whiffen (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1965), 91-106.

- Joseph Giovannini, ‘If There’s a Heaven, It Should Expect Changes,’ The New York Times, Thursday, August 14, 1997, C1, C10.

- Paul Rudolph, ‘From Conception to Sketch to Rendering to Building,’ Paul Rudolph Drawings (Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita Tokyo, Ltd, 1972), 11.

Timothy M. Rohan is associate professor and chair of the Department of the History of Art & Architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is the author of The Architecture of Paul Rudolph (2014) and edited, Reassessing Rudolph (2017). In 2008, he curated the exhibition Model City: Buildings and Projects for Yale and New Haven by Paul Rudolph in conjunction with the renovation of Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building. He is author of numerous articles in the Journal of Architectural Historians, the Art Bulletin, the Architectural Review, Art in America and more.