The ‘indispensable ingredients of sublimity’: Smirke and Papworth’s Designs for the Wellington Testimonial

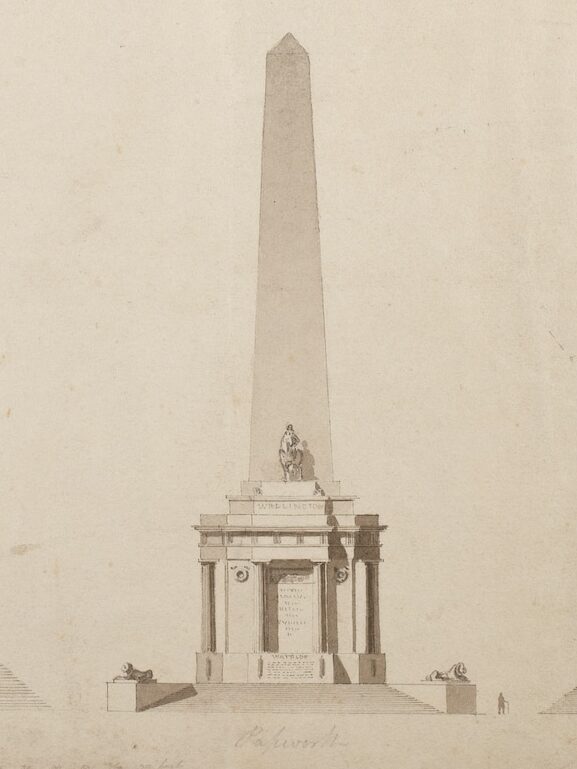

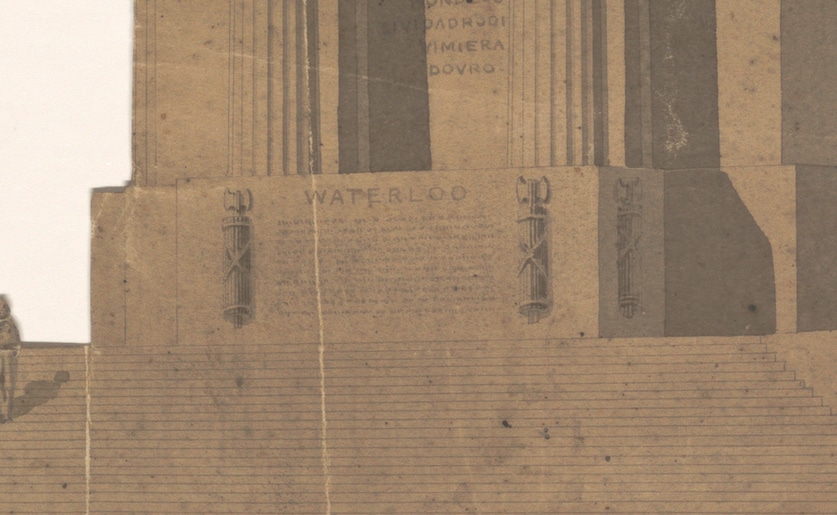

In 2001, the Irish Architectural Archive (IAA) acquired at auction an item described in the catalogue as ‘Architectural Drawing, possibly by Robert Smirke, of Wellington Monument, Phoenix Park’. The unsigned, undated drawing is a perspective view of an obelisk, the base of which is a four-faced distyle Doric temple. This stands on a tall plinth which sits on a stepped platform at the corners of which are recumbent lions on pedestals. Between the free-standing columns of one face of the temple is a list of battles, running chronologically from ‘Douro’ to ‘Pampeluna’, while the plinth bears a longer (illegible) inscription framed by fasci and set beneath the word ‘Waterloo’. Unusually, the drawing is carefully cut from its original sheet of paper along the edges of the structure.

The list of battles, the prominence of the word Waterloo and the obelisk form all suggest the Dublin Wellington Testimonial—Wellington was alive when it was erected, hence Testimonial as opposed to Memorial or Monument—so could this be an alternative scheme by Smirke to his actually executed trophy? And if so, could recently discovered sketches by Smirke now in the Drawing Matter collection assist in furthering the attribution?

On 20 July 1813 a meeting of ‘Noblemen and Gentlemen’ took place in the Rotunda, Dublin, to consider a tribute to the Irish-born Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, which would suitably convey ‘a nation’s admiration of the transcendent exploits of her son and hero’.[1] The meeting resolved on the erection of a monument and a committee of seventy-four ‘managers’ was appointed to progress the project. This was soon increased to eighty-five, thirty-five of whom were Peers. The committee established a fund, subscription to which quickly reached £16,000 of the estimated £20,000 required, and issued a call for the submission of suitable designs. By July 1814, the committee could report that a large number of these had been received from various parts of the United Kingdom.

There was a range of opinions amongst the managers as to what would constitute the most suitable design, but in general they leaned towards classical forms—arches, temples and columns. On one consideration they did agree; as one of the managers put it, ‘Height and Extension will ever be found by the Architect indispensable ingredients of sublimity’.[2] More colloquially, the monument should be the biggest and most obvious to be had for the money available.

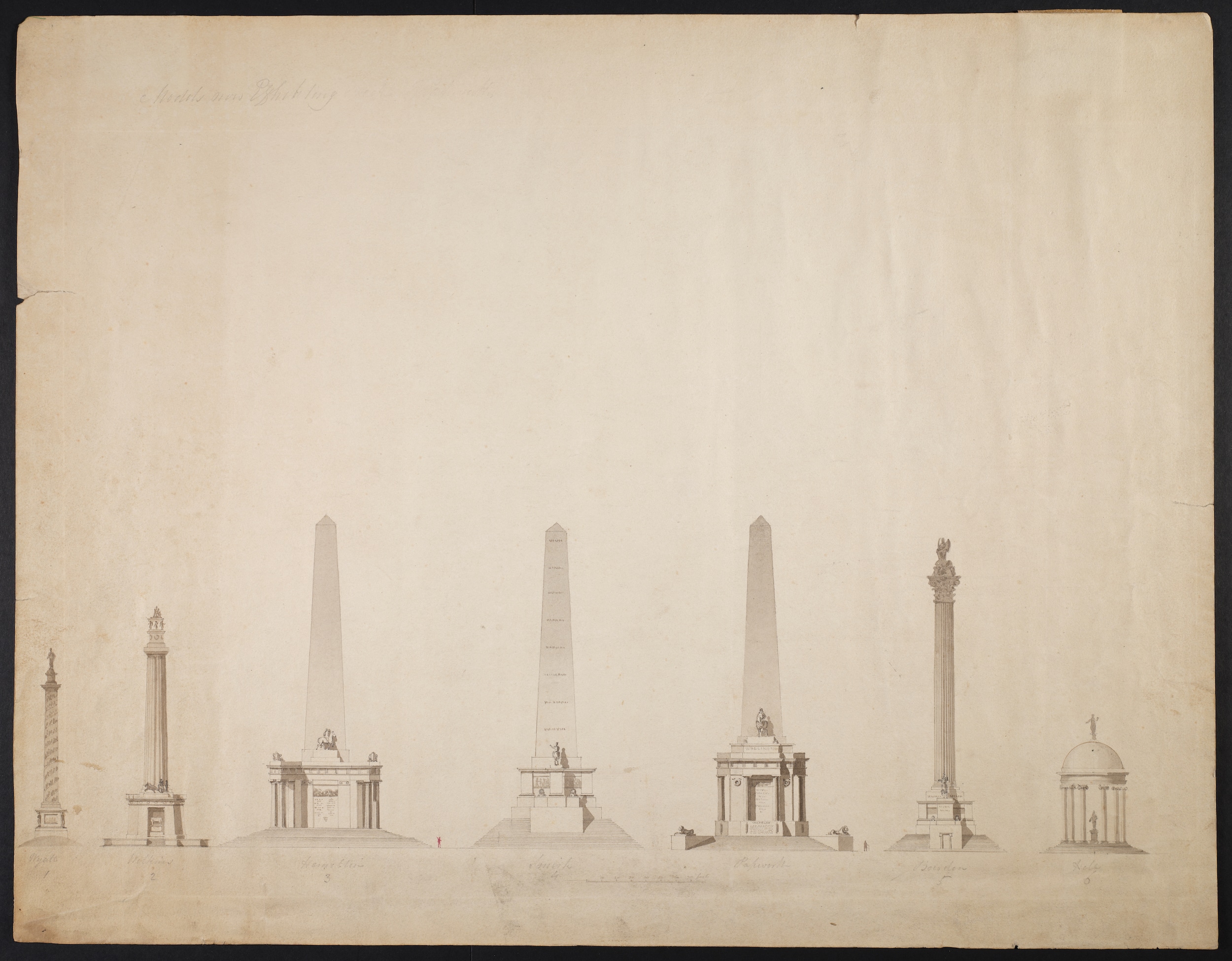

Six designs were awarded premiums, one temple, three columns, and two obelisks, including one by Robert Smirke. A composite drawing of elevations of these six was published, and models of each were made for public display in late 1814. The exhibition of models proved decisive. One of the managers, John Leslie Foster, reminded John Wilson Croker, a friend of Wellington’s, that they had both publicly come out against an obelisk but

‘it happened that we saw the exhibition together for the first time, and you remember the mutual acknowledgement of our common error… we became practically persuaded of what we had not been aware, that the Obelisk… was susceptible to beauty of the highest order, entirely unknown to the Obelisks of antiquity, and that they further possessed this important recommendation, that any given sum of money expended on the construction of either, would excite the impression of majesty, grandeur and durability, more extensively than could the same sum laid on in the erection of a Column’.[3]

An obelisk, the models suggested, would give the bang for the buck required. Smirke’s proposal was selected by the committee as the preferred design on 11 December 1815.

There are drawings for Smirke’s obelisk in the RIBA drawings collection. These show a base of sloping steps 20ft high on which sits a tiered plinth of 37ft, surmounted by an obelisk of 163ft, tapering from 28ft at the base to 14ft just below the pyramidal summit. On the plinth are panels containing sculptural depictions of Wellington’s victories, and on one side are three pedestals, a principal one for an 18ft equestrian statue of Wellington and two subordinates for recumbent lions.

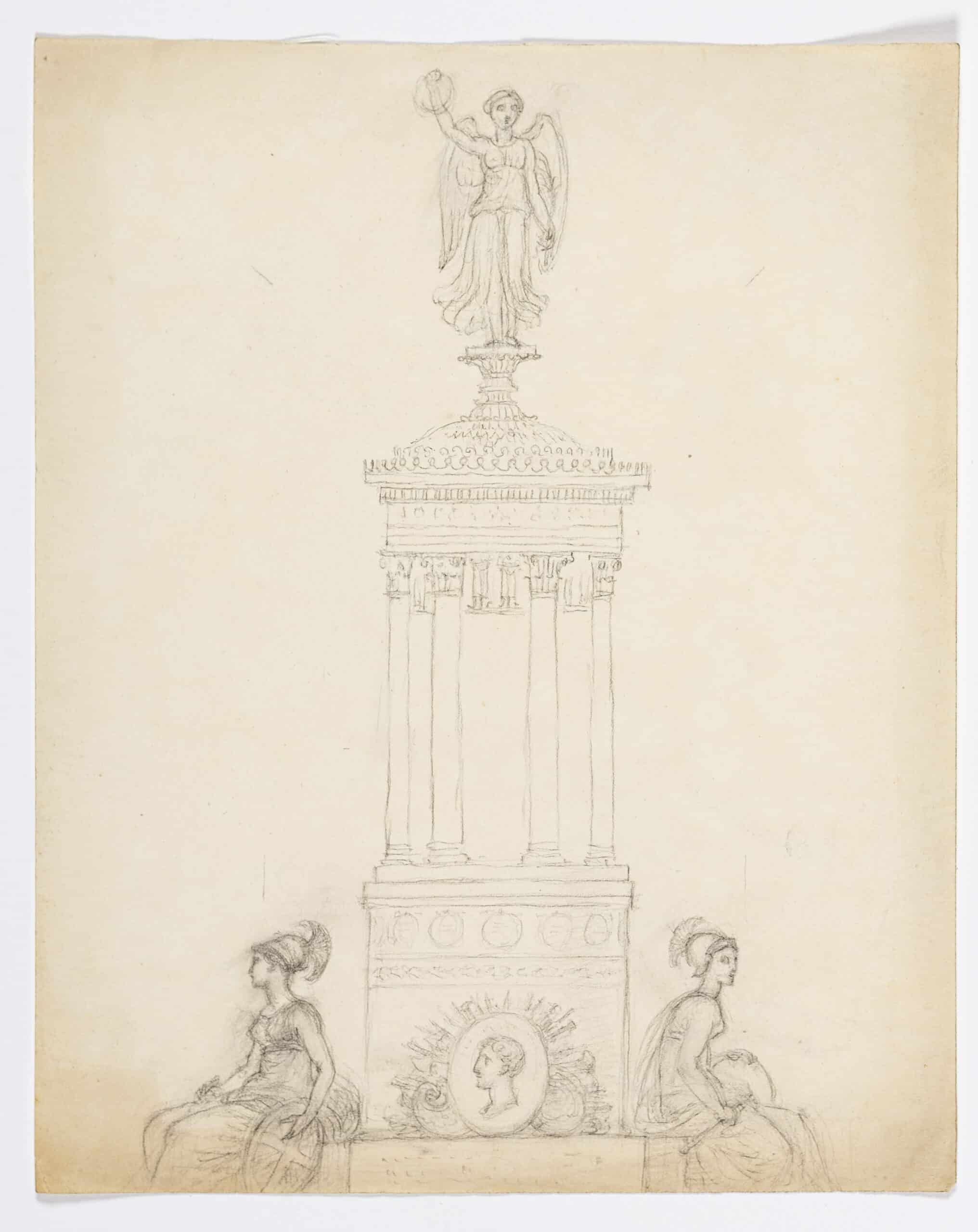

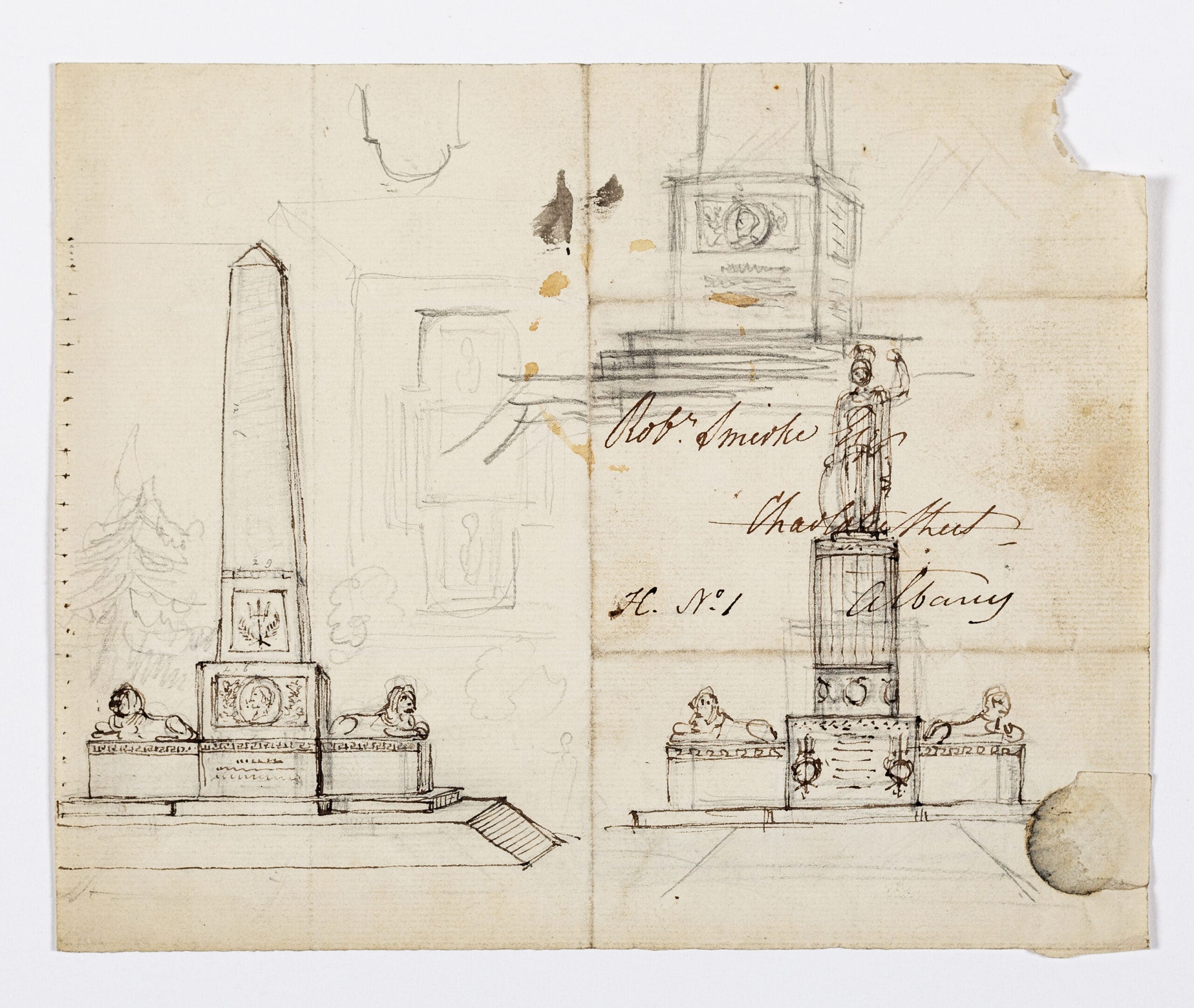

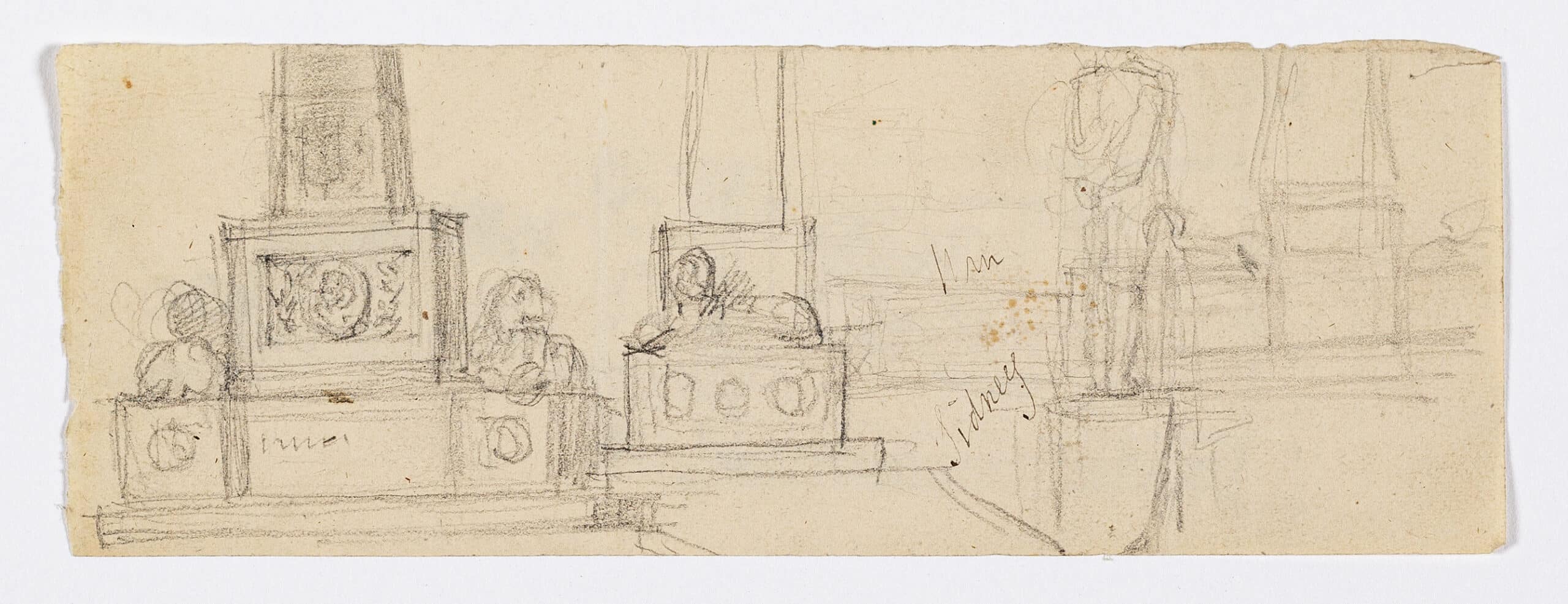

As the sketches now in the Drawing Matter collection show, Smirke had explored a variety of options for the monument before arriving at his submitted proposal. He considered a statue, either Wellington or a personification of Victory, on a drum or polygonal pedestal. He mulled over various forms of a monopteros temple, investigating how it might be elevated on a mound or base and how it might be accompanied by statuary including recumbent lions, Victory or the hero on a horse. (Interestingly, one of the premiated designs was for just such a temple containing a statue of Wellington and surmounted by a second representing Victory. Much to the very public annoyance of its designer, a Dr Edward Hill, this was rejected for being insufficiently grand.)

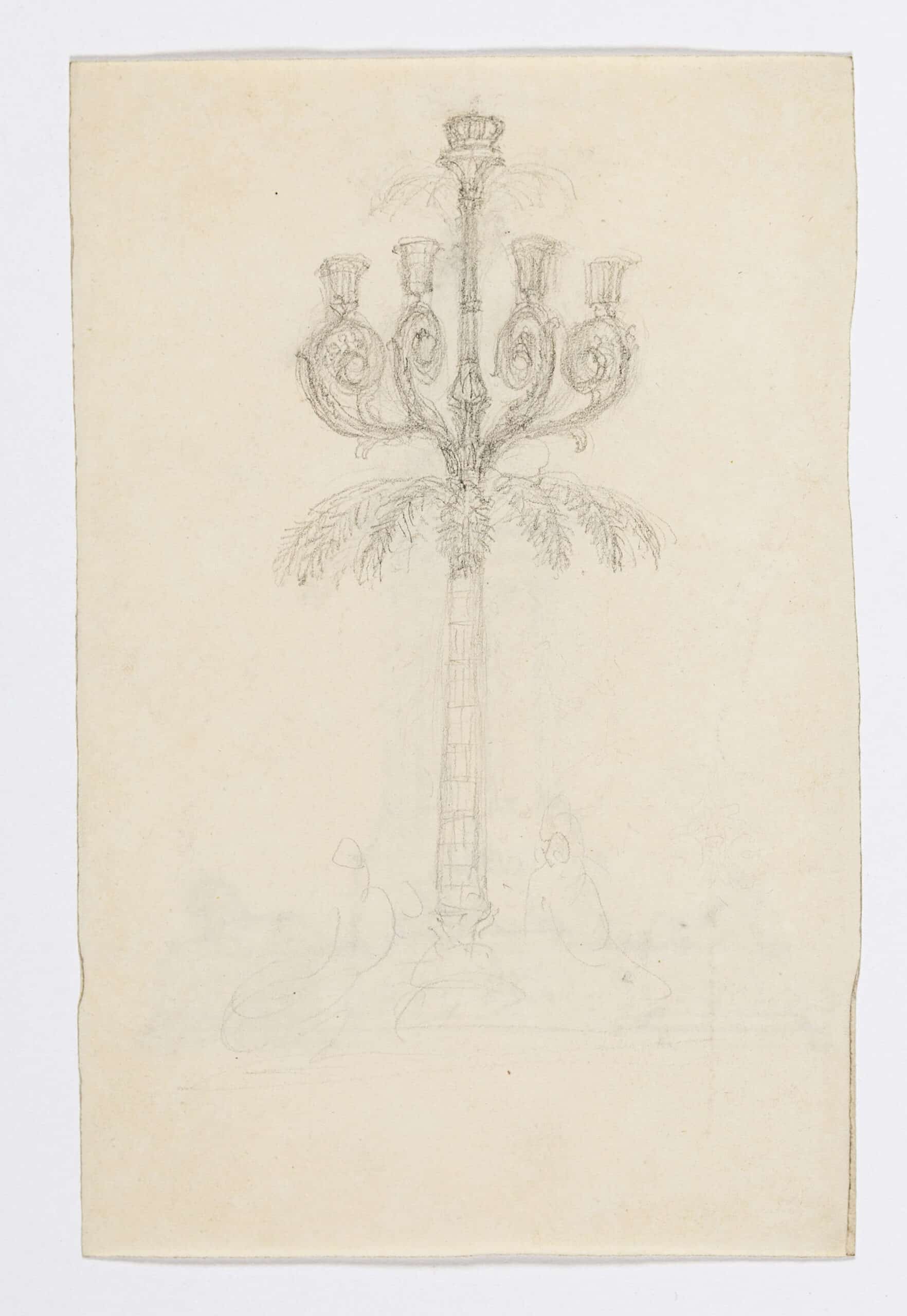

Smirke’s most whimsical idea was for a four-light palm-tree lampstand topped by a crown, while another of the Drawing Matter sketches contains the germ of his winning scheme. This is an actual back-of-the-envelope drawing of an obelisk on a stepped platform flanked by recumbent lions. Beefed up to meet the committee’s required monumentality, and with the lions now accompanied by an equestrian statue, Smirke’s obelisk won the day.

What light can the Drawing Matter sketches shed on the IAA’s drawing? Well, they make it clear that it is not by Smirke. There is no hint of the Doric in any of Smirke’s sketches or final design, nor is it likely that he would have submitted two different obelisk proposals. As noted, a drawing of the premiated designs was published at or about the time the models went on display in late 1814. There is a similar drawing in the National Library of Ireland (NLI) but this one shows seven Wellington Testimonials instead of six. A pencil note on this drawing reads ‘Models now Exhibiting’. Added under six of the seven elevations are the numerals one to six, corresponding to the six exhibited designs, as well as the names of the designers. The fourth elevation from the left is not numbered but there is a name – ‘Papworth’. An obelisk on a Doric temple base on a stepped platform, this scheme corresponds almost exactly to that in the IAA.

From left to right: James Wyatt (1746–1813), William Wilkins (1778–1839), David Hamilton (1768–1843), Sir Robert Smirke (1780-1867), George Papworth (1781–1855), John Bowden (d. 1822) and Dr. Edward Hill (1741–1830).

George Papworth (1781–1855) showed three drawings for the Wellington Testimonial in the Hibernian Society of Artists exhibition in 1814. One of these—a west elevation—was described in the exhibition catalogue as ‘intended to be laid before the Wellington Committee’. The records of the committee were destroyed in a fire in 1825, and so it is impossible now to know if this scheme was actually submitted. Papworth returned to the Hibernian Society of Artists the following year, 1815, with two sketches for the Testimonial and a model which, the catalogue stated, had been ‘exhibited and laid before the Wellington Committee’. The creation of a model was an interesting step; models had, after all, been made of the six premiated schemes and were proving key to the selection of a winning design.[4]

On both the NLI and IAA drawings the word Waterloo is prominent, indicating that they post-date June 1815. They present a version of the scheme in the exhibited sketches and model, updated to reflect recent momentous events and therefore more current than the six designs the managers were considering. The inclusion of this proposal with those six in the NLI drawing reinforces the claim asserted by the making of the model: if this scheme wasn’t awarded a premium, we are being told, it should have been. Papworth’s combination of classical elements with the now-favoured obelisk form—coincidentally (or not) exactly the same height as Smirke’s—certainly pandered to the predilections of the managers and reinforces the impression of someone hoping to circumvent the committee’s short-list and win the commission for himself.

The managers considered at least nine different locations for the monument ranging from the favourite, St Stephen’s Green, to the final off-centre site in the Phoenix Park. This they settled on in the end only because it was provided free of charge. In its original form, Papworth’s perspective now in the IAA may have been site specific, showing the monument in the surroundings of St Stephen’s Green. These could have been removed after the St Stephen’s Green Commissioners refused permission for any obelisk in 1816, leaving the drawing in its cut-out state. It is perhaps more likely that there was never any context on the drawing and that its cut-out form was intended to allow it to be placed against backgrounds showing any and all possible sites.

In 1819, Papworth once again exhibited three designs for the Wellington Testimonial, this time in the Artists of Ireland exhibition. Included was an elevation and a model, possibly a reshowing of the one exhibited in 1815. The third item was listed in the catalogue as ‘a perspective view of a design… submitted to the Wellington Committee’. Could this be the drawing now in the IAA? Of course, any hopes Papworth ever had of winning the commission were long gone. Construction of Smirke’s Wellington Testimonial had begun in 1817 and the basic structure was completed in 1820. By then the money had run out. The obelisk may well be the tallest in Europe, but it is 16ft shorter than Smirke had proposed and there was nothing left to pay for the decorative panels or statues. For years the Testimonial remained unadorned, a state which left it criticised as nothing but a giant mile-stone. The equestrian statue and lions never materialised and their embarrassingly empty pedestals were eventually removed. The bronze sculptural panels and dedicatory inscription, supposedly cast from cannons taken at Waterloo, were finally unveiled, apparently without ceremony, on 18 June 1861.

Colum O’Riordan is the CEO of the Irish Architectural Archive.

See the full sequence of sketches by Robert Smirke now in the Drawing Matter collection by registering for our collection catalogue, here.

Notes

- Faulkner’s Dublin Journal, 20 July 1813. For the history of the evolution of the monument see ‘The WellingtonTestimonial’, P. F. Garnett, Dublin Historical Record, XIII, No.2, June-August 1952, pp. 45–61.

- A Letter on the Fittest Style and Situation for the Wellington Trophy about to be Erected in Dublin, John Leslie Foster, Dublin, 1815, pp. 19.

- A Letter on the Fittest Style and Situation for the Wellington Trophy about to be Erected in Dublin, John Leslie Foster, Dublin, 1815, pp. 5–6.

- Information on the 1814, 1815 and 1819 exhibitions is from Irish Art Loan Exhibitions: Index of Arts, Vol. II, London, 1995, pp. 546–547. See also Papworth’s entry in the Dictionary of Irish Architects.