Drawing on Ideas

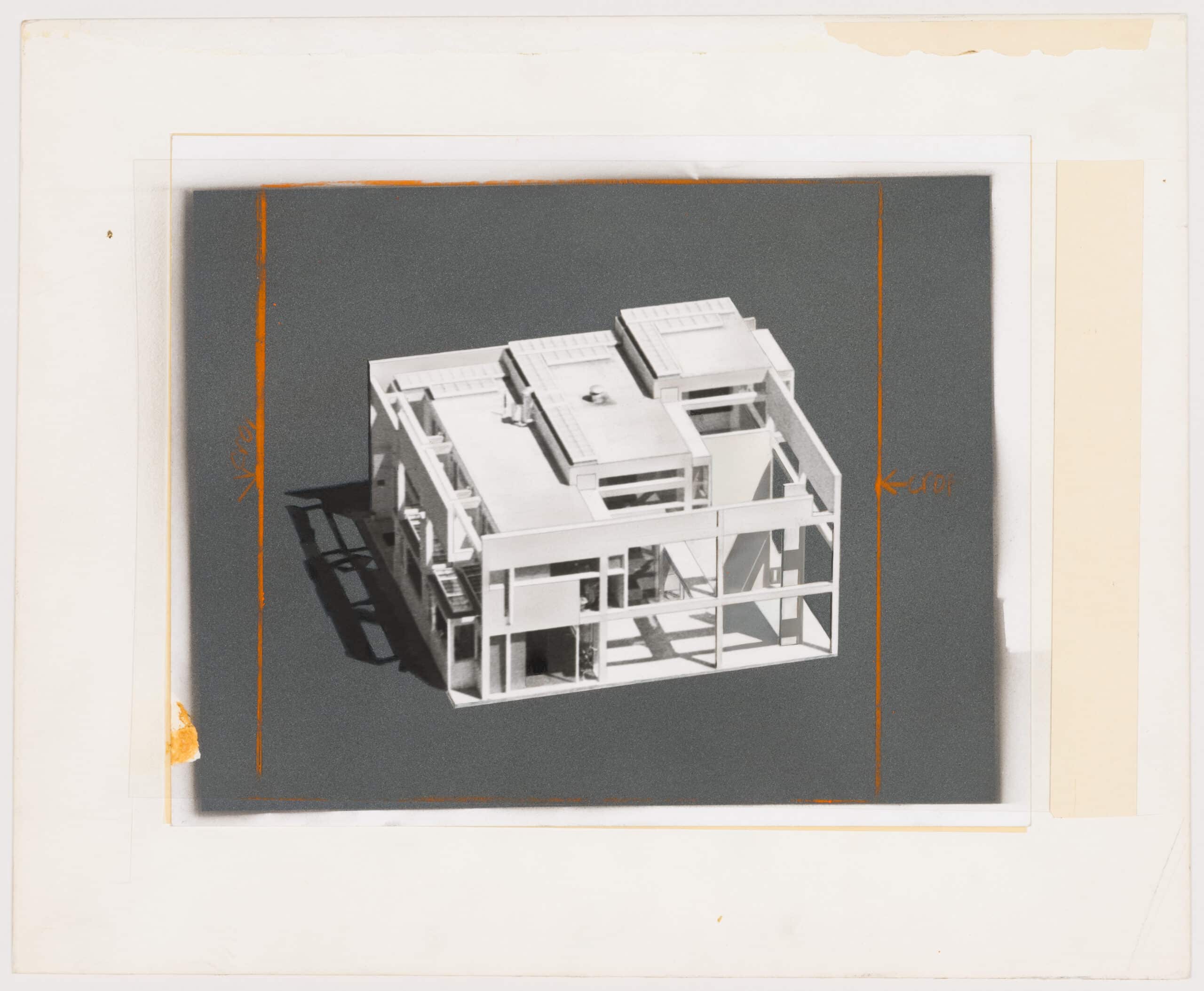

In 1972, when Peter Eisenman’s House II was published in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, the editors confused a photograph of the built work for an image of a model. The house was located in Southern Vermont, and had been shot from a low angle against a uniform grey sky with a snow-covered hillside in the foreground. Without cast shadows, the grainy black and white print shows little detail that would indicate a building constructed and inhabited. No chimneys, doors, shingles, handrails, porches, stairs or window frames, nothing that hints at domesticity. The abstract white structure, intended to recall clean modernist concrete work, is in reality made of whitewashed stucco over plywood. Only the appearance, at the extreme left of the image, of bare tree branches silhouetted against the sky suggest the actual site. But then again, those could easily have been scale trees made of wire.

Far from being upset by the mislabeling of the photograph, Eisenman embraced the idea. ‘House II sheds its scale specificity by employing conventions of the architectural model in the actual object,’ he wrote. ‘The house looks like and is constructed like a model.’ Cardboard architecture, he called it, in a curious echo of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Around this same time, he instructed an assistant to take some aerial photographs that might reinforce this ambiguous status between the model and the built object. Randall Korman rented a Piper PA-28 Cherokee from the White Plains airport in Westchester and flew to Hardwick, Vermont. Sarah Herne writes that ‘Korman would bank the plane’s wings and remove his hands from the gears to snap photographs, before retaking the controls and circling the plane back again to repeat the shot. The plane’s droning engine was audible from the ground, just loud enough to draw the client’s son to the window, where he was captured in the frames—a small but visible figure pressed up against the glass pane.’[1] Back in the studio, all traces of context were airbrushed to a neutral dark grey, while preserving the cast shadows. The result looks like an architectural model photographed on a tabletop, although in this instance, the skylights, roof vents and, if you look closely enough, that diminutive figure hint at its reality as construction.

For Eisenman, the idea is everything. Drawing is not a way station, or a technical instrument leading to the definitive statement of the building, it is an equivalent (and sometimes more powerful), manifestation of an idea. Drawings, models, buildings, diagrams and texts, Eisenman wants to say, all operate on the same conceptual plane, equal in value and importance. Each one teases out different aspects of an abstract concept that is the primary motivation of Eisenman’s architecture.

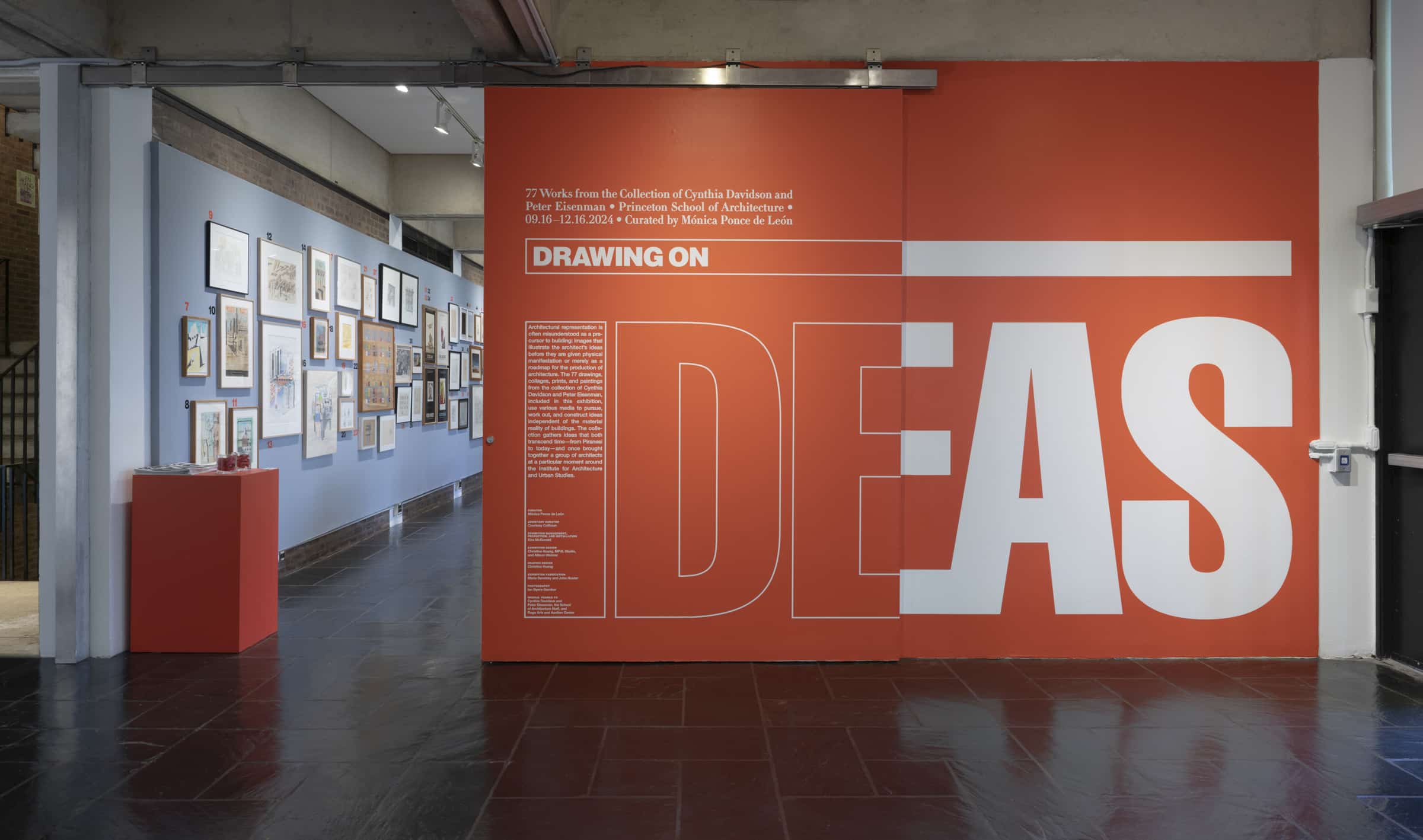

It is no surprise then that an exhibition of drawings from the collection of Cynthia Davidson and Peter Eisenman, curated by Mónica Ponce de León with Courtney Coffman, and on view at the Princeton School of Architecture through December 2024, is titled Drawing on Ideas. In many ways, however, the insistent presence of the individual works—drawings, prints, typescripts and ephemera—push back on that organising framework. They assert their character as objects, and call attention to the hand of the author. Very few could be described as being transparent to an idea, and most of those are by Eisenman himself. There is plenty of aura in the gallery, and history too.

The exhibition title appears at a super-graphic scale on the entry wall and sliding door of the gallery, rendered in Oppositions orange. The walls have been painted a neutral grey, and the 80 objects in the show are hung densely on the walls or distributed in vitrines. The first thing the viewer encounters is an array of sketches and drawings by Aldo Rossi from the 1970s: versions of the Analogous City, the Modena Cemetery, and what Rossi calls ‘Paesaggio Urbano con Ricordi Privati’ (Urban Landscape with Private Memories).

Anchoring the exhibition, visually and historically, is a collection of Piranesi engravings on one wall (including the assembled plates of the large plan of the Campo Marzio), and opposite that, a series of Le Corbusier lithographs from the 1950s and ’60s. These two facing walls mark out the poles of Eisenman’s ideological worldview: the spirit of the twentieth-century avant-garde juxtaposed to the breakup of Enlightenment certainties (as read through the writings of Manfredo Tafuri) in Piranesi’s delirious piling up and breaking apart of the ruins of the classical past. Although it is not the same drawing, one of the adjacent Rossi sketches recalls the image printed on the cover of the 1979 MIT Press translation of Tafuri’s Architecture and Utopia.

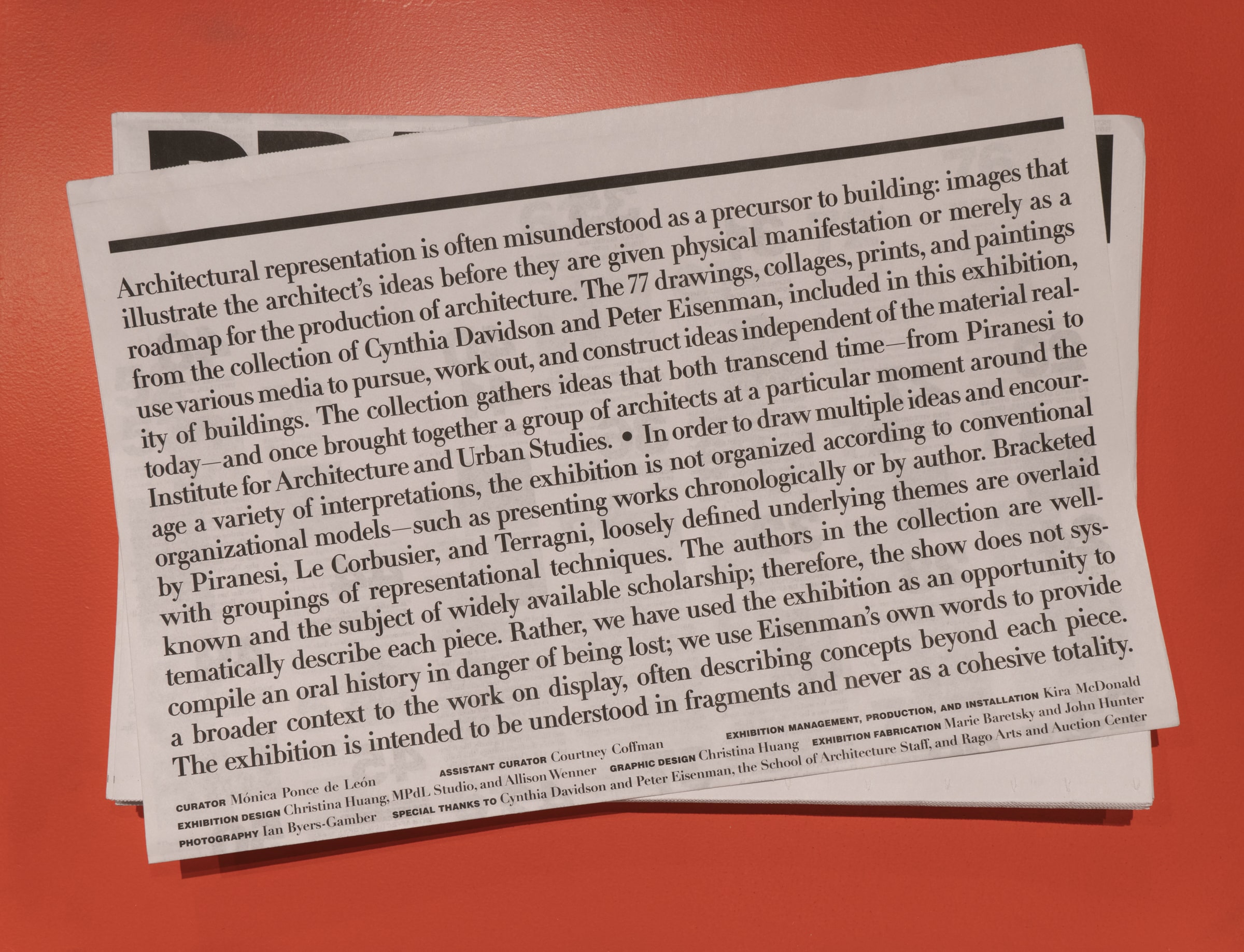

The Piranesi aside, the earliest works in the exhibition are blueprints and sketches from Giuseppe Terragni’s office that Eisenman carted from Como to Cambridge with Colin Rowe in the late 1950s, when he was at work on his PhD thesis. ‘20 or 30 rolls of working drawings from the Terragni office,’ Eisenman says, sticking out of the sunroof of his Volkswagen. ‘Had it rained it would have destroyed everything.’ The latest, in a kind of odd symmetry, is a drawing by Franco Purini based on Eisenman’s Berlin memorial.[2] But these are outliers. The exhibition is a snapshot of the 1970s, or more specifically, of Eisenman’s experience of the seventies. Think the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, think Oppositions and Skyline, the Triennale of 1973 and the Biennale of 1976 (where Eisenman was curator of the American contribution), and think of the rise of European theory in American schools of architecture. ‘We have used the exhibition as an opportunity to compile an oral history,’ the curators state, and this is apt. Instead of wall texts or project descriptions, each of the objects in the exhibition is published at thumbnail size in a tabloid handout (the typography of which recalls Skyline), with Eisenman’s reminiscences of the authors and the context in which the work was executed or collected. Every work in the exhibition is reproduced as a postcard, arrayed on a long low shelf against the windows. Visitors are encouraged to take as many of them as they wish, and a thick red rubber band is provided to secure the large wad of postcards. The cards are replenished daily, the size of the stack an index of the level of interest each image attracts.

If the focus is tight, the range of work is diverse. The exhibition is densely hung, and each work is in dialogue with others around it. Aldo Rossi, John Hejduk, Michael Graves, Mathias Ungers, and both Krier brothers, Leon and Rob are well represented. There are a number of delicate watercolours by Massimo Scolari, beautifully drawn. There is a small sketch by Tony Vidler of an architectural folly that reminds viewers how well Tony drew, and a pair of pastel landscapes by Pier Vittorio Aureli. For Eisenman’s 80th birthday, Wes Jones made a drawing in the manner of Ed Ruscha: the word ‘absence’ in white on a grey gunpowder ground, creased, torn and folded, as if discarded. It fooled me. I didn’t know Peter collected Ruscha, I thought. Too bad it got damaged.

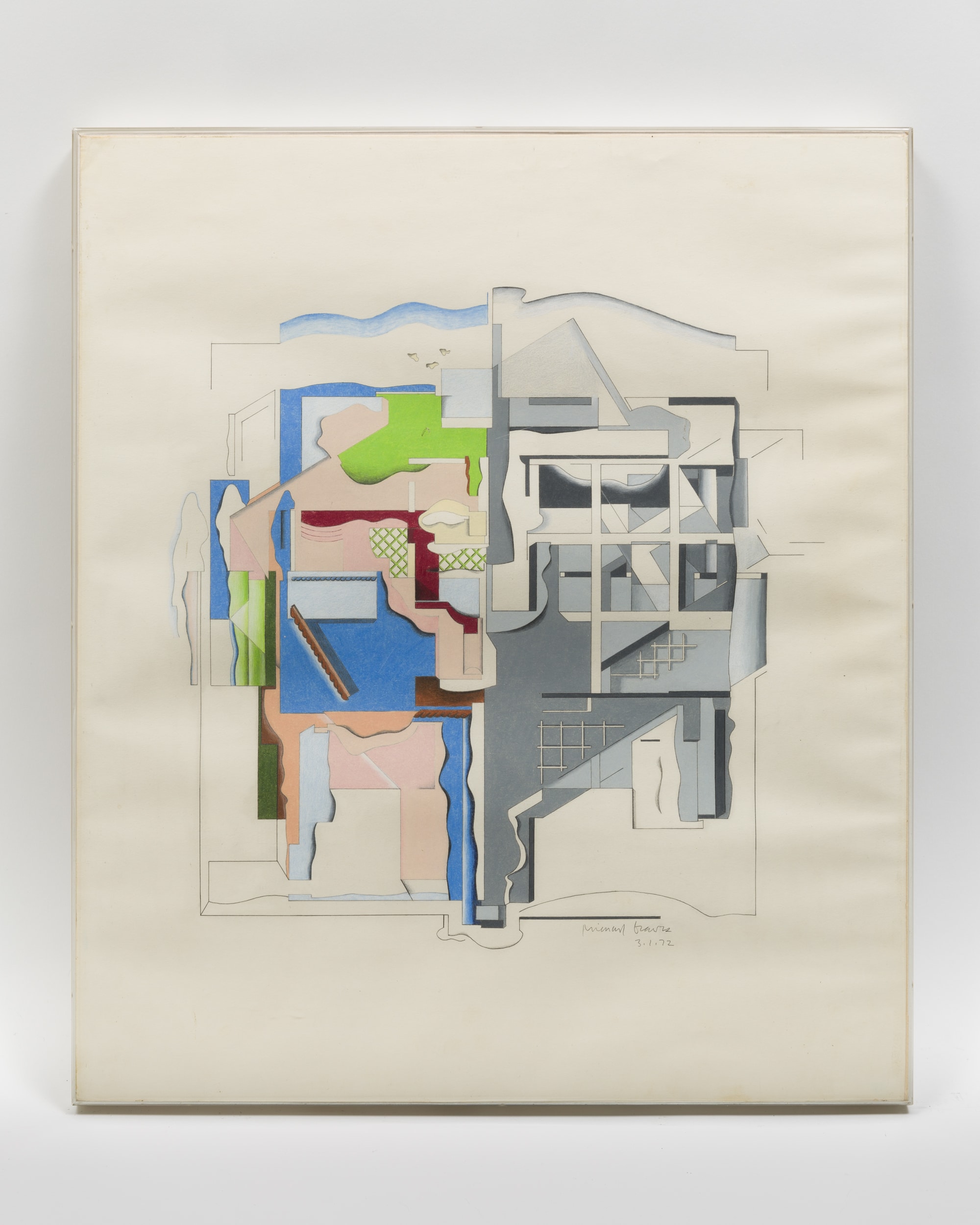

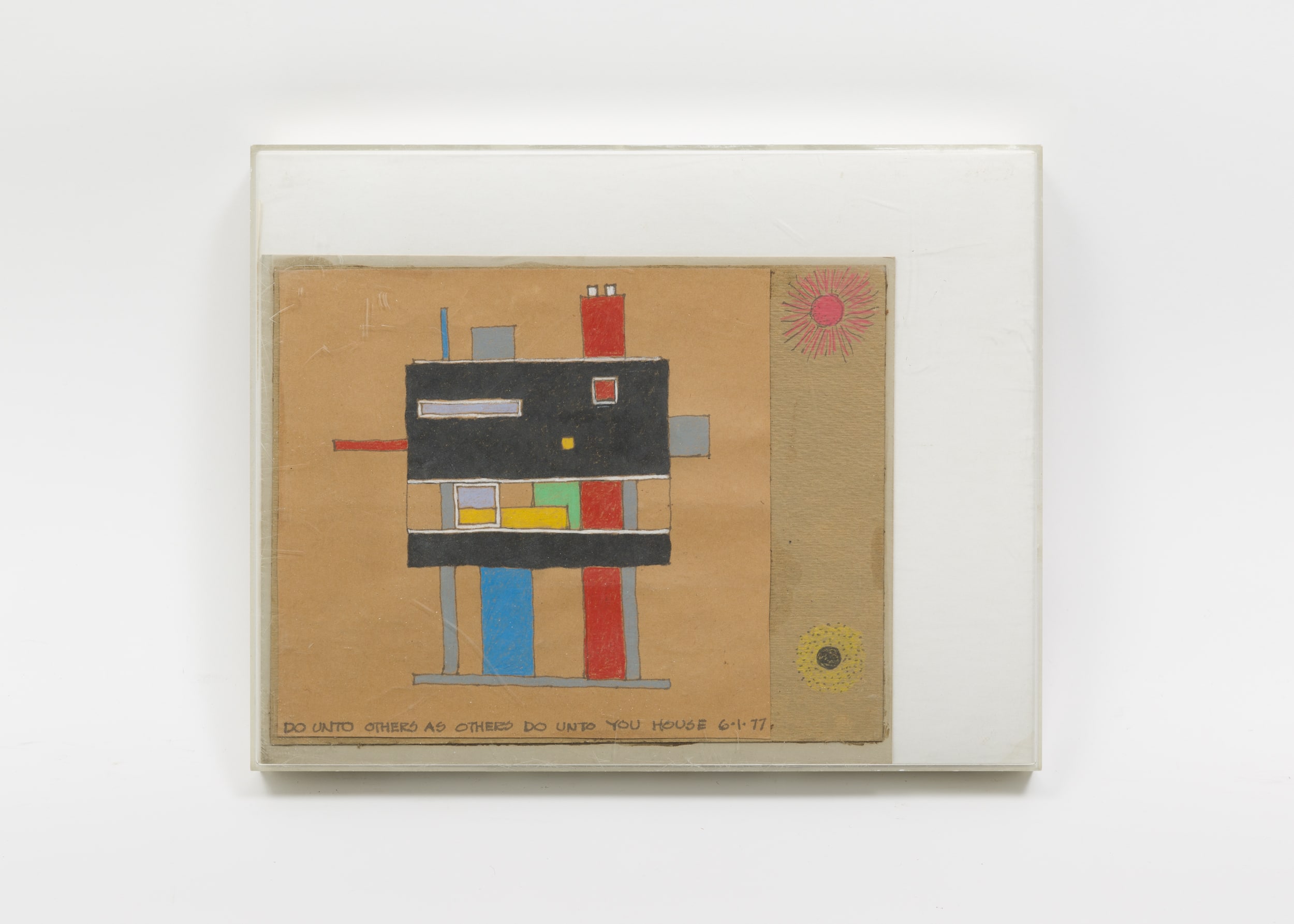

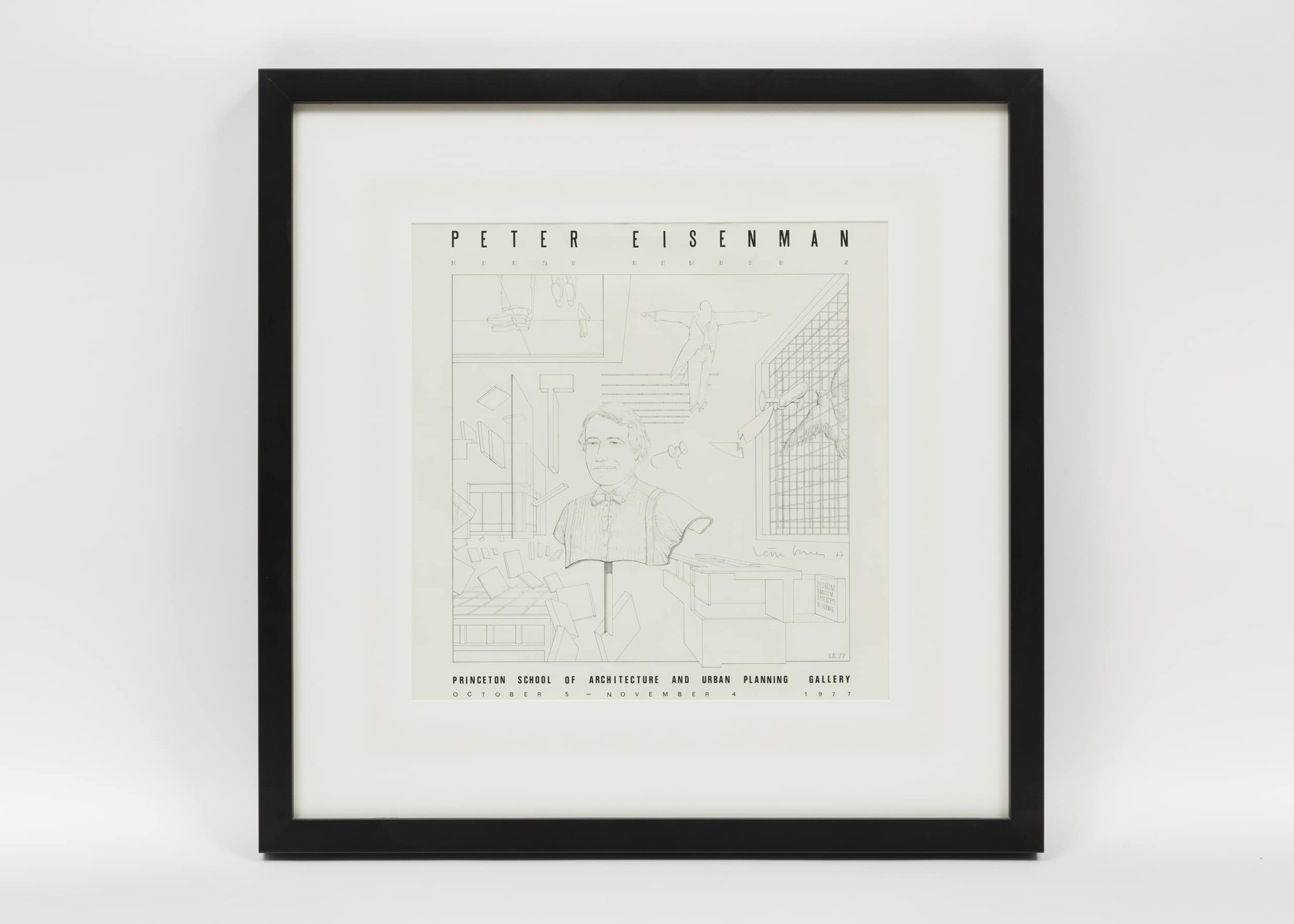

One of the pleasures of the exhibition is seeing unfamiliar drawings of familiar projects: An early pen sketch on the back of an envelope showing Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo; a large array of coloured plans and elevations of John Hejduk’s Todre House, as well as a small elevation drawing entitled ‘Do Unto Others as They Do Unto You House.’ There are original drawings that became familiar as reproduced images: a 1972 drawing by Michael Graves for the cover of an issue of Progressive Architecture and Graves’ collage for the Institute’s Idea as Model catalogue. Leon Krier’s portrait of the architect, drawn for a poster announcing an exhibition of Eisenman’s work in Princeton in 1977 is a dense allegory of references and allusions. The drawing shows Eisenman, striped shirt, bow tie and braces, trapped in a gridded cage of his own making. Outside (or is it an adjacent cage?) is a dove, wings beating against the bars. The architect’s glasses, a broken carving knife, and various architectural fragments float weightlessly in the air, perhaps an allusion to Eisenman’s habit of ignoring gravity and turning things like stairs and columns upside down. Near the top of the image is a faceless figure in the pose of the Winged Victory that could be a stand-in for Krier himself. ‘PETRUM AMICUM APOCALYPSIS FORMAE’ reads the inscription on a tombstone on the lower right.

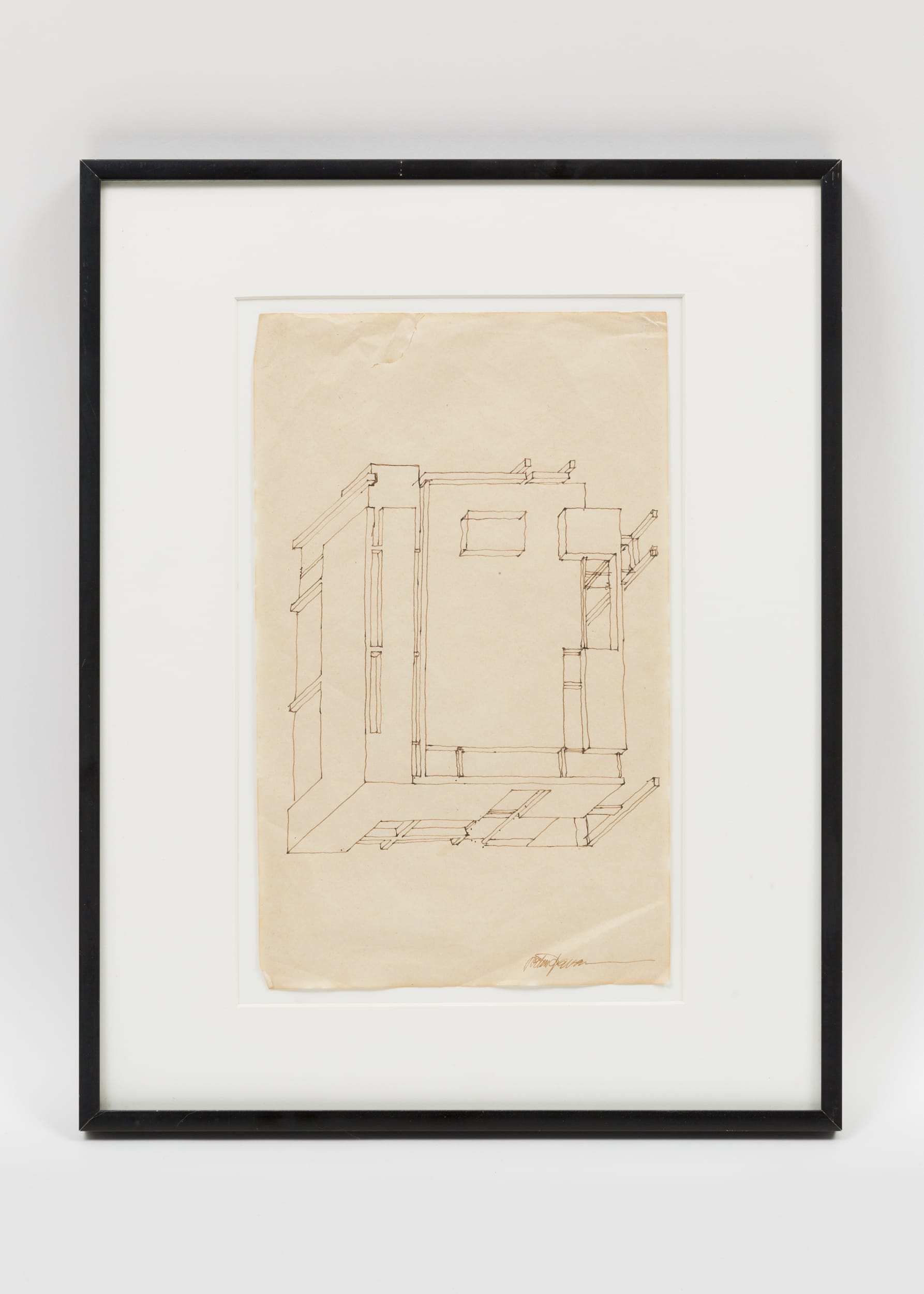

Eisenman’s own sketches, fragments of blank wall panels and trabeated frames, show an underlying architectural (not to say tectonic) intuition that is a less-often recognized aspect of his early work. His violations of the logic of the frame are powerful precisely because the rules and expectations of the tectonic are familiar and intuitively felt. On the other hand, drawings by Krier, Scolari, Rossi and Graves speak to the lively dialogue that played out between Eisenman and those whose work was quite different from his own.

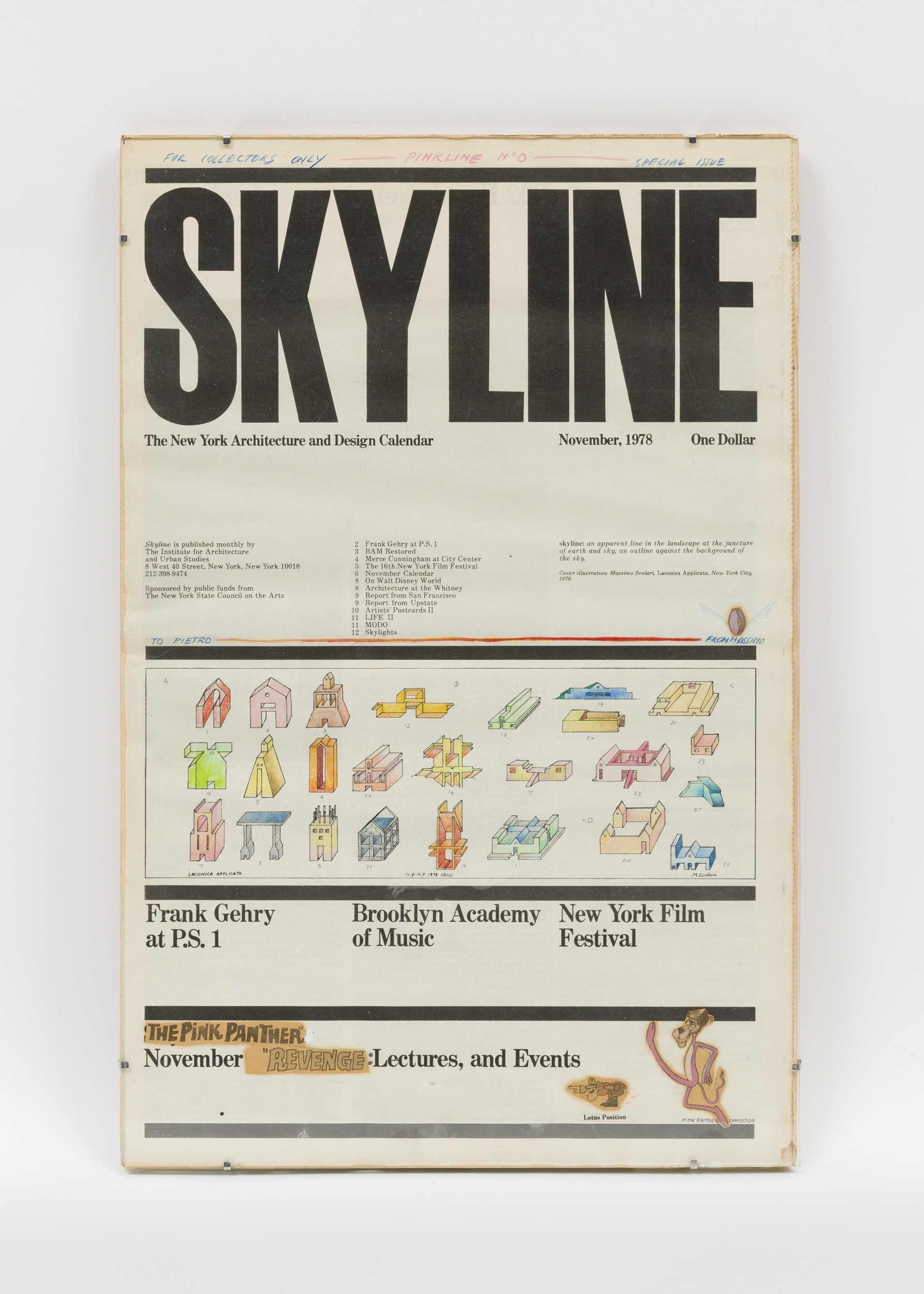

Some of the most interesting material in the exhibition could be described as ephemera. There are signed posters for exhibitions by Ungers, Rossi, Krier and Scolari, many of them hand colored; a letter from Aldo Rossi to Peter Eisenman, and typescripts for Eisenman’s ‘Editor’s Introduction’ to the English version of The Architecture of the City, as well as the text of the translation itself, by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman. My personal favourite is a cover of Skyline from November of 1978. Massimo Scolari has coloured the array of his line drawings printed in the middle third of the sheet, and added a new heading: For Collectors Only – Pinkline No. 0 – Special Issue. At the bottom, the announcement of ‘November Exhibitions, Lectures, and Events,’ has been modified to read ‘The Pink Panther, November REVENGE, Lectures, and Events.’ Collaged into the lower right corner is a cartoon version of the crafty feline (familiar from the opening credits), about to whack Inspector Clouseau with his long tail. The hapless policeman is bent over, his backside vulnerable, in what a collaged caption describes as the ‘lotus position.’[3]

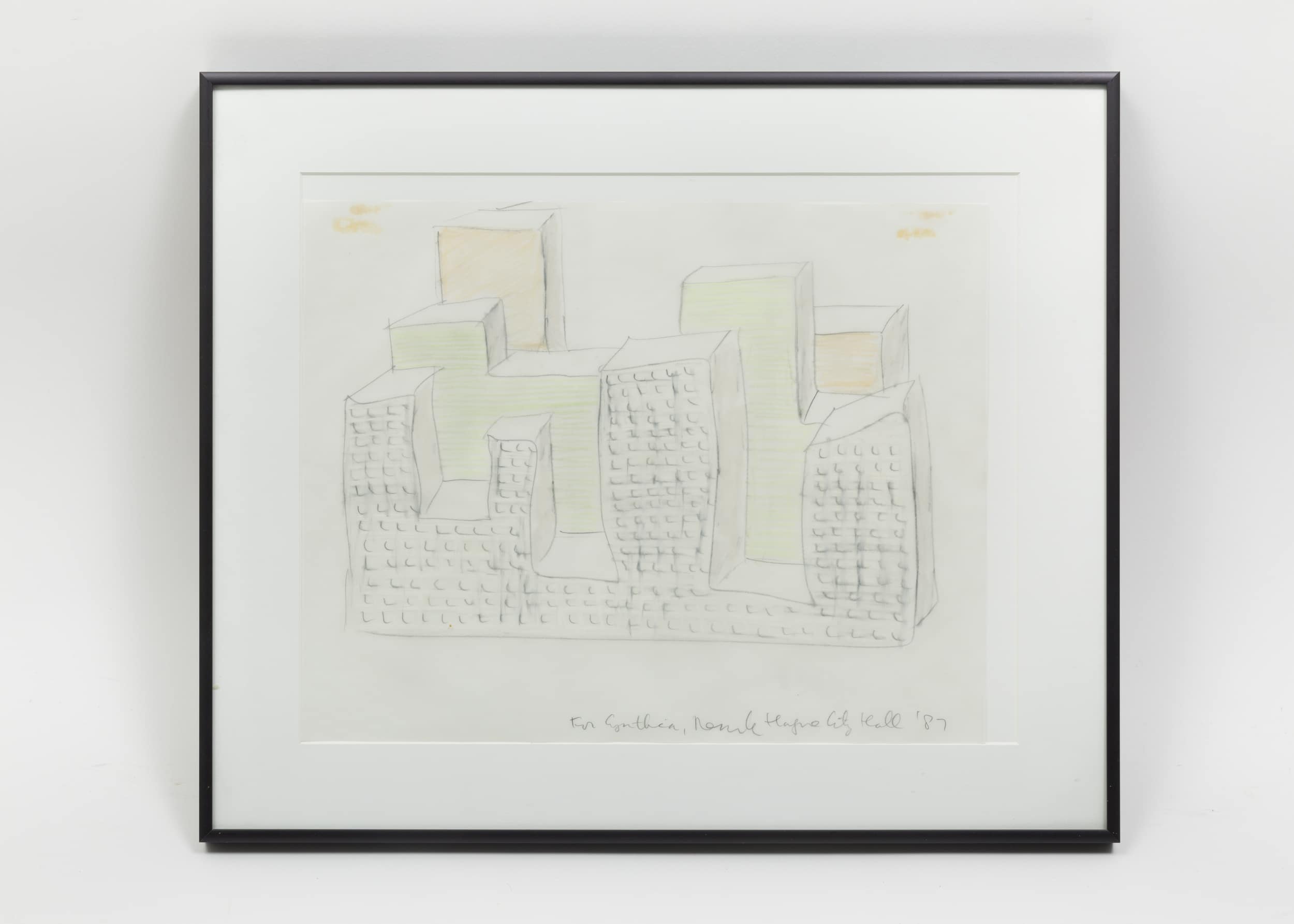

The exhibition underscores the role of drawing as a fluid medium of thought: a place where architects can set down and test ideas, a medium always incomplete, propositions awaiting translation or response, in the form of buildings, projects, texts, or other drawings. But for an exhibition dedicated to ideas, this is a very personal show, intimate almost. Many of the drawings carry dedications, to Peter from Rossi, Graves, Ungers and Krier; to Dr. E from Hejduk; to Cynthia from Rem, and from Peter to Cynthia. Perhaps the real force of the exhibition is neither in the drawing as an abstract cipher of an idea, or as an auratic trace of the author’s hand but of the inextricable intertwining of the two. The personal is political we like to say; in this case, the personal is rendered conceptual.

Notes

- Sarah Hearne, ‘Model for Falk House (House II), CCA Articles, <https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/72422/model-for-falk-house-house-ii> [accessed 7 November 2024]. The earlier Eisenman quotation in this paragraph is taken from the same source. In another famous instance, Eisenman’s 1970 text ‘Notes on Conceptual Architecture: Towards a Definition’ (a conscious reference to Sol Lewitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art of 1968) consisted of four empty sheets with fifteen floating numerical annotations scattered across the blank space, referring to the ‘reader’ to the notes at the bottom of each page. See: Design Quarterly, No. 78/79, published in 1970 by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

- Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, 2005. Curiously, it is in reference to Purini’s drawings of his memorial project that Eisenman remarks, ‘Manfredo Tafuri said to me, in a very precise moment… “Peter, you can write all you want, etc. But if you don’t build, nobody will care about what you write.’” In the end, he says, ‘I built enough to satisfy Tafuri.’

- The Revenge of the Pink Panther came out in 1978. And for those unfamiliar with the period, ‘lotus position’ no doubt refers to the Italian architectural journal Lotus International. There are quite a few of these insider references in the exhibition; I am quite certain, for example, that the iconography of Krier’s portrait of Eisenman is more complex and involved than my account suggests, and that there are other stories about the work in the exhibition yet to be told.

Stan Allen is the principal of SAA/Stan Allen Architect and former Dean of Princeton University School of Architecture.