Shatwell Farm: Sheds and Silos

This text is the second in a series of studies of Shatwell Farm made by Emily Priest while staying on site in September last year.

Shatwell sits on dusty yellow Bridport sand encircled by limestone. Most of the farm’s ground is flat, except for its western edge, which creeps up to The Farmyard hotel. Rather than the picturesque, terraced vistas we might expect of Somerset—and perhaps the kind offered by the hotel next door—the farm’s topography is seen through glimpses. When on the farm, structures are not often seen nestled in their landscape, unless one stands on the north ridge and looks back towards the Smithson’s Obelisk. Otherwise, the landscape is seen through gaps between sheds, their large openings and working innards.

The sheds tilt and turn away from each other. They abide by the land and subtle opportunities of level ground. The farm roads bend, widen and narrow to suit; probably having come as a result of the buildings, or even by way of routes most trodden. Apart from the 2015 Stephen Taylor cowshed, none of the buildings are used for their original purpose. Niall explained this is because ‘we try to make everything here relate somehow to the archive…apart from the cows, because the cows came before us.’

The original 19th-century sheds previously housed cows and horses when Shatwell operated as a dairy farm. In 2014, one of them underwent refurbishment for the office and archive. Hugh Strange Architects incorporated a cross-laminated spruce structure behind the original masonry envelope. The brickwork has been left as is, or as was. Former windows are now mantelpieces for the hardier members of the collection and are backgrounded by silvered spruce. The barn’s gable end and new zinc roof are offset from each other to allow a higher ceiling inside. The south wing of the building remains undeveloped; its historic timber roof is wobbly, but intact, and supported by Acroprops. The central shed, which can be seen in historic drawings, is no longer there. A skip and recycling bins are now in its place.

In the 1960s, the farm expanded with a family of prefabricated structures: the Atcost shed, the Allen & Co. barn and two Simplex silos. Atcost is a company that was established in the 1950s to design and construct industrial buildings. The Atcost shed at Shatwell is of modular construction and comprises two barns that share a central structure. The shed has chunky precast concrete columns and rafters which teeth into articulated purlins whose ridges allow the corrugated concrete roofing to hook into place. Fixtures are dry and reversible, as if the shed could be dismantled and relocated. In 2021, Clancy Moore Architects built within and around the Atcost shed to facilitate spaces for storage, education and performance. Currently, a picture framer, Mount, occupy the ground floor unit and Comins Tea run a tea house above.

In areas seemingly outside of Clancy Moore’s intervention, the corrugated metal is patinated, dull and sometimes distorted; damaged in parts and warped with wear. In instances where the cladding has fallen off all together, nothing has been done to replace it; openings have been made and odd courses of blockwork and brick are exposed. These masonry courses have generous and messy helpings of mortar, which, when wet, must have squeezed through the masonry and pushed against the corrugated panelling before it fell off. There are layers of stories signifying moments in time, approaches to repair and multiple types of hand.

The Allen & Co. barn sits north of the Atcost shed and follows a similar construction technique. It is also concrete, but far more elegantly designed. Its purlins are lighter and taper out to slender dimensions. The roof of the barn is divided by a central run of columns and has reversed beams on either side. One portion is pitched, and the other slopes down to meet an additional timber structure and masonry wall. Allen & Co. are no longer in operation but was a local company from Castle Cary. There are only two of these barns left in Somerset: the one at Shatwell, and another at Hauser & Wirth in Bruton. This barn is currently leased by the Timber Frame Company, who also have their office on the farm.

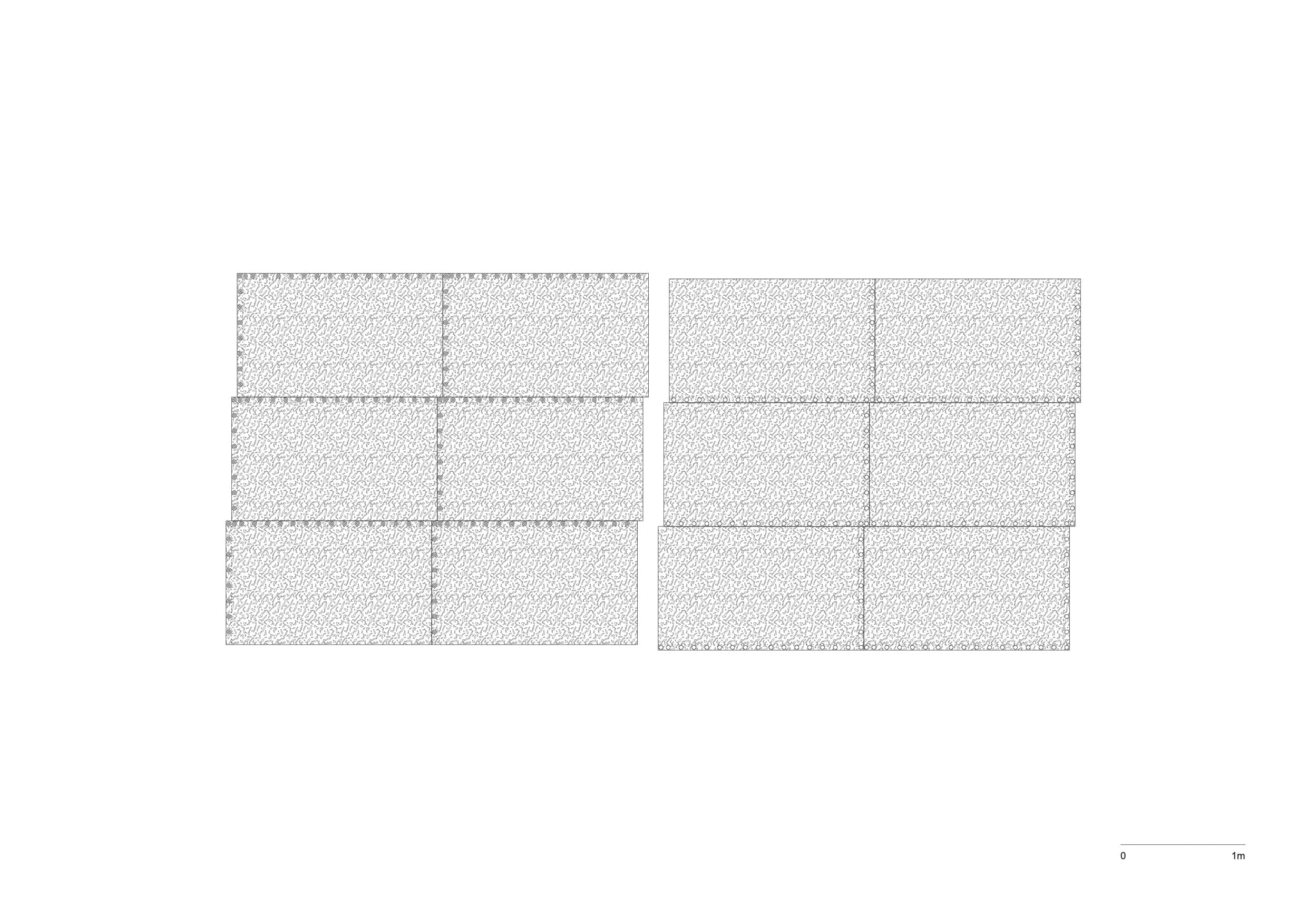

Of the two steel Simplex grain stores, one is currently used for music performances for its good acoustics, and the other, a tool shed. At one point, the silos were going to be converted into a library, but this project was never realised. Little has been done to convert them into their new uses, except for cutting ground level entrances out of the galvanised steel panels. The panels overlap on two sides where they are bolted together; there are 11 panels in total for each section in plan and 7 panels in height. The overlapping seams mean that only one layer of steel is required, fabricating an engineered stepped pattern in elevation.

The silo used for performances was left empty. It had a music stand in the middle and some rivets were painted bright blue and pink—the rivets are part of an installation by the artist Tarka Kings called ‘Grace Notes’. The tool shed has a scaffold frame with a mezzanine fitted inside it. Amongst other odds and ends, it stored spray paints, ladders, event signage, bags for life and barrier fencing. The tools, equipment, and event leftovers necessary for a modern operational farm. The library has since found itself in two shipping containers designed by Cedric Price. The containers sit on the western ridge of the farm, the only location that could be reached by crane.

When walking up the west track towards the libraries, the sheds and silos slide ‘like palimpsests over each other.’[1] The pitched roofs, now more visibly layered in height, speak to each other and new views offer themselves up. The placement of buildings is more consequential than designed and they are stitched together by overgrown grasses, hogweed, and nettles. Niall said that the Shatwell Farm buildings weren’t built to be looked at. I am not sure how far I agree, but perhaps it was less an overarching statement, and more a gradual day-to-day approach that, over time, has culminated in a collection of buildings brought together by use, need, changing need and repair. There is a pleasure in leaving things alone and fixing them when needed. The sheds and silos share a conscious dialogue that mediates careful mending and getting jobs done. Things are made useful and a lot of things are left alone.

Emily Priest is an architect and writer from the UK West Midlands.

Notes

– Emily Priest