DMJ – The Field of Mars: The Mother of All Conspiracies

30 days hath September.

All the rest, I can’t remember.

— Trad.

To what extent can an object tell a story? The idea that things, particularly things of stone, might speak – or at least induce speech – is innate to our practice of raising memorials and preserving monuments. But understanding what they might be mumbling in voices that have been softened over the centuries can be difficult. This is especially the case when the story is encoded in the first place. Conspiracies and conspiracy theories shape entire political eras: our own, for example, and also the terrifying final decades of the Roman Republic, when the word conspiracy, or conspiratio, was first used with all its modern connotations by Cicero, whose discovery of Catiline’s plot against the Republic marked the beginning of a spiral into civil war. Conspiracies were also a central feature of Italian life in the 19th century – in particular, in that period known as the Restoration after the abdication of Napoleon, so many of the dead horses of the ancien régime were whipped back into life. When public life is characterised by political speech that few believe but no one dares denounce, monuments change; they gain a salience, even a charge, quite unlike that of the mere street furniture that they resemble in more placid times. This is the story of such a protagonist, hiding, or rather standing, in plain sight, in the middle of a city square.

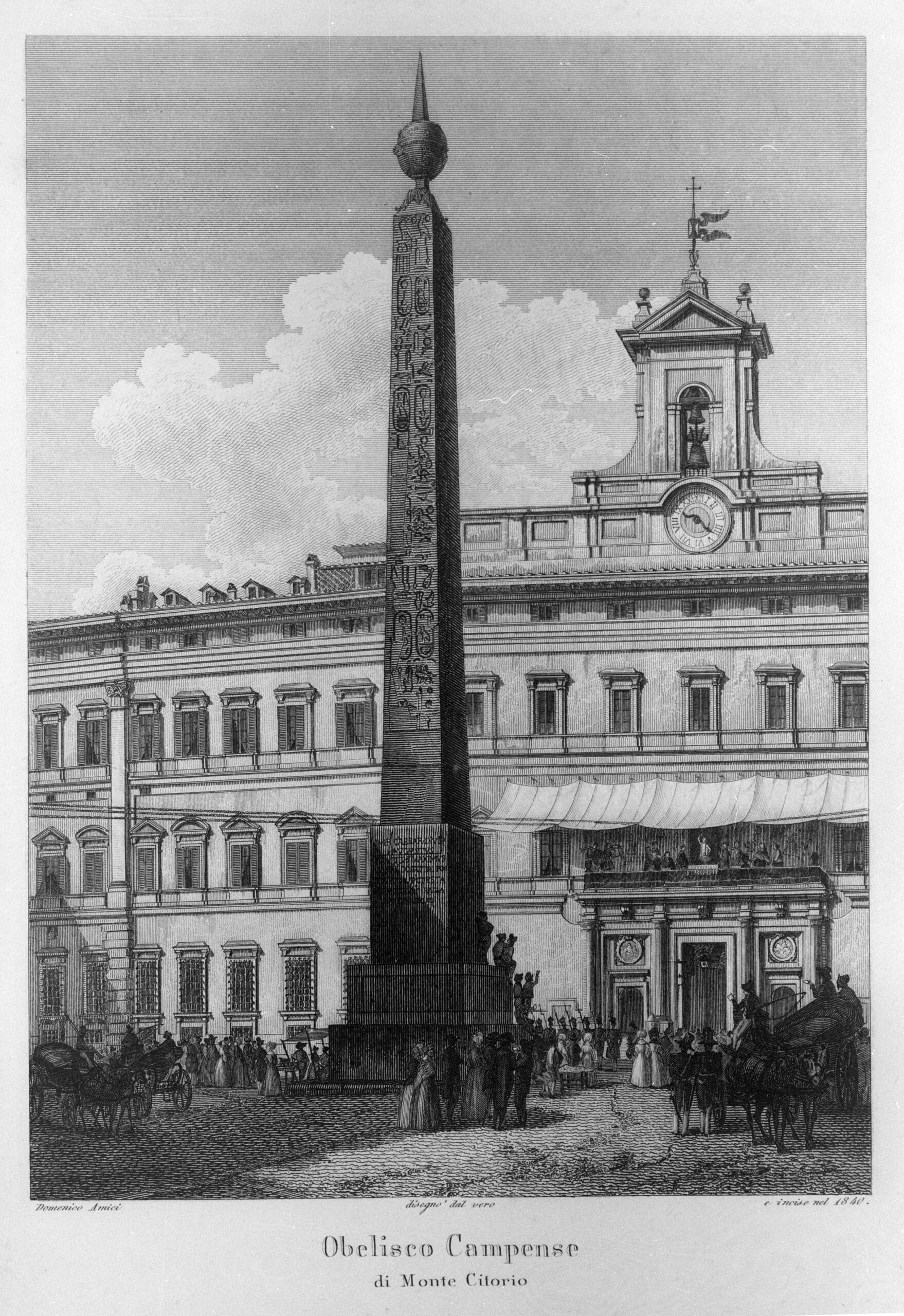

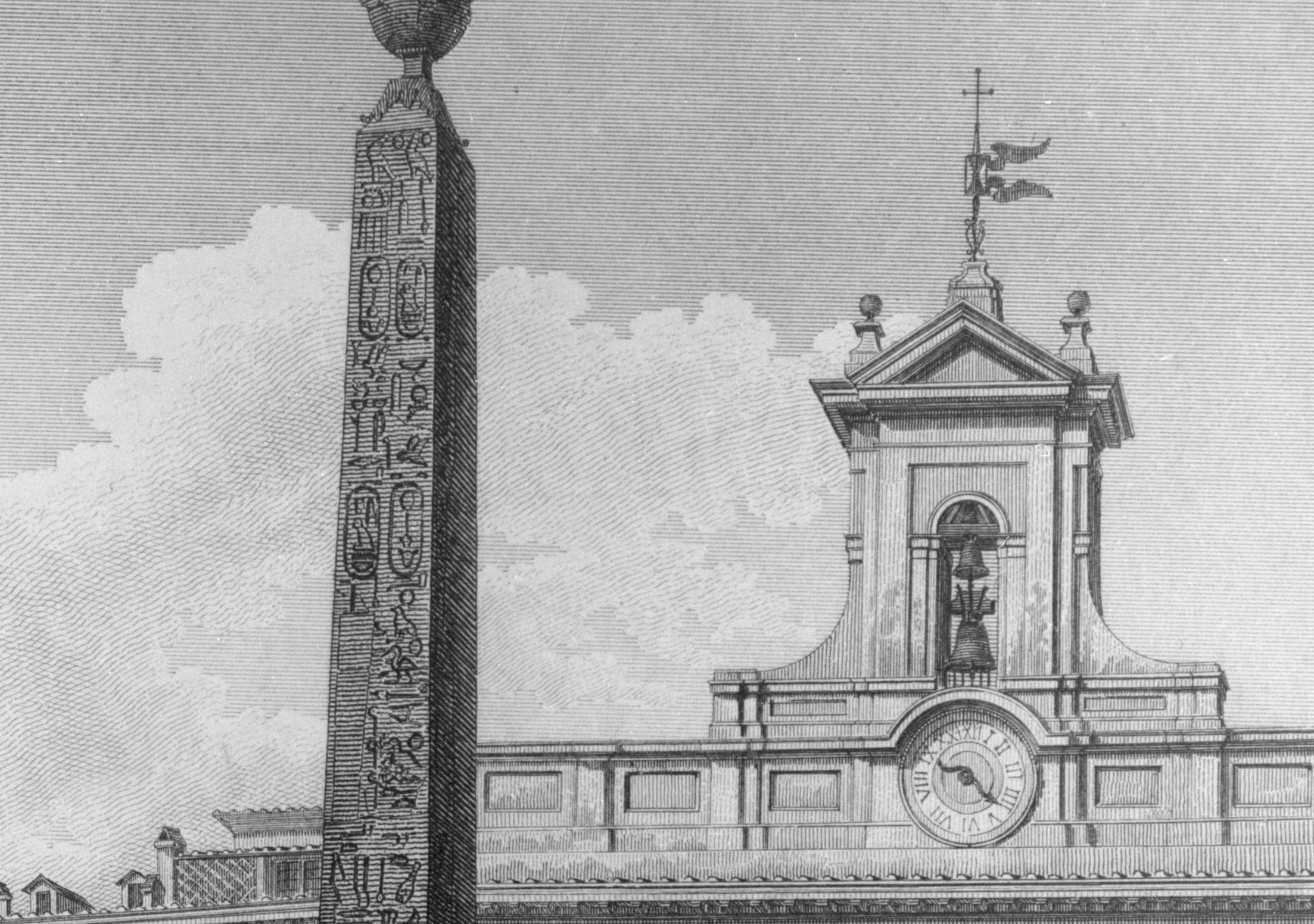

Our first image is a veduta by the 19th-century engraver Domenico Amici (1808–1858), made in 1840 (Fig.1). A tertiary-wave emulator of Piranesi, Amici made prints that were designed to sell, souvenir views of Rome in affordable quarto format editions. The bulk of his life was spent between the artificial re-animation of the Papal States after the abdication of Napoleon, and their dissolution in the nationalist revolution that culminated in the fall of Rome in 1870. Much like the period in which he lived, Amici’s etchings are characterised by both reactionary politics and an atmosphere of unease. His subjects consist of the typical monuments of Rome, and in particular obelisks, their paganism softened by crucifixes and papal banners.

This particular print displays a piazza according to conventions that had been established over the previous 50 years, with the obelisk in the foreground and the Montecitorio Palace in the background. An event is taking place. There is a squadron of soldiers with their backs to us, and a small figure on the balcony, dressed in white. The Montecitorio Palace itself was already a grande dame: it was built in part by Bernini in 1653, with the belfry added by Carlo Fontana in a style that looks better suited to Naples than to Rome. In 1840, the building housed a multitude of important offices for the administration of the Papal States, including the Curia Apostolica and the government of the city of Rome. We may therefore be looking at a major diplomatic event – or just the announcement of the lottery result.

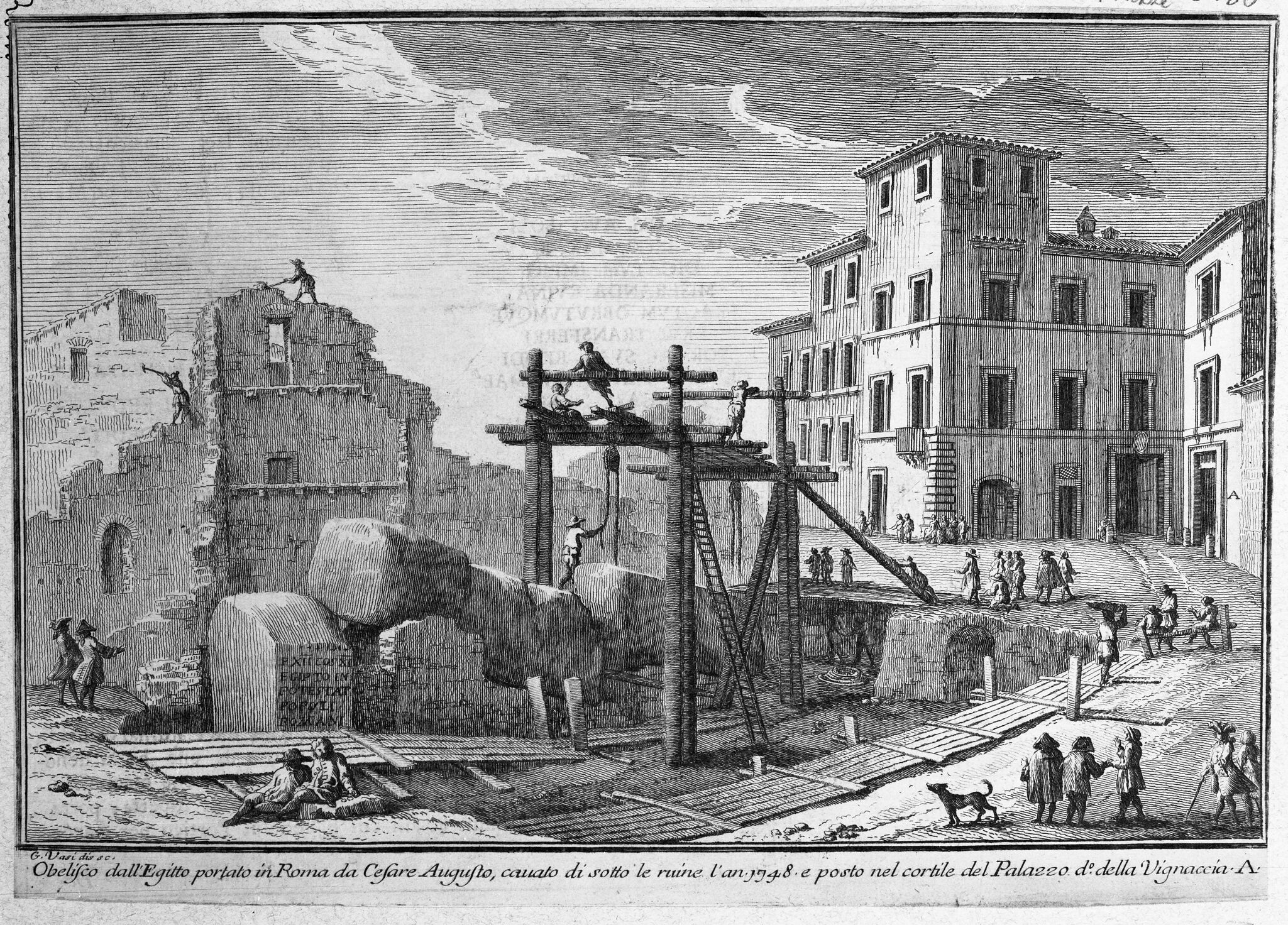

The obelisk in the foreground is older, much older, than the Palace, and is known by many titles that refer to its various past lives: the Obelisk of Psametik II, the Horologium Augusti, the Obelisco Campense, and the Montecitorio Obelisk (which we will mostly use), to name only some. It is recorded as a single mark, number 344, somewhat to the north of the Palace, on the Nolli plan (1748). Throughout the 18th century, the Montecitorio Obelisk was subject to a stop-start excavation that culminated in its eventual resurrection in 1792. Two moments in that process are recorded in popular etchings of the time. One is a folio-sized image by Giuseppe Vasi (Fig.2), which shows the fallen obelisk as heavy, recumbent, almost somnolent. In his 1738 Obelisco cavato di sotto le ruine, Vasi is remembered as the teacher of Piranesi and it is easy to read their shared reverence for the vanished city in the broken obelisk.

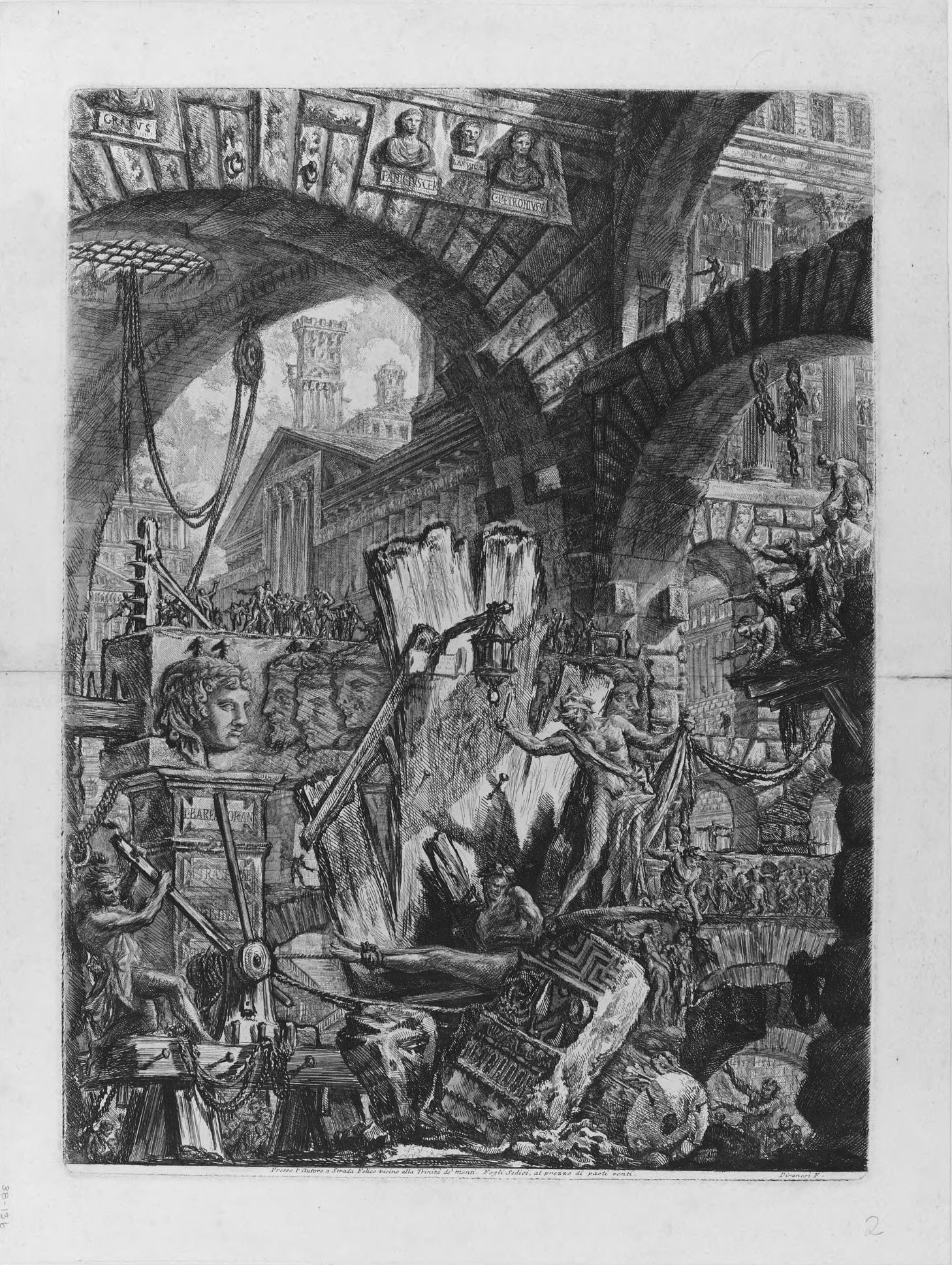

Another similarly sized image, by the French painter Jean Barbault, and possibly printed in Vasi’s workshop a decade later, emphasises the large wooden sheerlegs set aside the stones, the block and tackle, the teams of men operating capstans (Fig.3). Barbault’s image grants the excavation the drama of a distant sea voyage, up to the image of engineer Nicola Abaglia, marked with the letter ‘R’, standing upon the central stone like a captain on deck, although the obelisk itself will continue to lie prone for decades to come. Between all the images is a gap of almost a hundred years.

The memory of the Roman obelisks was potent enough that many of them would be excavated and re-erected during the Baroque period by the most powerful members of the college of cardinals as markers of Rome’s renewal. The Obelisco Campense had first reached Rome in the middle of the reign of the Emperor Augustus. It was set in the centre of the Campus Martius, known to English speakers as the Field of Mars, the parade ground outside Rome where, in the first centuries of the Republic, in that annual demonstration of military psychosis, the legions would be mustered to begin their campaigns of assimilation or extermination against their neighbours. The Obelisco Campense, Augustus’ obelisk, was one of two that he raised in that same year. The other, the Flaminio Obelisk, was set in the Circus Maximus. This pair would be followed by a dozen more, erected over the course of the Empire. The Vatican obelisk in St Peter’s Square was, for its part, even more famous than the Campense, for it was the only one not to fall during the long Middle Ages. Some believed that it had witnessed the martyrdom of St Peter, and others that Caligula had the ashes of Julius Caesar disinterred and deposited in the bronze sphere at its tip during his reign, and that their presence had prevented the obelisk’s collapse for centuries. Pope Sixtus V, in an attempt to repurpose the superstitions around the obelisk to pious ends, had Caligula’s obelisk transported and re-erected in the Vatican square (as carefully described by the architect of its transport, Domenico Fontana), and replaced the bronze sphere with a crucifix.[1]

Our obelisk, this obelisk with its many names, had once stood in the city of Heliopolis, dedicated to Ra, around the sixth century BCE. It was toppled, perhaps less than a century later, by the invading Persians and had lain in ruin before being brought to Rome. Its meaning, on arrival, was therefore already complex. One signification that it bore was that of military victory. Augustus had triumphed over Mark Antony, a fellow triumvir and favourite of his great-uncle, Julius Caesar, at the battle of Actium in 31 BCE. The victory ended a series of civil wars that had threatened to dismember the Roman State. It was therefore fitting to erect an exceptional monument, one exceeding the scope of a triumphal arch – a monument that showed Rome’s pre-eminence, even beyond the Italian peninsula. The obelisk was sacred to the Egyptian sun god and for the syncretic Romans the transportation to and resurrection of the obelisk on Roman soil was a clear symbol of the new tributary relationship of Egypt to Rome. Moreover, given the popularity of the Egyptian mystery cults in Rome, it may be that the translocation of the obelisk was understood by cult adherents as an affirmation by the Egyptian gods of Roman cosmopolitan rule. As well as being a monument to victory, it was also intended as a monument to the ensuing peace. Bounding the site to the north-west was the Ara Pacis, the temple of peace established at Augustus’ behest in 13 BCE, with its images of thanksgiving, abundance and conviviality. Augustus’ emphasis on the fruits of victory accelerated the slow shift of the site from military use to civic celebration.

But interpretations of the monolith did not stop here. Another begins by tracing the path of its shadow. As Pliny the Elder remarked in his Natural History:

The obelisk in the Campus was put to use in a remarkable way by the deified Augustus so as to mark the sun’s shadow and thereby the lengths of days and nights. A pavement was laid down for a distance appropriate to the height of the obelisk so that the shadow cast at noon on the shortest day of the year might exactly coincide with it. Bronze rods let into the pavement were meant to measure the shadow day by day as it gradually became shorter and then lengthened again.[2]

That is to say, the obelisk worked as a giant sundial. Each day, at midday, when its shadow was shortest, its tip would meet a bronze line inlaid in the paving stones. The archaeologist Edmund Buchner argued that the tip of the shadow would stretch towards the doorway of the Ara Pacis on Augustus’ birthday, creating a visual bridge between the festive events and the temple of peace that the Emperor had consecrated.[3]

Much historical debate around the obelisk – starting with Jean Hardouin’s annotated edition of Pliny’s Natural History in 1685, kept alive by Angelo Maria Bandini’s 1750 publication De obelisco Caesaris Augusti, and culminating in Buchner’s physical excavations and commentary of 1980 – has turned on the question of whether or not the paving stones of the Campus Martius indicated every hour of the day or showed a meridian line only where the shadow fell at midday. This debate, upon which antiquarians and archaeologists staked their careers, could only matter if the obelisk was being used to indicate exact time, but a clock the size of the Campus Martius could hardly be read precisely.

We cannot criticise archaeologists for the minute reading of old stones and the shadows that they cast. But for us, the question is: why make a clock whose presence could be seen from one side of the city to the other? Explaining this requires another rotation around the thing. Note the meaning of obelisks attested in ancient Egyptian literature and Pliny’s writings – namely, petrified sunbeams. Cut from the hardest possible stone with tools of copper and wood and water, the labour of hundreds of human lives, they were erected as petrified rays from the god Ra. Usually engraved with hieratic inscriptions, the Egyptian obelisk manifested the coincidence of secular and divine power. On such an object, erected with exorbitant force, inscriptions did not only read as representations, let alone as a public service announcement, or any of the other secular categories of semiotics with which we roll through contemporary times, but rather as a transcript of the will of heaven.[4] Literate Romans would have known something of the religious meaning of the obelisks, but the new meaning it acquired in the Field of Mars would have been still more potent, for reasons attached to political events that were very much in living memory. This memory formed the living context of the monument and encompassed not only the civil war, but also the symbolic dislocation and the famous assassination that preceded it. The great stone finger didn’t explicitly refer to the chaos, insecurity and mayhem that preceded its elevation, but it pointed to their cause.

Before the edicts of Julius Caesar, Rome observed both a lunar and a solar calendar. The number of days in each month was not fixed, but was instead based on the priest’s observations of the phases of the moon. Even in the late Roman Republic, the determination of the dates of a month, the exact timing of the Ides and the Nones, was a religious ritual that was a prerogative of one of the Plebeian priests of the city. Furthermore, as there is an 11-day difference between the length of a lunar and a solar year, continual ad hoc adjustments to the calendar were necessary to maintain the clear relationships of the seasons. So once every few years, the priests would insert a new month called Mercedonius, a ‘workaround’ month that would straighten things out – or not.

Plutarch, in his account in the Lives, tells the story well.

For not only in very ancient times was the relation of the lunar to the solar year in great confusion among the Romans, so that the sacrificial feasts and festivals, diverging gradually, at last fell in opposite seasons of the year, but also at this time [during the late Roman Republic] people generally had no way of computing the actual solar year; the priests alone knew the proper time, and would suddenly and to everybody’s surprise insert the intercalary month called Mercedonius. Numa the king is said to have been the first to intercalate this month, thus devising a slight and short-lived remedy for the error in regard to the sidereal and solar cycles, as I have told in his Life. But Caesar laid the problem before the best philosophers and mathematicians, and out of the methods of correction which were already at hand compounded one of his own which was more accurate than any. This the Romans use down to the present time and are thought to be less in error than other peoples as regards the inequality between the lunar and solar years. However, even this furnished occasion for blame to those who envied Caesar and disliked his power. At any rate, Cicero the orator, we are told, when someone remarked that Lyra would rise on the morrow, said: ‘Yes, by decree’, implying that men were compelled to accept even this dispensation.[5]

Following the precedent of Numa, the founding king, the priests inserted months – or refused to insert months – thereby extending or reducing the length of political appointments. In addition to the insertion of an entire month, Mercedonius, the priests’ observations determined when the new moon had appeared. If they chose to, they could bring the date forward or delay it. Plutarch’s dry humour makes the confusion sound more innocent than it was. Their right to control the dates could be used like a filibuster, as the Senate of the city of Rome sat on predetermined feast days.[6] It was therefore a potent source of secular political power, and was used as such.

Caesar, in his role as pontifex maximus, not only made use of this power himself but, recognising its disruptive capacity, dared to extinguish many centuries of ritual by introducing a new solar calendar all his own. He thereby replaced a system of negotiation with a rigid standard. By decoupling the month from the moon he, however, also introduced his own, irrevocable drift between the apparent date and the cycles of nature. The constellation of Lyra, whose rising marked a key festival of the solar year, now rose on the wrong day. Cicero’s acerbic ‘Yes, by decree’ was a reference to Caesar having overstepped the boundaries of secular power, presuming to command the stars. Caesar had not only degraded the priests to cripple his enemies in the Senate, but had also set in train a strange parallelism in the highest levels of society, fostering a clique within Rome who in all regards wished to restore the old order, the clique known as the optimates, those fetishists of the mos maiorum, the ‘custom of the ancestors’. The change to the calendar is the first episode in Plutarch’s narrative, which culminates in Caesar’s assassination.

In all our received accounts – from Plutarch and Suetonius to Shakespeare and all the story-tellers who fall between them – of that mother of all conspiracies, the assassination of Julius Caesar, there is the curious role of a seer who warns Caesar ‘Beware the Ides of March’. In Shakespeare, we are in the logic of theatre – the audience already knows that the sovereign is going to end up a pin-cushion for the senators’ knives, and enjoys seeing him needled beforehand. In Plutarch, writing around 150 years after the event, we are in the realm of historical narrative – not truth, exactly, but a making-sense of history. In the classic 1919 Loeb rendition, when Caesar encounters the seer, whose name was Spurinna, ‘he jeered at him and said, “Well, the Ides of March have come”, and the seer said to him softly, “Aye, Caesar, but not gone.’”[7] The seer responds softly – whether the words are said complacently, or mournfully, is up to the actor.

‘Beware the Ides of March’ is not so much a prediction as a threat with a double edge. On the one side, the seer knows a conspiracy is brewing. On the other, he is insinuating something else: Caesar, having taken it upon himself to meddle with time, shouldn’t be so confident about when the Ides are finished with him. The ‘Ides of March’ is not only a reference to the date of Caesar’s assassination, but also an allusion to its cause. How much is condensed in the phrase ‘Beware the Ides of March’. March was a month of spring dedicated to the god Mars, when men of fighting age paraded in the Campus Martius. The Ides were the day on which a sheep was always sacrificed to Jupiter; a day on which debts fell due, one in which acts of revenge could be cast as the payment or fulfilment of a debt. And Caesar, in his hubris, having rearranged the months and having demoted the priests who scanned the sky for the new moon, was in no position to know when the gods, the Dii Consentes, might think his number was up, even if they told him.

The schoolbook account of Caesar’s fall – that he had treated the Senate with contempt, dismissed tribunes, and threatened to set himself up as a monarch – tells the story in terms of liberty and power that resonate easily for modern readers. But we can defamiliarise it and ask not whether Caesar abused his power but, rather, what makes power legitimate, what are the ways that power calls upon nature to ratify its authority? This reversal of the terms foregrounds the necessity of secular power to appear as if in agreement with the natural order of things. After a period of chaos, of transient rulers, betrayals and massacres, how does power renaturalise itself? Sacred ritual is indispensable in producing this agreement, or, better, making it look consilient, but once the stars are out of alignment, it is difficult to jam them back into place.

This leads us back to the problem facing the Emperor Augustus. From 45 BC to 9 BC, the Julian calendar was badly implemented, and too many leap years had been inserted. Augustus suspended leap years in 8BCE, until the astronomical solar year and the calendar were resynchronised. Augustus’ agenda is therefore absolutely clear. As the heir to the (now) deified Caesar, he perfects the Julian calendar. The giant obelisk, dedicated to the sun, casts its shadow as it should upon the paving stones, showing the perfect accord between natural and secular power, and offering daily heavenly affirmation of a new covenant. The monument can be understood as a dynamic broadcasting tower declaring the identity and indivisibility of sacred, secular and natural power, all of it vested in the Emperor.

Of course, nothing stays perfect. Where heaven could be brought to agree, the earth provided resistance. Over time the obelisk became inaccurate. As Pliny noted in a passage following the one quoted above:

The readings thus given have for about 30 years past failed to correspond to the calendar, either because the course of the sun itself is anomalous and has been altered by some change in the behaviour of the heavens or because the whole earth has shifted slightly from its central position, a phenomenon which, I hear, has been detected also in other places. Or else earth-tremors in the city may have brought about a purely local displacement of the shaft or floods from the Tiber may have caused the mass to settle, even though the foundations are said to have been sunk to a depth equal to the height of the load they have to carry.[8]

Decades later, Domitian would re-lay the stones of the Campus Martius in an attempt to recalibrate the shadow’s path.

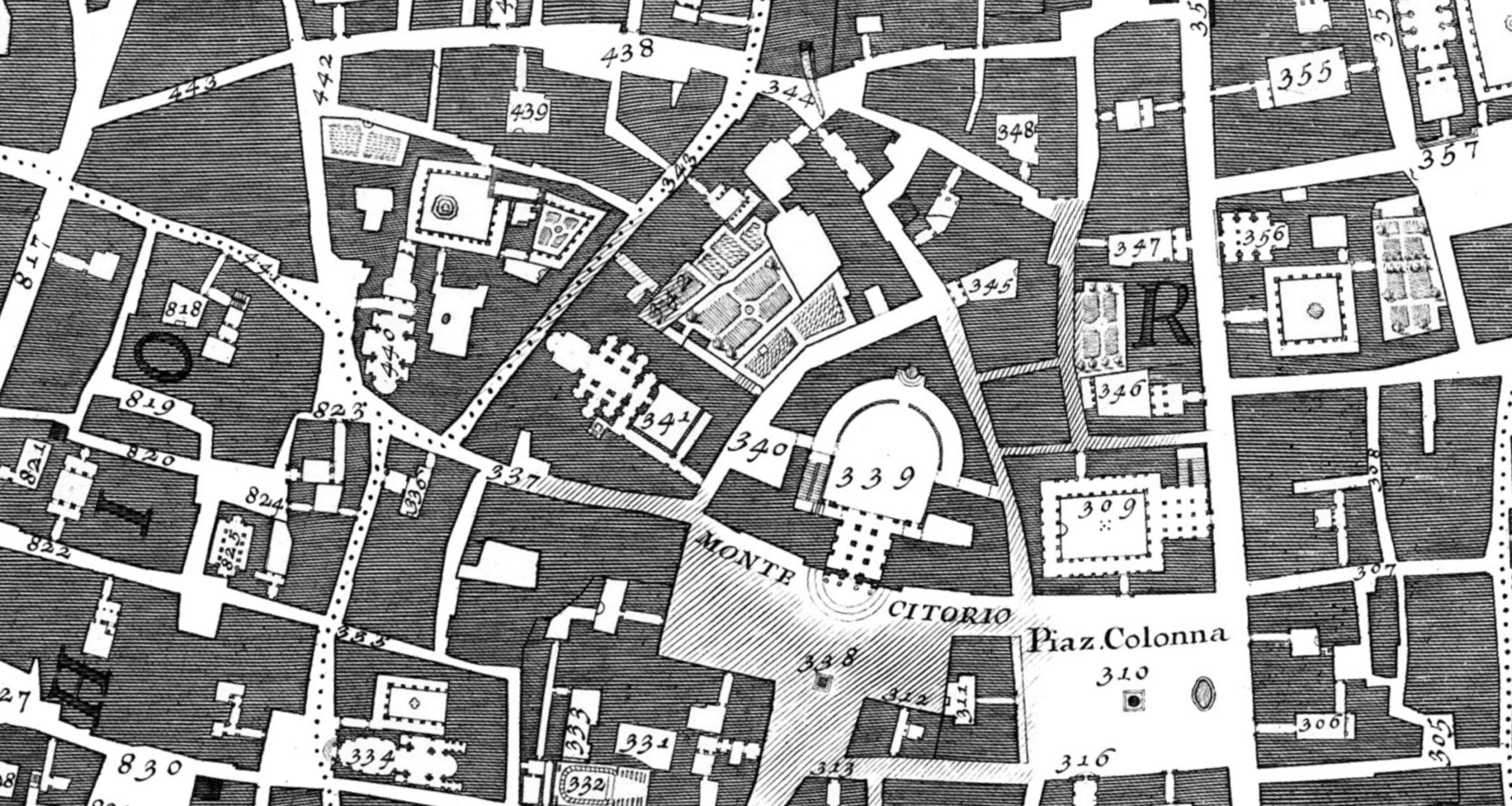

Both the Campus Martius and Time had become personified gods by this point, just as Caesar and Augustus had in the meantime also become gods (Fig. 4).[9] Gods, gods, everywhere, to be propitiated and beseeched and manipulated and called upon, woven into human narratives and human ends. But no matter how forcefully an ideology may assert it, nature does not serve power – inexhaustible resistance might be one definition of what nature is. The obelisk fell some time in the ninth century, it is believed. Rome was, in any case, already enough of a ruin that there was no Pliny to record the event. Is it any wonder that the broken obelisk of Vasi’s engraving is, in formal terms, closer to Piranesi’s body being broken on a rack than to the polite symmetry of Amici’s restored pointer (Fig. 5)? Nolli had captioned mark 344 on his map with the dry remark, ‘Palaz. Conti con Obelisco Solare giacente’: the Italian giacente means ‘lying there’, but it can also mean ‘dead’ or ‘unclaimed’ (Fig. 6).[10]

Goethe would visit it in 1787, a few years before its restoration, and wrote of its paradoxical condition.

The mighty obelisk, raised by Augustus on the Campus Martius to serve as a sundial, was now lying in fragments, enclosed by a wooden paling in a filthy corner awaiting the bold architect who might be called to set it up again. It is hewn out of genuine Egyptian granite and thickly besprinkled with neat naive figures, though in the well-known style. Standing, as we did, beside its pinnacle, formerly piercing the higher strata of air, we thought it remarkable to see on the tapering slopes the prettiest images of sphinx after sphinx, a sight in earlier times allowed to no human eye, but only to the beams of the sun.[11]

Perhaps Amici’s engraving was not so generic as it at first seems. Citizens of the tiny Papal States, frozen in time, reactionary, and increasingly paranoid, were within Amici’s own lifetime aware that their temporal power was coming to an end. In November 1848, Pellegrino Rossi, the minister for justice of the Papal government, would be assassinated in Rome, triggering the flight of Pope Pius IX, disguised as an ordinary priest. Hidden within Amici’s carefully made illustration, one sees the parallelism of the bell tower of the Montecitorio Palace and the tip of the obelisk. At the base of the crucifix on the bell tower is a weathervane in the form of an hourglass with wings: tempus fugit – time flies. Both these monumental devices of time measurement dwarf the diminutive figure of the man on the balcony. The pointer on the clock is not even hands, but a serpent, wrapping its body around the unseen axis of rotation (Fig. 7).[12]

Notes

- See, for example, André Tavares, ‘The Anatomy of the Architectural Book: Magical Moves’: https://drawingmatter.org/the-anatomy-of-the-architectural-book-magical-moves/ [accessed 10.01.25].

- Pliny, Natural History, Volume X: Books 36–37, trans. D.E. Eichholz (Loeb Classical Library 419, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 260–63. Also cited in Buchner (1980), 355–57 (see below).

- Although this is not a hypothesis that is universally accepted. Edmund Buchner, ‘Horologium Solarium Augusti: Vorbericht über die Ausgrabungen 1979/80’, Römische Mitteilungen 87 (1980), 355–73.

- As understood by the unhappy judge Daniel Paul Schreber, who at the height of his paranoid psychosis realised that divine speech shot across the sky in the form of sunbeams. Schreber, Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, trans. and ed. Ida Macalpine and Richard A. Hunter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1955), 55–60.

- Plutarch, in Lives, Volume VII: Demosthenes and Cicero. Alexander and Caesar, trans. Bernadotte Perrin (Loeb Classical Library 99, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919), Caesar 63, 594–97.

- See the passage 40.60–40.62 of Dio Cassius, Roman History, Vol. IV, Books 37–40, trans. Ernest Cary (Loeb Classical Library 53. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1925), 362–69.

- In Plutarch, the seer is a haruspex, a specialist in examining organs after sacrifices; in Shakespeare, a soothsayer. Plutarch, Lives, op. cit., Caesar 63, 556–61. Compare to William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene 2.

- Pliny, op. cit., 263–64.

- All of them are figured on the wonderful relief known as the Apotheosis of Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina. The relief was part of the pedestal of a memorial column to the dead emperor. The male figure, holding our obelisk like a phallus, is the embodiment of the divine Campus Martius. The winged god is Aion, god of time, who is delivering Antoninus Pius and Faustina up for deification.

- See the legend accompanying the Nolli Map, or, more exactly, the index of the map numbers. Giovanni Battista Nolli, Nuova Pianta di Roma (Rome, 1748), ‘Indice dei numeri della pianta’, 11.

- Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Italian Journey, trans. Charles Nisbet (London: Penguin Books, 1970), 270.

- I owe this (and not only this!) sharp-eyed observation to Mark Dorrian.

Adam Jasper is an Assistant Professor at the School of Architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). He studied philosophy and art history in Sydney, Melbourne, and Freiburg (Breisgau). From 2010 to 2014, he was a lecturer in the Faculty of Design, Architecture, and Construction at the University of Technology Sydney. During that time, he was editor of the Architectural Theory Review (Taylor and Francis), and a contributing editor for Cabinet Magazine, as well as a regular contributor to Artforum. From 2018 to 2024, he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (GTA), where he served as the editor of GTA Papers magazine.

*

The article is included in the third issue of DMJournal, Storytelling.