Drawing Research Platform, Somerset, 2023, ENAC Summer Workshop

– Alberto Johnsson, Arthur Masure, Daniel Nitsche, Toby Pullen and Alexander Turner

During a one-week summer workshop at Shatwell Farm, students from the EPFL, alongside young architects from the UK, explored drawing as a key tool of architecture and engineering. Through research into the Drawing Matter collection and the construction of survey drawings, the workshop used drawing as a corporeal form of measurement to observe the environment of the farm. Below are reflections on the experience by two of the workshop groups.

Reflection by Alberto Johnsson, Daniel Nitsche and Alexander Turner

To decide

The location under study was a vast field nestled to the southwest of Shatwell Farm. When we arrived at the farm, we chose to leisurely explore the fields and meadows. Eventually, we ascended to the pinnacle of a hill, which marked the farthest point of our survey. Upon turning around, a breathtaking panoramic view unfolded before our eyes. This vista was beautifully framed by its natural boundaries: a lush forest enveloping the fields, well-worn pathways etched by countless footsteps, and the picturesque backdrop provided by the barn. These natural confines concealed the remainder of Shatwell Farm, effectively obscuring it behind a curtain of trees, immersing us in an entirely new environment. In that moment, we resolved to meticulously delineate these boundaries. We carefully positioned a drafting table and bench near the origin point at the hill’s summit. This origin point was carefully chosen beside a majestic tree atop the hill. From this strategic vantage point, we embarked on the task of measuring the boundaries: to the south, a thicket of bushes marked the property’s edge, while to the north, a graceful curve of bushes led downhill. To the east, the imposing forest sliced through the property’s side, directing our gaze toward the captivating view of the farm.

To build

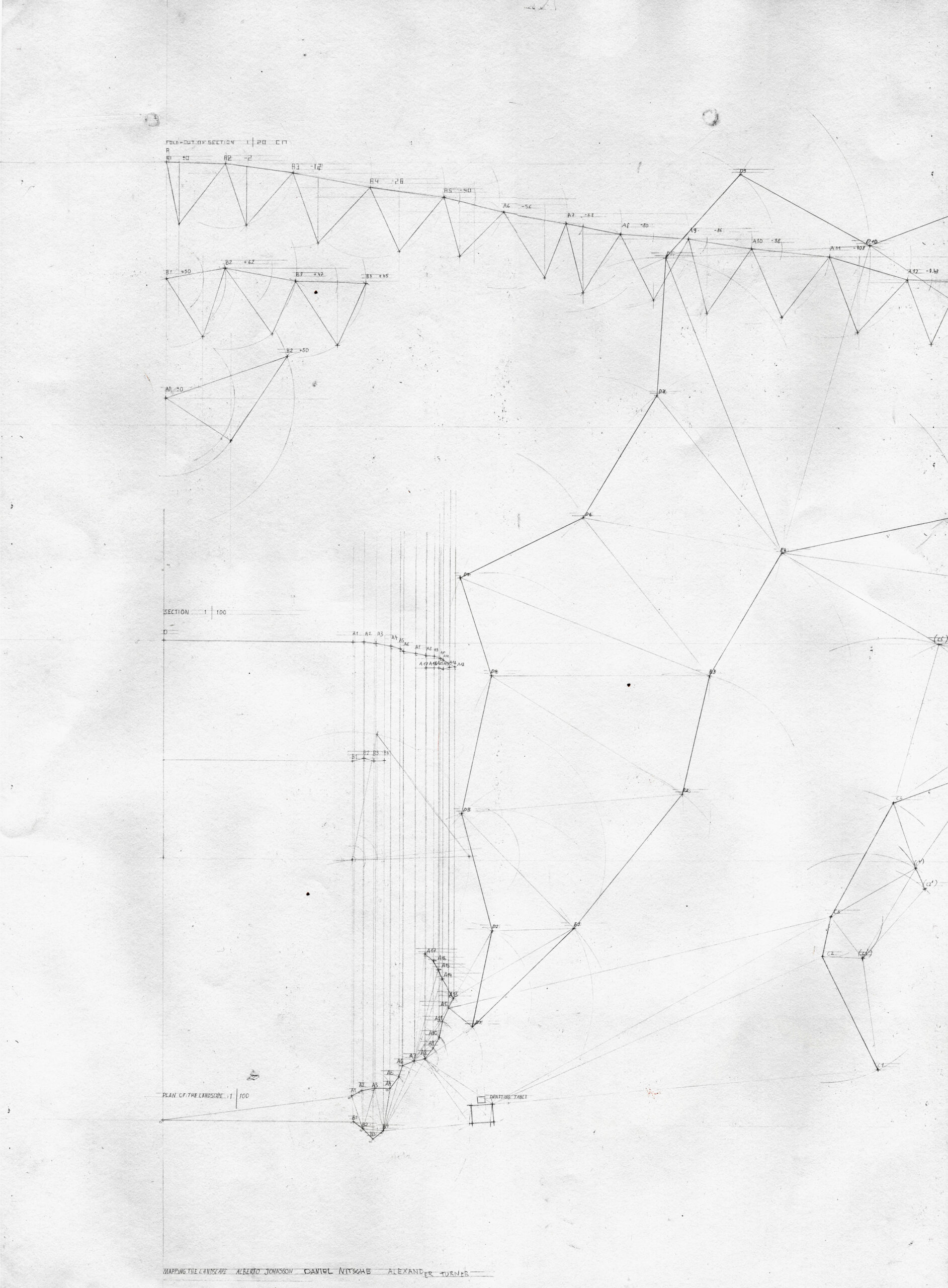

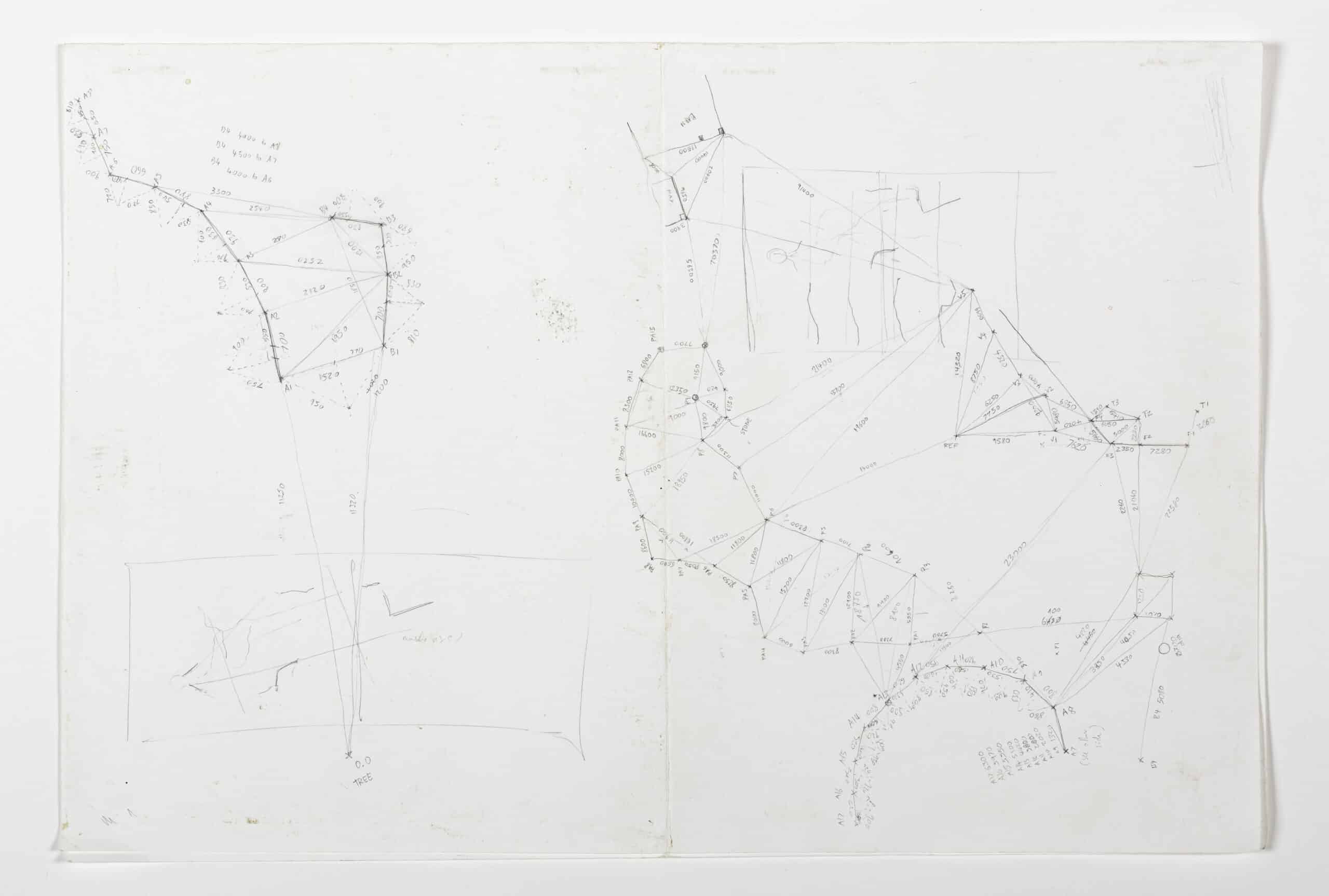

We began our evaluation by closely examining our immediate surroundings. Notably, there were thickets of bushes flanking the sides of the slope, and we decided to commence our measurements from this point. To facilitate our task, we fashioned small pyramids using one-metre-long wooden sticks, and we meticulously traced the contours of the terrain with points to approximate its shape. Subsequently, we calculated the distances between these pyramids and positioned them in space using triangulation techniques. In addition to determining the horizontal boundaries, we also took into account the variations in elevation between the hill and the slope during this process. To achieve this, we created a vertical pendulum by suspending a weight from the apex of a triangle. This ingenious setup allowed us to establish both vertical and horizontal measurements within our drawings.

To walk

First, we focused on precision before transitioning to broader measurements. After completing our assessment of the bushes, we ventured into the expansive field. Our objective was to gauge the pathways formed by the frequent passage of people and the vast forest that delineated the hill’s contours. To accomplish this, we strategically selected points from these natural features and employed triangulation techniques, using small pyramids we strategically placed. The rhythm of our movements resembled a coordinated dance, much like that of a compass. Alberto remained stationed while Daniel advanced to the next designated point. Meanwhile, Alex served as our coordinator, recording the measurements we gathered. We continued in this manner until we reached the barn, which served as the backdrop to our survey.

To draw

The act of drawing paralleled our measurement process, following the same systematic approach. Triangulation played a pivotal role in geometrically resolving our measurements. However, it’s crucial to emphasise that none of this would have been possible without the tangible presence of paper. The vertical triangles were constructed using the compass’s flexibility in conjunction with angles and rulers. The three of us engaged in a synchronised drawing effort, each with a specific role. For the creation of elongated triangles, we improvised by having one person hold the ends of two interconnected strings while another person meticulously noted the point where the knot concluded. At one juncture, a question arose: ‘Why isn’t your table perfectly depicted as straight on the drawing, and why are the angles set at 90°?’ Undeterred, we persisted, remaining faithful to the underlying principles that guided us. In doing so, we showcased both the limitations and the potential of our methodology as we painstakingly charted the entire landscape.

Reflection by Arthur Masure and Toby Pullen

The Summer Workshop group was tasked to observe—to perceive as if for the first time—the voids within the Shatwell Farm landscape. Through the precise realisation of a singular, continuous drawing, the succession of choices made during the five-day process lead to our perception of ‘infinite luminous nuances'[1] in the territory in which we worked: through the act of observation, the elements we thought we ‘knew’ at first glance to be ordinary, banal, and everyday, took on meaning, a meaning expressed in— and understood through—each drawing that we made.

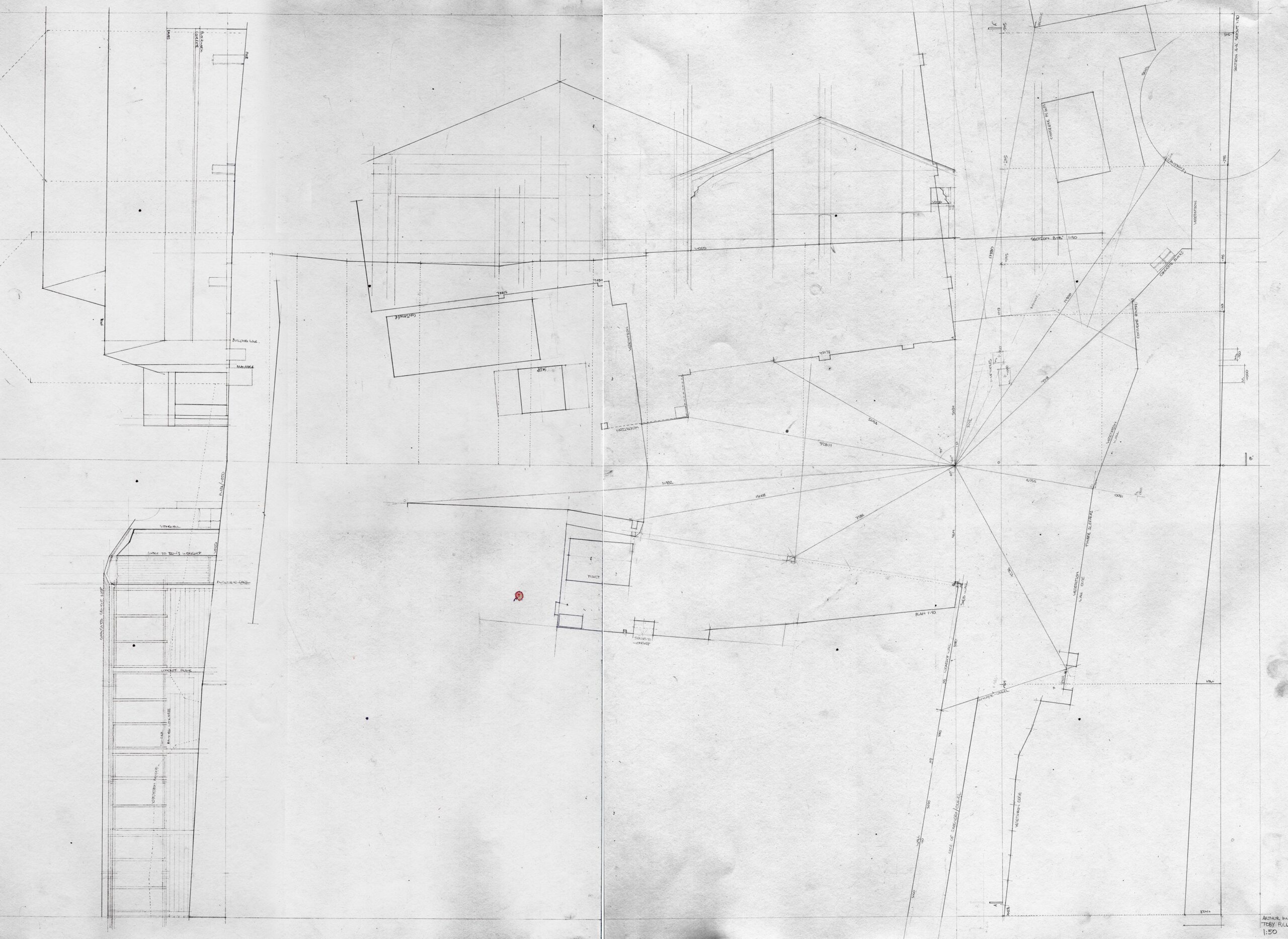

We decided to emphasise the theme of the territorial void as the ‘negative’ space between the buildings in the area of highest density of the farm, and thus what we perceived to be its centre. In this central ‘void’, we established a point of origin—a point zero—where four concrete slabs meet to form a cross. From here, we made measurements of distances and angles were made to varying reference points with a piece of string; the reference points positioned on building edges and landmarks breaking the intersection between horizontal and vertical planes: ground and building. Returning to point zero each time, the understanding of the site grew with each drawn line, first in our sketchbooks, and then quickly moving onto the final paper.

Drafting these reference points onto paper produced a matrix of control points in plan, from which further measurements could be taken on site. As the drawing developed, the density of linework intensified within the space between buildings whilst building forms became empty space; as such demonstrating a focus on void rather than volume. Whilst idiosyncrasies in this process existed, such as defining where void becomes building in instances where the ground plane continues between uncovered to covered space, these were resolved through careful attention to lineweight and type.

Ground levels were measured through an ad hoc laser, string and wooden board instrument, which allowed for two sections and elevations to be added to the drawing, intersecting the planar linework with further layers of information. As the information grew, voids—including manholes and openings—were emphasised through intentional lineweight variations. Whilst the drawing began as a plan, the elevations and sections provided additional necessary information about the expression of the void’s bounding ‘walls’.

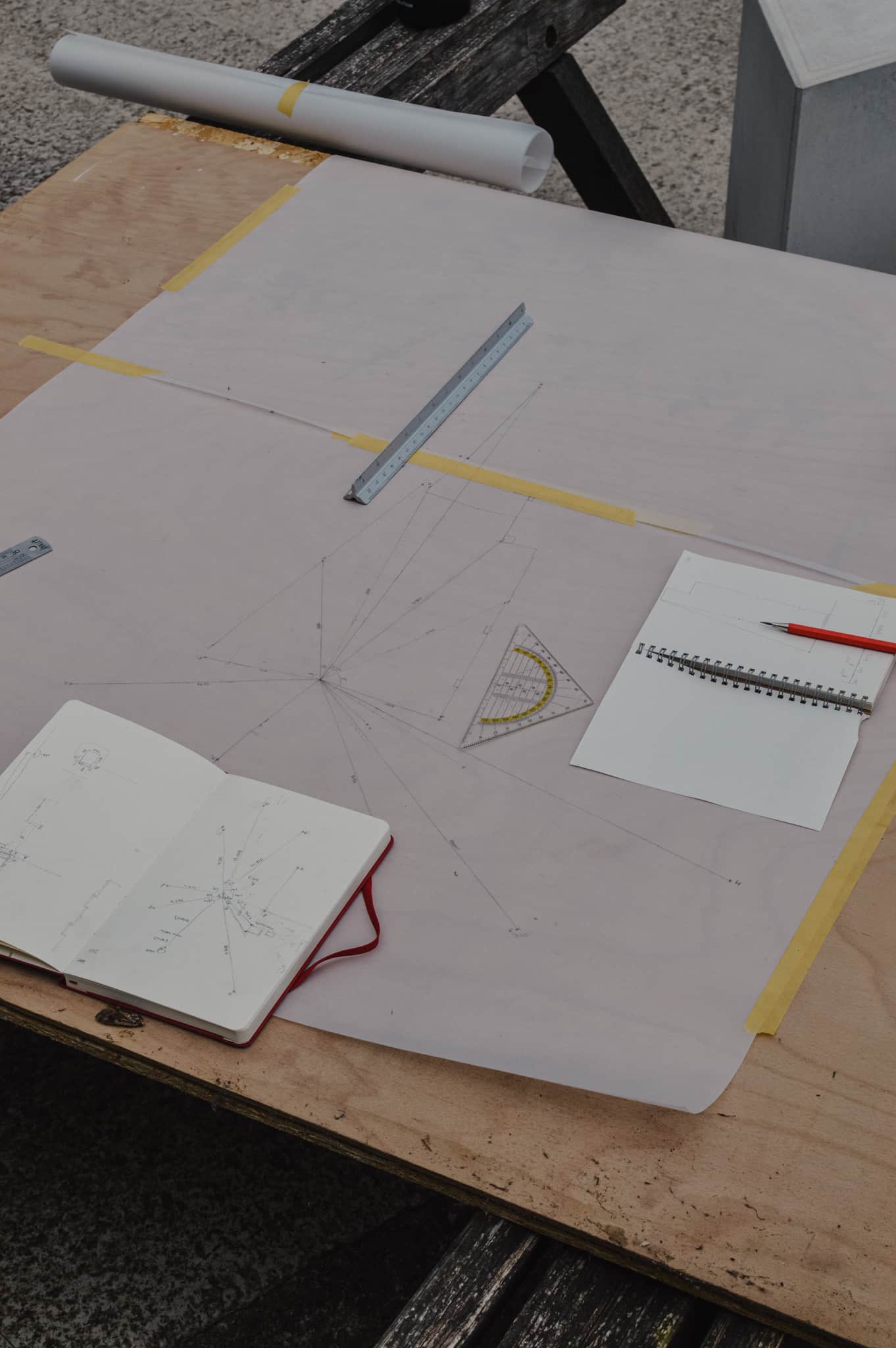

The drawing was exposed to the site for five days, and the paper therefore expresses a history of the site through marks left behind by insects, bird droppings, rain drops, and wind, all adding a poetic texture to the drawing itself. Graphite fingerprints around the perimeter form a reminder of the drawing’s scale when viewed digitally. As the weather changed and our interest in particular areas and measurements progressed, we made a series of ad hoc trestle table arrangements. The fluidity this gave allowed for the accommodation of changing weather conditions and the inhabiting of specific areas of interest. Occupying the Gowan Shed, with a stove fire on a rainy day, was particularly memorable!

Collaborating as a pair brought together varying perspectives and experiences. The drawing is the result of a fluid process, with two pairs of collaborating hands developing from faint draughting lines into the confident, expressive lines of void. Through a pragmatic approach, the drawing’s resultant aesthetics were only a product of the act of observation, of gathering precise information through inhabiting the site. In this way, the drawing is an expression of the site’s territorial and built nuances, perceived over a week-long observational process. As a product of observation, the drawing could never be deemed finished, with no clear boundary or limitation.

- Fabio Cruz Prieto, De La Observación (Viña del Mar: biblioteca Constel de la EAD PUCV, 1993). Translated from French by the Authors.

Participants in the ENAC Summer Workshop

EPFL students: Mageline Duquesne, Adrien Signoret, Leo (Zhang Quan Ng), Arthur Masure, Tom Kobayashi, Alberto Johnsson, Daniel Nitsche, Alexis de Aragao, Myriam Daiz, Alice Dareys, Hervé Laurendeau.

UK Team: Alexander Turner, Toby Pullen, Ruben Giannini, Lance Soleta, Natalie Hase, Owen Neve.

Teaching Team: Patricia Guaita, architect and Lecturer, EPFL, Switzerland; Raffael Baur, architect and external Lecturer EPFL, Switzerland.

Invited expert: Manuel Montenegro, architect.