Architectonic Landscapes

This text is the fifth in a series by artist Deanna Petherbridge in which she comments on a number of her recent pen and ink drawings. The drawings use imagined architectural imagery as a metaphorical means to deal with complex subject matter about social and political issues. Read the introduction to the series, here.

It seems pertinent to begin with one of the many up-beat online dictionary definitions of ‘architectonic’, that of Thesaurus reading as ‘having qualities such as design and structure that are characteristic of architecture: a work of art forming an architectonic whole’. It’s wonderfully reassuring that authoritative linguistic communities equate architecture with resolution and wholeness. Webster’s dictionary even goes so far as to define the term as ‘resembling architecture in disciplined organisation and design’.

These definitions are flagged up to reinforce my claim that my landscape drawings, framed by their titles and subject-matter, have gained some value, or at the least, gravitas from their relationship to architectonic form.

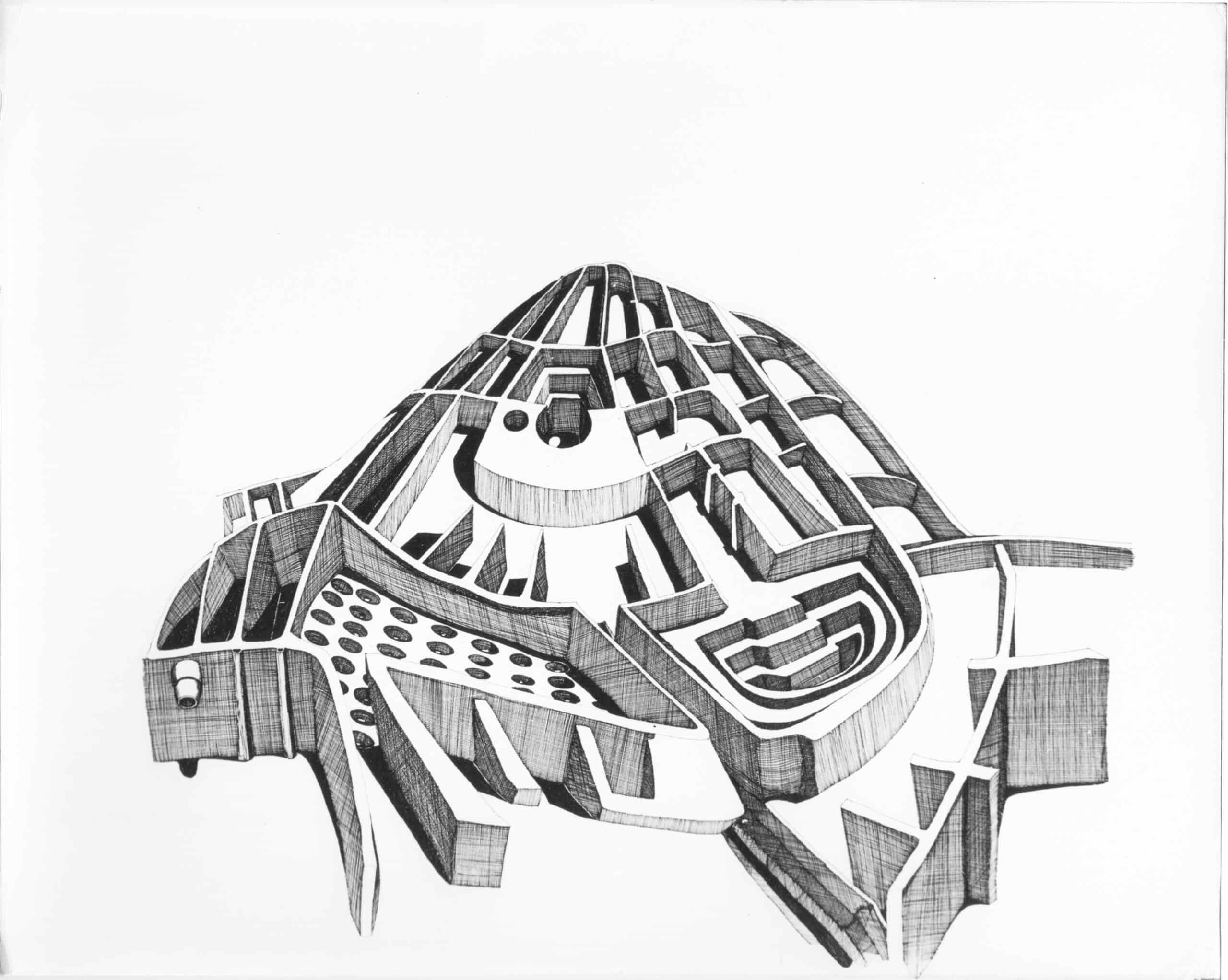

When I radically changed my practice in the 1960s from painting and soft sculptures into pen and ink drawings on paper inspired by the vernacular architecture of the Maghreb, Mediterranean and Middle East, the impetus was to embrace underlying formal values that were radically under fire at the time from Pop Art (except perhaps for Richard Hamilton) and abstract expressionism, which were sparring under the customary modernist rubric that ‘painting is dead’. An early (and now lost) drawing of mine, made when I first went to live on the Greek island of Sikinos in 1967, translated the terracing, the white roofs, the circular threshing floors, the stone windmills and the buttressed walls of chapels into a totalising architectonics. The terraced Cycladic island, like its neighbours, was almost entirely man-made; its rock-built unity bleached into intense contrasts of light and shade adding beauty to the physical hardships of an isolated community eking out a subsistence from small stony fields. The clarity of shadows in this series of drawings followed from close looking, analysis and homage to the poet Giorgos Seferis (1900–1971), aligning the agony of post-civil strife and war-torn Greece with the austerity of its sun-drenched islands.

Now, fifty years later, I am proposing that the architectonics of my recent ‘political’ landscapes, which do not relate to real topographies but construct imaginary environments as metaphors of the domain of politics, gain a certain resonance through underlying abstraction, geometry and measured proportions.

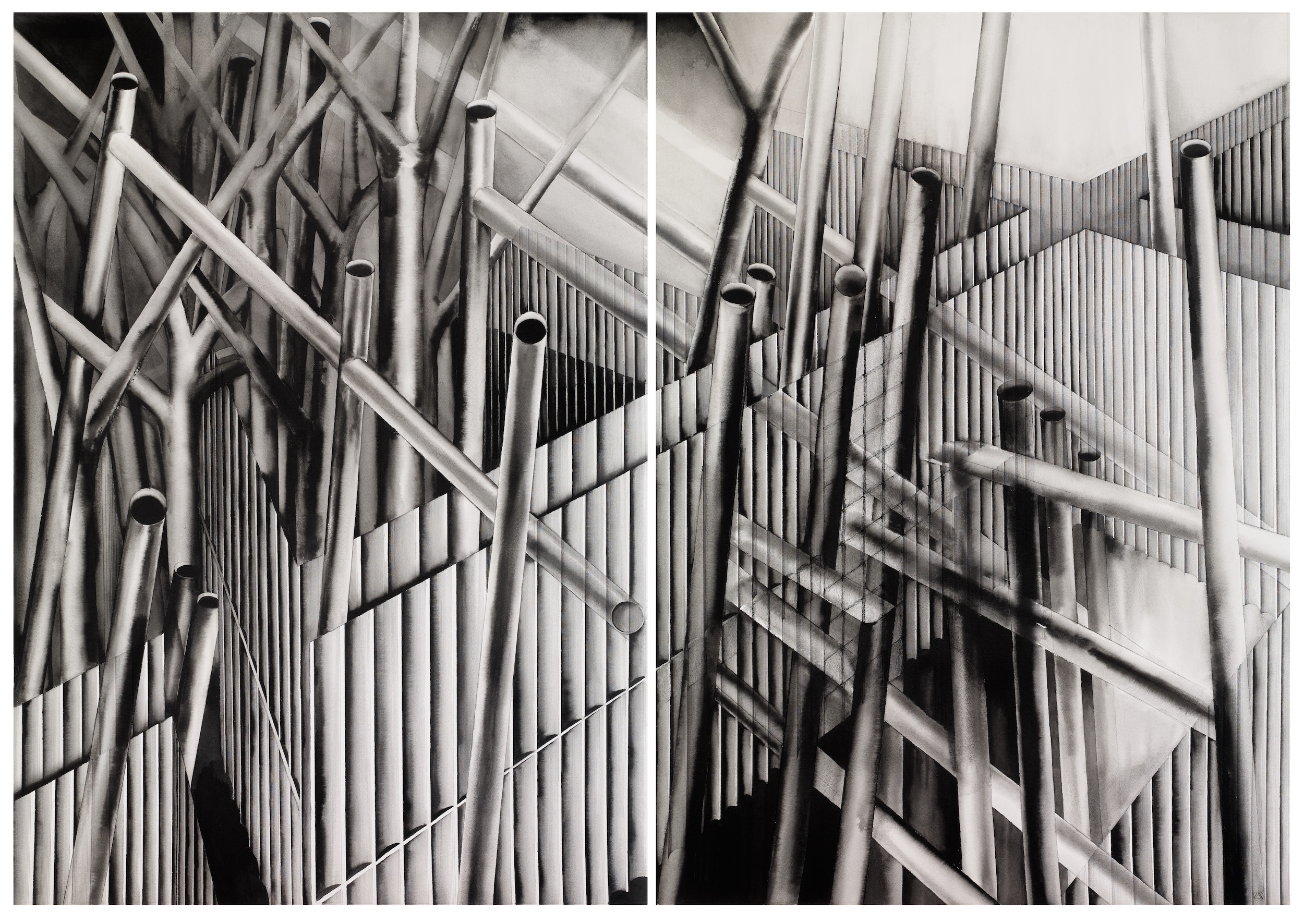

The drawing Transparency and Lies is an exercise in contrasts: between mechanistic forms – that is, simple tubular shapes and biomorphic forms suggesting stripped wintry trees; between strict enclosure walls and rampant proliferation of motifs in illogical spaces; between solidity and transparency, metal and glass, backwards and forwards. The investigation of transparency in the right-hand panel plays with the overlay of the patterning of the back vertical plane projected on to frontal transparent tubes as a form of double entendre.

These contrasts are described in words as binaries, whereas nowadays critical thinking aims to challenge the philosophical construction of sharp dichotomies and opposed dualisms. However, the subject matter that I was exploring, the proliferation of political untruths and obfuscation promoted by populist leaders, specifically Trump and Boris Johnson, seldom contested although often refuted, seemed to demand a simple visual challenge. Especially in the light of thoughts that truth is indivisible. Possibly too, visual metaphors need to be formally simple at one level because playing with allusive material (such as indications of transparency or opaqueness) rather than direct representation of objects in the world about us constitutes an extended overlay of provocation and complication even before the subject matter can be decoded … and hopefully responded to.

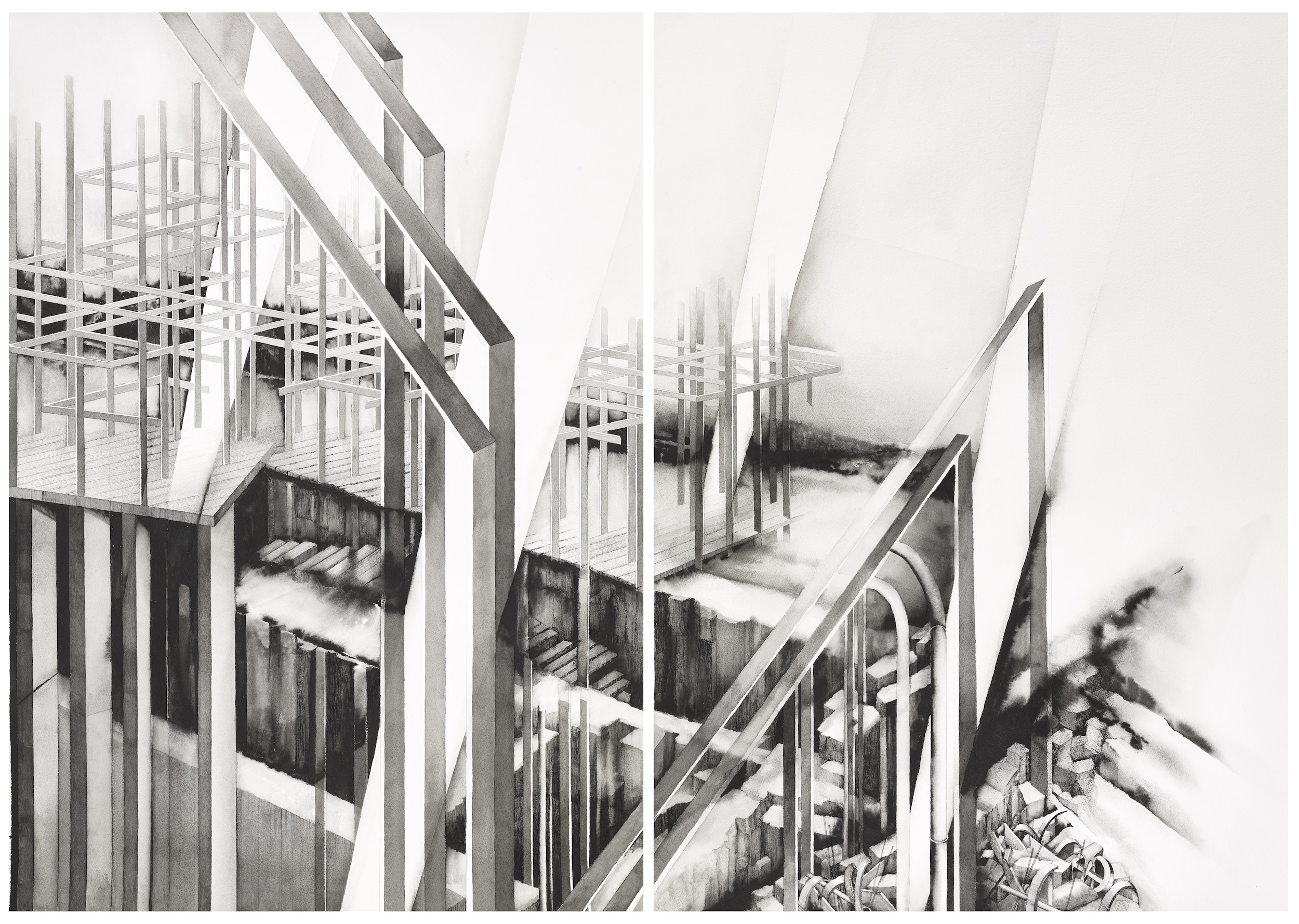

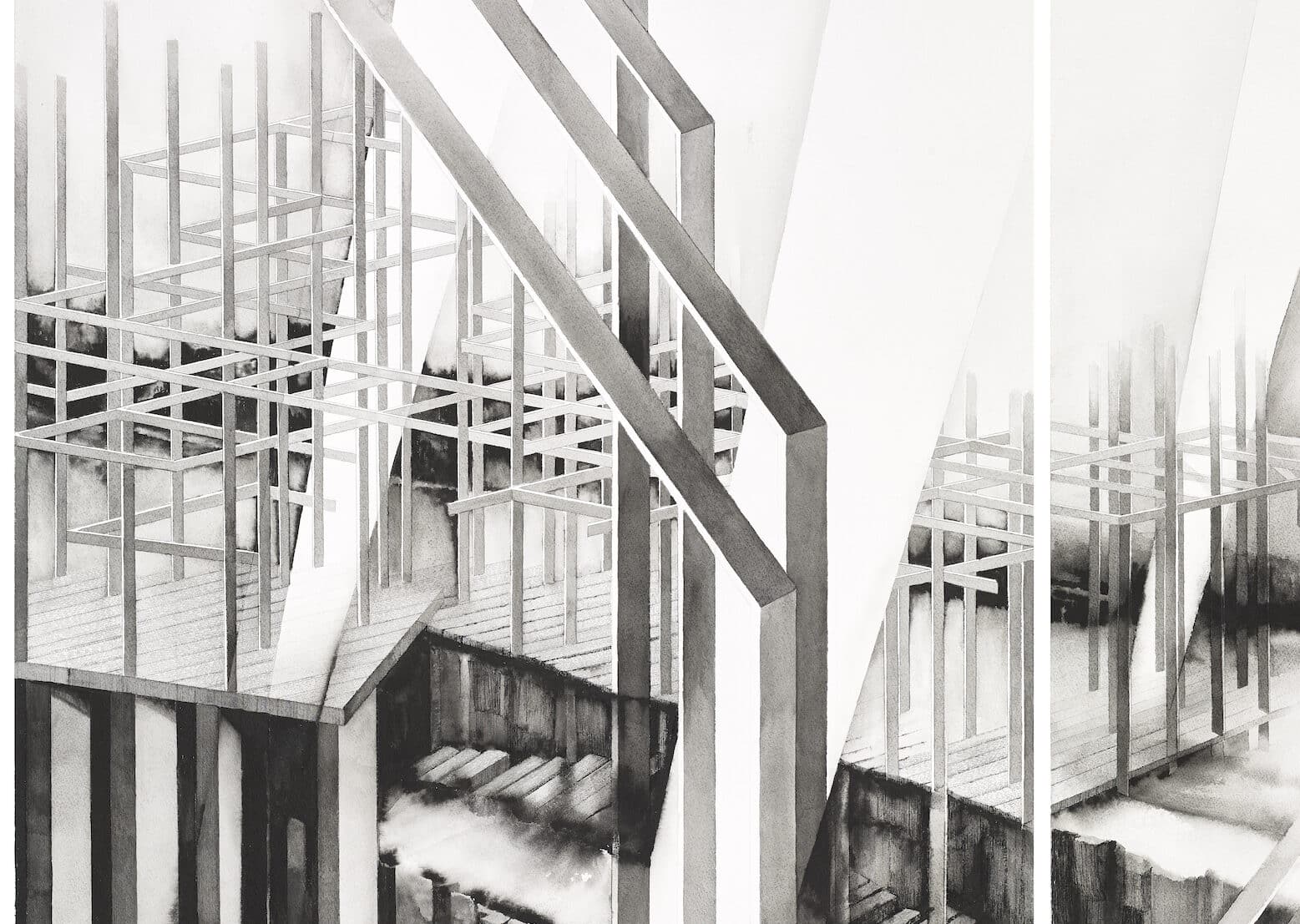

The recent diptych, False Promises of New Beginnings, was a response to Boris Johnson’s post-Covid slogan of UK ‘freedom day’, trumpeted in the face of the continuing threat of the pandemic and designed to draw attention away from shortages, rising prices and economic upheaval as a result of Brexit. The shafts of light like channels of hot air pronouncements rising from the plinths of these structures contrast with the barren ravines, death pits and chaotic rocks and detritus of the underlying landscape. I envisaged the traditional wooden platforms and interlocking timbers of future structures as being rooted in a mythical past of fixed and benign imperialist values: Rees-Moggville, perhaps. They are only lightly penned in the drawing, in an attempt to show-up their fragility and transience.

Thinking about the length of time that I have been deliberately working with architectonic values makes me reflect on the lasting effects of art training on the pragmatics of making. I used to regularly notice the persistent aura of ‘taste’, style and aesthetic preferences formulated during studentship that seemed to cling to architects throughout a lifetime. It manifested itself in issues of presentation, furniture design, or even the types of figures or art objects that populated their schemes, and of course their manner of drawing in private sketchbooks. This internalised aesthetic of a particular dateable epoch was, interestingly, not directly reflected in the variety of their design projects which closely followed the pragmatic exigencies of commissions, the demands of clients and major cultural and technical shifts.

I am now thinking that aesthetic persistence might be a condition of all those professions that have traditionally offered practical training alongside the theoretical and historical in long courses of study. I don’t have the information to speculate how or whether it also holds true in the domains of engineering or town planning, for example, but artists I know who have radically changed their practice over a professional lifetime, but maintained the base discipline and operative dynamics of studio production, have similarly internalised ways of working that were inculcated during studentship, however pushed to the limits by new aspirations and fresh opportunities in their subsequent careers.

This is not just a naive rediscovery of the importance of professional training and early learning (or perhaps it is!) but rather an assumption that the significant aesthetics that shape outputs over a career used to be those implicated within practice rather than adherence to theory, philosophy or history. And borrowing a term from Eyal Weizman’s recent book Investigative Aesthetics: Conflict and Commons in the Politics of Truth, which I will be discussing below, I am naming these as the operative aesthetics that I believe are embedded in making and invention. [1]

The impossibly wide and complex philosophical domain of aesthetics has always been applied to the thinkers, observers and consumers of cultural issues with the bold expectation – from Kant to Adorno to any of our contemporary fashionable gurus – that somehow the makers of art are on the same wavelength as their audience and critics. Or, if not, they need to be written out of the script. Of course, aesthetic judgements could never be as ignorantly complacent as this massive generalisation implies, but the current conviction in the world of culture that the demands and problematics of new technologies and fashionable theories are of over-riding relevance to artistic practice follows this pattern. From the enthusiastic and uncritical embracing of 3D printed photographs in the construction of the banal public monuments of our newly reconstituted social heroes, to the endorsement of prizes for teams rather than individual artists, the pressures to conform on art schools, galleries and individual practice are more coercive than they have ever been. Such assumptions require challenging … if only by the over forties and fifties who have a view of history. The aesthetics of making and materiality that guided visual practice alongside a knowledge of history in the past have been replaced by shifting, sexy theories clustered around the primacy of identity politics within our polarised but globally interconnected world today. Whether these can succour a lifetime of dynamic creativity and are a good or bad thing, I really don’t know.

These thoughts have been energised by examining the work of Forensic Architecture, who deal, in very different ways, with the political subject matter that I have been cautiously unpicking in this series of articles. Forensic architecture exhibited this year at the Venice Architecture Biennale and their presentation Cloud Studies at the Whitworth Art Gallery, as part of the 2021 Manchester International Festival, included the first phase of a new investigation on environmental racism on the banks of the Mississippi in Louisiana. Eyal Weizman, who runs the MA course of this title at Goldsmiths, London, has published considerably on the output of the research agency dedicated to investigating ‘human rights violations including violence committed by states, police forces, militaries, and corporations.’

Our investigations employ cutting-edge techniques in spatial and architectural analysis, opensource investigation, digital modelling, and immersive technologies, as well as documentary research, situated interviews, and academic collaboration. Findings from our investigations have been presented in national and international courtrooms, parliamentary inquiries, and exhibitions at some of the world’s leading cultural institutions and in international media, as well as in citizen’s tribunals and community assemblies. [2]

The recent collaborative book Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth co-written by Weizman with Matthew Fuller has boldly co-opted a hugely expanded view of aesthetics that functions ‘beyond perception’ into a new, complex and wide-ranging manifesto, while acknowledging that ‘the use of ‘aesthetics’ in this book is distinct from certain other historical uses of the word’. [3] According to their argument, aesthetics embraces all forms of computational ‘sensing and sense-making in which all entities in the world play some part’. [4] This is exercised collectively by a huge range of ‘open source’ relational practices dependent on partial but highly focussed investigative skills in domains ranging from pattern analysis to photogrammetry to fluid dynamics, virtual reality and forensic oceanography. The insights of multiple investigative processes and collaborators are brought together in what the authors term a ‘poly-perspectival assemblage’. [5] They embrace both art and science, exercising ‘new formulations of objectivity’.

investigative aesthetics expands the sites of truth telling – from the courtroom, the university and the newspaper to the gallery, street corner and Internet forum. Each such site requires multiples kind of transversality to reform relation between groups, practices and sensory objects and surfaces and indeed necessitates conjunctures between different knowledge cultures … [6]

This all-embracive analysis is heady stuff and well argued in the main, if rather confusing when expanded to include those inimical forces under investigation. These evidently participate in exactly the same broad system of sense and sense-making aesthetics and reflexivity: there are no naughty binary simplicities of ‘them’ and ‘us’ in this dense text. The ambivalence of this position is predicated in the chapter on Hyper-aesthetics, which constitute ‘an elaboration of [the] general condition of aesthetics – its interlinkedness – to a point where it mutates and becomes reflexive’. [7] In the chapter on ‘Aesthetic Power’ the authors admit that ‘targeting and prediction’ is one of the main manifestations of state and corporate power today, which like any other kind of aesthetic power ‘seeks to affect, stir and influence the very things predicted ‘… ‘the two modes of aesthetic power combine and entangle.’ [8]

The chapter on Secrets, establishes that prediction and detection are co-dependent and concludes that ‘both the secret and its exposure need to be thought in aesthetic terms’ albeit as a paranoid form of the hyper-aesthetic. In the final chapter, Investigative Commons, after the authors have proposed that ‘sense-making implies a certain kind of invention in creating alliances and relations between sensing entities’, [9] they package across-the-board aesthetics, surprisingly, as both reality and common sense, generated ‘ecologically’ but escaping earlier notions of universalism:

the commons is woven together by a multiplicity of difference – of participants, perspectives, situated experiences, position and forms of knowledge produced and worked at by practical and experimental intersections. It is a shared rather than a unified or unifying condition. [10]

The Forensic Architecture agency has undoubtedly undertaken extremely important investigations, mounted significant and enlightening exhibitions, given invaluable evidence at tribunals and Weizman has written with insight about human rights, migration and displacement, domicide, battle damage. [11] But I was relieved to turn from the excessive theories of Investigative Aesthetics to thinking again about the values of unitary art practices where the artistic intention is to manipulate formal and conceptual elements into a visual synthesis open to a meditative or critical audience. Perhaps the impetus behind this form of practice, honed through the internalised operative aesthetics of making is the reaching towards a poetics of visual form: that ancient notion encapsulated in Horace’s dictum of ut pictura poesis. In this regard, I was moved recently by reading an interview with the Russian-Ukrainian/American poet and author of Deaf Republic, Ilya Kaminsky

Every great poet is a very private person who happens to write beautifully enough, powerfully enough, spell-bindingly enough that they can speak privately to many people at the same time… Not play for the sake of mere play. And not a public pronouncement either, but a very private speech that the form teaches you how to partake in. [12]

Speaking privately to many is a significant, if whispered, rebuff to populism. Lucky are the visual artists who achieve it and the audiences that participate in it.

Notes

- Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (London and New York: Verso, 2021).

- https://www.gold.ac.uk/pg/ma-research-architecture/

- Investigative Aesthetics, pp. 43 & 51.

- ibid., p.196.

- ibid., p.6.

- ibid., p.118.

- ibid., p.57.

- ibid., pp.93 & 96.

- ibid., p.196.

- ibid., p.198.

- See Eyal Weizman, The Least of All Possible Evils: A Short History of Humanitarian Violence (London and New York: Verso, 2011, 2017).

- https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-ilya-kaminsky/. (Interviewer Joe Dunthorpe), August 2020.