DMJ – Sir John Soane’s Office

Sir John Soane’s drawing offices at Nos 12 and 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields were the fulcrum of his practice between 1794 and his retirement in 1833. His unique surviving ‘upper’ office was restored in 2022–23. In this article, I will trace the history of the office and recount its use as an instrument in the training of Soane’s pupils.

When the young architect John Soane bought No.12 Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1792, he demolished and rebuilt the main house as a home for his family, designing a single-storey purpose-built office at the back, accessed from a mews street, Weston’s (today Whetstone) Park. In this new working space Soane’s articled pupils were supervised by one or more clerks and the office drawings and business papers were housed.

At some point, probably in either 1803 or 1806, this first office was expanded by the addition of an ‘Upper Office’ above, accessed via a wooden staircase.[1] 1806 seems the more likely year, for not only did Soane have a larger number of pupils and clerks then but he also required more space for the production of drawings following his appointment as Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy in March.[2] Although he didn’t actually deliver his first lecture until 1809[3] he began preparatory work immediately and in May started his pupils on the production of lecture drawings. Henry Hake Seward worked on a ‘Drawing from Sir William Chambers’[4] while a day or so later two other pupils were busy with drawings ‘from Vitruvius’ and ‘from Palladio’ and another started work on a drawing of the entablature of Soane’s favourite Roman building.[5] The production of lecture drawings remained a mainstay of the pupils’ work for the remainder of Soane’s career.

The appearance of the Lower Office is recorded in two watercolours made in 1808 (Figs 1, 2), one of which shows the staircase to the Upper Office. These reveal the extent of built-in storage for records, including full-height cupboards. A plan chest in a recess created by two cupboards (on the right in Fig.2) is shown with deep drawers at the bottom, probably used for bundles of documents. A clerk could have worked at a drawing board resting on the top of this plan chest, either standing or seated. Although we have no view of the Upper Office, we can deduce that the long drawing tables must have been up there and see how light penetrated down through floor apertures into the Lower Office below.

The two views show plaster casts after antique and Renaissance architecture and sculpture hung in the Lower Office. Several, including the circular salver on the far wall and the female head in the recess on the right (Fig.1), can be identified in the collection today.[6] In Fig.2 we can see a series of small variations on the Greek key decoration—an essential part of the repertoire of any architect of the neo-classical period—as well as a large relief of Minerva.[7]

In 1807 Soane negotiated the purchase of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the house next door, and the following year, 1808, redeveloped the rear premises as an extension to his existing house at No.12, pulling down a stable block on the site. Here he built a ‘plaister room’ for the display of plaster casts and fragments (today the Dome Area) as well as new lower and upper offices. In 1812 Soane took over the whole of the No.13 premises, pulled down the front part of the house and rebuilt it, connecting it to the new area at the back and blocking off and renting out No.12. Soane then lived at No.13 until his death in 1837, when his home became Sir John Soane’s Museum.[8]

Although we have no views of the new Lower Office behind No.13, two design plans from the construction period (1808–09) record its basic elements (Figs 3, 4). On both plans the office is to the top right. It has an entrance opening on to the street and incorporates a staircase that runs north–south behind the solid east wall of the adjacent ‘plaister room’, giving access to an office on the level above. Fig.3 shows the initial layout in August 1808 with a desk and chair beneath the south window of the office, probably for a clerk who could supervise and be ready to meet visitors, whilst the pupils worked upstairs. In Fig.4, dated March 1809, a modified layout is proposed with a ‘writing desk’ shown alongside a large bookcase flanked by cases for drawings. Soane owned multiple copies of important architectural texts ranging from Vitruvius’ treatise to those of contemporaries such as William Chambers and it seems likely that he allowed his pupils to study them. [9] Both plans show that a servant’s bedroom, close to the back door, was incorporated within the Lower Office, probably in part to ensure security at night.[10]

In 1812 we get our first glimpse of the top-lit Upper Office behind No.13, with long desks each side (Fig.5). The perspective is not perfect but a void beyond the far desktop and a glimpse of the top of an arch indicate that the office is a space within a space. When this view was made, Soane was busy rebuilding the main house at No.13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Disassembled Kent tables stacked under the desks perhaps hint at his being in the midst of this. Perched on a ledge above the desk, to the left, are three small models (the middle one is of the façade of No.13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and the one on the right is of the portico of the Royal College of Surgeons on the south side of the square) made for the court case Soane fought concerning the façade of his new house in 1812.[11] Two do not survive but one, the small façade model for No.13, is now back on show in the restored office, displayed as at the time of Soane’s death in 1837 (Fig.6). Further to the right are other small models for attics at the Bank of England. These are of the sort routinely produced to present alternative designs to clients.

Soane’s offices behind No.13 were remodelled extensively in 1818 when the Lower Office was converted into additional display space as a consequence of his purchases of antiquities and casts at the Robert Adam Sale.[12] The Upper Office was modified again in 1821 when the roof was raised and the staircase up to it moved to the east end. Fig.7 is a sketch in Soane’s hand, capturing the idea of the Upper Office as a table-like platform within a larger space, supported by columns in the colonnade below and showing how light from the skylights falls not only on the desks but also illuminates the spaces below the office.

Fig.8 is the only other view of the Upper Office from Soane’s lifetime, by Joseph Michael Gandy (1822). It looks from the top of the stairs up to the office towards the Dome Area (glimpsed through the aperture at the far end) and renders the drawing office as a trompe l’oeil drawing, as if on a sheet of paper curling up at top and bottom. Since 1812 the space under the desks has been infilled with many additional drawers and cupboards—no doubt the consequence of the loss of the Lower Office a few years earlier.

One final alteration to the office was made in 1824–25 when Soane rebuilt 14 Lincoln’s Inn Fields and expanded his Museum across the back of that house. The staircase up to the office was relocated to the north end of the new ‘Museum Corridor’ (Fig.9), where it remains today.

A total of 54 men worked in Soane’s office as pupils, clerks or assistants between 1784 and Soane’s death in 1837, six days a week, initially from 7am to 7pm in the summer and 8am to 8pm in the winter. After 1810 this changed to 9am to 8pm as standard year-round office hours. Most were pupils articled for five years for a £157 premium – their articles promising that Soane would educate them in the ‘Art, Profession and Business’ of architecture. The earliest of these documents concerns Soane’s first pupil John Sanders in 1784, requiring that the new pupil ‘shall faithfully and diligently serve him [Soane] … his secrets keep and his lawful command obey and conform, he shall not part or absent himself from the service of his said Master without his leave during the said Term or unduly or negligently spend or waste any of his said Master’s property.’ A clause which was only relevant to Sanders, who lived with the Soane family, bound Soane to ‘find and provide … good and sufficient meat drink and lodging’. All later surviving articles stipulate that the parent make provision for ‘proper and sufficient board, lodging, washing and apparel’ and at present we know very little of the pupils’ lives outside office hours. David Laing’s articles of 1790 state that the pupil ‘shall not unduly spend or waste any of the Monies, Goods or Chattels of the said John Soane nor any of his Employers [clients] which shall be in the custody of or intrusted with him, but shall at all times during the said Term truly account for, pay and deliver to the said John Soane … all and every such sum and sums of Money, Plans, Draughts, Accounts, Writings, and other things with which he be intrusted’. This expansion of the previous wording reflects how regularly pupils were placed in a position of trust, couriering money and drawings to and from clients and contractors and taking responsibility for entering and reconciling accounts.

The pupils arrived in the morning at the back door of the office (Fig.10), entering close to the stairs up to the office. At no time did they use the front door and they were not permitted to go to the kitchen or fraternise with the servants—as a letter from a pupil apologising for an infringement in 1800 reveals.[13] Soane himself did not work in the office but had his desk in the ‘Little Study’ nearby on the ground floor, with a small dressing room and water closet between that room and the office providing facilities that he could use before going through to the office to see employees or meet a visitor.[14]

As pupils entered the office each day they were greeted by a model of the classical orders set on a balustrade (Fig.11). New pupils usually spent their first few weeks drawing the orders and this model was a reminder of their centrality to any architect’s training. The arrangement is a typically idiosyncratic—even humorous—Soanean riff on the nature of the column, the formality of the orders contrasting with the freely inventive variations on the ‘column’ represented by the barley-twist balusters. On the adjacent wall is a full-size model of one of Soane’s own inventive neo-classical pilaster capitals for the Bank of England.

The pupils’ names and times of arrival, along with a note of work done, were entered daily in the Office Day Book.[15] In accounting, day books were in common use as early as the 16th century, a ‘day book’ being synonymous with a ‘journal’ and providing a chronological account of money coming in and out. However, in Soane’s office the day book had a broader function, recording the entirety of daily business. Some financial transactions were included, which would later be entered into a ledger or journal (one job done by pupils was to reconcile the two). Soane Office day books survive for an almost unbroken run of 45 years, providing an extraordinary window into his business practice (Fig.12).

They record the pupils producing copies of drawings, done by pricking through the outlines on to new sheets of paper or sometimes by tracing, amending them to incorporate Soane’s scrawled corrections as designs evolved. The pupils also ran errands, received deliveries, went on site visits, mounted and framed drawings for Royal Academy exhibitions, entered accounts and wrote out invoices. They were permitted days off at Christmas and Easter and Soane allowed a Jewish pupil—David Mocatta, whose name appears on the pages reproduced in Fig.12—not to work on Saturdays.

Once in the office the pupils worked at long mahogany desks—built from salvaged elements from the previous office at No.12—with a good north light falling on their drawing boards, which probably rested on the front edges of the desks.[16] We know they sometimes perched on stools because the 1837 inventory lists ‘3 Stools covered in leather the seats stuffed with Horse [i.e. horsehair]’.[17] Grated apertures below the desks enabled heat to circulate from Soane’s innovative central heating system without the need for a fireplace (the key to the viability of the inventive structural form of the office) and also enabled every word said to be heard from adjacent spaces—an incentive to disciplined, quiet work!

Pupils sat under the watchful eye of the Roman Emperor Lucius Verus, a cast of whose face is the only human presence among all the casts in the office (Fig.13). This seems no accident as he was famed as an exceptionally good student.[18]

Only a few of the drawing instruments used in Soane’s office survive, including pens with metal nibs, mass-produced in England from 1822.[19] Quill pens were bought in bulk (500 at a time for a few shillings), probably already washed, dried and trimmed of much of the feather itself, and would then have been cut and shaped to form a nib using a quill cutter, a task that was part of the routine of daily life of the office. Three surviving ink-stained quills are a tangible and evocative link with the pupils and the survival of these implements a miracle of serendipity (Fig.14).

Pupils were thoroughly trained in draughtsmanship and the day books record some attending classes at the Royal Academy or being sent to private tutors. The casts on the walls of the office provided subject matter for drawings, fostering familiarity with classical ornament (Fig.15), and the pupils also undertook exercises such as ‘drawing shadows’, requiring the casting of strong shadows using lamps or candles (Fig.16). Intriguingly, during the restoration of the office, one framed cast of egg-and-dart moulding was discovered to have burn marks, although no fire is recorded there (Fig.17).[20] Perhaps a naked flame got too close?

As well as working in the office, pupils were sent out to learn about construction processes through making progress drawings on site (Fig.18) – a method in architectural training that seems to be unique to the Soane office.

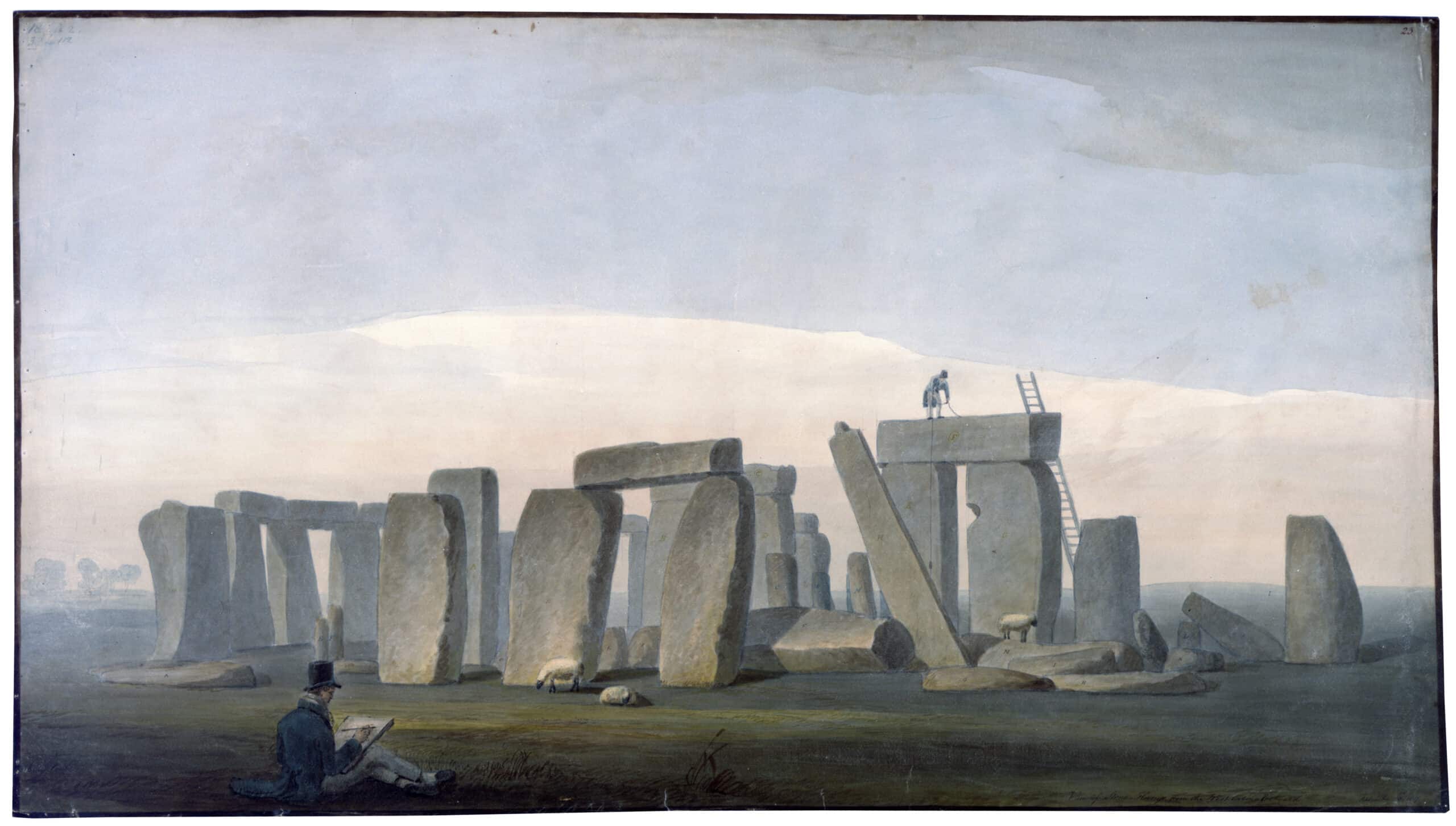

Soane’s pupils also produced more than 1,000 watercolours to illustrate their master’s Royal Academy lectures. Some exceed 6 feet in length—their production making full use of the long desks in the office. These too could involve work elsewhere, as when a group of pupils were sent to survey Stonehenge in 1817. Henry Parke produced the watercolour shown in Fig.19 with its delightful vignette of one of the party (himself?) sketching the scene. Parke also accompanied Soane on a ten-day trip to Paris in September 1819 and made sketches for a series of exceptional lecture drawings illustrating the city (Fig.20). When Parke left the office, Soane gave him a gift of £100, which enabled him to travel to Italy, Sicily, Greece and Egypt from 1820 to 1824. For many of Soane’s pupils, like Parke, their time studying in Soane’s office provided, in the words of Edward Davis, ‘a passport … through life’.[21]

The restoration of the office completed earlier this year enabled us to learn more about the construction and use of the space. It involved the removal of almost 200 casts from the walls for cleaning, revealing that many had never been taken down and were still held up by their original long hand-forged nails. Our conservators carefully prised the casts off, removed and straightened the nails and a year later re-fixed the casts with the same nails using the original holes. Fig.21 shows the areas of unpainted, bare wood revealed where items were taken down that still occupied their original spaces and had been left in situ and painted around in later redecorations. Our redecoration carefully preserved all this evidence. Over the period of a year the casts were surface-cleaned before their re-fixing in January 2023.

Analysis of the original hang of the office revealed just how many items had been moved elsewhere since Soane’s death and needed to be brought back. Now, post-restoration, it is the reintroduction of architectural models that is most striking, from small wooden models of domes which, after an absence of more than half a century, could be re-hung on their original fixings, still in the beams (Fig.22), to the large models for the Bank of England on the desks (Fig.23).[22]

Examining the desks and drawers during their restoration by Peter Holmes also brought new insights. Most are numbered with ivory discs, the numbers cross-referencing with the lists of drawings drawer by drawer in the 1837 inventories. Some of the drawers down at floor level are unnumbered: perhaps these were used for storing the many reams of paper that the office required. Other elements were clearly constructed from salvaged elements – probably from Soane’s earlier office behind No.12—adapted and carefully reused in the new spaces (Fig.24). A gap beneath a desktop may have been the place where drawing boards were slotted in, out of the way—just where two surviving ones were found in the 1980s (Fig.25).

Soane’s office is, as far as we know, the only surviving architect’s office worldwide from before the late 19th century and is one of the most important spaces in the Museum, largely unaltered since it was used by Soane and his pupils. Its form continues to inspire architects today and we hope that its restoration returns Soane’s busy architectural practice, around which the life of the house must have in large part revolved, to the fore.

Notes

- Unspecified office alterations are recorded in 1802 and 1806.

- Soane Museum curatorial records: spreadsheet of pupils/employees in the Soane office (unpublished).

- David Watkin, Sir John Soane: Enlightenment Thought and the Royal Academy Lectures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 288.

- Soane’s first lecture was about Civil Architecture, the title of Chambers’s famous Treatise on Civil Architecture (1759). Chambers was a founding member of the Royal Academy and someone Soane knew and admired, and it seems a fitting tribute to an early mentor that the first lecture drawing produced would be taken from this work.

- Soane Museum Archives: DB/11: dates in May 1806 with the first entry for a lecture drawing on 9 May.

- The salver is either SM A20 or SM M1044 (there are two casts from the same original in the collection) and the head is SM M813, cast from the figure of ‘Dawn’ on the tomb of Lorenzo Duke of Urbino, one of Michelangelo’s Medici tombs in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence.

- SM M102.

- On Soane’s death on 20 January 1837 the Soane Museum Act of Parliament (1833) came into force, vesting the Museum in a board of Trustees, named in Soane’s Will, on behalf of the nation and requiring it to be kept ‘as nearly as possible’ as it was left at that time.

- Soane owned 13 versions of Vitruvius and multiple copies of Palladio’s celebrated four books of architecture, in Italian and English, as well as six copies of Laugier’s Essai sur l’architecture (1753), in French and English editions, and four copies of Sir William Chambers’s Treatise on Civil Architecture.

- Soane’s first Office at No.12 had an ‘alarum bell’ fitted, which was altered and repaired in 1803 (SM Archives: 16/1/2 and duplicate bill 6/50/9).

- Soane was accused of contravening the Building Acts with his projecting ‘loggia’ on the façade of No.13 and presented the model of his own projecting façade alongside the two others showing projections on other buildings in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in support of his case, which he won.

- Christie’s sale of the ‘valuable collection of antique sculpture … also architectural specimens and fragments, from celebrated remains in Italy; cinque cento carvings, and original compositions in terra cotta, with casts from the same, which were procured at great expense by that distinguished architect, R. Adam, Esq.’, 22 May 1818 and on following days.

- SM Archives: Letter from pupil Charles Malton to John Soane, 23 September 1800, in which he explains ‘my only reason for going into the kitchen was to enquire if you were from home’ and that ‘beyond common civility’ he has never spoken to Soane’s manservant. See Susan Palmer, At Home with the Soanes (London: Pimpernel Press, 2015), 16.

- This had also been the case at No.12, his first home, where Soane’s desk was in the Breakfast Room on the ground floor with a small dressing room and water closet on one side of the central courtyard between that room and the office.

- Sometimes the entries are in pupils’ individual hands but sometimes a clerk seems to have made the entries.

- The front edges of the desk-tops are much eroded and the damage could easily have been caused by this practice. In the AB 1837 inventory a list of ‘Sundry Mathematical instruments, Drawing Apparatus &c. &c, found in different places’ includes four drawing boards: ‘1 mahogany Drawing Board, D[ou]ble Elephant size, 2 deal [pine] ditto Antiquarian size, and 1 ditto [deal drawing board] smaller’. Aside from the small number of instrument cases and instruments for office use (dividers, compasses, T-squares and rules) on the list, the other equipment comprises surveying instruments to be used out of the office (‘A Beam compass, with shifting legs’; ‘A mahogany stand for a Theodolite, in a box’ and ‘A Hollow stick containing a pair of “Five Feet Rods”’). It is interesting that although no museum numbers were allocated to these objects, by including them at all the first Curator of the Museum, former pupil George Bailey, recognised that there was value in their preservation.

- SM Archives: AB inventory, op. cit., 407.

- SM M1400. The cast is from a marble bust in the Louvre (MR 550; Ma 1170) dating from c. AD 180.

- In 1792 ‘New invented’ metal pens were advertised in The Times newspaper. Bryan Donkin patented a metal nib in 1803 and in 1822, John Mitchell of Birmingham began mass-production of machine-made, steel pen nibs.

- SM M1372.

- Letter, Edward Davis to Soane, 30 April 1828, SM Archives Private Correspondence XV.B.23.1.

- It seems likely that these large Bank models returned to Lincoln’s Inn Fields when Soane retired from the Bank in 1833 and were previously in his office there. They could not have been on the desks at Lincoln’s Inn Fields earlier as this would have made the work of the busy office impossible.

I am greatly indebted to our former Director, Margaret Richardson, whose fascination with the workings of Soane’s office practice first inspired my interest in this extraordinary space. This article is dedicated to her with grateful thanks for her encouragement and friendship over the last 40 years.

Helen Dorey is Deputy Director and Inspectress of Sir John Soane’s Museum. For 37 years she has worked on its authentic restoration and published widely on its collections. She has curated exhibitions at the Soane, the RA and Tate Britain and served as a Trustee of the Twentieth Century Society and Moggerhanger House Preservation Trust. She is a member of the Councils of the Attingham Trust and the Society of Architectural Historians, of the Collections and Interpretation Panel of the National Trust, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. She was appointed MBE in 2017 for services to heritage.

Free public tours of the restored drawing office take place on Thursdays and Saturdays at 2.30 pm, lasting about 20 minutes, for six people only on a first-come first-served basis on the day (no advance booking). For more information see www.soane.org/visit

The Drawing Office, Sir John Soane Museum received the 2023 Georgian Group Architecture Award for the Best Restoration of a Georgian Interior.

The article is included in the second issue of DMJournal, Drawing Instruments: Instrumental Drawings.