8 Smart’s Place: Making Sense

This text concludes a series of studies by Emily Priest that began at Shatwell Farm during her stay on site in September 2023.

How do you organise an architectural archive? Should it be ordered alphabetically? Should it be ordered by date? Should it be ordered by size? Should it be organised by type of object? How do you organise an architectural archive?

Maybe there is not one singular system that works and we should simply do what makes sense—or so I am told.

The main hurdle of using any archive, collection, or library is making sense of it. You can explore, happening across things, or through repeated visits intuitively re-find things, but an interaction with the archive takes on a different form through its order and systematisation. Rarely is an archive system easy to understand from the get-go and it is nearly always easier to ask someone to point you in the right direction. The challenge with the Drawing Matter archive is that it is full of very different objects, from small to large scale drawings, sketchbooks, paintings, models, games, tools, furniture, spectacles, and even clothes. It is impossible to have a singular storage solution; the collection must inhabit its room in a way that makes sense for itself and each object.

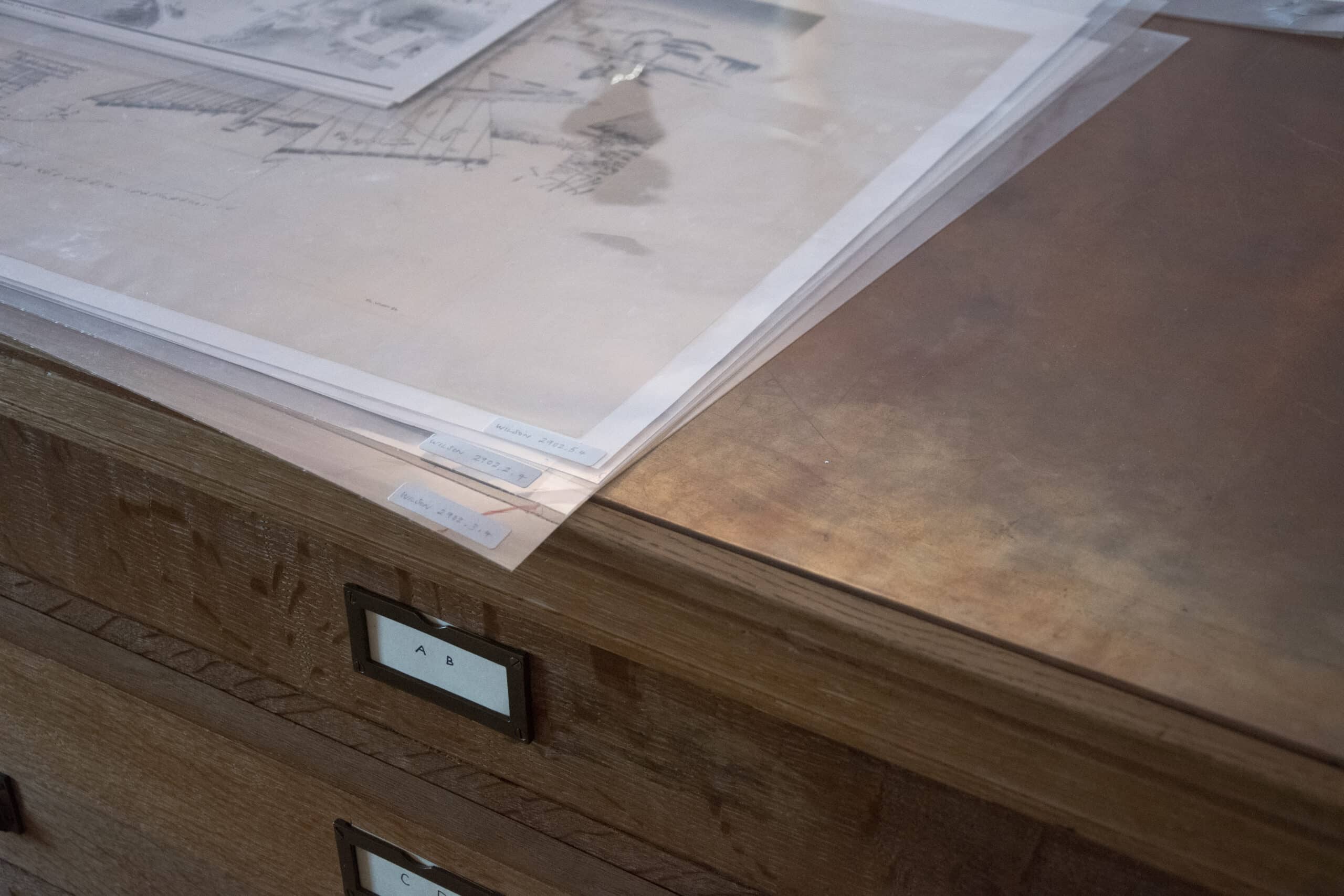

In its new location at Smart’s Place, there are three plan chests which sit in the middle of the room askew to each other; two are topped with metal, the other buckram and trimmed with leather. The metal is patinated around the edges with marks from fingertips. The plan chests are at such a scale, that their sides deserve to be called facades and their drawers, floor plates. They have been transplanted from Somerset.

The same recycled wool moving blankets (turned curtains) from Shatwell Farm are used to softly separate the entrance from the archive, the office from the archive, and the kitchen from the archive. The same cabinet of sketchbooks stands against a similar shadowy wall, and the same threaded wool pin boards now double as window shutters when in use. The same floral and smoky smell of Florentine potpourri masks the room.

A run of new timber shelves line one wall and hold a multitude of objects; models, boxes of drawings, ephemera (including a pair of Cedric Price’s glasses), and smaller framed works. The selection of large-scale framed works have found their place on the walls. Two models hang from the ceiling and could be mistaken for lamps. Floor lamps stand around, peeping over or reaching out across the table and chests, like skeletal limbs holding their last choreographed pose. The curious cabinet of Ruskin’s rocks is safely in the archive office as it was before. The desks in the office are drawing boards, previously owned by Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo, covered with pin holes and doodles (if you look carefully, there is a slight sketch of a nude woman). There are a pair of new portfolio racks, which look like caterpillars on wheels, folders sitting neatly between their spikes.

There are labels on the drawers and portfolios; everything is written by hand. But these labels sit amongst other marks made prior to Drawing Matter moving in; written in black marker on the window frames it says, ‘FFL mm’ (finish floor levels); alignment arrows and the word ‘steel’ are scribbled across the raw toothpaste pink plasterboard ceiling to indicate where the structure and services are above; and peculiar worn patches of timber floor suggesting where people or machinery have once stood. All these marks have been made by the people and objects working in the room. It is a palimpsest and Drawing Matter is its newest layer.

There is joy in the resistance to resetting the space, an approach which reveals itself in the collection by allowing objects and drawings to have a place that is relative to themselves. Its ordering makes sense, it is intuitive, the location of objects not governed by an overarching system. Drawings are in drawers, models are on shelves, sketchbooks are in the cabinet and portfolios are in the caterpillars, with some delightful exceptions in between. But there are almost always things out of place, on the table or in the ‘to be organised’ drawer. There are things to see before you have started to look. It is an archival practice that lives, forming uncanny connections, contradictions, conflicts, and anecdotes, all as a consequence of the space.

Thank you to Rosie, Matt, Martha, Jesper, Kendra, and Niall whose conversations influenced this and the previous essays in the series.

Emily Priest is an architect and writer from the UK West Midlands.

– Emily Priest