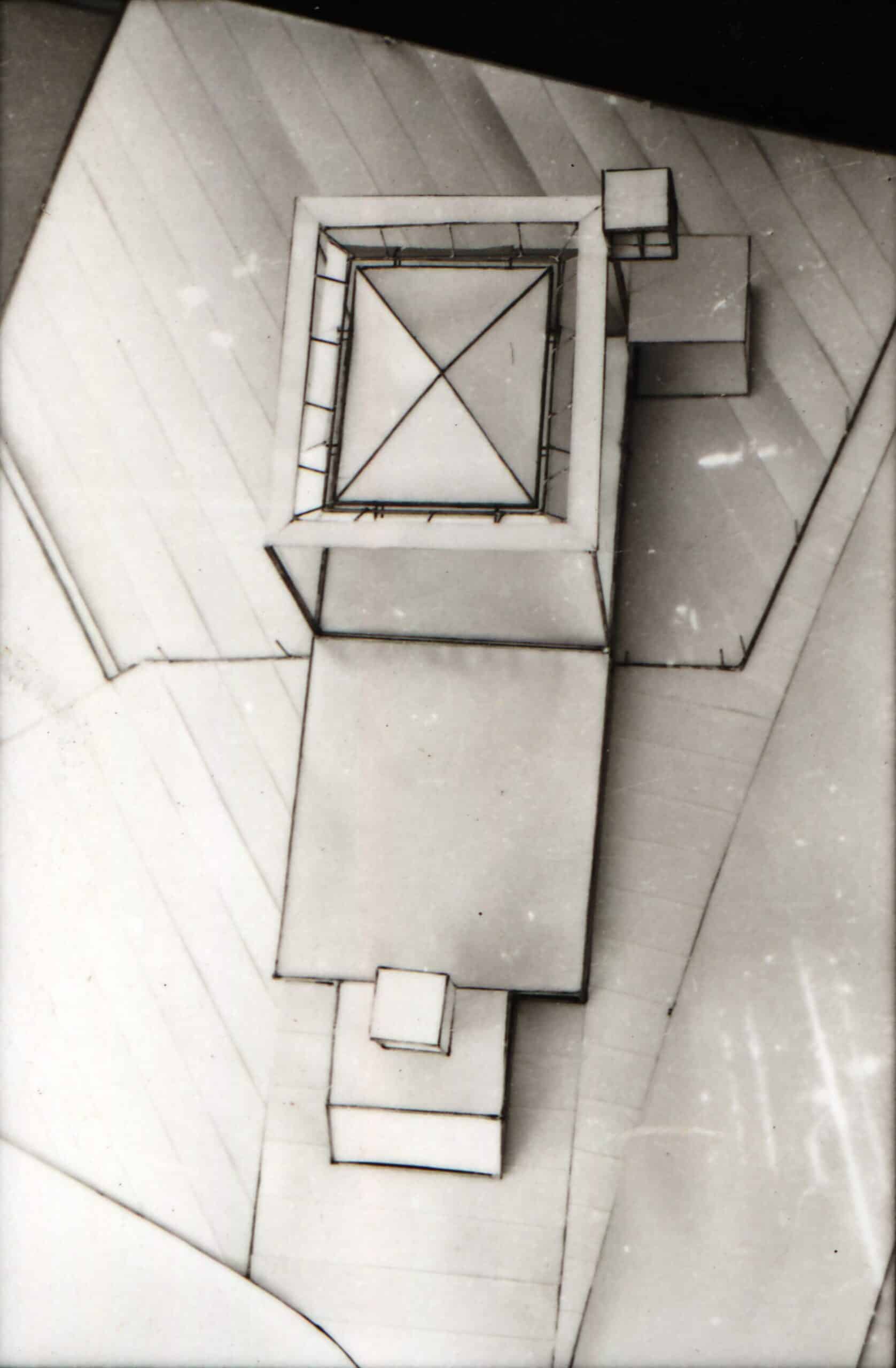

Capilla Pajaritos

The following text was written by Alberto Cruz as an account of the project for a small chapel outside of Santiago (1952–3; first published in Spanish in 1954). It describes an unfolding process of design, framed around the guiding principles of observation, act, and, form—the key tenets of Cruz’s architectural method. It is the third text that Drawing Matter has published on Cruz and his work. The first was a review of the exhibition Observation, Act, Form at the Architectural Association, and the second, another original text by Cruz on the Palace of Dawn and Dusk.

A

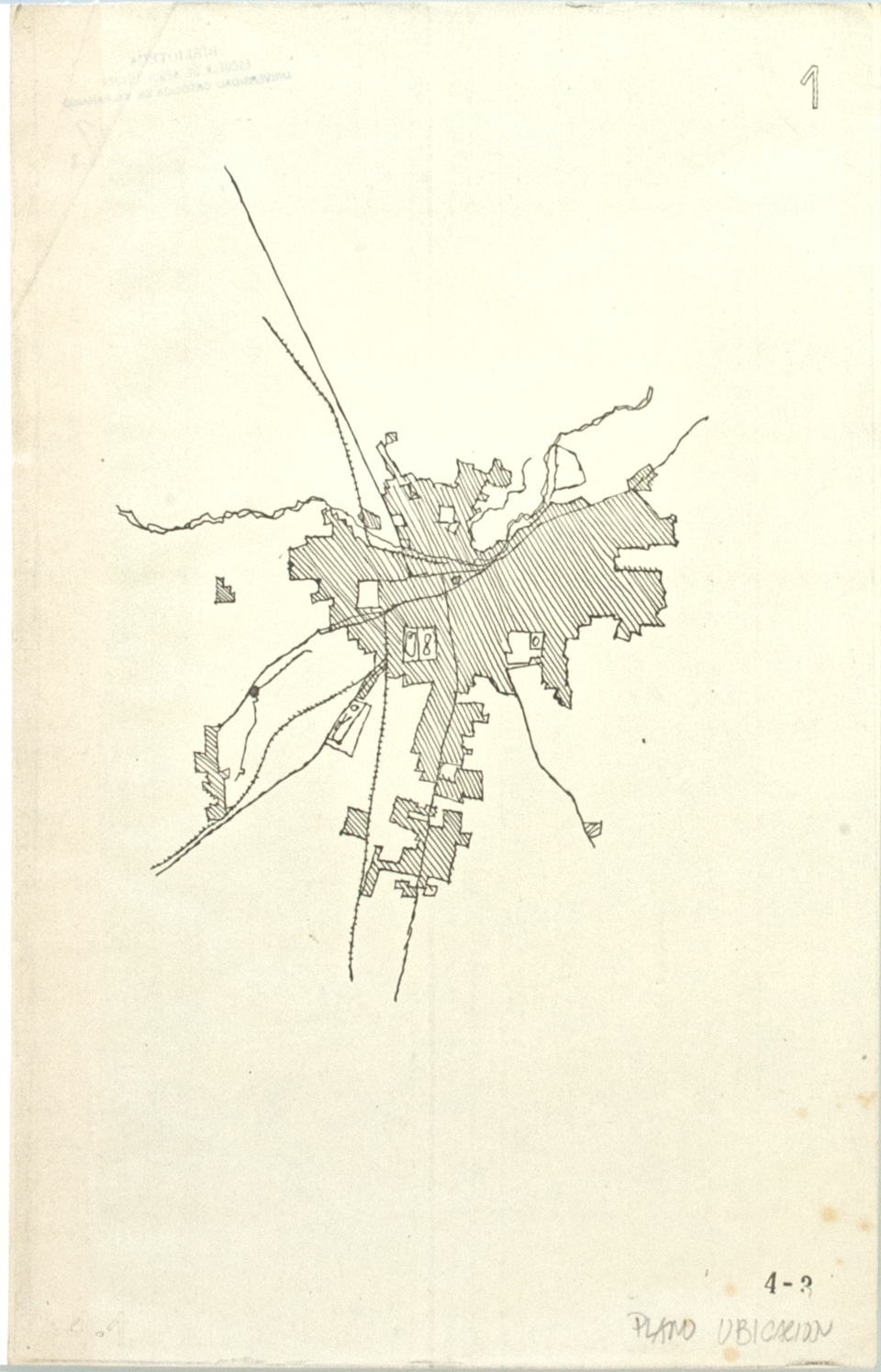

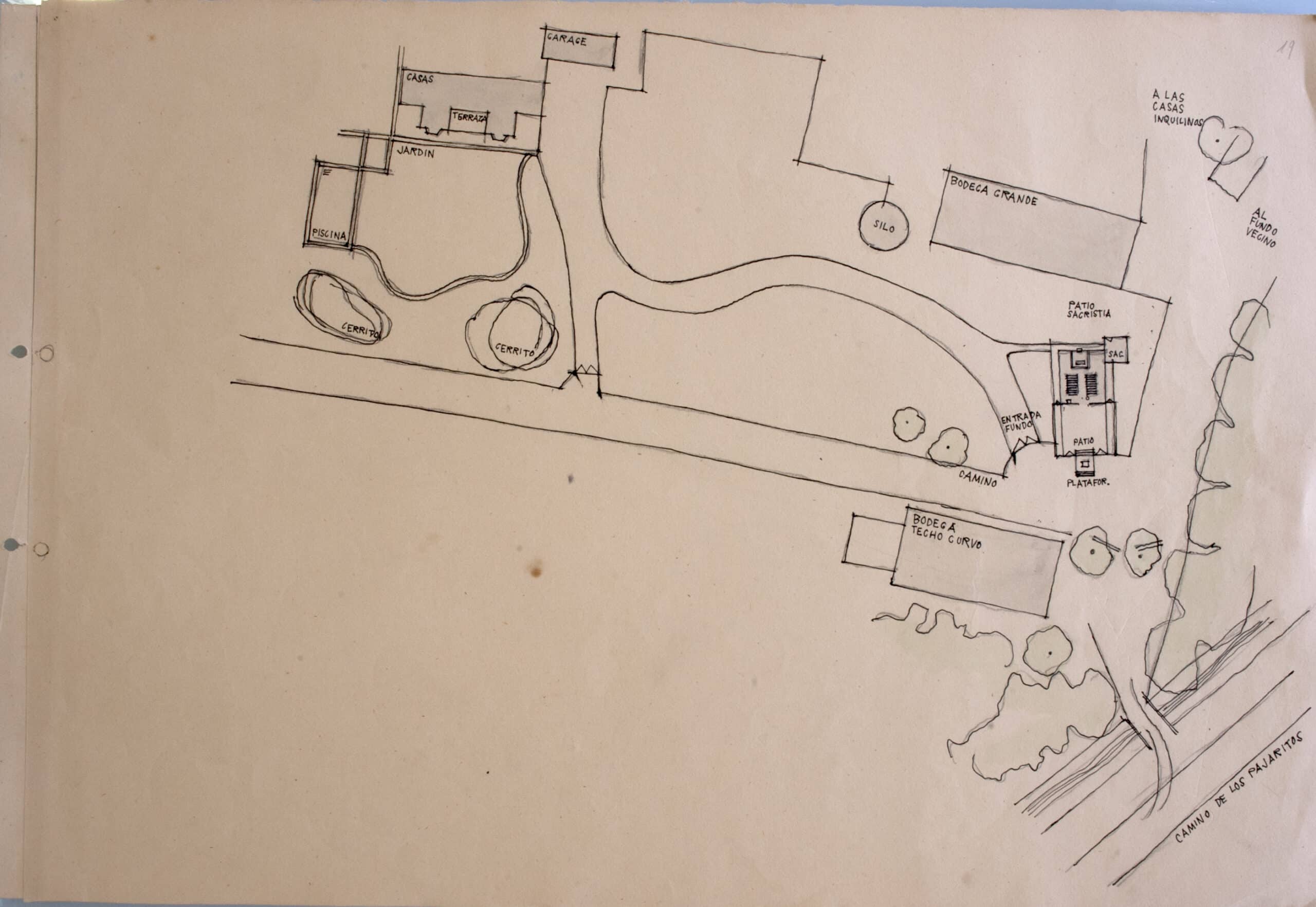

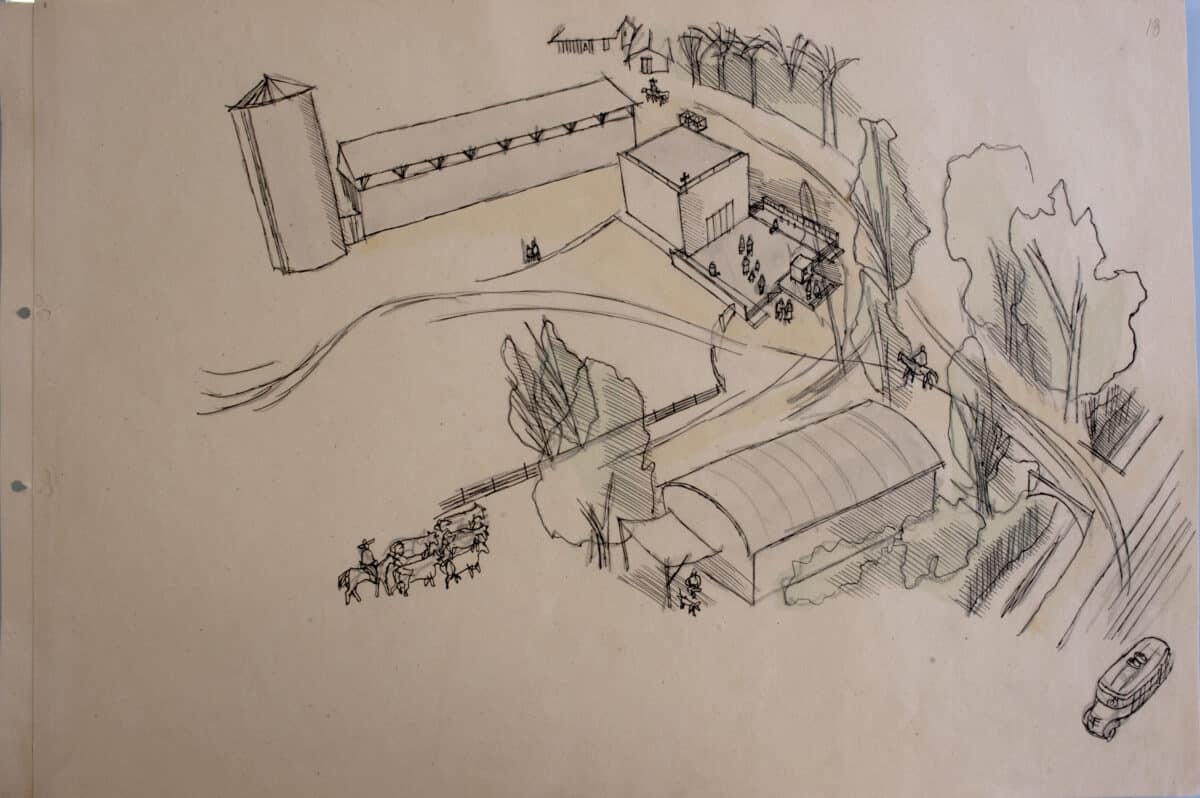

A memorial chapel at the entrance to an agricultural estate in the outskirts of Santiago, that seeks to adapt to the uses and customs of the estate’s owners.

B: The act

1. The work is conceived in the presence of poetry. References: an act in the presence of spectators, a professor in the presence of an audience of students.

2. The work unfolds in two magnitudes: when one is inside it, one is inside the chapel and one is also on the country estate. An architectural work combines two modes of the here: it is what it is in a room and in a house, in a neighbourhood, in a city and in a country.

References: The objects—bottles, guitars, etc.—from the first period of Cubism are not in a same ‘here’ but in another, more broader ‘here.’ See note [below].

3. The act of inhabiting in two modes of ‘here’ is also true with passions. Observations: the face.

The face: the gaze, we seek the gaze of others, the other seeks us out. The nostrils, we scarcely ever even notice them.

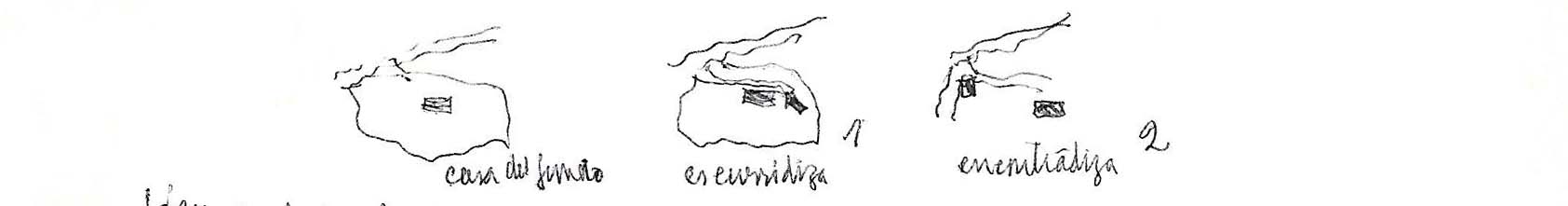

The possibility created by Cubism can be pushed just as one person’s eyes search for the encounter with another; or like nostrils, it can be elusive or slippery.

You have to choose between 1 and 2. These choices, in the presence of poetry, mean standing before freedom. First and foremost, the freedom to choose.

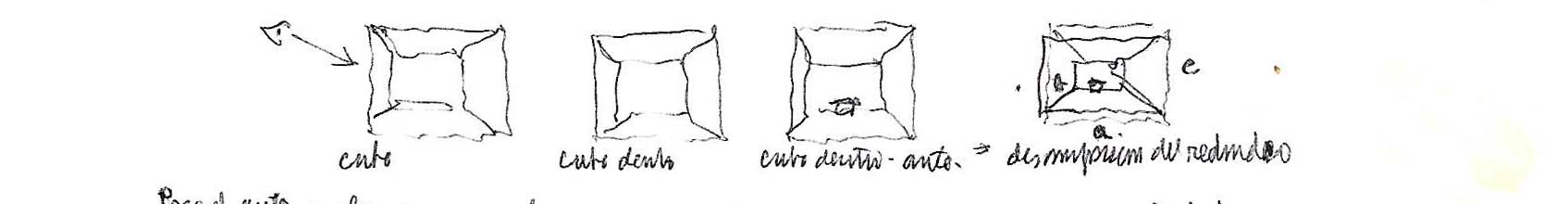

2 is chosen and it establishes a relationship through continuity with the more expansive ‘here’: the ‘here’ of the city, of Santiago. A city, in itself, is a set of works that insist on being findable. It is for this reason that the city tends to be frontal.

The very location of a work builds frontality in the urban sense. In which the location is always, ultimately, the end point that provides a conclusion by extending out from the depth [note: depth of Santiago].

4. The chapel is—by nature—a place of prayer. Prayer: in the presence of God. Chapel: in the presence of the altar. Observation: in the city on cold days the most dispossessed stand in the presence of rays of sunlight that warm them up. They live on the peripheries of cities next to roads or natural landscapes. As such they assimilate the presence of the sun and distance. They consummate a ritual of both.

Prayer involves a ritual of sun and one of distance. It is done with a previously existing ritual. That allows both rituals to take place. But that previous ritual is not observable: it occurs through them. And so a chapel must:

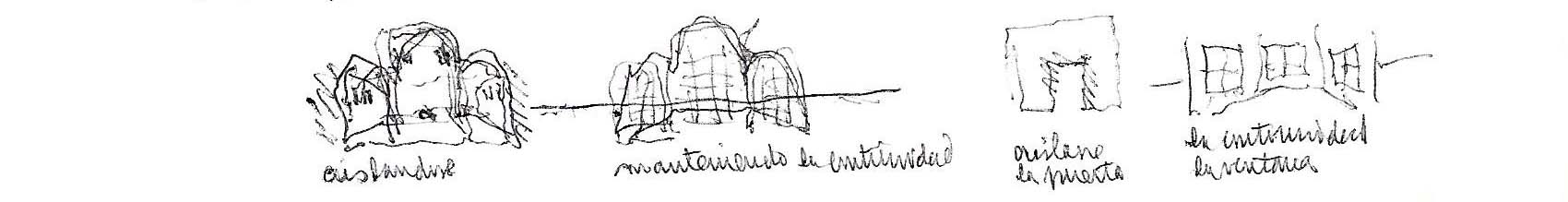

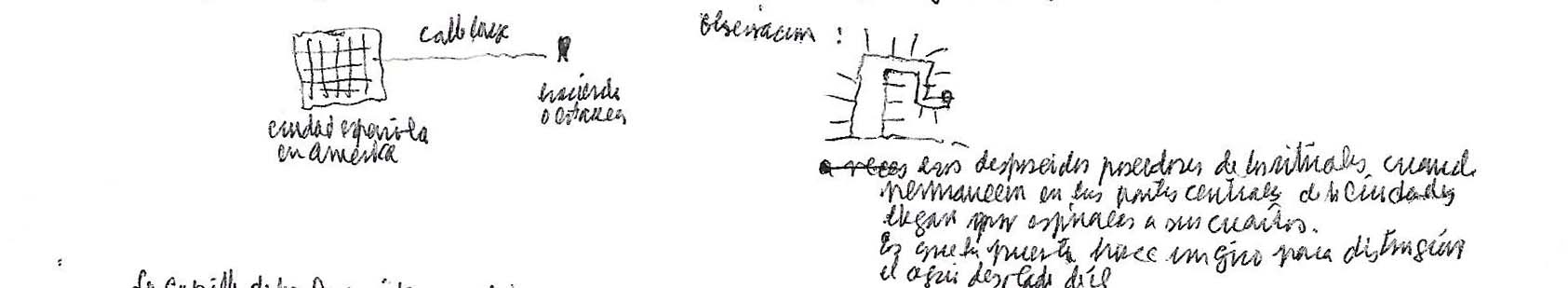

The door and the window are the two great inventions of the immediate here. For this reason we must choose between them.

5. Windows and doors are also, with the passion that comes from inhabiting: observations

Doors and windows are opened and closed, or else they are left half-open and semi-closed. Always closed or open: annoyance. Open and close: a matter of modesty. But modesty and annoyance speak of the un-regulatable, the elusive. Only for poetry. Yet everyone can perceive that annoyance and modesty speak of man’s eternal re-beginning. Or his act of inhabiting. And so there is praise, the most characteristic thing of the act of inhabiting: the most restorative.

And one must:

From another light; the semi-darkness opposed to the chiaroscuro and the non-attenuated. But returning to the ‘here’ of a house and the city. What is said about semi-darkness is valid for a room but certainly not for a city. It is valid for the mass of semi-darkness of a room. It is characteristic of the ‘here-here’.

Semi-darkness is chosen as the most restorative act of inhabiting the chapel.

These are the passes that are given before poetry to constitute the act of the work.

C: The form

a. The architectural form is, first and foremost, a configuration in the natural visible space.

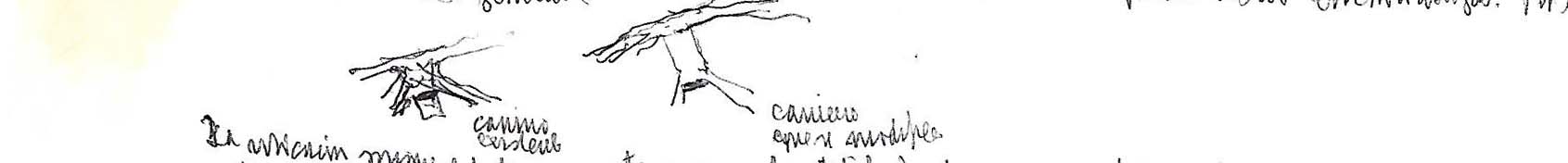

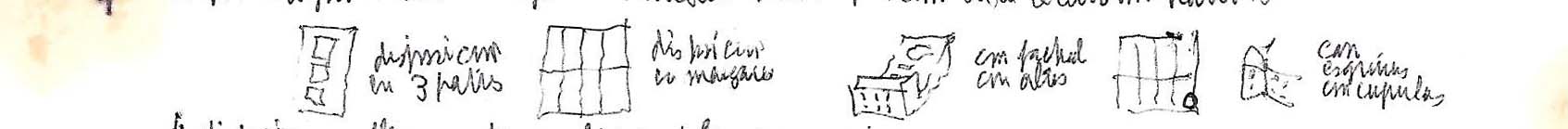

) / con fachadas con altos (facades with height) / con esquinas con cúpulas (with corners with domes)

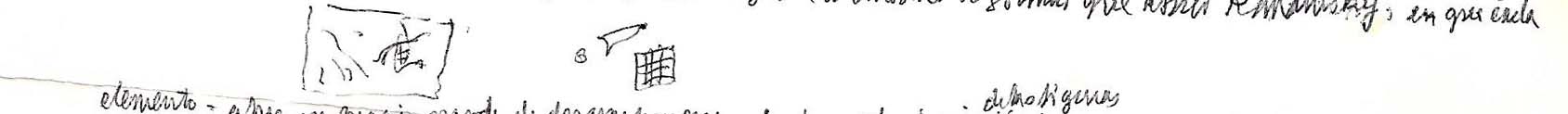

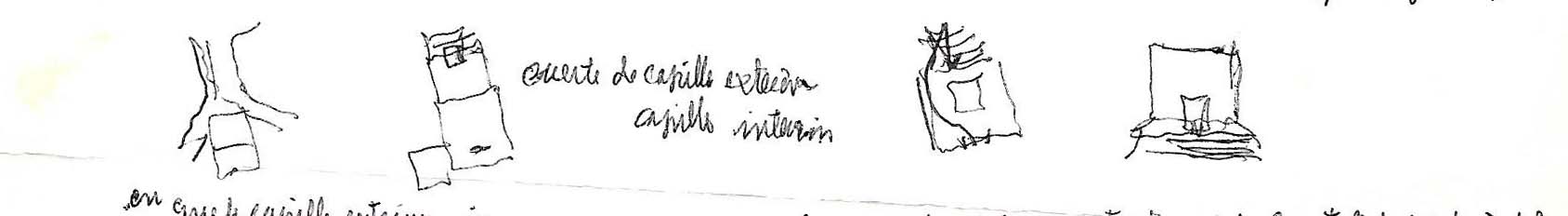

The configuration is carried out through figures that look like this:

The architectural act is conceived through rounded figures.

But a work is not just the configuration of rounded figures, which does not deliver that restored act of inhabiting. For this reason it is necessary to reconsider the act of the rituals of sun and distance that occur in the passions of modesty and annoyance.

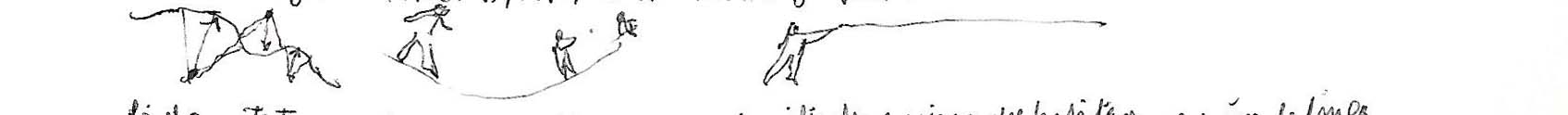

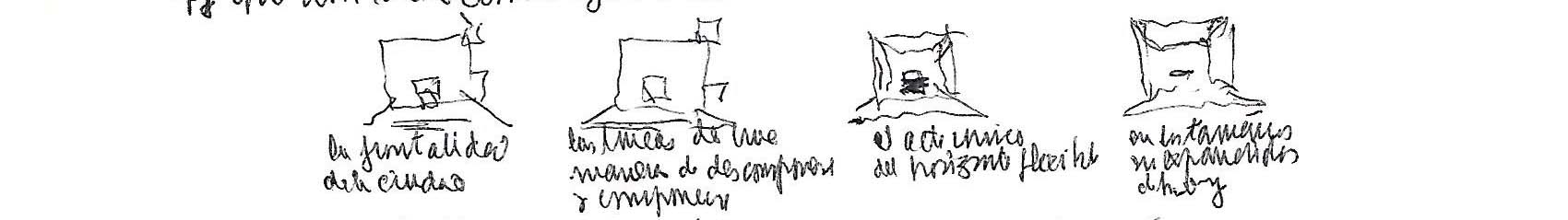

Reconsider means: for an instant, to exist with no distance whatsoever. But the worshipper before the altar would almost seem to be in the void. And so it is necessary to go out and search for the limits of this void. But not by thinking about a tabula rasa. Because the configurations exist—they cannot be abolished. This implies, then, a decomposition of the figures; a rounding out.

Observation: I want to draw my friend, who I know very well.

I make such an effort to draw the nuances of his unique gaze that I am unable to bring his profile to a close. It is a decomposition. But if I want to draw it entirely with his nostrils then you would say that it just isn’t worth it. It’s pointless. But it doesn’t work that way with architecture. Which is not about a point that emerges from the work but the entire work. In this sense the work is the result of a multiple decomposition.

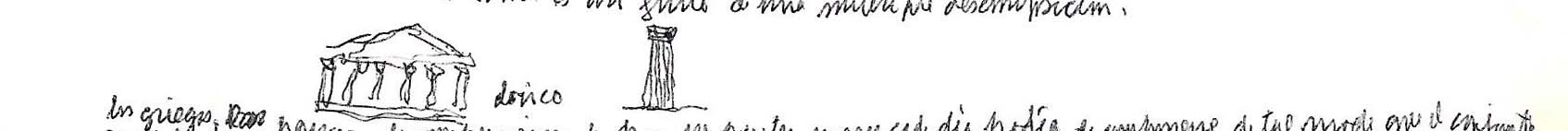

The Greeks, it seems, decomposed the work in parts, in which each day it could decompose in such a way that the whole work ultimately decomposed in the same way. But there is a freedom of forms that Kandinsky introduced, in which each

element creates its own mode of decomposing. And the decomposition of figures begins to multiply infinitely. Which is impossible. And so it makes sense to round out.

b. In the Los Pajaritos work, the decomposition that occurs is one of light, it’s the rainbow. It is the light that has become a line. Yes. Because all decomposition is about turning the here-here and the here-there into lines. And the line is a sketch. The line is steps. The line is the outstretched arm.

If the architect becomes that dispossessed person who possesses the rituals previous to inhabiting, he possesses the line. But he possesses it partly. Because he possesses it in his mind, in his steps. But he does not yet possess it in the work embodied in the natural visible, space. The dominant belief holds that the architect has no trouble at all taking what lies inside—in the heart, in the head—and incarnating it in the line. Because of the natural, visible space, the materials, the technical procedures, the practical organization allow him. No. The natural, visible space is not the friend of these things. Nor is the sun. At best they are indifferent.

Observation:

While sunbathing on the beach in summer the bodies are eaten away by the light. The natural, visible space eats away at everything. Even if we don’t realize it. Or if, when we round, we don’t care.

So you must build lines that cannot be eaten away.

c. In the Pajaritos work the lines are all decompositions of the figure that function in the same way, as if they all had to help each other. To this end they are indistinguishable from one another. And the results of this is a recomposed cube. The rounding of a cube. But precisely because it is the result of this operation it is neither figure nor form.

But the ‘in the presence of’ is something that is satisfied with the ‘here’ of the chapel and the ‘here’ of the city. This is the reference:

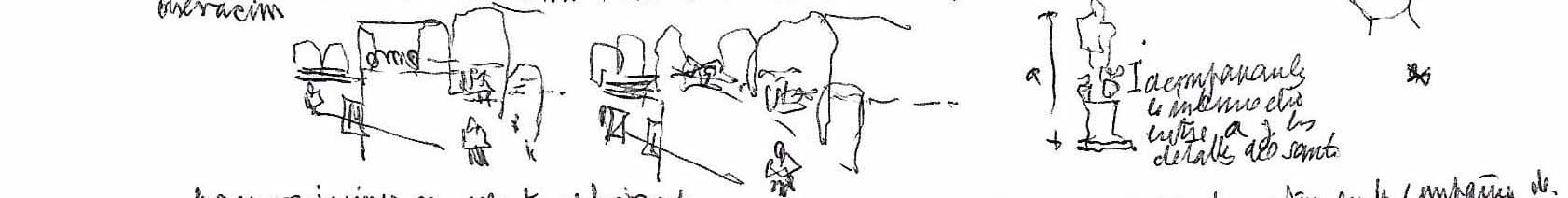

Observation: These dispossessed people, who possess rituals when they remain in the central parts of the cities, reach their rooms through spirals. It’s that the door pivots to distinguish him from the desolate ‘here’.

The Los Pajaritos chapel, going back to Act B.3, decomposes both modes: the Spanish vision and the pivoted vision.

In which the exterior chapel is with and without pivot. Within the foundness of the frontality of the city.

It’s that frontality inherently recomposes in the same way as lines do. And in this vein the entire chapel recomposes in the sense not of the ‘here-here’ but the ‘here-there’ of Santiago.

And so I could have concluded:

Then the Los Pajaritos chapel chose the singular system of frontality.

d. And it proceeded that way because it believed that the semi-darkness rounded out; in a rounded semi-darkness it is not possible to remain in the presence of frontality.

But in the presence of that act of remaining in a configuration.

But the semi-darkness remains as something inside the mind and the heart. And something not embodied.

This recomposition can only materialise because of annoyance and modesty. See.

Annoyance functions through comparison. Modesty has nothing to do at all with comparison. But as it was said in B.5, that is the elusive thing that signals the restorative act of inhabiting. But we verify that the man in the church tends to maintain a pallid, if not soft posture.

It is a posture that tends to be unique.

Of course the horizon tends not to change. When I distinguish

Observation

The non-variations with an act on the horizon

But these non-variations imply the following demand: to be accompanied.

To be in the company of.

Whether of the elements of liturgy or devotion. Or altars, or the arts of the building itself.

Here that human condition of being accompanied manfests itself.

- Now, this fact of being accompanied in the modern world is in a here-here and a here of the city, in which it is not compressed – it is in the expanded.

Cars, elevators allow things to expand.

The construction and the production of the edification converge upon this expansion.

It turns out that this chapel is the smaller dimension of the expanded that manages to shelter, to provide a space for that unique posture of that flexible horizon.

And precisely because of its size it is built with that semi-darkness that does not stand before the frontality as is pointed out in C.4.

- It is for this reason that the work is built in this way.

But one might ask: why didn’t you rely on what has been seen and created by those who have found or who find themselves in similar or identical architectural situations? Who react in the following manner:

el acto único del horizonte flexible (the unique act of flexible horizon) / en los tamaños expandidos de hoy (in today’s expanded sizes)

All of these access points arrive at semi-darkness.

If they all formulate a discourse like this one, that acts in the presence of poetry.

Answer

All configuration of the natural, visible space delivers something or a lot, whether it involves the column, the dome, the courtyard, the plaza, etc. But this is not the whole of the work to be done. There is always something left over, that has not been fully exhausted.

To do something in the presence of poetry is to experience poetry.

D. Execution

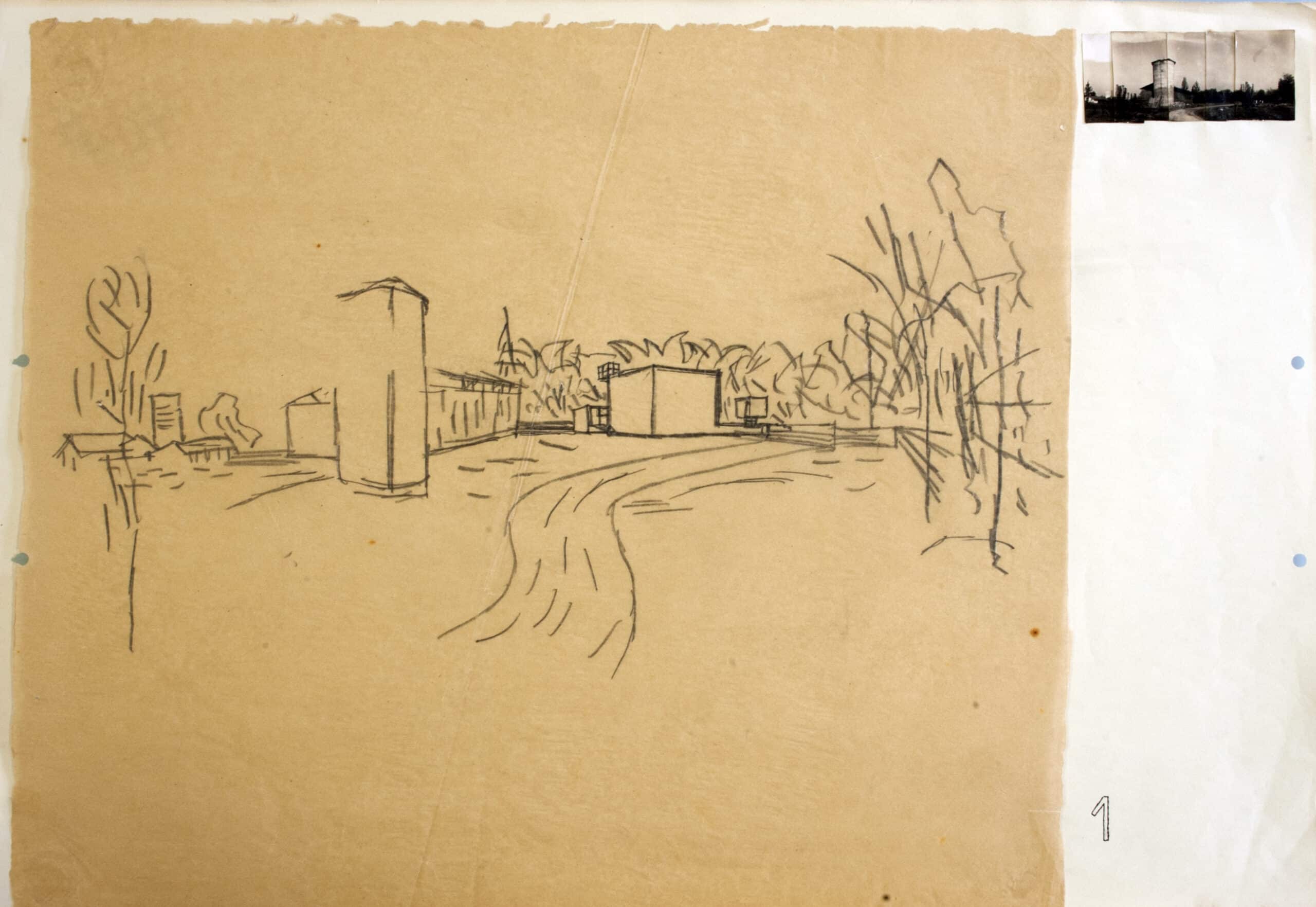

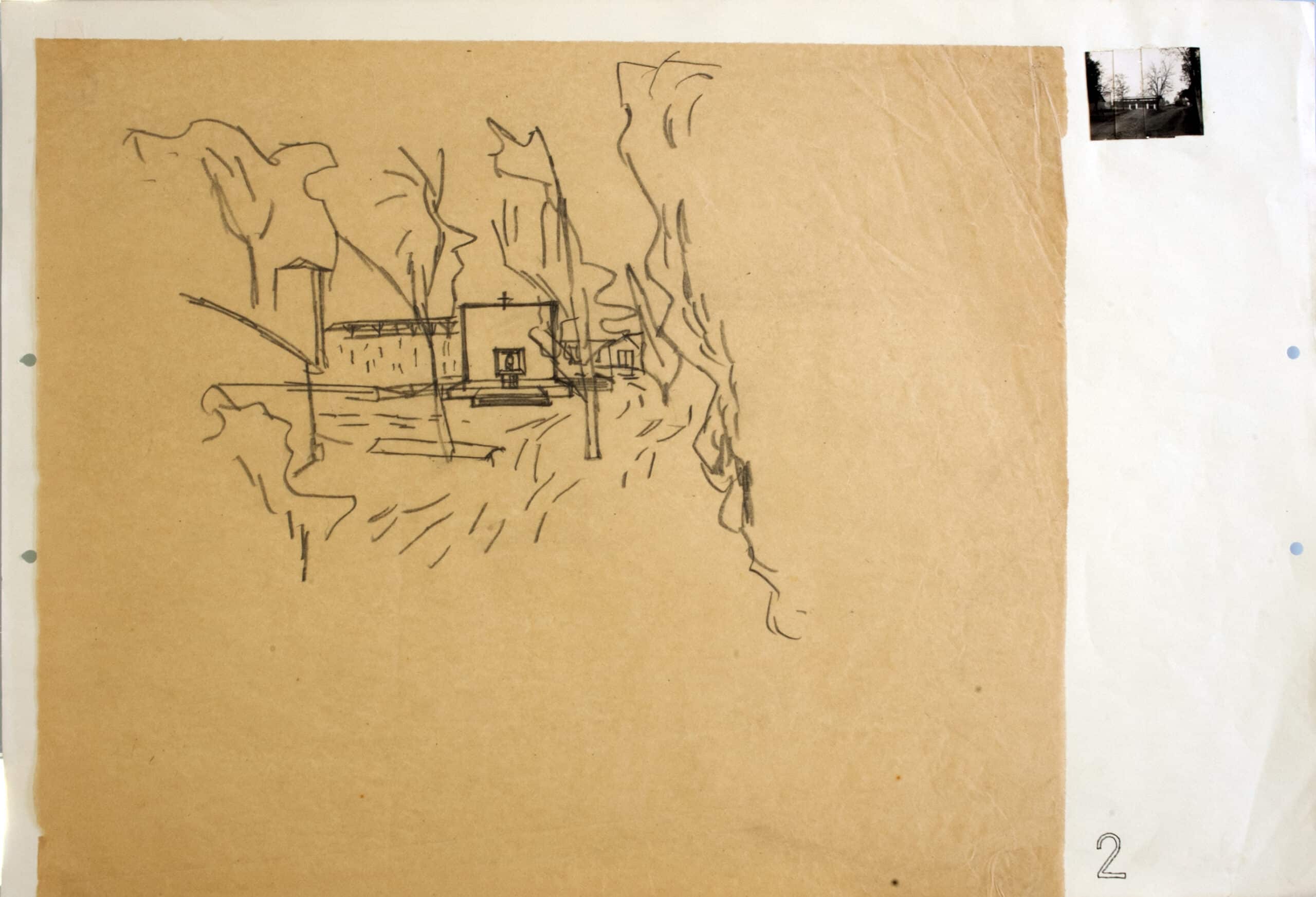

1. A chapel on an agricultural property, as in this case, cannot ask anything to stop or change. Rather, its execution must integrate into the everyday activity of the agricultural work, through a kind of domestic wisdom.

And so the work cannot be

It must be another place to be, another room. A kind of village.

The work evolves in this domesticity of materials, constructive-productive procedures with their corresponding budgets.

2. All of this gives the sizes that this work will remain with and within.

And for this we observe the place in the place itself.

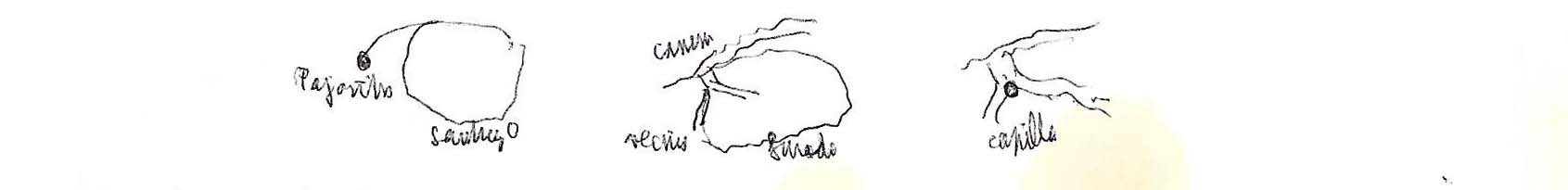

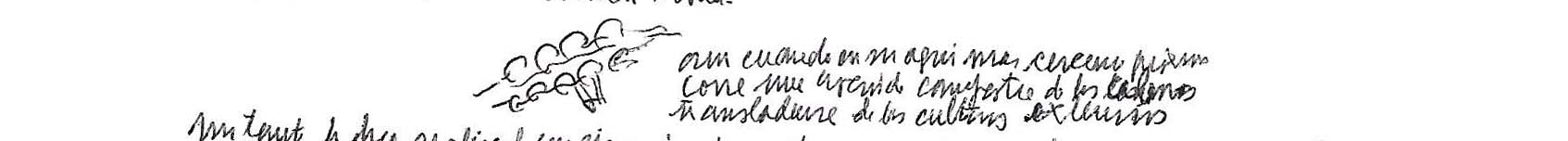

The place belongs to that strip that surrounds sprawling cities. It is no longer what is called countryside. It does not come together as a geographic basin. In other words, a distinguishable system.

That system is delimited like an island

larga cuenca de la cordillera (that would connect this island with the long basin of the mountain range)

And thus the location comes to be something like a plinth.

In this plinth setting, in which that persistence that characterises a basin, an island, no longer (xxxx) tangible or perceivable, is where the work is built.

campestre de las laderas trasladarse de los cultivos extensos (even on its nearest side, there’s a hillside country road that crosses to extensive fields of crops)

In as much as the work, executed as a domestic project, must detach itself from its existence as a country estate immersed in nature; for that reason the sizes are autonomous in terms of their perfection and (exactitude), like the sizes of the lines see C.2.

In which the perfection speaks of the act (B); and the exactitude to the incarnation of the form C

3. This is how perception and exactitude speak of form. It is no longer freedom to choose. Without freedom without any other choice but to…

This text has been excerpted from Alberto Cruz: Proyecto, Obra y Ronda (Chile: Fundacion Alberto Cruz Covarrubias, 2021), p. 17 – 27. Drawing Matter would like to thank Sara and Tomás Browne for giving their permission to reproduce the text and illustrations, and for their assistance with the translation.