Eric Parry: Iran, 1974

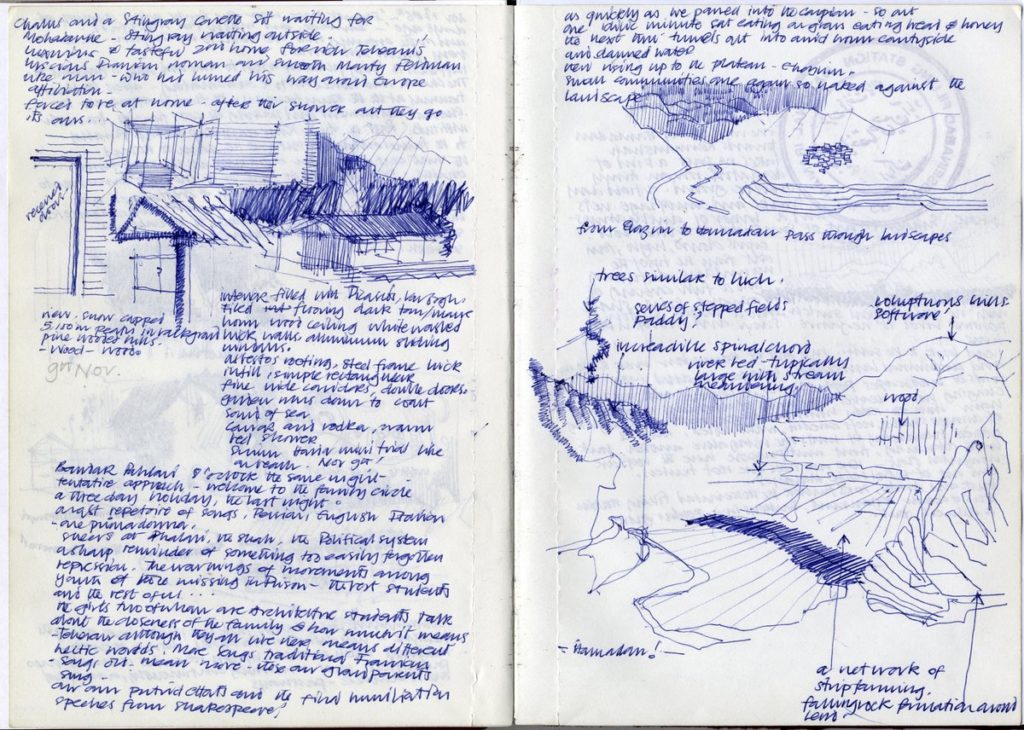

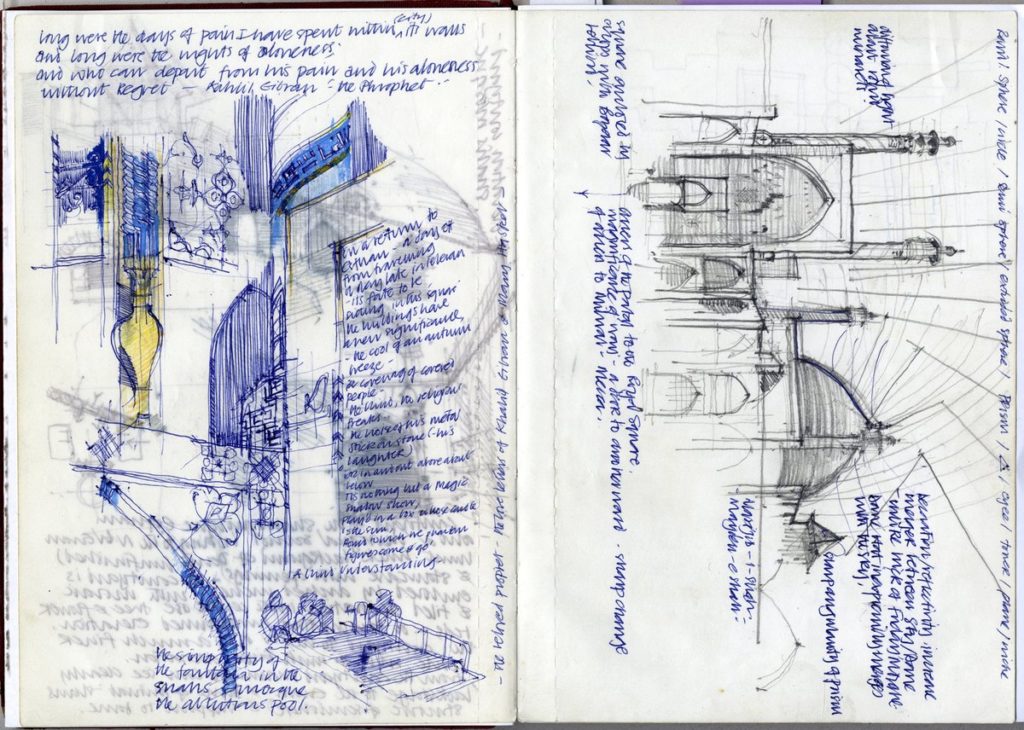

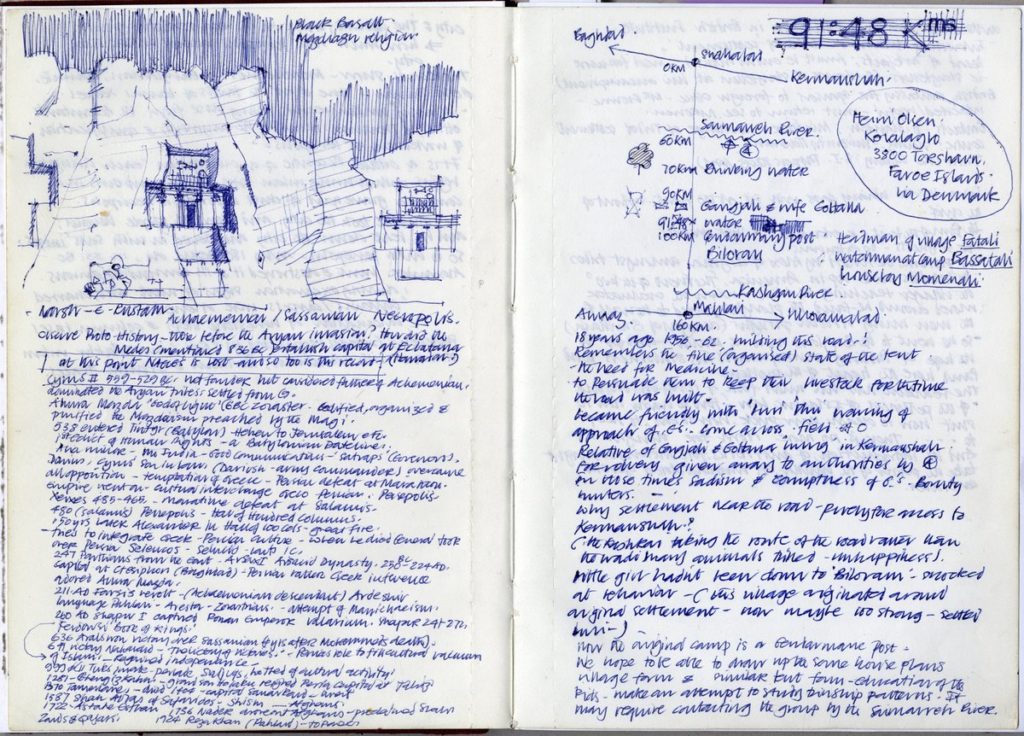

If I now open the page – this sketchbook is different to rest because at that time, one had time. There was no planning to any of these. No A to Z or intention of a grand plan. For the months involved there is not much evidence, only a hint of the daily struggle. I bought this book in the Newcastle art store. Here it is on a Friday morning in August, a road trip through Europe to Ankara and particularly the Gecekondu or squatter housing there – I had been doing research on this subject at the Architectural Association. This is from memory, having been there, then I am drawing at night.

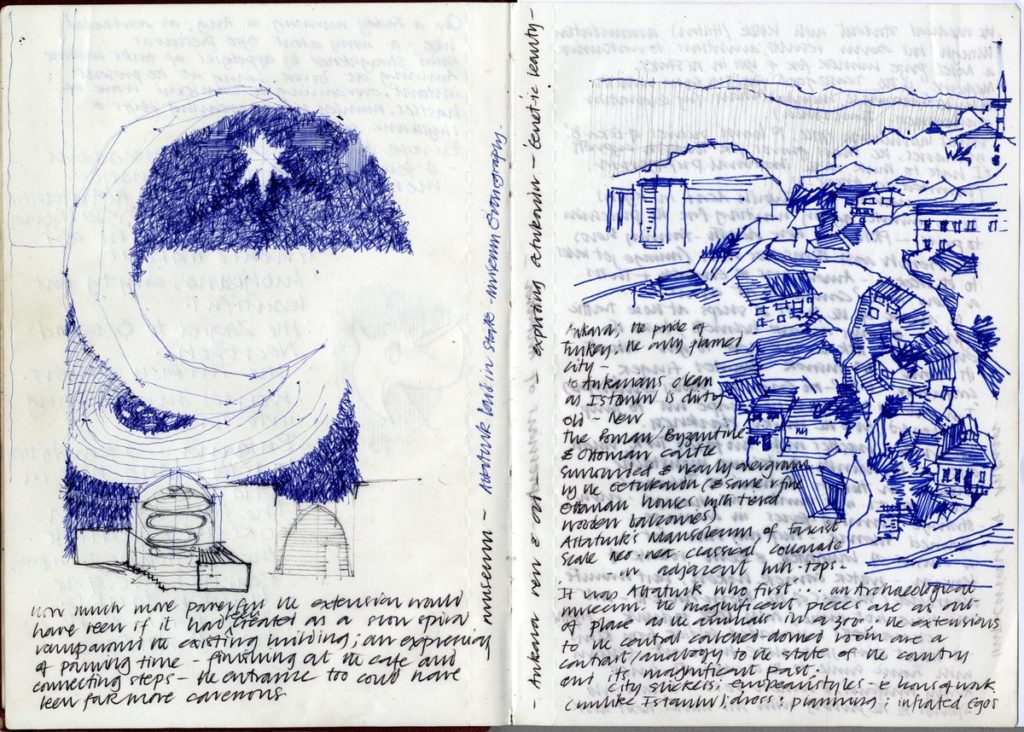

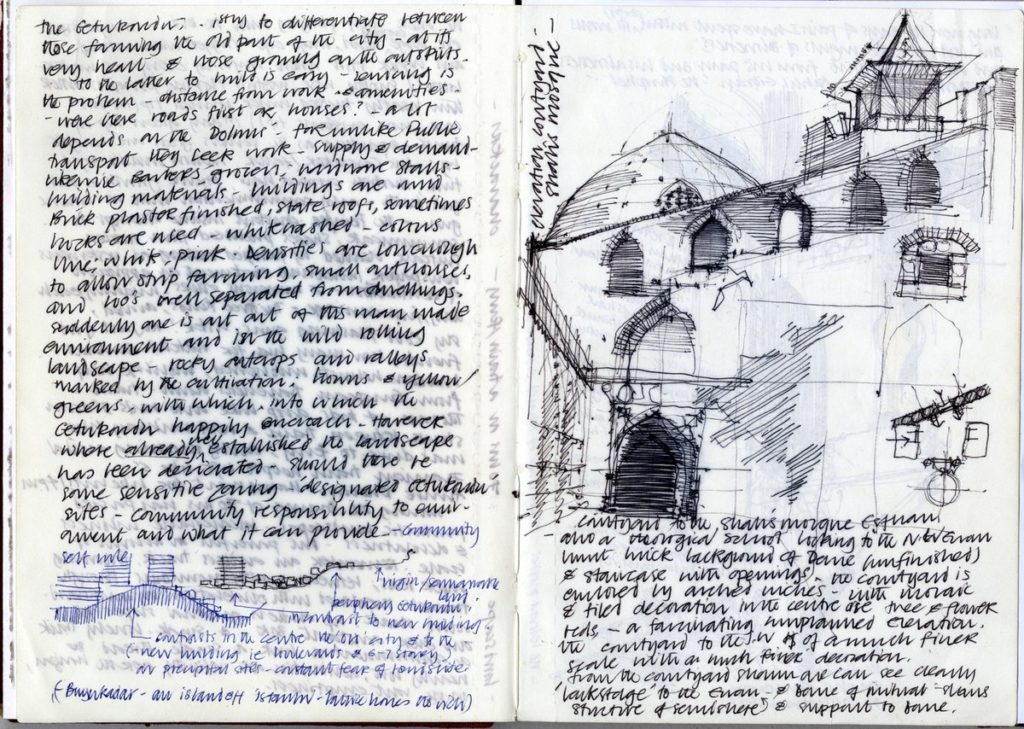

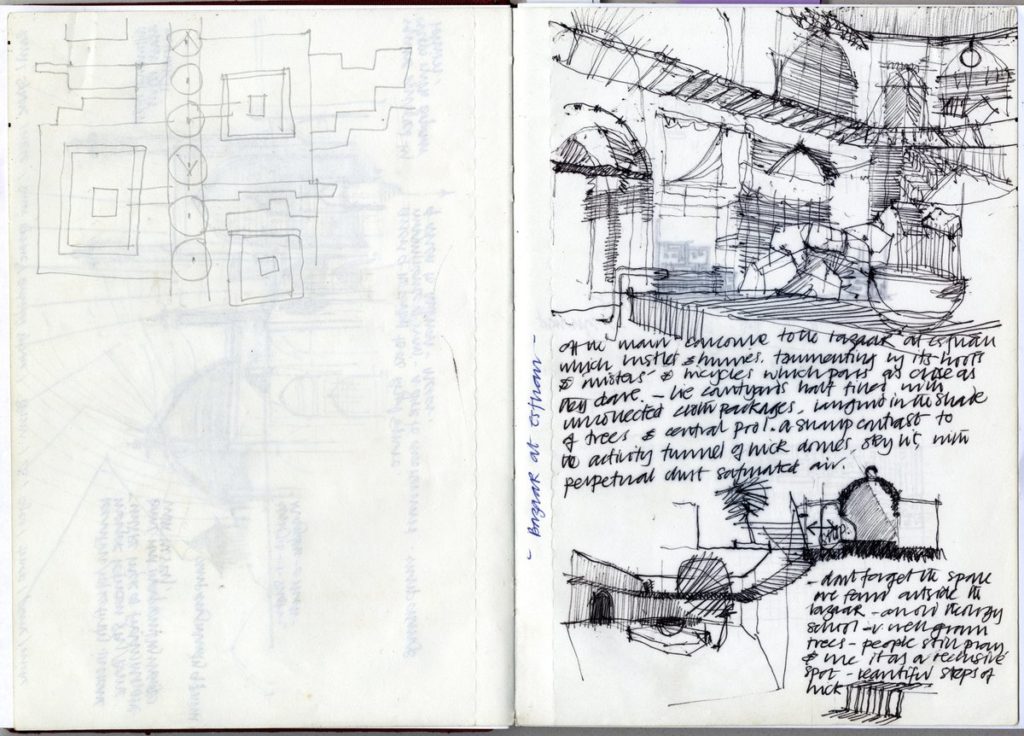

On the lower right (check) is a reflective description of the Gecekondu settlements in both their urban and more rural setting – quite a lot of thinking about this tension between formal and informal settlements, in India and indeed Kuwait. The, on the right is first encounter with Iranian architecture – an epic discovery – and the urban planning at Isfahan. On the next page, with blue ink, the sort of world of calligraphic colour and ceramics; then into the bazaar. This plan in pencil on the left – there is a central spine of domes with lateral openings into courtyards – it is a beautiful ordering device that runs like a spine through the city. The bazaar, this drawing, is an on-the-spot, analytic drawing.

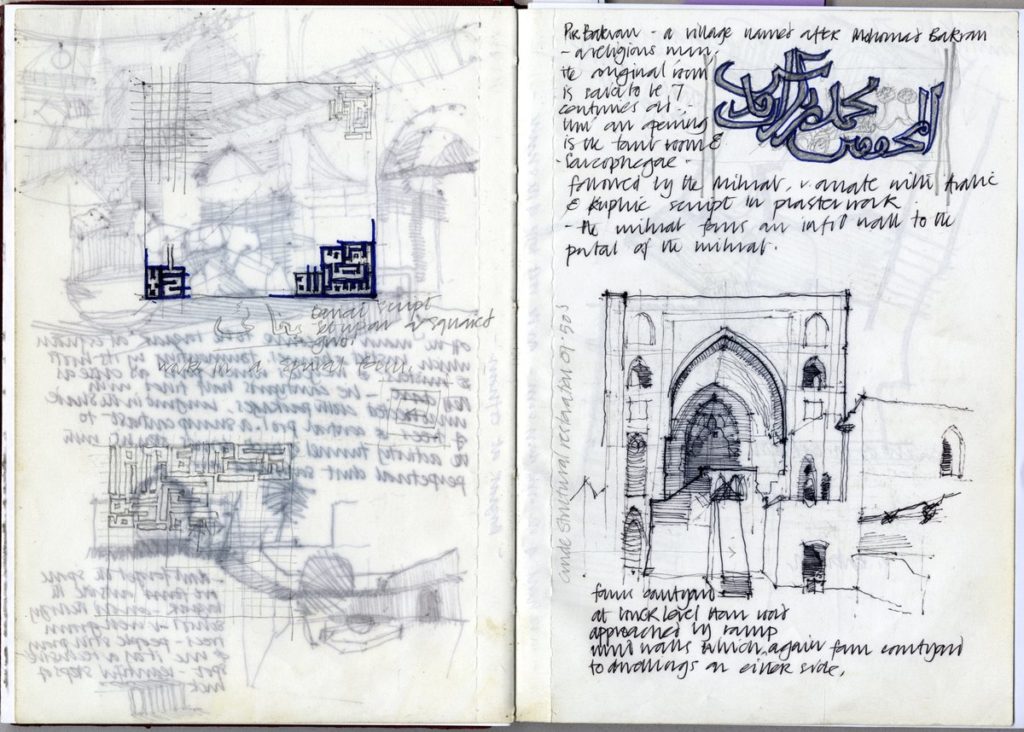

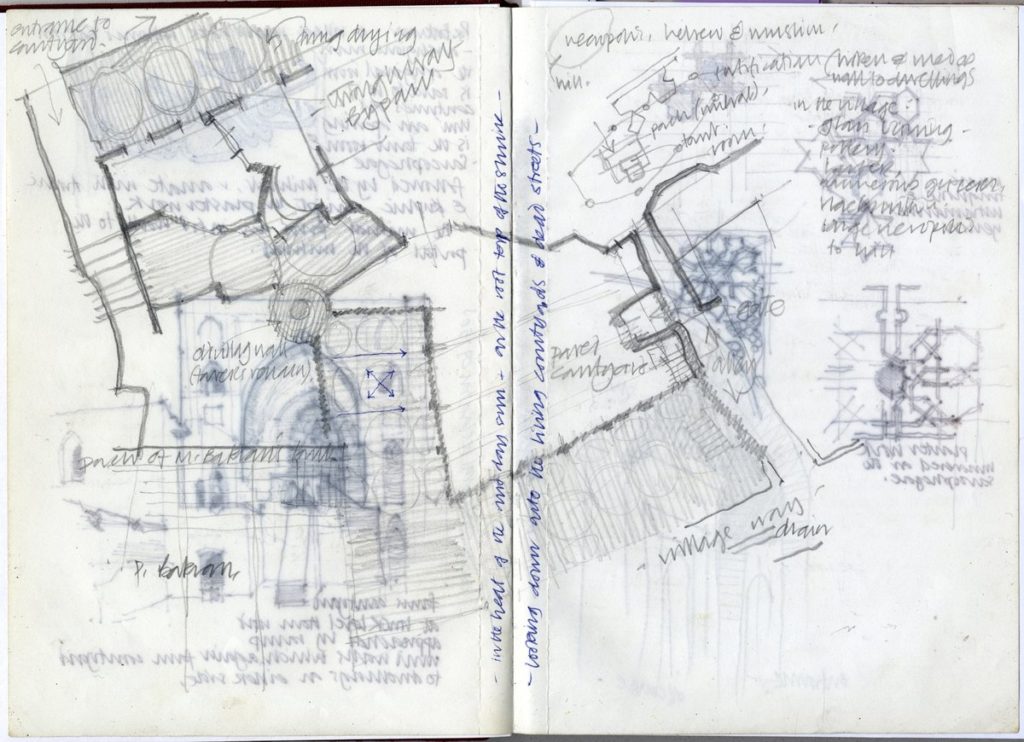

Then this is definitely there, the discovery of the Mausoleum of Pir Bakram. There is a lot of traveling going on here. Backwards and forwards. I am transcribing some observations about the script and threshold. These first dashes of the book reflect a rapid passage south with my then girlfriend Sue Francis. We travelled the first month together – driving out together on the motorcycle – then our paths diverged as she needed to return to start her diploma at the Architectural Association. I had to get her onto the plane back, after which I caught up with Andy Thorne with whom I spent the rest of the year.

This is Naqsh-e Rustam – at the time of the Persepolis conference, probably noted here – the necropolis twelve kilometres from Persepolis and perhaps the most awe-inspiring in the world. Alexander the Great took his revenge and burnt Persepolis whose polished black basalt still bears the marks of his laying waste.

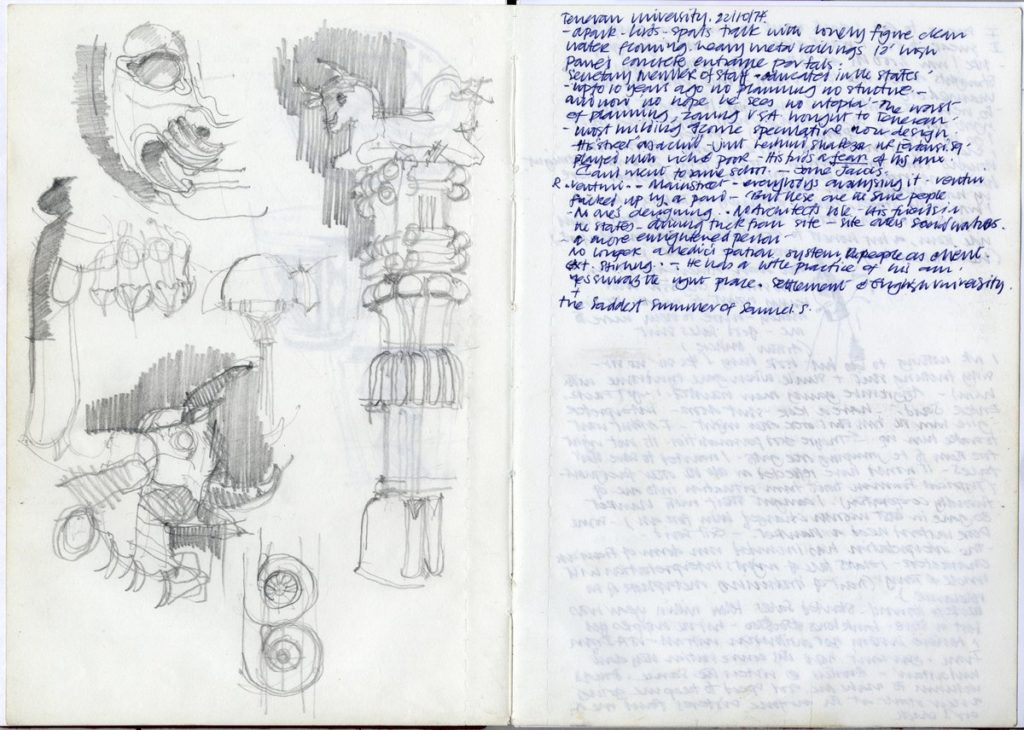

The conference – the Second International Conference of Architects – was in The Tent City, just outside Persepolis and erected by The Shah to celebrate the 2,500 anniversary of the founding of the Achaemenid kingdom, continuity of which he claimed. Khomeini, by the way, called it the ‘Devil’s Festival’. But we found ourselves amongst the architectural great and good: Derek Walker, Ungers, Nadir Adalan, Hassan Fathy, James Stirling, Candelas, Sert, and then Moshe Safdie, Paolo Soleri and Buckminster Fuller, all approachable at the bar and happy to share the debate with two young architectural refugees. The congress was an attempt to formulate a declaration for an international code of ‘human habitat’.

Andy and I about to embark on our surveying of nomadic settlements found it surreal. I had left England with £150 pounds in my pocket, and that lasted a year, in addition to my teaching in Tehran, giving blood in Kuwait for which they paid a small fortune, and receiving a small salary from the Kuwaiti Housing Authority.

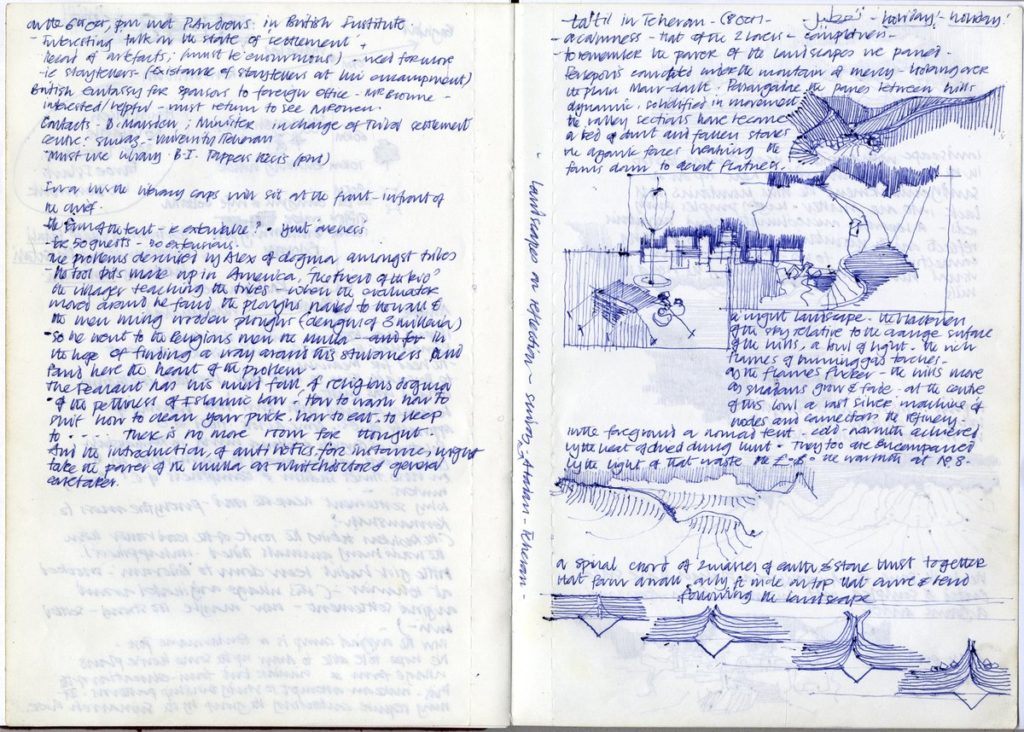

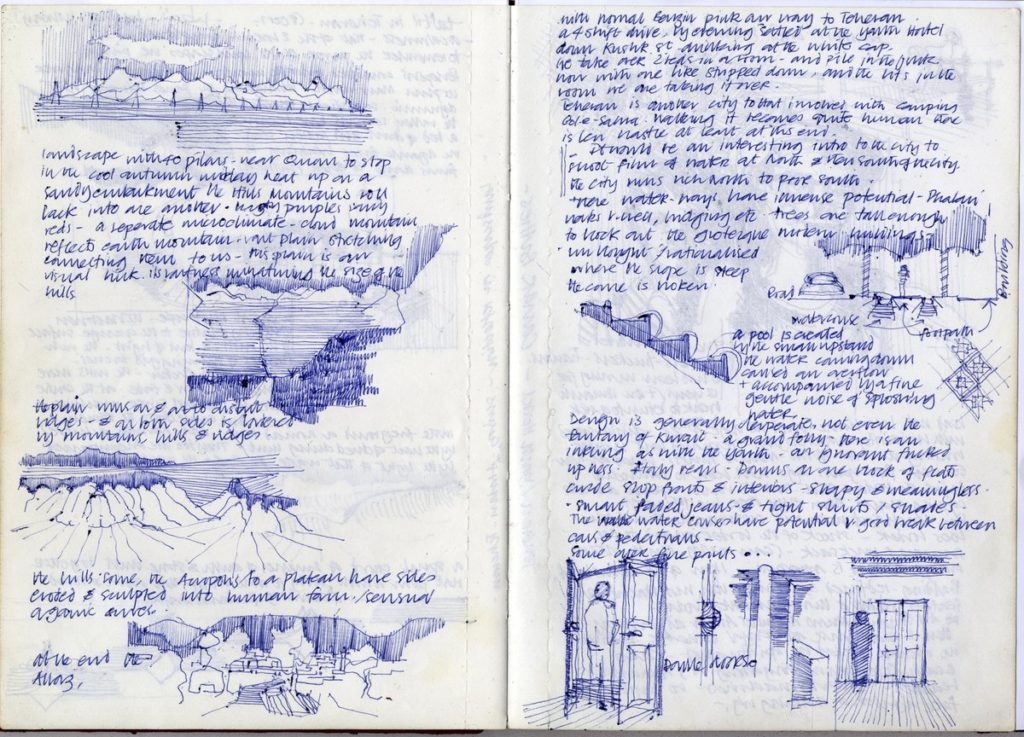

Then this is about the settlements and incredible forms of the Iranian landscape, well above sea level. It is a plateau which runs down and has a tremendously variable climate, from Tehran in the north with the Alborz mountain range through which you go to suddenly find yourself in the Caspian. The north facing slopes of the Alborz mountains create a landscape reminscient of Scotland.

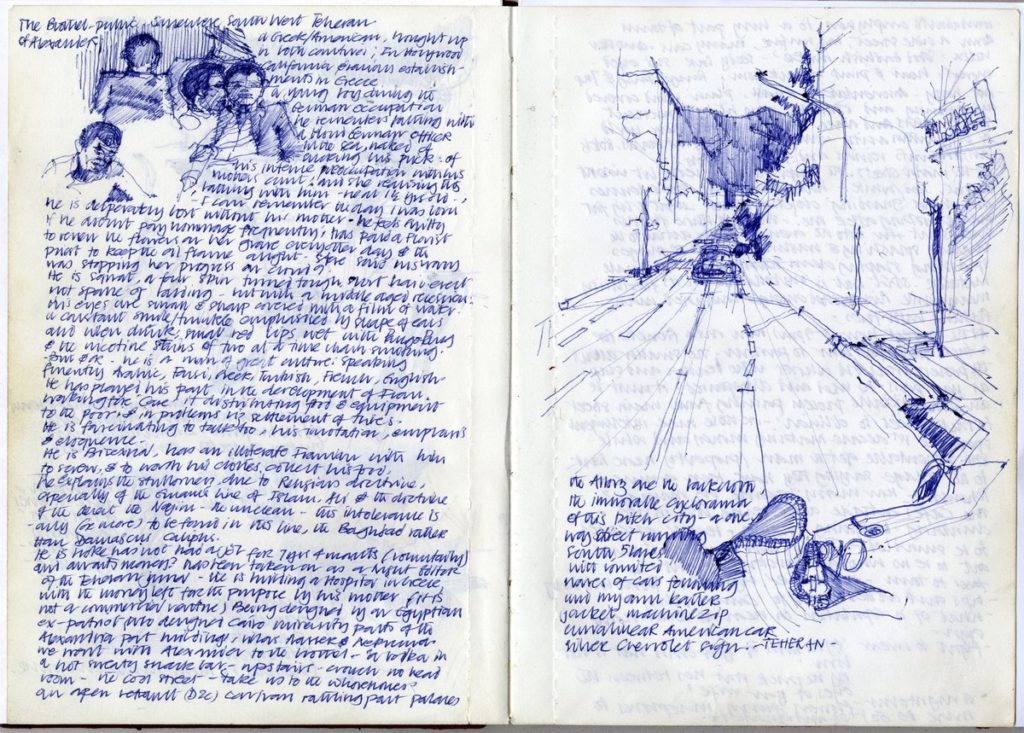

And this reflects the structure of Tehran. It is one of those cities where the rich live in the north, on the slopes, and the water goes from clear to foul as it flows downhill in open waterways, south to the market districts – a description of social hierarchy, of bubbling resentment of the Pahlavi dynasty that had such a stranglehold on life. One felt the hostility and surveillance that one was living in.

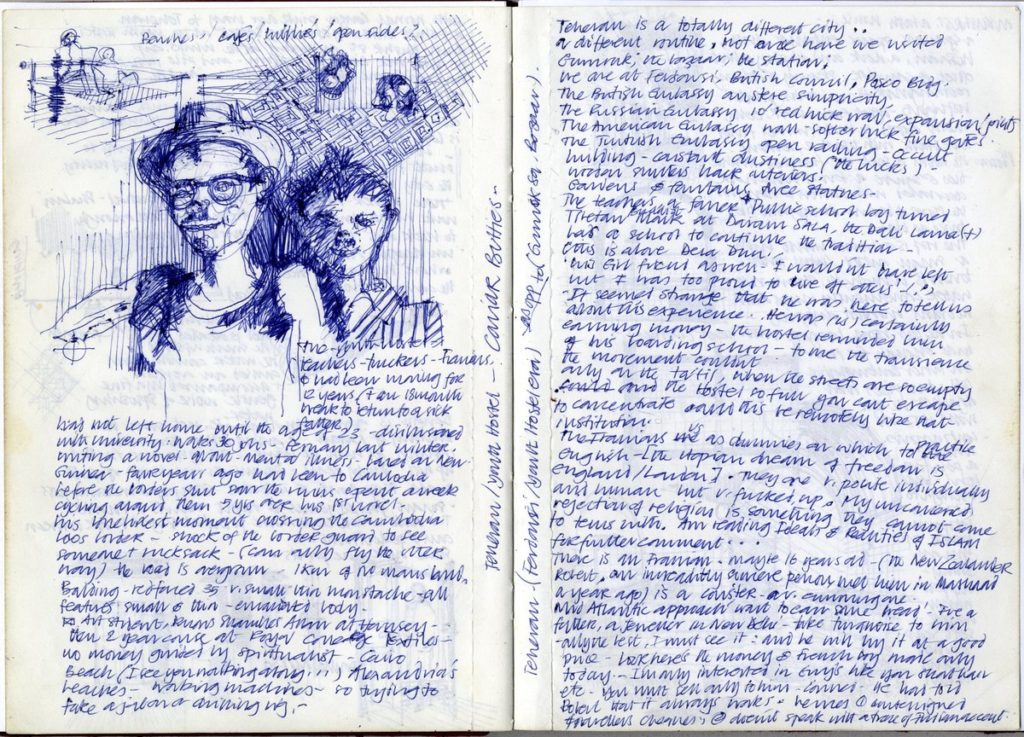

This is Steven Gatley. He had studied textile design at the Royal College of Art, had come hot footing from Egypt, moving through Tehran eastwards. We met at the hostel, in the middle of the strange world of a crumbling dynasty. At some point, after meeting Steven, speaking of the inspiration of the Royal College and his time there, I ended up coming back, following his steps of a foundation year at Hornsey College of Art and going to the Royal College to do architecture – then called Environmental Design.

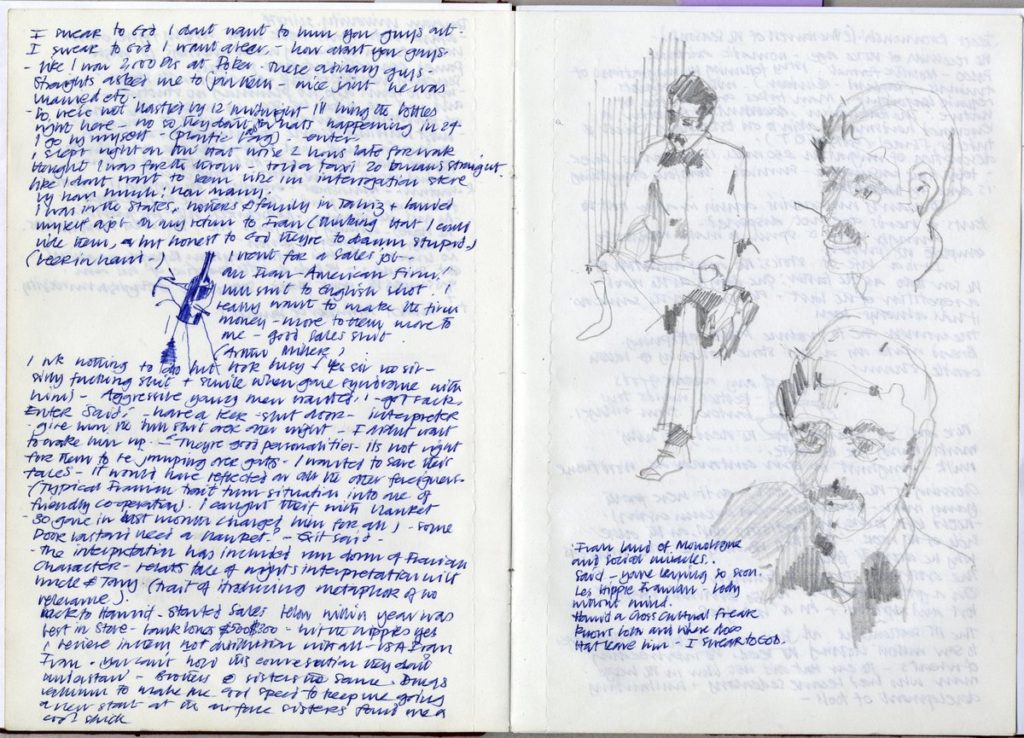

So these sketchbooks also reflect this period of personal uncertainty.

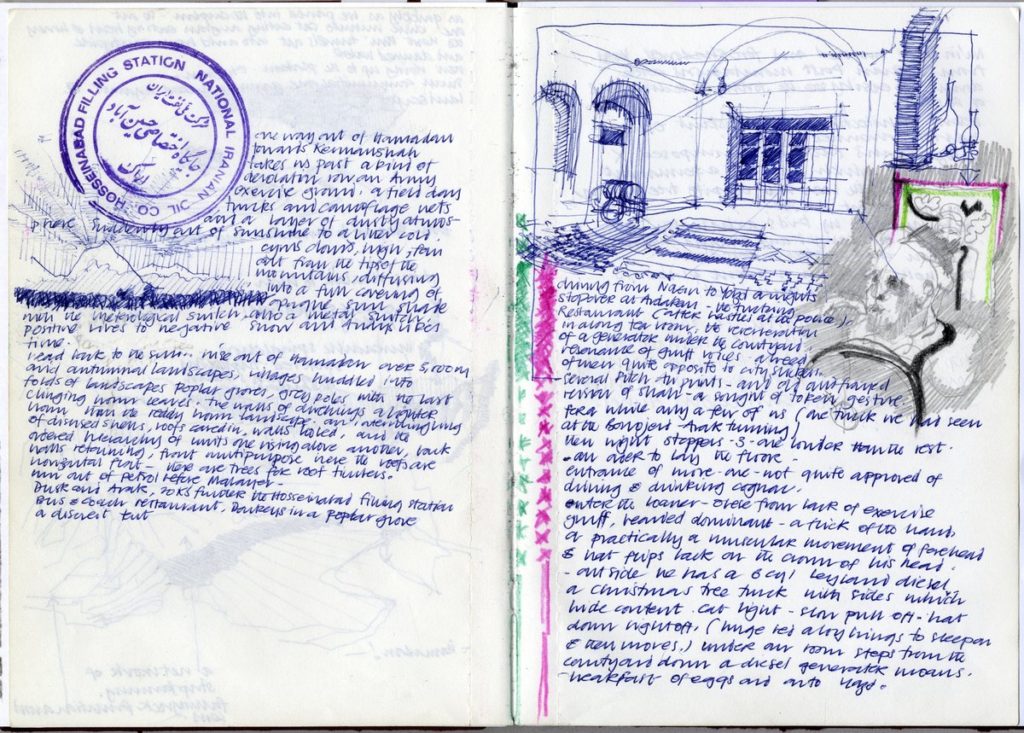

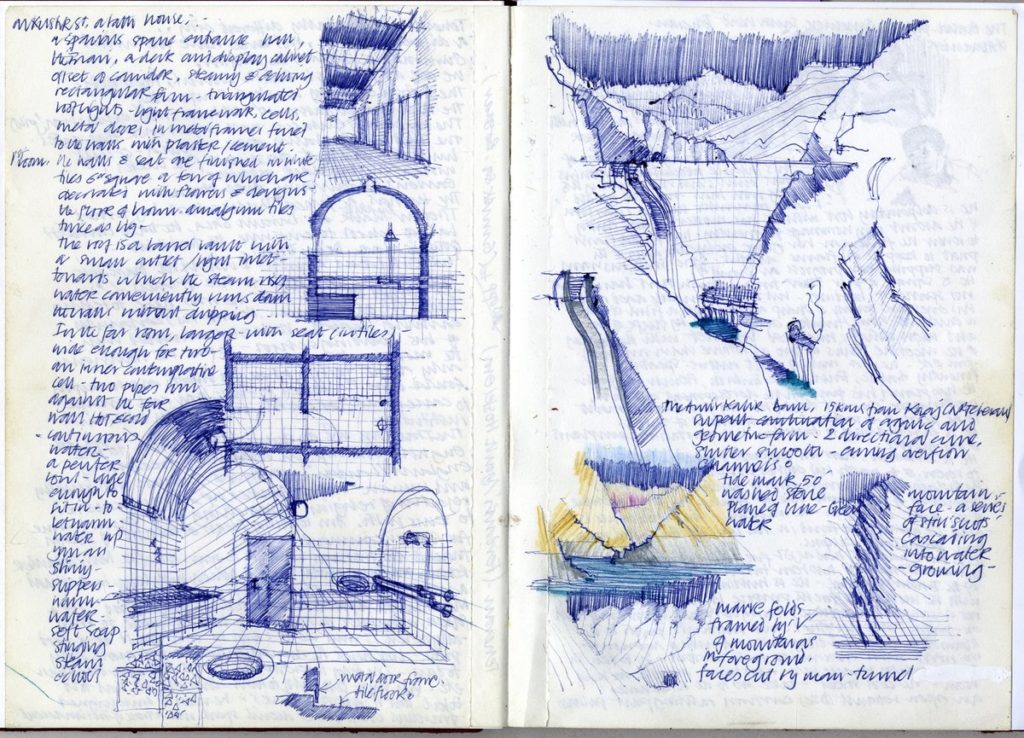

Here we come to the world of ablutions: the hostel did not have showers so one went round the corner to a bathhouse. There was a corridor with two interconnecting rooms, there was a bowl and barrel vaulted ceiling with skylights so that the condensation ran down the tiled walls. This was reconstructed after the event. It was very powerful in a way, just as a memory as well as a release from the hostel.

On the right a dam above Tehran in the Alborz – majestic pieces in the landscape.

Then to the underbelly of Tehran, this Greek, Egyptian – touching low life, going to the brothel which I think was known as the New City. A gridded quarter behind walls – it was like the water – there was a main street, and then a tragic sense of entrapment from youth to age. I imagine it was erased after the revolution. Then the mesmerising artefacts of the museum and a few pages dedicated to the Achaemenidian world, ceramics, fragments from Persepolis with a collection of delicate jewelry.

More of Tehran and more of dereliction, of certain figures hanging out in the hostel with a strong political agenda. This is one of them. He was a rather interesting man running through to the nomadic world, where you start to get in touch with that, which was the real purpose of the visit.

It is not just a sketchbook related to the nomadic world, but really a notebook. It is like a diary, not solely a diary but in it, there are references to literature, the people, the political situation. When one reads through, one gets a sense of this explosive ferment that is going on; one is not in there in a position of responsibility. We were not being treated like research workers. We got a research visa but later on, and reluctantly. The sketchbook also takes us into the world of the artefacts of the nomadic world. You have a sense of the topography of the country.

The moment of passing from the south side of the Alborz to the shadowed north is as a strong a contrast as going from a bright exterior to an interior, from warm to sub-zero temperatures and a descent to an alpine or like environment of timbered buildings, wattle and daub set in coniferous woodland and then coastline of the Caspian sea strange in its isolation and attitude. After this we started our trip southwards to study the Qashquai settlement.