Drawing as Advocacy

– Stephanie Davidson and Mary Vaccaro

These drawings are the result of research conducted by the [in]visible project.

[in]visible is a community-based research project involving women (two-spirited, trans, and cis included) without children in their care, who are experiencing long-lasting homelessness in Hamilton, Ontario.

Seventy women participated in the project and shared the ways they have navigated long periods of unresolved homelessness, the life circumstances that led them to experience homelessness, and how gender and identity shaped their survival while unsheltered. In conversations, the women describe the housing they want in detail. Their needs and desires are inextricably linked to their past experiences, which often involve trauma and abuse in addition to homelessness. The women justify their housing needs by describing things that have happened to them or implying them; their stories and the spaces they describe are tightly interwoven.

The housing requirements of these women could be translated into spatial graphics that are detached and technical – drawings with annotations about square footage, plumbing and electrical systems, the location of windows and doors – but my drawings aim to build their stories into the spaces. My style of drawing was inspired by Chris Van Allsburg’s Mysteries of Harris Burdick (1996): a children’s book where narration and charcoal drawings are interdependent. An important and unique aspect of Van Allsburg’s book is that each drawing belongs to the beginning of a story, just a single-sentence prompt. The starting sentence, together with the single image, is given to the reader to construct the rest of the story.

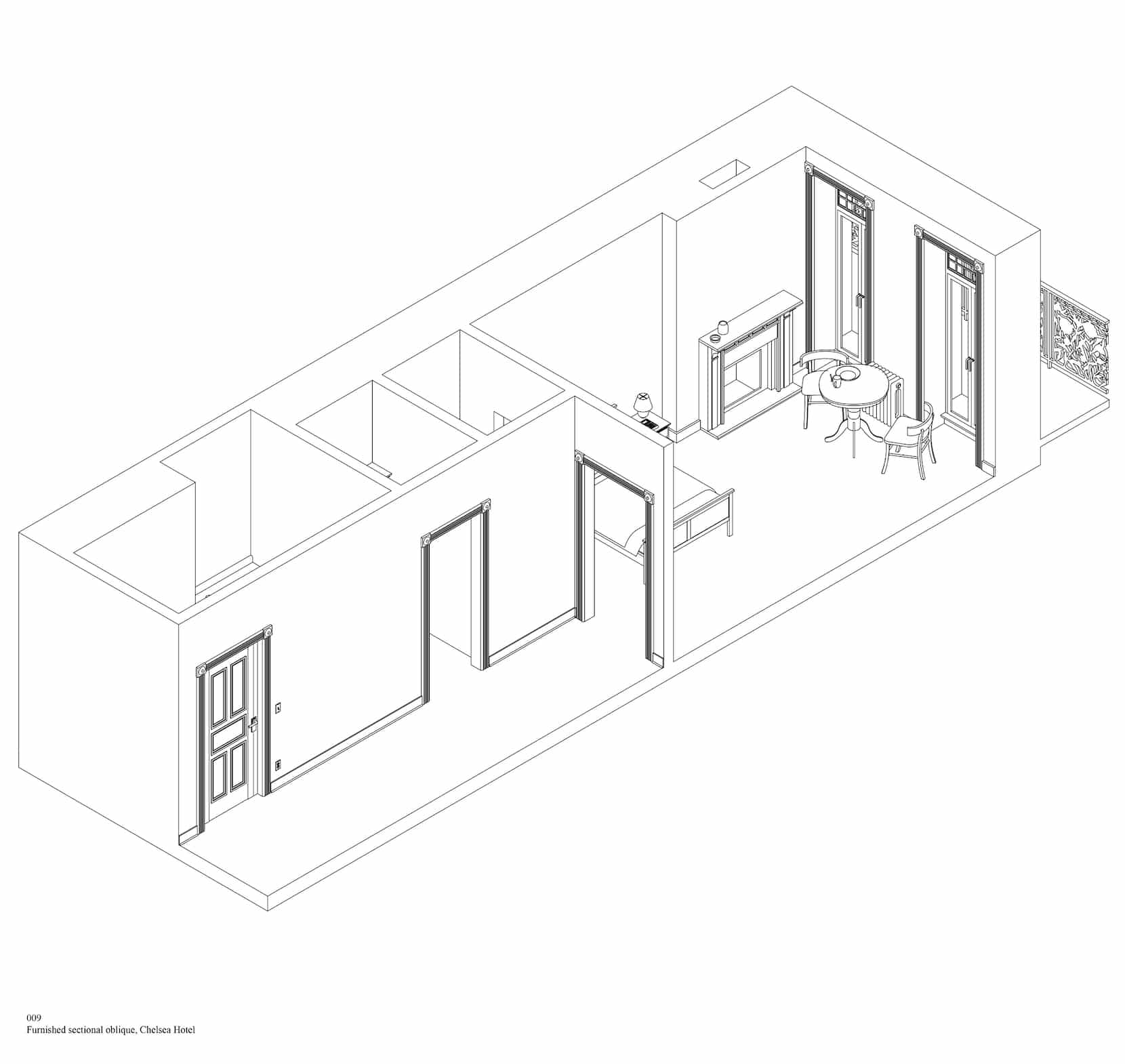

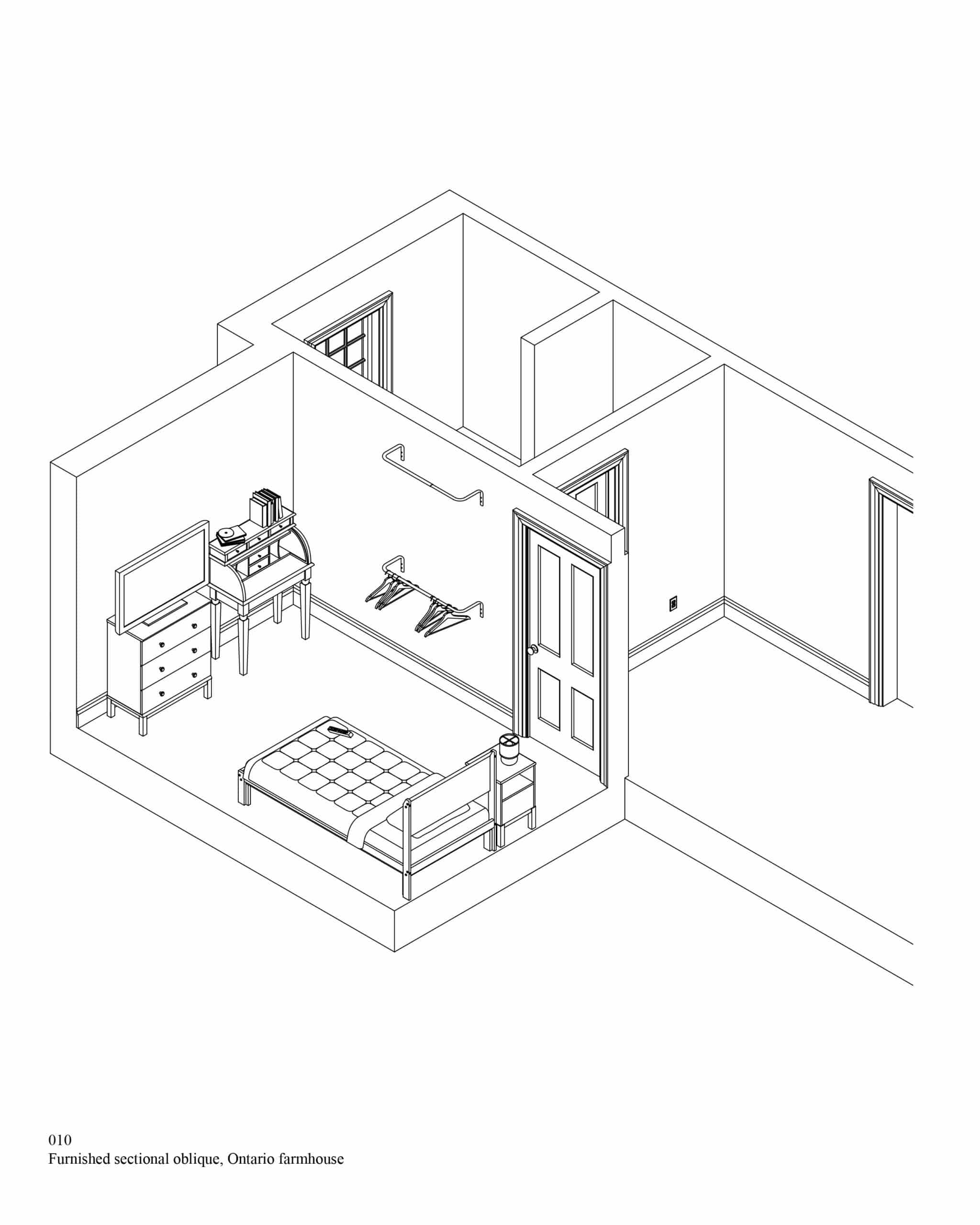

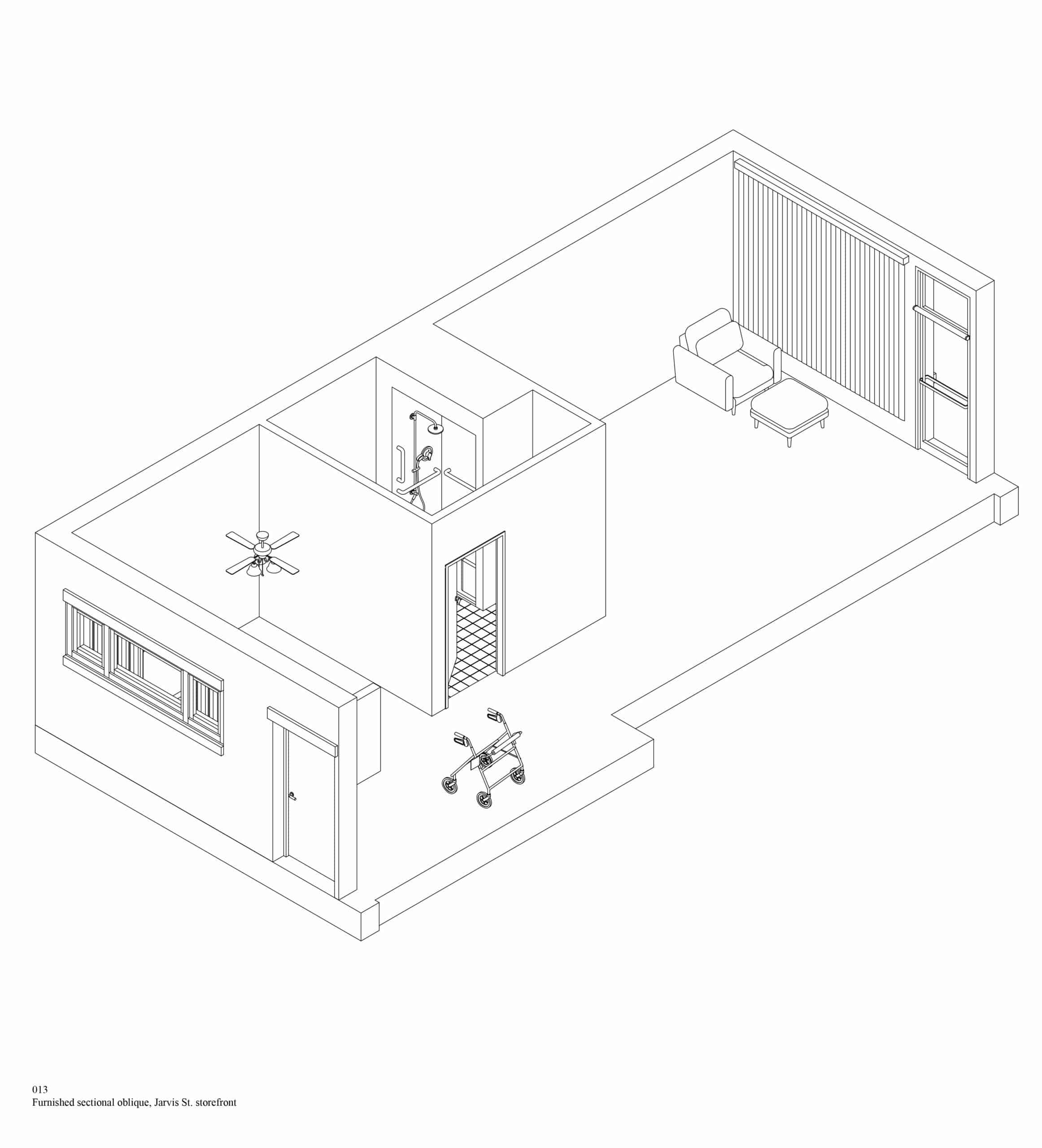

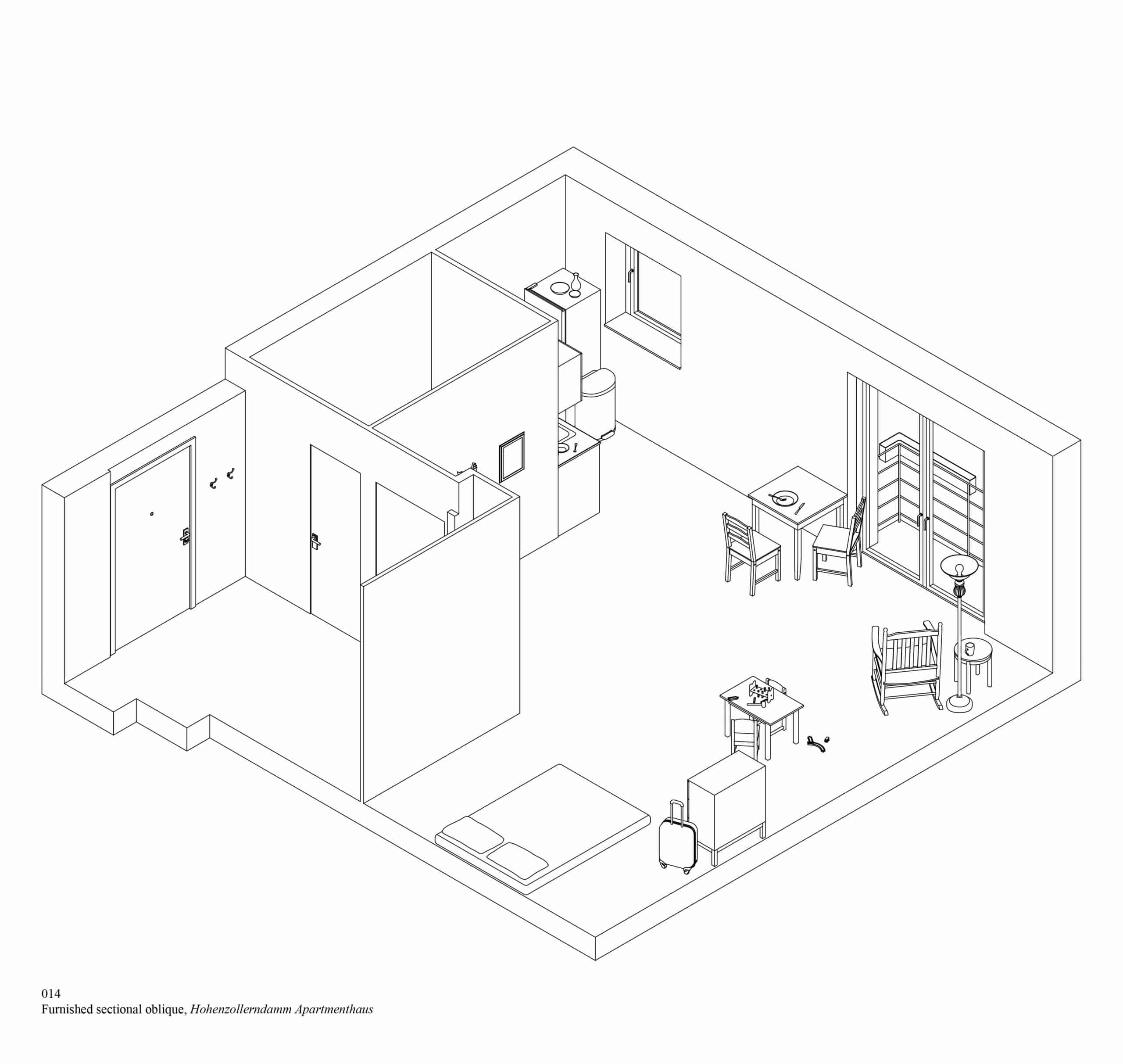

The drawings for the women marry spaces with their stories. In the spirit of adaptive re-use, a kind of ‘space-match-making’, a range of existing spaces were adopted as case studies to situate the women’s stories. Existing spaces drawn include a portion of a century-old farmhouse in rural Ontario, the ground floor in a small, vacant commercial building in a small bordertown in Canada, a residential hotel room in the Chelsea Hotel in New York City, and a modest single-room apartment in Hans Sharoun’s Hohenzollerndamm Apartmenthaus in Berlin. This mixture of ‘authored’ and anonymous architecture was important as it conveyed how the women could and should have access to spaces that can be found everywhere — how accessible emergency housing should be.

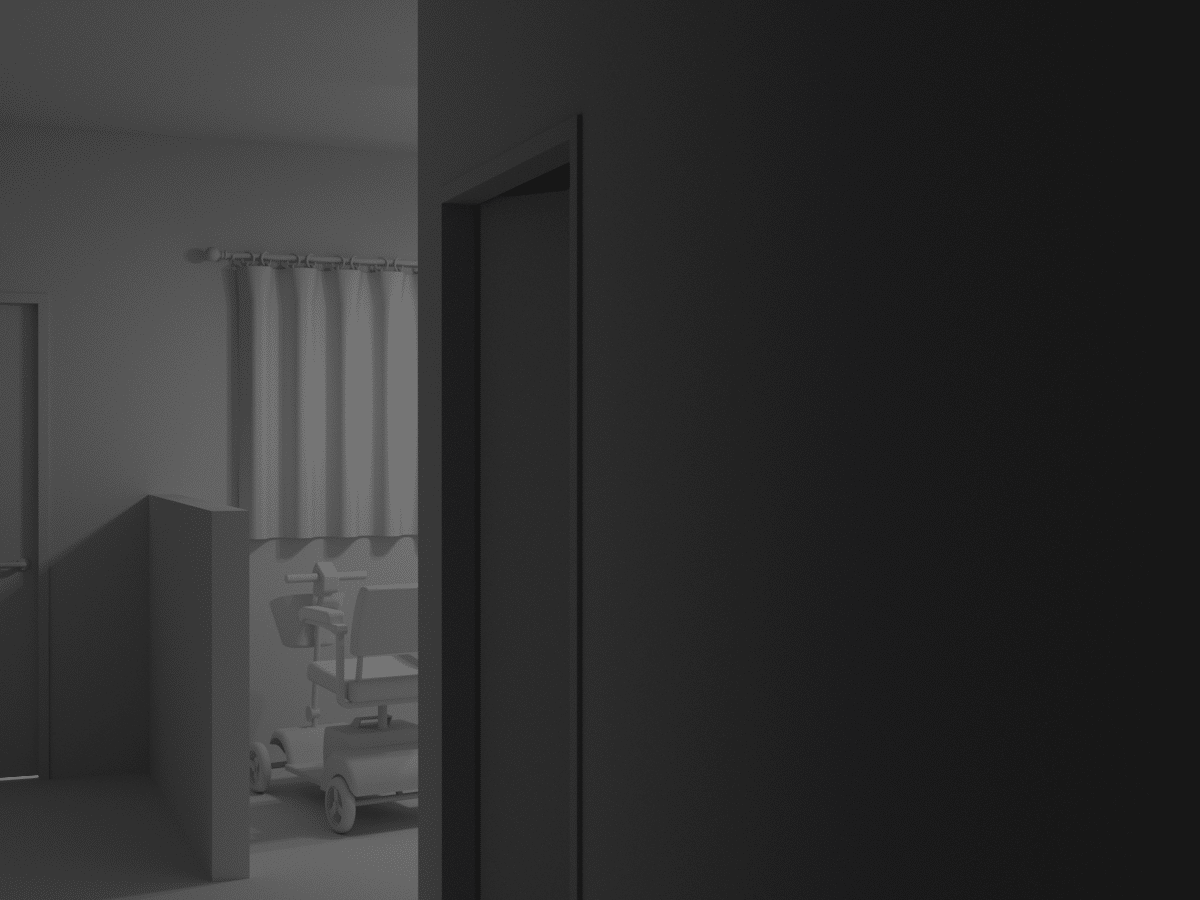

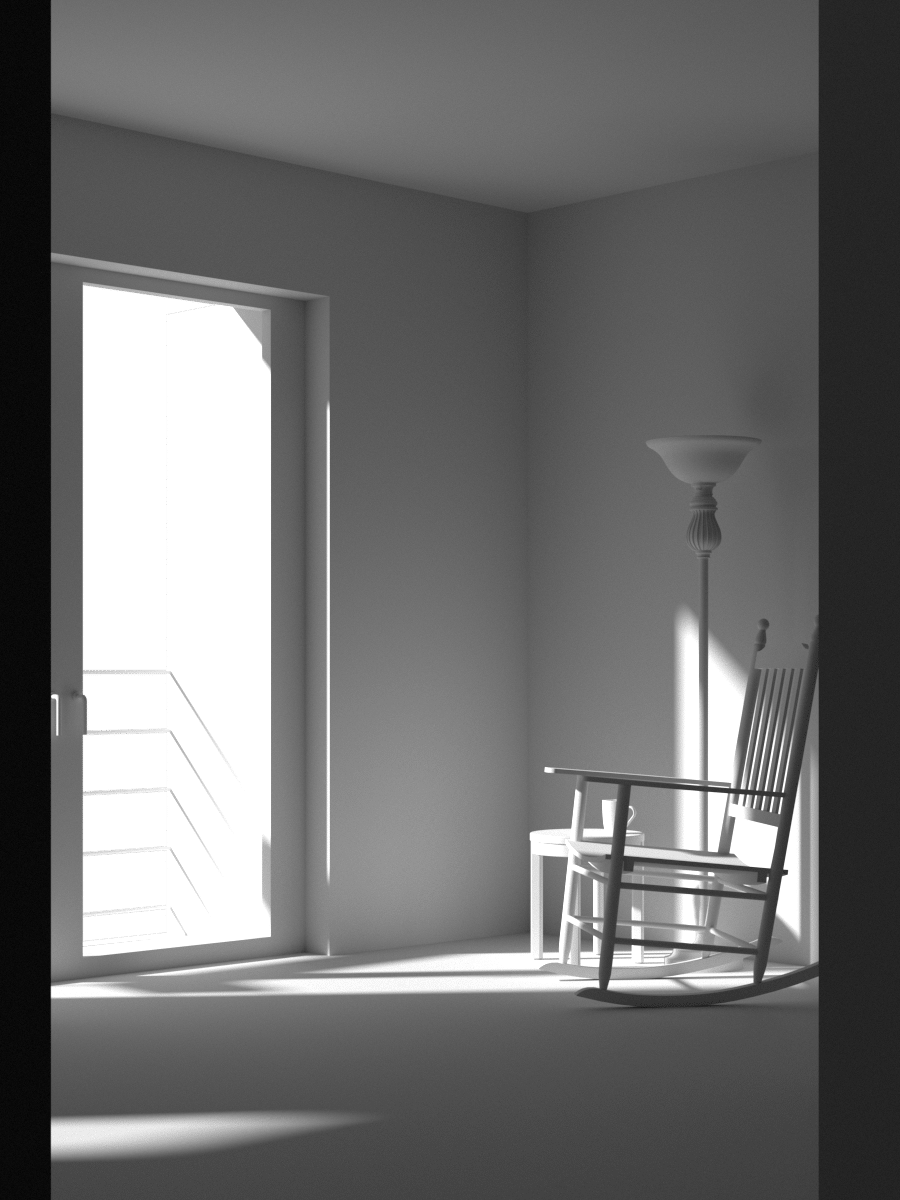

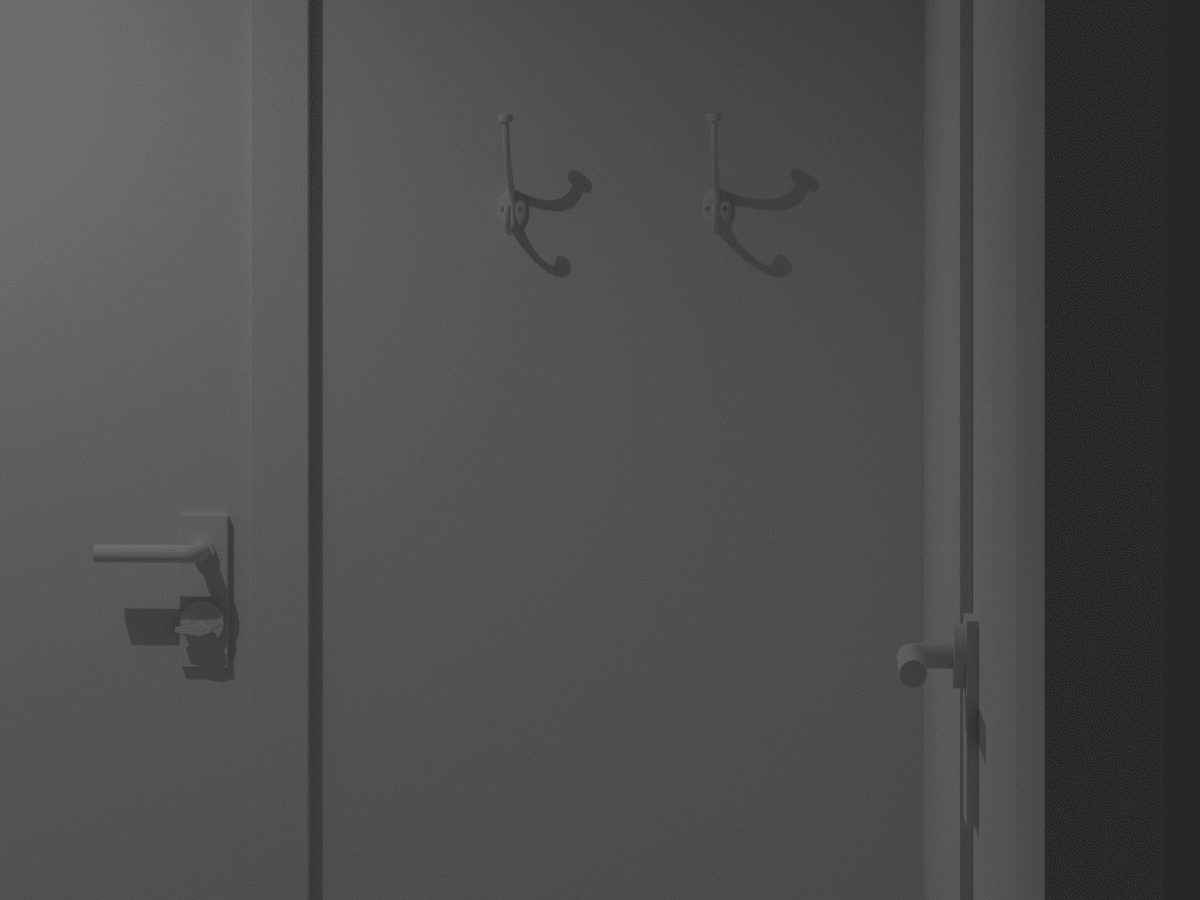

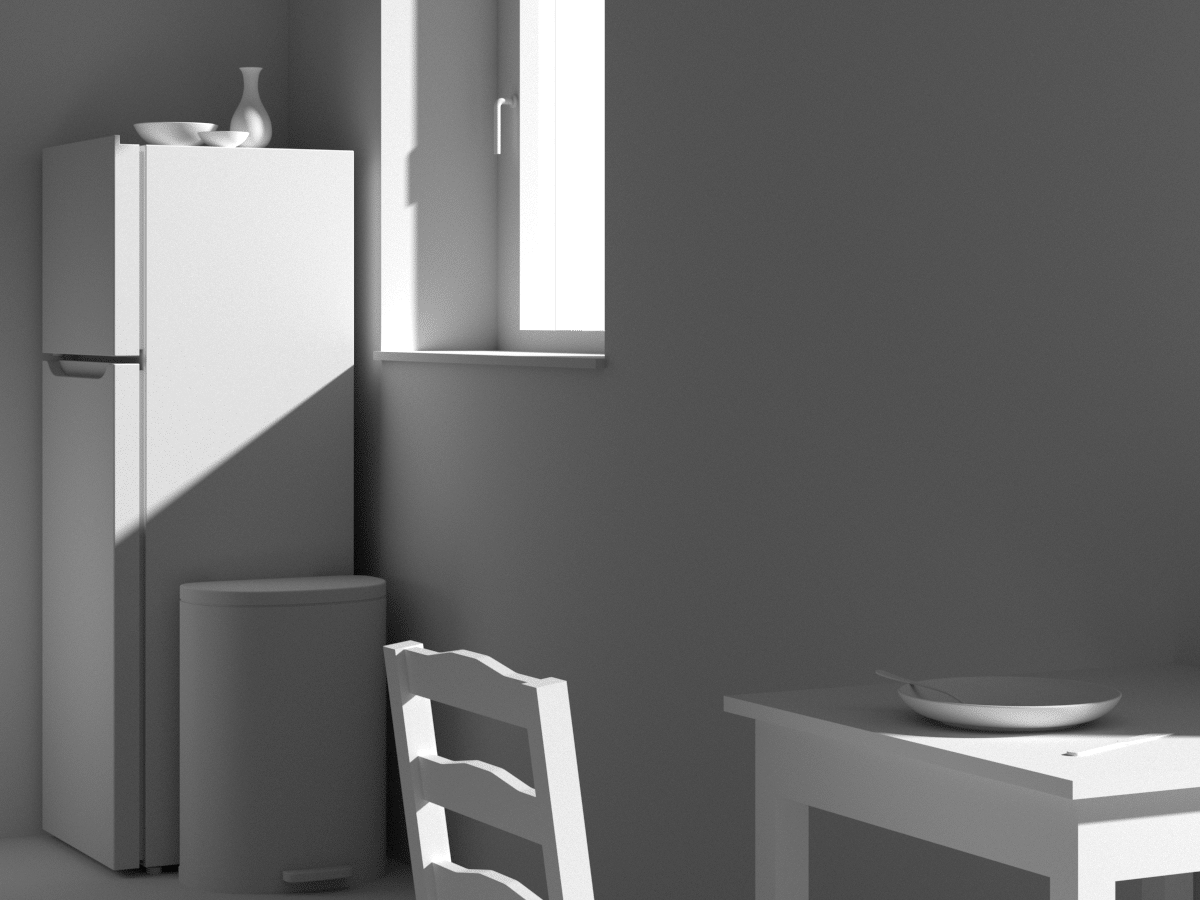

Rather than offer wide-angle, idealised views of interiors, the renderings are close-cropped, greyscale scenes that frame dishwashing liquid sitting beside a sink, the jimmy-proof lock on the inside of the entry door, a telephone beside a bed, and a hotplate plugged-in on a counter. They are highly specific, modest things that the homeless women describe explicitly in their interviews as important attributes of their ideal home. The drawings present mundane, domestic life in a soft, quiet, dream-like way. In the tradition of still life painting, objects in the drawings are carriers of meaning. The fork left sitting on a plate shows that the inhabitant has eaten something, she is not hungry. Dish soap conveys the pride that the women often assert in their interviews about their cleanliness. There is soft furniture to let them rest. The travel trolley in one scene is parked beside a dresser, unpacked and no longer needed. There are windows to open, and secure locks on the doors. The drawings work together as a series. Like film stills, they present moments in an ongoing story where space plays an important role. But the backstories of the women are also present. In scenes with locked doors and closed blinds, we can see fear, worry, and vulnerability.

Sets of conventional line drawings — isometrics and developed elevations — accompany each series of renderings. They show each case study in a straightforward, accessible way, tethering the cinematic interior scenes to a real, concrete space with a legible layout.

Architectural drawings can often be self-interested, made at the service of the space to show what it is like, what it can do, why it’s good, why it’s special. Although a range of architectural tools was used to make these drawings, they are more illustrations than conventional architectural drawings. This is because they were made at the service of the women who need these spaces. The spaces should ask: Can we help? Are we what you need? Architectural drawings are powerful because they can be translated into real spaces that support actual lives.

009

43 years old, 12 years of homelessness

I would be happy with like, I don’t know, say a room and a bathroom and a hot plate, I don’t care say, as long as there is a window to put an air conditioner in or in the wintertime a heater you know, just my own space kinda thing… not too too small, cause I’ve had small, like that room that was on the Mountain where I could barely move and stuff but like a bachelor apartment you know, like nothing fancy but nothing with bugs or anything like that in it, but I do need my own place but I also need to work like I’ve found that I feel better and like I get through the day easier and I feel better about myself having a job.

While for the assault thing like with [name], I need … I would need a phone to contact Victim Services.

While I would need, like say, for the door, I would need those big bolts for when I am sleeping, like I’m not concerned about an alarm and stuff like that but good windows… like if they are old windows I could put screws in them, if I had an air conditioner, I’d have to make sure it was like the wood with like, bolted in and stuff like that, just regular safe um… measures for a place just because I don’t trust those people, just because they had keys to my last apartment.

010

40 years old, 12 years of homelessness

Just probably cleanliness, like a clean one bedroom apartment or even a bachelor. I’ve always wanted my own bed or my own apartment. With a little table or desk to read at. I am happy with just food, enough food to survive on and even reading, just a nice comfortable bed to be warm, reading TV, DVDS, I’d be happy. Safe, something safe too, I can’t live in a bad, scrubby rooming house. I liked (transitional housing for women)… The closeness of the group… other girls, Christmas, just working down the street, putting my little chefs jacket on and getting ready for work. That was the good part.

013

54 years old, 12 years of homelessness

I would need an affordable place, because I have no help with my drug plan. I would need a scooter to get around, or a walker. I would need it to be accessible. And I hope I don’t have to move into a crack house or anything, that’s what I’m afraid of, that I’m going to have to move into a real dumpy place. And you see how clean I am, I’m a clean lady, and I can’t I can’t be around a lot of different people because of my addictions. I also have to be in a disabled place, where I can bring my scooter and my walker in, ‘cause I can’t climb stairs. So it’s gonna have to be either one the main floor or have an elevator… I’m hoping to find a place where I can afford my rent.

014

66 years old, 7 years of homelessness

I’d like a big window, a neat kitchen, a little bit of space, it doesn’t have to be really big, landscaping and a superintendent who does maintenance. It has to be clean and that’s about it. I need to make it safe, for me and my grandkids. I’m on a list for supportive housing in [city in Ontario], a friend of mine from [another city in Ontario] got into the apartment, her whole backyard is looking over the [River name], and its absolutely awesome, and I wouldn’t mind looking out at a river.

This cross-disciplinary drawing project is ongoing. An excerpt was included in Policy and Practice Recommendations: Developing Gender-Based Low Barrier Housing to Address Complex Homelessness published by the Community University Policy Alliance at McMaster University (2022).

Funding for the [in]visible project was provided by Women’s College Hospital (Toronto, ON) and coordinated in collaboration with the Women’s Housing Planning Collaborative of Hamilton. A seed grant from the Creative School, X-University (formerly Ryerson) provided funding for a research assistant, Roxana Cordon-Ibanez, who worked with Stephanie Davidson on the production of these drawings.

Stephanie Davidson (drawings) is a founding partner of Davidson Rafailidis. Mary Vaccaro (research) is a PhD candidate in the School of Social Work at McMaster University, Hamilton.

– Paul Notley