Design Drawings Damage Atlas (2023)

Snap, crackle, pop.

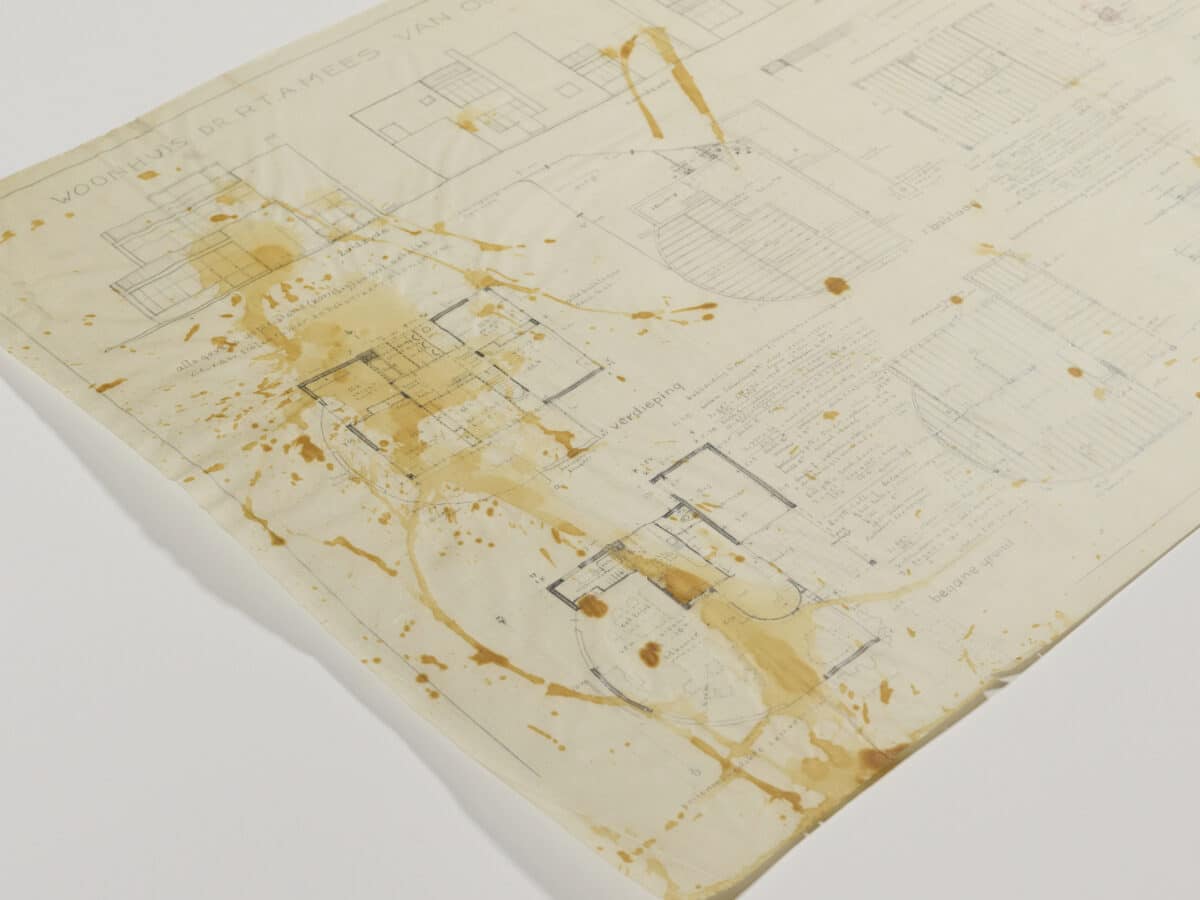

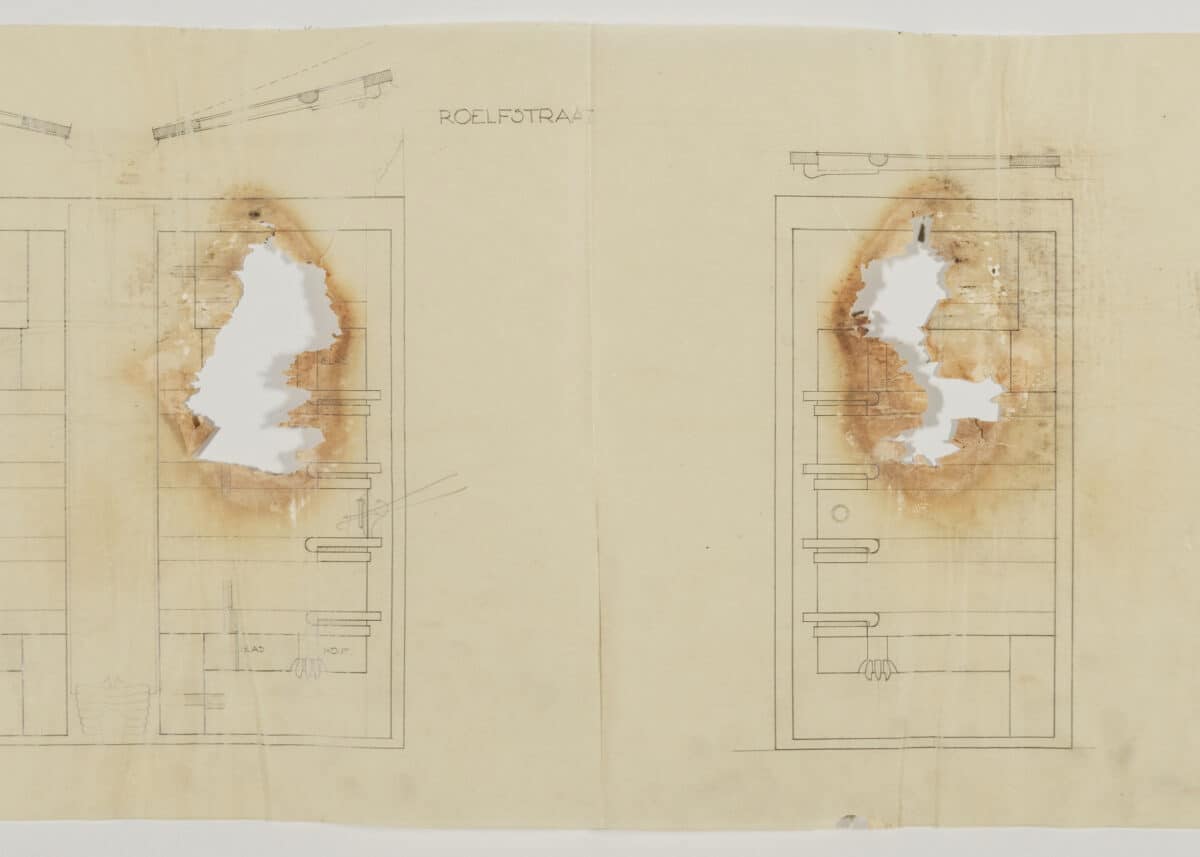

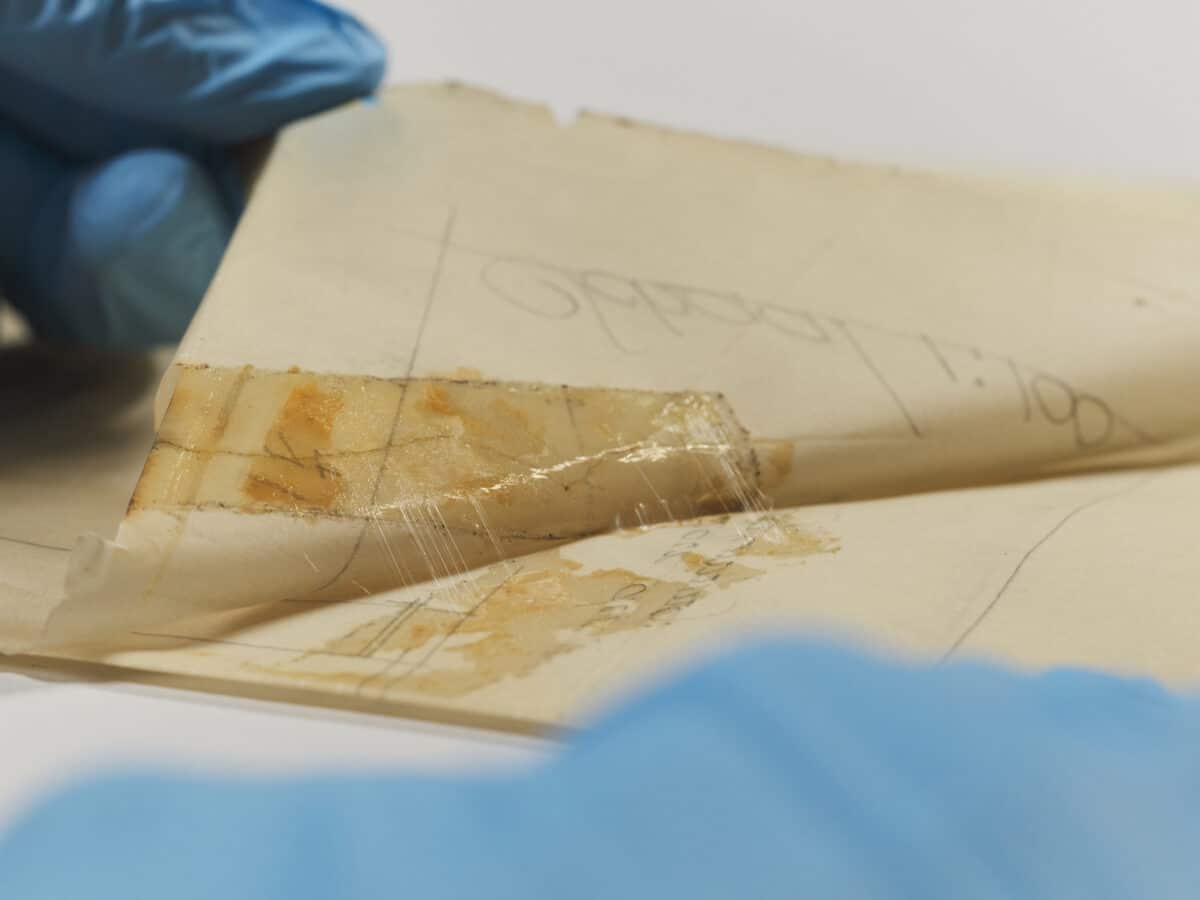

Oh, that horrible sound of unravelling a roll of architectural drawings on old dried-up tracing paper from the nineteenth century. Slowly unfurling the brown brittle sheet, it cracks and shatters, little bits drop off in flakes, littering the table and floor like confetti. The experience feels like cooking fish en papillote: taking it out of the oven, the pliable fresh white cooking parchment paper you wrapped the salmon in is now dark and desiccated, splintering to the touch. The oil or resin in the paper has dried out.

The fate of old tracing paper is but one of the many woes that can befall architectural drawings. In architectural collections, these problems have to be dealt with, by curators and paper conservators. Although serious, damaged drawings are nothing compared to the much feared worst-case scenario… total destruction. When I was a curator at the Royal Institute of British Architects Drawings Collection when it was in Portman Square, I was asked to put together the collection’s first-ever disaster plan, a depressing job. We sat around the kitchen table asking ourselves what would we save first if a fire broke out. Most of us immediately thought of the several hundred Renaissance drawings by Palladio. As those were the days before computer records, when catalogue cards for each drawing or set were kept in a large card catalogue cabinet, our chief curator Jill Lever wisely replied: save the two accession books in which we recorded all new acquisitions, that way we would know what had been lost. After that, as these leather-bound volumes were kept behind my desk, I was always ready to throw them out the window at the first whiff of smoke.

For less drastic examples of damage to architectural drawings, although there are still enough cases to make your toenails curl, comes a new publication, at the affordable price of free online. Created by that outstanding national collection of Dutch drawings, the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, until 2013 called the Nederlands Architectuurinstituut, the Design Drawings Damage Atlas, presents examples of non-criminal crimes of assault and battery in their archive to paper dating between 1870 and 1990. This is the third publication initiated by Metamorfoze, the Netherlands’ government-subsidised programme for the preservation of the country’s document heritage and follows reports on book and archival damage.

This new reference work is aimed at the non-technically trained holders of architectural drawings. Although there are hints on repair, this is more about identifying what the problem is and how it came about. Are those grazing marks left by beetles, or gnawed holes by mice? Was that warped and curling drawing left too near a radiator or, on the contrary, in the damp? Folds, tears, dirt, discolouration… the damage list and gory photos march on like entries in a medical textbook about skin diseases.

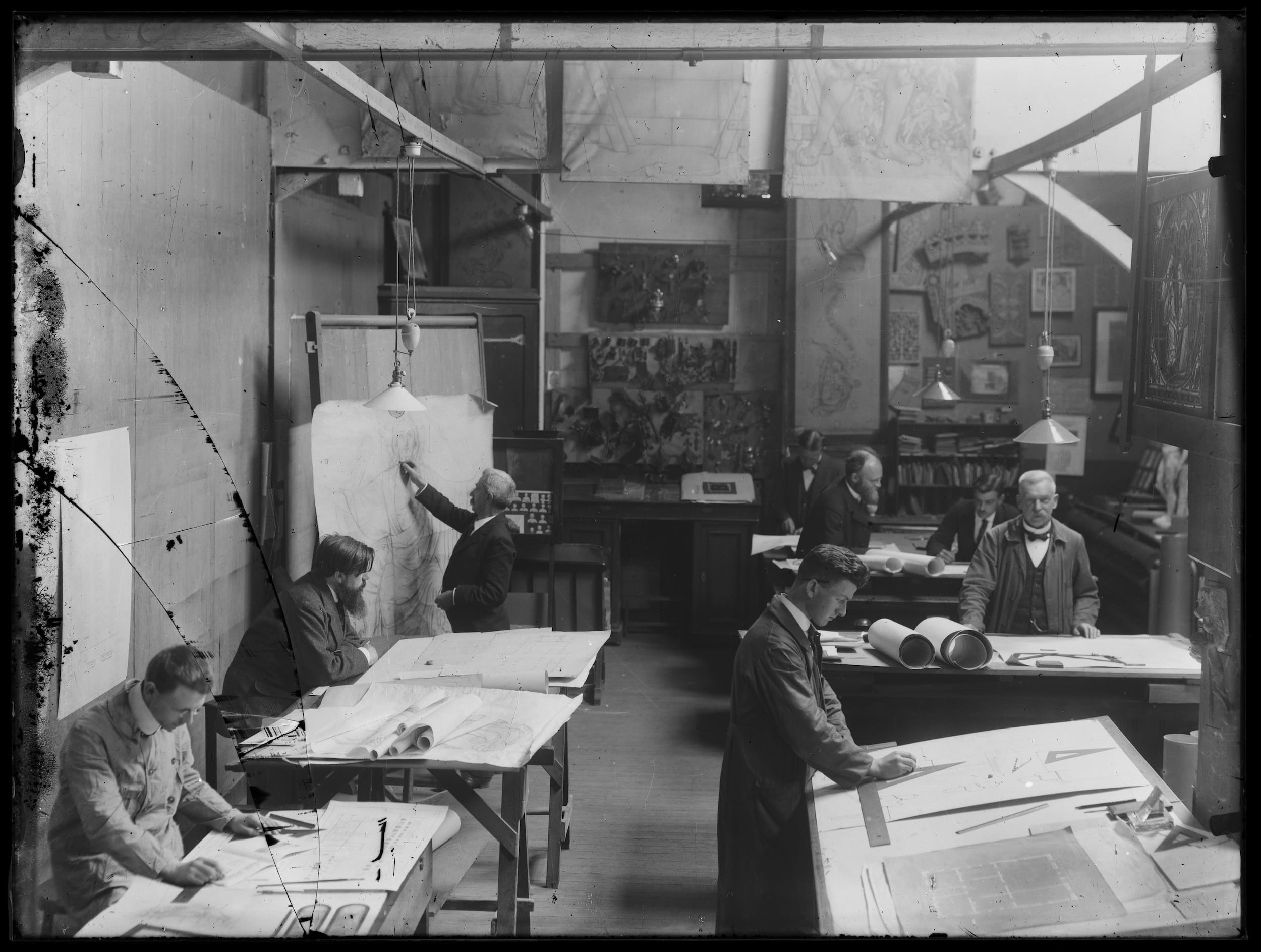

From the mid-nineteenth century, reproductions formed the greater proportion of paper output in the offices of architects, and thus dominate many of today’s architectural archives. Much of the Damage Atlas is thus given over to facsimiles because to understand the damage to copies you must understand the why and how of the major techniques of photographic reproduction. This is a skill not only useful to curators but important for all those who study, talk, or write about architectural drawings produced in the period under examination. Not to be acquainted with the composition of the drawing support is like a food critic commenting on a restaurant dish and not knowing one of the main ingredients.

Although many different types of copying processes came and went, the ones that emerged on top were the blueprint, whiteprint, diazotype, and electrostatic copies. Developments in copying revolutionised office practice and followed technological and commercial innovations, freeing the architect from the laborious requirement of making copy drawings one at a time.

At the RIBA Drawings Collection in the 1980s and ‘90s, when sorting and weeding a new acquisition, the policy was only to keep a copy drawing if the original was not available; copies, for obvious reasons, being considered inferior to the original unless they were hand annotated, thus adding more information. However, sometimes I balked. How could I bin a Marcel Breuer copy of one of his furniture designs just because the original had also arrived in the set? It felt like sacrilege, so I would keep them, thinking along the lines of possibly one day a researcher would come in, interested in Breuer’s working methods, or placing original and copy side-by-side in an exhibition.

Perhaps curatorial discretion should have been added to my RIBA disaster plan, because no doubt many treasures have been disposed of by curators. The pressure of storage space is always looking over the curator’s shoulder. And it was not until the latter part of the twentieth century that architectural drawings were considered of artistic, academic and monetary value, before being simply thought of as benign working documents, of vague interest and expendable.

One final example from my RIBA Drawings Collection disaster plan, a contingency to be put in place if there was a bad fire: what to do with the drawings if soaked by firefighter’s hose water, a subject raised in the Design Drawings Damage Atlas. One of the best courses of action is to freeze them as fast as possible, putting them in stasis for later assessment. So dutifully I trooped across the street to the Portman Hotel and persuaded the management to allow us to use their walk-in kitchen freezer if need be. The head chef took me to see it, a vast room with the walls lined in metal shelves, perfect for the job. And even more perfect, it was empty except for a single cheesecake. I asked him, why it was bare, and proudly he replied, ‘Because we only cook with fresh ingredients.’ Thankfully, our drawings never had to join that frozen cheesecake.

Neil Bingham is former curator of architectural collections at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Royal Academy of Arts, and Royal Institute of British Architecture. His latest book is on the modern British architect Patrick Gwynne (1913–2003), and when he catalogued all of Gwynne’s architectural drawings for the RIBA, none were harmed in the process and nothing thrown away, while many of the drawings were stuck together by adhesive residue from the title blocks and had to be separated and interleaved with silicone-coated release paper.

The Design Drawings Damage Atlas is a collaboration between the Nieuwe Instituut and Metamorfoze. The digital version of the atlas can be downloaded here. A paper copy can be obtained free of charge from Metamorfoze.