Denise Scott Brown ‘From Soane to the Strip’

The following text is an excerpt from Denise Scott Brown’s 2018 Soane Medal lecture, written by Thomas Weaver, and developed out of a series of conversations between Denise Scott Brown and Thomas Weaver in July 2018.

I have never thought of myself as a photographer, only an architect and urbanist, but for seven decades I have taken photographs and used photography to illustrate the ideas behind what I teach, design, and write. These reflect so much of who I am.[01] In the 1950s and 1960s serious, artful photography was black and white and colour photography was used to document reality—this suited me just fine. Reality comes first for me. I’m happy too, when people respond to my buildings and photographs with a direct, ‘Gee, I love it’, but I hope they will also react to another challenge—to Le Corbusier’s cry against ‘eyes that do not see’. My own wayward eye is a consequence of early influences, including Corbu’s, and I learned from a young age to follow the ‘just take it’ principle. Act quickly! If you stop to ask yourself why you want it, it’ll disappear before you reach it, and just as you realise why you wanted it. It also derives from an inner iconoclasm, a fascination with rule-breaking. Or you could just call it mannerism. For this reason, I am especially pleased that this lecture comes to you through the benign patronage of John Soane. Through it, I hope you will see not just how and what I learned from him, and the strength of our affinity, but how his own eyes was just as wayward.

[…]

[A]s my interests widened, I found more reason than ever to photograph, not least because I was doing so to teach. Through a joint appointment in architecture and planning, I taught studio and courses in both departments. Penn had a good collection of architectural slides, but I could augment them with African and European examples of folk and pop, industrial buildings, 1930s architecture and vernacular, squatter and mass housing. For Philadelphia I had slides of industry and warehouses without end, together with the city’s industrial gateways and a growing collection of aerial views. These, plus city physics and the concept of ‘linkage’, took my teaching and photography toward patterns of life in the city.

Walking around, I shot combinations of jeans in a park, a row of bottoms sitting on the side of a fountain, and white sheets strung in lines filling the backyard of a neighbourhood laundry, forming a weird visual alliance with the long white car parked beside them. I was also drawn to Philadelphia street life, its colours and architecture, and the dangers of crossing the road.[02-05] At the same time I explored the housing stock in neighbourhoods rich and poor. [06-09] Philadelphia colonial townhouses were Georgian but built of bricks more finely wrought than the London yellow stocks—though I love these just the same. In the late nineteenth century Philadelphia was so rich that its workers could afford to own their houses. The row house stock, built in vast, electric street-car districts, showed flights of fancy surpassing the Georgian, and urban infrastructure far beyond present needs—for instance, some granite paving slabs in the old city measure 3 x 5m—and the clashing scales and styles of the Industrial Revolution still break the orderly systems of architecture.

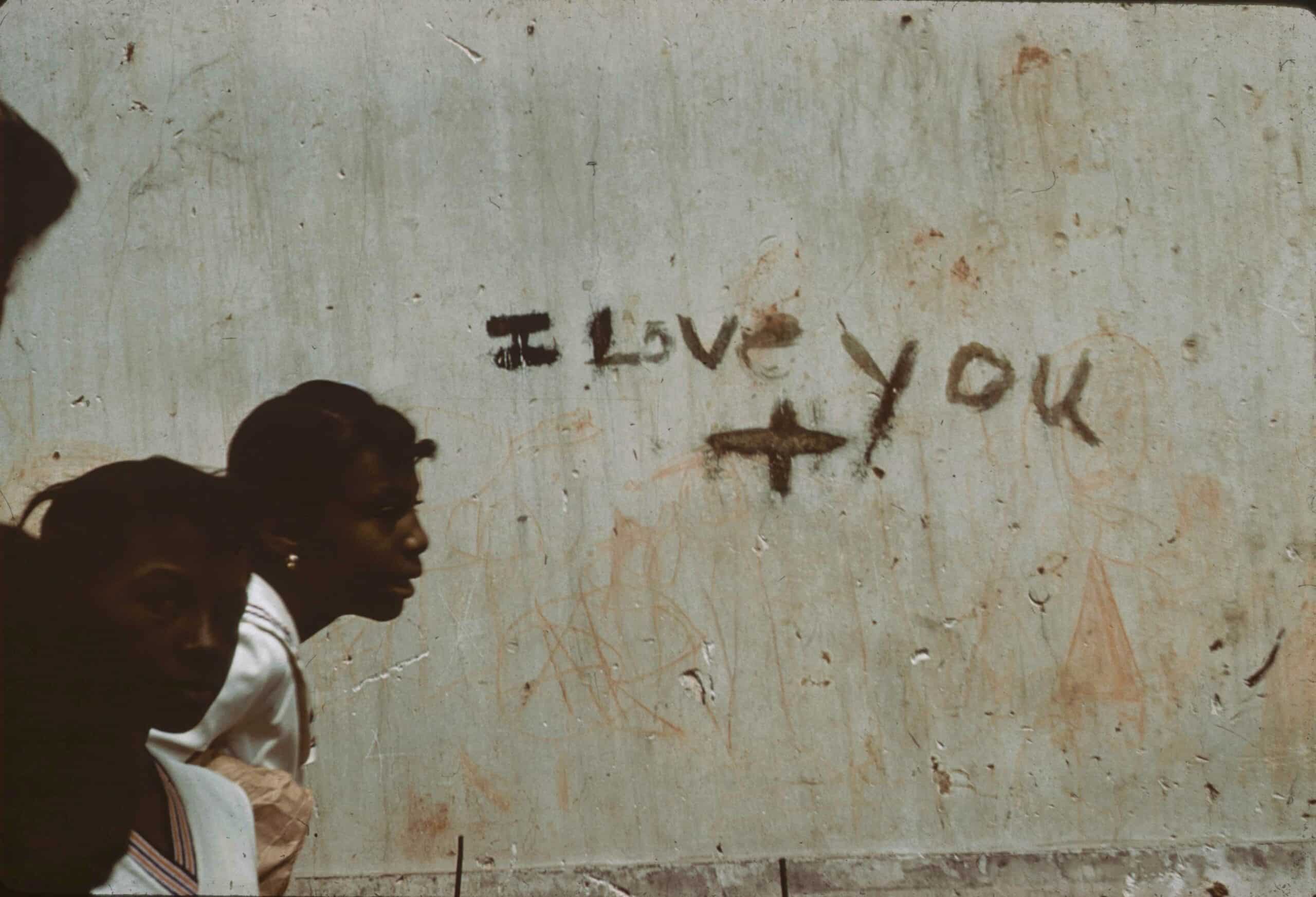

I also looked for mannerist juxtapositions that brought a messy vitality and perhaps its own order to the everyday city. As ever, the ‘just take it’ principle meant that I pointed my camera and clicked. Over two summers I worked for the Philadelphia Neighbourhood Garden Association, an alliance of matriarchs, main-line aristocrats and inner-city grandmothers, who shared values on the role of window boxes in the lives of people. And in blocks where this collaboration was successful, behaviour changed. Studying them gave me unusual views into the city’s low-income districts. I discovered, for example, that neighbours working to improve their block would paint the curb-stones white—one told me, ‘it’s like putting on lipstick’. But go there now and 70 years later another gentrification has brought the middle class. Look carefully and in small corners you may still see a little white curb paint. It’s a precious relic, but does anyone know what it means? In the same inner city district I discovered this piece of graffiti and, thinking of Cartier-Bresson, clicked at whatever passed by and hoped for a small miracle.[10]

[…]

My first visit to Las Vegas had been in April 1965, and before I even reached The Strip, driving through the Mojave Desert, I was reminded of South Africa.[12] The city itself also had echoes of my parents’ love of funfairs and resort towns, like Coney Island and Vegas itself, which they had visited in the 1940s, as much as my own early South Afican fascination with roadside vernaculars and pop cultures. Moreover, Las Vegas resonated with ideas I had learned in London from the Smithsons, with The Strip in effect being a very large as-found object. So my interest in Las Vegas was not a sudden infatuation but something that had been with me a very long time.

Driving The Strip for the first time I knew it was important, even profound. I also felt that it was ideally suited to take on the philosophies and methods I had derived from planning, and the architectural theories I continued to develop on a mannerist base. What I didn’t know, but hoped, was how much fun it would be, because Bob and I had a great time with our Yale students, analysing and documenting the city in a million different ways—through drawings, sketches, leporellos, stills and films, and through studies of its hotels, casinos, wedding chapels, gas stations, parking lots and signs, and in polemical provocations about its monumentalism and in all of its ducks and decorated sheds.

But none of us thought it would have such an effect. Perhaps we were just too busy looking. Or rather surveying the city through the windshields of our rental cars. And as we worked, relations between public and private started to reveal themselves, or the tension in Las Vegas between the physical and the social, formal and informal, seeing and perceiving, and between all those activities that showed up in the patterns and forms of the city. In photographing Las Vegas I also noticed how the big black Strip foregrounded almost everything. Tarmac became its own kind of campo—yet another Soanean inversion.[13-17]

The whole lecture can be found in the form of a publication Soane Medal Lecture 2018: Denise Scott Brown here, and a recording of it here.