Forecast and Fantasy: Architecture without Borders 1960s to 1980s – Review

This carefully curated and beautifully displayed exhibition brings together 150 drawings with numerous publications and films to display a wave of rebellion and research by architects across the European continent, with a focus on the east, over three decades. The abundance of visionary thinking that followed the boom of post-war reconstruction is on show, with architects turning to the fantastic as well as the personal to push the boundaries of their discipline towards the metaphysical; for an understanding of the self and the world at large. The exhibition offers a true treasure trove of thinking and drawing. Unexpected parallels emerge across the continent and there are many surprises even for the more cultivated visitor.

The show brings household names known for the poetic exploration of architecture’s boundaries – Archigram, Superstudio or Brodsky & Utkin – together with several lesser known but equally inspiring practices. The breadth of the material on display speaks of the networks that existed through exhibitions, publications, and private contacts. Archigram and Casabella were widely read, but it does not mean that they were the sole initiators of innovation or arbiters of vision. On the contrary, the broader geographies that this exhibition maps show a more complex network of resonance, inspiration, and innovation. It shows how sources of ideas, such as new scientific innovation, outer space, play, and gamification of thinking, new anthropological interest in the primitive and the self, and new relationships to ecology as well as built heritage, were shared and explored across the continent.

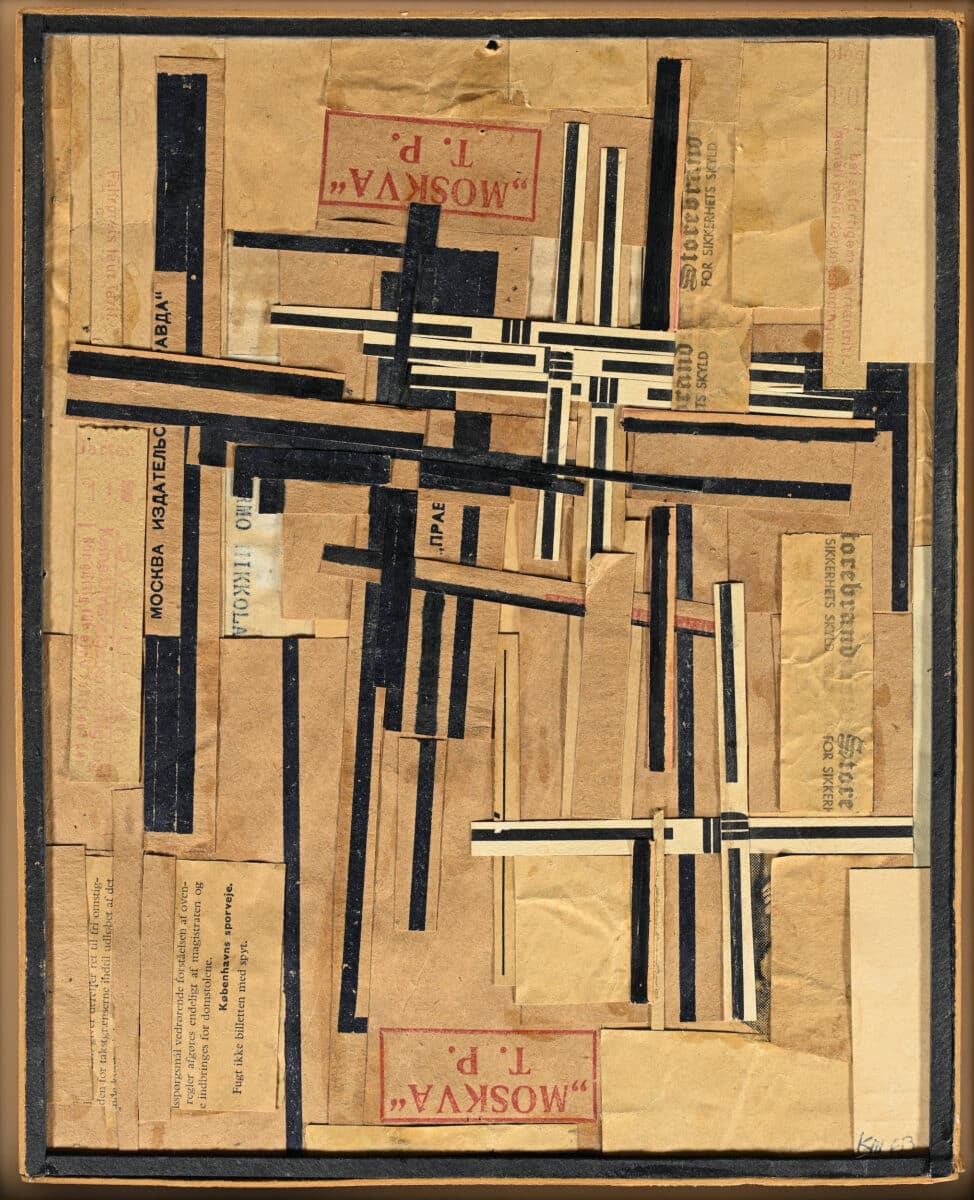

Weaving together and mixing work by architects from multiple countries through several well-articulated themes, the exhibition makes visible genealogies and practices that the biased perspective of narratives (that focus on Western European centres) easily misses. There are also many unexpected discoveries of the past, such as those seen in the well-known work of Brodsky & Utkin, or in the entirely unforeseen Suprematist collage by Finnish architect Kirmo Mikkola, which is dated 1963. This was years before Malevich became fashionable again in the architecture circles of the Southern and Western parts of the continent. A unique eye for the absurd, as well as a sense of irony and warmth is evident in many of the Eastern European works at the centre of this show.

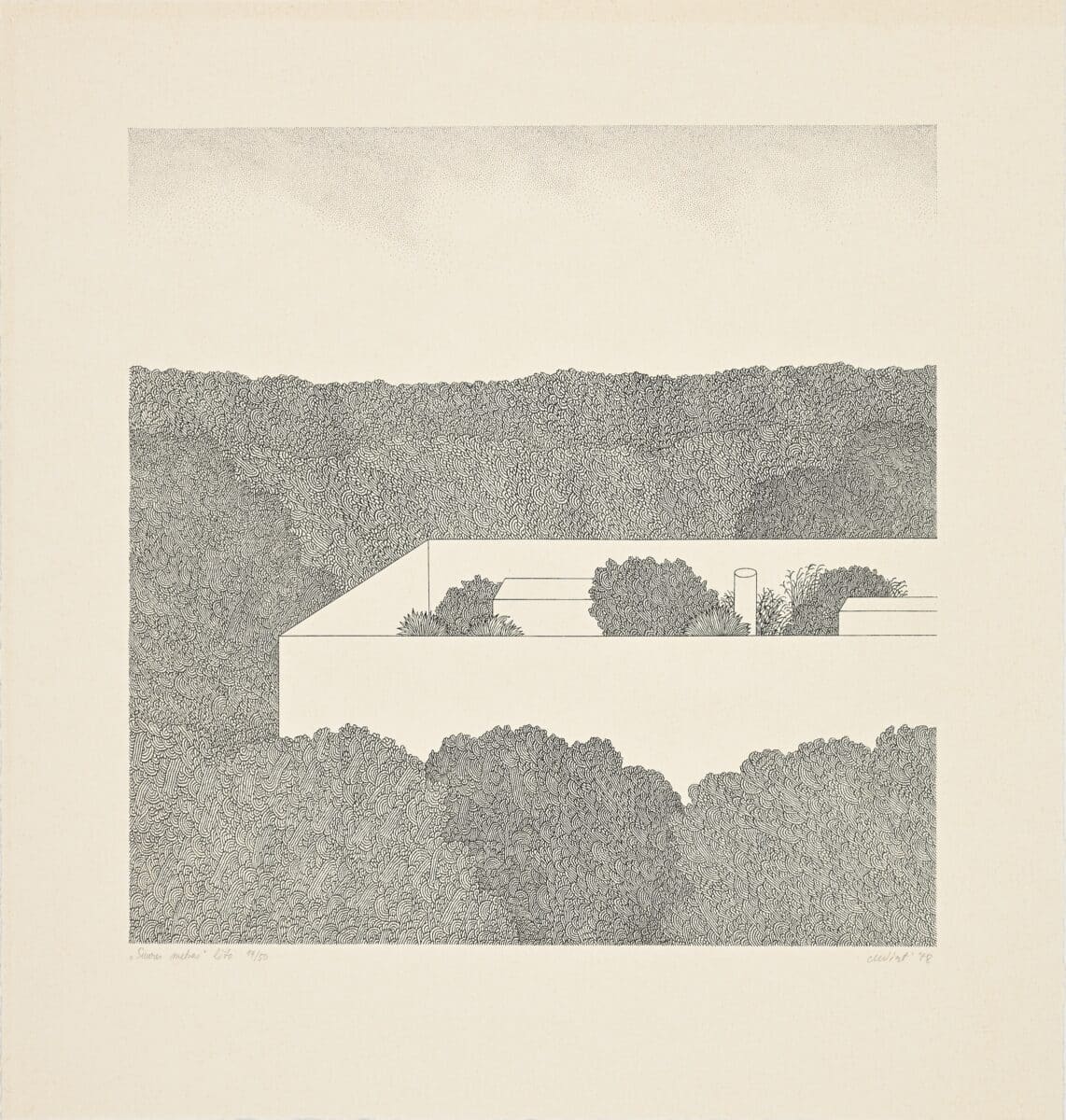

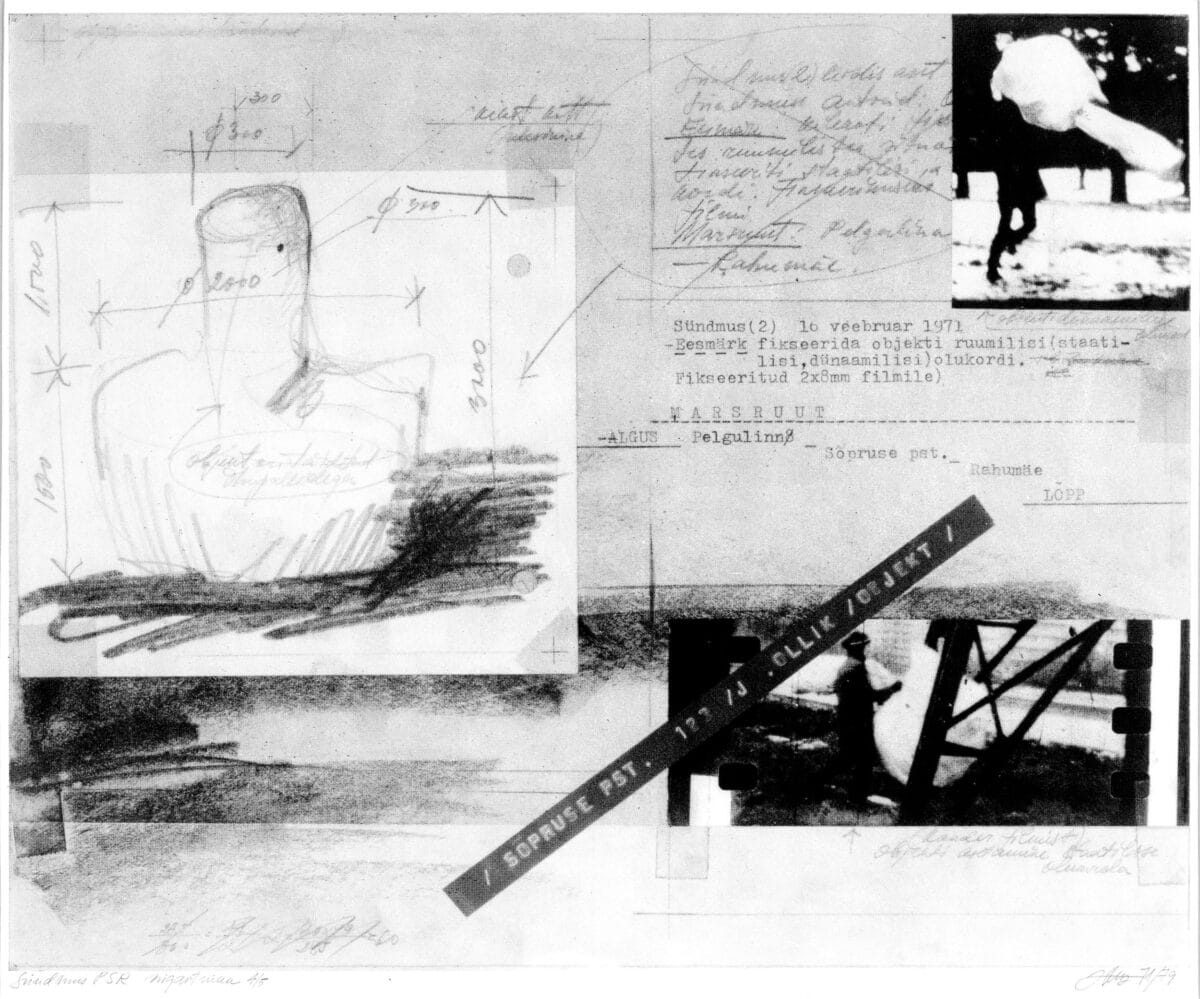

Some of the individual highlights are produced by Estonians (many of whom we know thanks to previous work by the same curators). An example is Mare Vint, whose at once serene and bewildering drawings of trees juxtaposed with various architectural structures seem as fresh as if done yesterday. Another is Jüri Okas, who turns architecture into performance art deserving of a place in any museum collection. Moreover, as with most of the work on show, both are inventive, inimitable, and ingenious in their use of their medium. For Okas, this is a multi-technique print and collage.

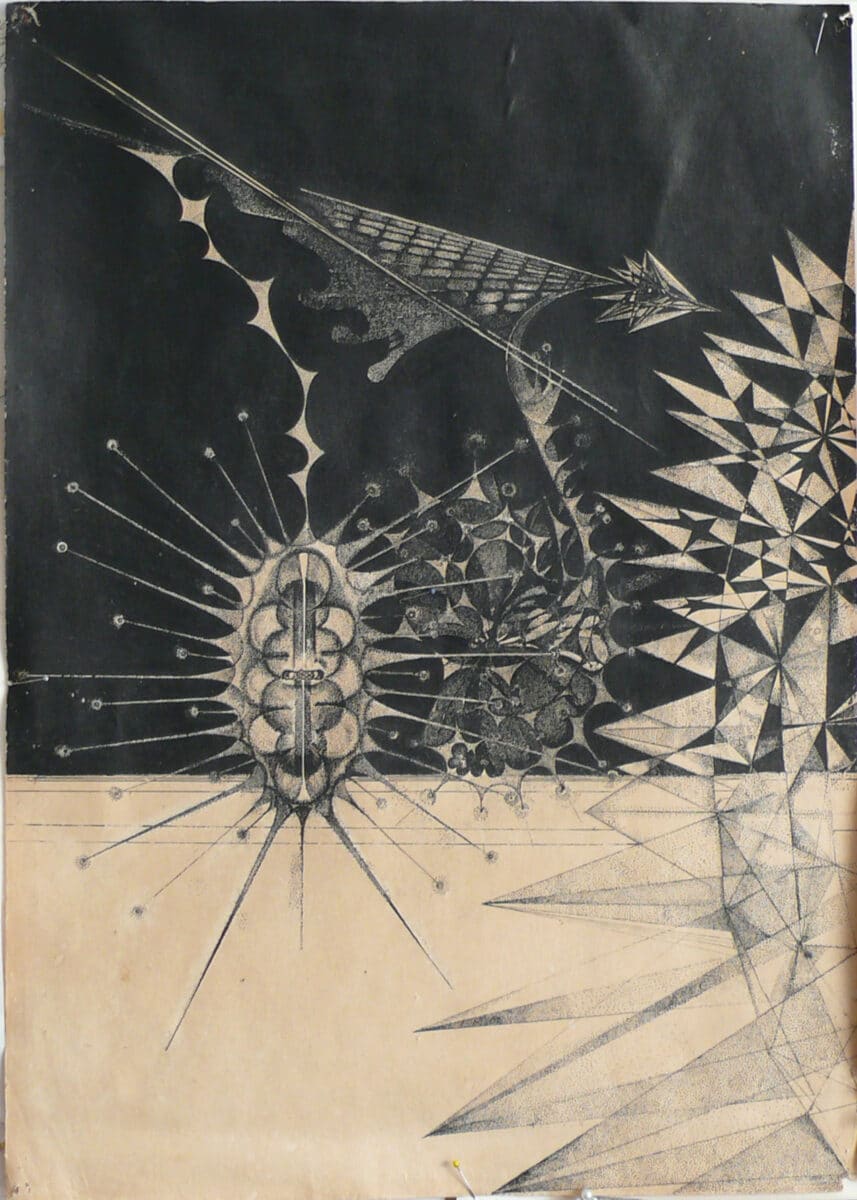

Notable others include the Slovakian Jozef Jankovič’s enigmatic buildings, such as the sculptor’s studio, where the anthropomorphic house becomes at once a medium for exploring the poetics of interior space, architecture’s capability for expressivity, and the limits of the entire art. It is a house that houses what a house can be, and what it can mean. Moreover, it is architecture as the art of the self – since we can only presume that the sculptor, and thus the anthropomorphic house too, is the author himself. Yet another moment of surprise and discovery is presented by the drawings of Galina Bitt, Natalia Prokuratova and the rest of the Moscow-based group Dvizheniia, which employ an array of drawing techniques to create diagrams of being at all scales, from daily domestic interaction to universal existence in space.

In all these cases the medium is inextricably linked with the message. Vint’s use of colour and compositions of simple, geometric architectural forms with nature make ambient worlds where architecture looks for its place in the world, not unlike Superstudio’s drawings for the project Un viaggio nelle ragioni della ragione that it stands next to. But Vint’s works have a quiet sense of wisdom and mystery compared to the more in-your-face poetics of the Florentine group. What both share though, is the constant play with conventions of drawings, whether it is Superstudio’s use of perspective or Vint’s enigmatic, meandering line. Seen closer, the soft labyrinths of serpentine line that constitutes the trees in her works transform the images in equal parts into meditations about the line itself, and evidence of the movement and labour that is behind it. Drawing here, appears as a meditative practice that can aspire to make sense of the world, or reinstate its mysteries.

For Jankovič too, drawing the house appears as the project itself: a testing of architecture as drawing as much as an exploration of architecture as space and form. In one drawing only – a perspectival section of the sculptor’s house – we see each of the elements drawn in a distinct manner of its own. The ground is washed in dark brown watercolour with uneven surface and colouring as in a 19th century geological drawing. The interior and ground surfaces are drafted in straight lines in black ink. The repetition, as well as the alternating strength of the line evoke the quality of that made by a burin. The simple shell structure that seamlessly continues to a cupola, which is shown in partial section, is depicted in bright translucent yellow, in what seems to be a soft pastel, whereas a cluster of cubic geometric forms that grow on top of the building are drawn with a bright red, medium-thick marker. The nested geometries and meanings of this house-as-a-self-portrait are formed by these nested geometries of drawing.

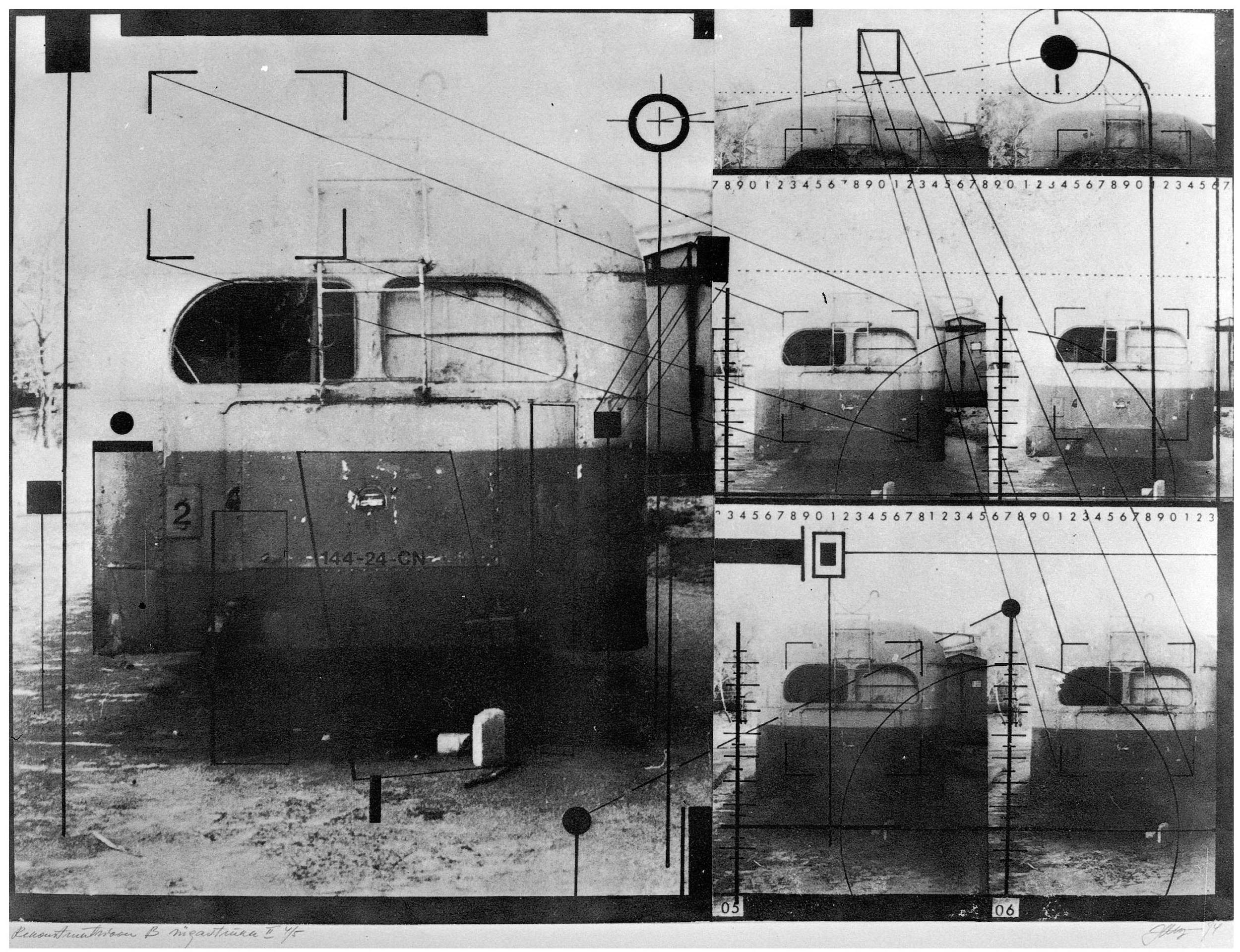

Okas’ way of dealing with the documentation of installations and performances offers another creative way of using drawing and printing techniques. He employs an array of techniques collaging photographs and film fragments. He draws over them and then reproduces them as one-off works, or as prints with runs of 2 or 3; apparently made by using a heliographic press to overexpose various stills from super 8 films on top of one another. Strong, speedily drawn lines across the enlarged and collaged images create a super-graphic that ties the fragments together and adds yet another layer of information.

Many of the drawings on show seek inspiration in their medium from a rich source of historic inspirations. Vint’s method of drawing her trees is one such example, as is Okas’ way of using antiquated techniques of reproduction to create originals for the documentation of an event in print. Some other techniques, such as Brodsky & Utkin’s use of etching, Totan Kuzembayev’s white-on-black drawings in the style of Ivan Leonidov, or Leonhard Lapin’s Suprematisms, are already iconic, but there are many more and less obvious cases in the show. These include drawings by Galina Bitt and Natalia Prokuratova. Their varied techniques often evoke 18th and 19th century scientific illustrations, whether through using tempera and ink to create images of lucent objects in dark space, or by composing their drawing as if seen through a microscope. Such riffing on conventions makes the medium of drawing itself work as powerful evidence of the curators’ thematic arguments about architecture’s vicinity to science and innovation. They also make an interesting parallel to another simultaneous exhibition at Tallinn’s Art Museum on the importance of art and drawing for 19th century scientific exploration of new realms, from botany and geology to human anatomy. Drawings such as those by Dvizhenie at the Museum of Architecture show how during 1960s to the 1980s it was architects who strove to claim their art as the one of making sense of new worlds.

The joy of discovery that the exhibition brings, and which its design effortlessly encourages, may serve to hide the question of why these specific works have been selected and others not. But the fact that it does so seems to prove the point. The intuitive constellations and connections that the curators make form a whole that conveys the richness of architecture’s pursuit, its rethinking of what it means to be human and live together. The show reveals how architecture aspired to be part of society during these decades. It also offers a fresh look at the geographies and historiographies of European post-war architecture. On my way home from the show, I was left wondering whether I had read the words ‘Modernism’ or ‘Post-Modernism’ anywhere in the abundant wall texts and labels. Perhaps I did, but they certainly were not the key labels through which the exhibition operated – something that seemed awfully refreshing.

Andres Kurg, Mari Laanemets ‘Forecast and Fantasy: Architecture Without Borders, 1960s to 1980s’ is on display at the Estonian Museum of Architecture, Tallin from 20th January to 30th April 2023.

Markus Lähteenmäki is a curator, editor and architectural historian, post-doc at the University of Helsinki and currently visiting Research Fellow at UCL Institute for Advanced Studies.

* * *

To celebrate the opening of Forecast and Fantasy, and to complement those images accompanying Markus Lähteenmäki’s review above, curator Andres Kurg has generously shared the following images, all of which are included in the exhibition.

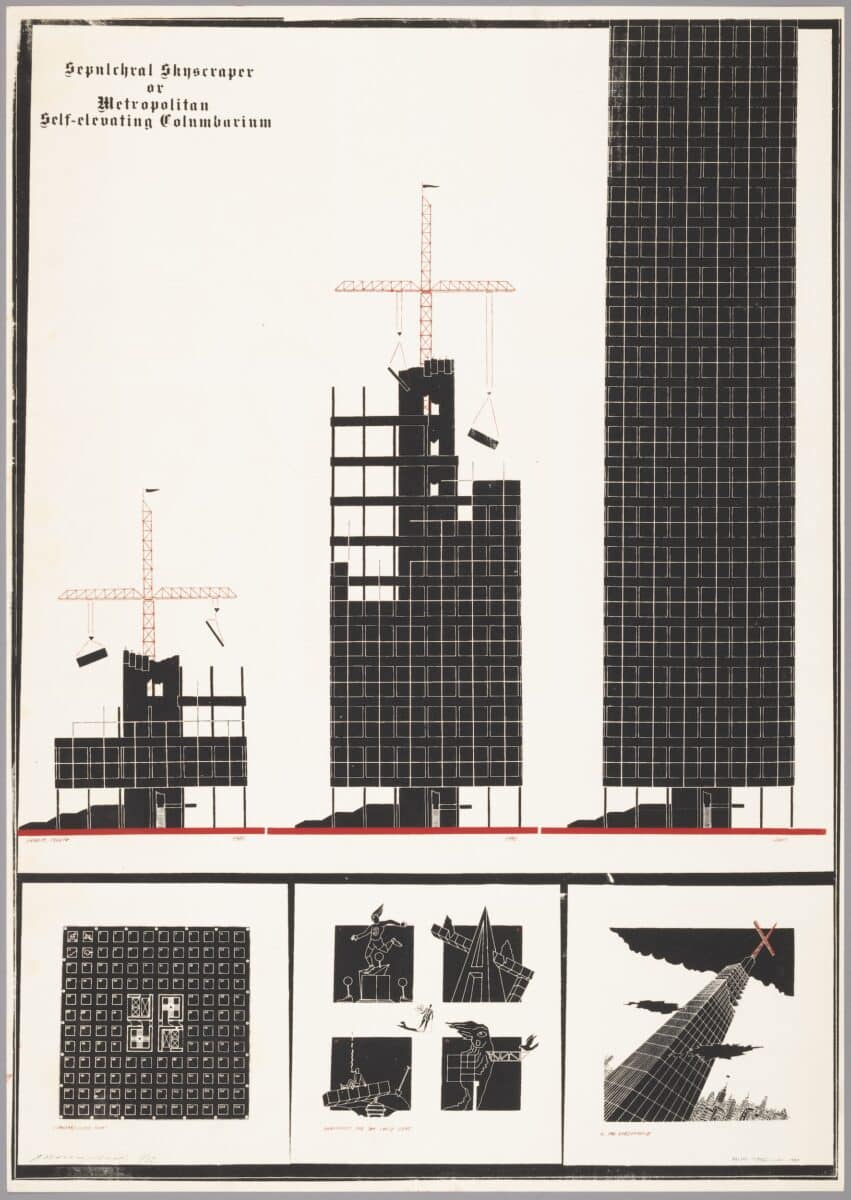

In order of appearance: (1) Gábor Bachman, Miklós Haraszti, György Konrád, László Rajk. Bulwark of Resistance: Striker’s House, 1985. Entry for Japan Architect competition, Honorary Mention. Ink on tracing paper. Private collection; (2) DNA (Igor Drěvíkovský, Jan Hrubý, Martin Šarbot and David Vávra). Regeneration of Praha Jižní Město housing area, 1986. Display board for exhibition Urbanita‘86. Mixed media, cardboard. Private collection; (3) Kirmo Mikkola. Good-bye, Futurology! (Tatlin’s Nighttime Walk), 1970. Collage, cardboard. Private collection; (4) Vilen Künnapu, Ain Padrik, Lennart Meri. Sketch for the Rovaniemi Arctic Centre competition entry Silverwhite, 1984. Pencil and coloured pencil on tracing paper. Private collection; (5) Lev Nussberg (Dvizhenie). Cross-section of a Bion-Kinetic Environment (IBKS), 1968. Ink on paper. Private collection; (6) NER, Sergey Telyatnikov. View of the New Element of Settlement. Preparatory sketch for the exhibition at Osaka World Expo, 1970. Private collection; (7) Jüri Okas. Happening PSR, 1971/79. Intaglio. Private collection; (8) Jüri Okas. Reconstruction LO, 1974. Intaglio. Private collection; (9) Jüri Okas. Reconstruction S, 1974. Intaglio. Private collection; (10) László Rajk. Development (The Heritage of Le Corbusier). 5 Projects, 1977. Black and white photographs, architectural drawings. Sárospatak Art Gallery; (11) László Rajk. Development (The Heritage of Le Corbusier). 5 Projects, 1977. Black and white photographs, architectural drawings. Sárospatak Art Gallery; (12) László Rajk. Interruption. (Monument to ÁÉV no 43 and FŐBER). 5 Projects, 1977. Must-valged fotod, arhitektuurijoonised. Sárospataki kunstigalerii; (13) Sirje Runge, Solar System II, 1976. Graphite, coloured pencil, gouache on paper. Private collection; (14) Mare Vint. Brick Wall, 1977. Lithography. Private collection; (15) Mare Vint. Greenhouses in the snow, 1979. Lithography. Private collection; (16) Mare Vint. Passage to the underground, 1978. Lithography. Private collection.