Superstudio’s Collage Chest: A Chance Machine

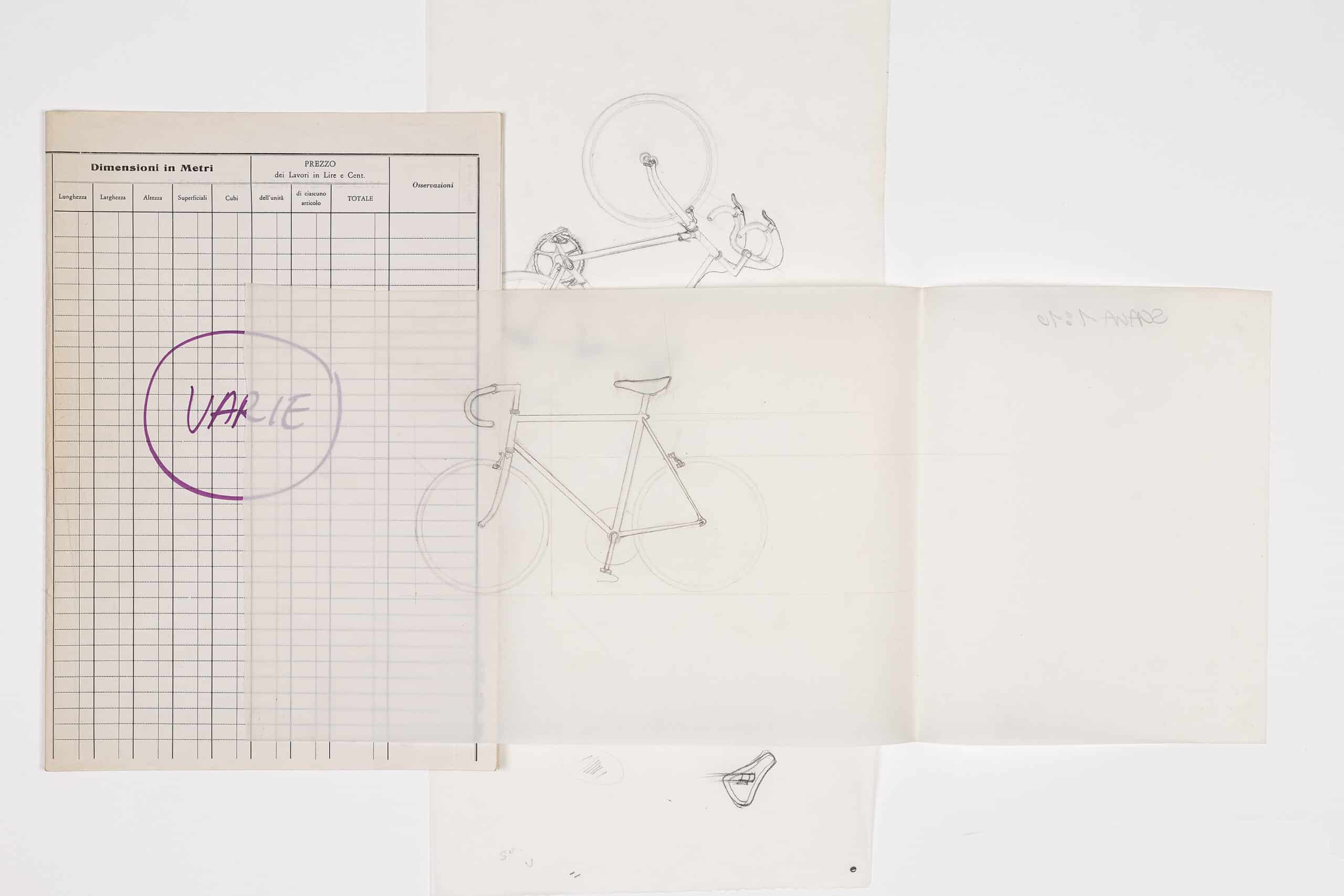

In 1968 Adolfo Natalini’s partner, Frances Brunton, returned to Florence from London with their newborn daughter and a small wooden chest with five drawers. On three sides of the chest, Natalini hand painted sky-blue flowers on an orange background. The chest of drawers was then taken to the Superstudio-studio in Piazza di Bellosguardo and used from 1969 until 1973 to store the source material for Superstudio’s famous collages: photographs, newspapers and ripped-out magazine pages. Only a select few images were given the privilege of entering the chest, and only a fraction of those were cut-out and collaged. The chest has now been untouched for almost 50 years and currently lives in the Drawing Matter collection. The images that remain in the chest today were never chosen to be in a Superstudio composition; they were selected to enter the chest but not to leave.

The content of the chest is divided by subject matter. The drawers are labelled from top to bottom as follows: Machines; People, Cars and Aeroplanes; Landscapes; Architecture; Art. Natalini explained that the categorisation was by no means scientific – why did they keep cars and aeroplanes with people rather than machines? (which, in fact, is the drawer that holds most of the car and aeroplane photos) – but worked well for the needs of Superstudio. This imperfect organisation enables accidental discoveries and unexpected connections. You cannot simply open the drawer to find what you are looking for; instead, you have to pull the whole drawer out from its runners and get lost within the disorder. Here, you will likely find an image that barely corresponds to the label on the drawer, or, perhaps, you will recognise an unusual relationship between two seemingly unrelated images. Do not be fooled by the labels, the collage chest is a chance machine.

Had there been six drawers instead of five, had the drawers been shaped or ordered differently, or had there been a lock on the drawer, Superstudio’s collages would have certainly turned out differently. Even the shuffling of images with each opening and closing of the drawers must have had a certain influence over the final product. A different chest would have led collages to be composed of different images. The chest’s influence was probably even more fundamental because a single image could serve as a catalyst for the entire concept of a collage. Therefore, the chest was not only a chance machine for curation but also a random generator of ideas. It was as much a collaborator as it was storage.

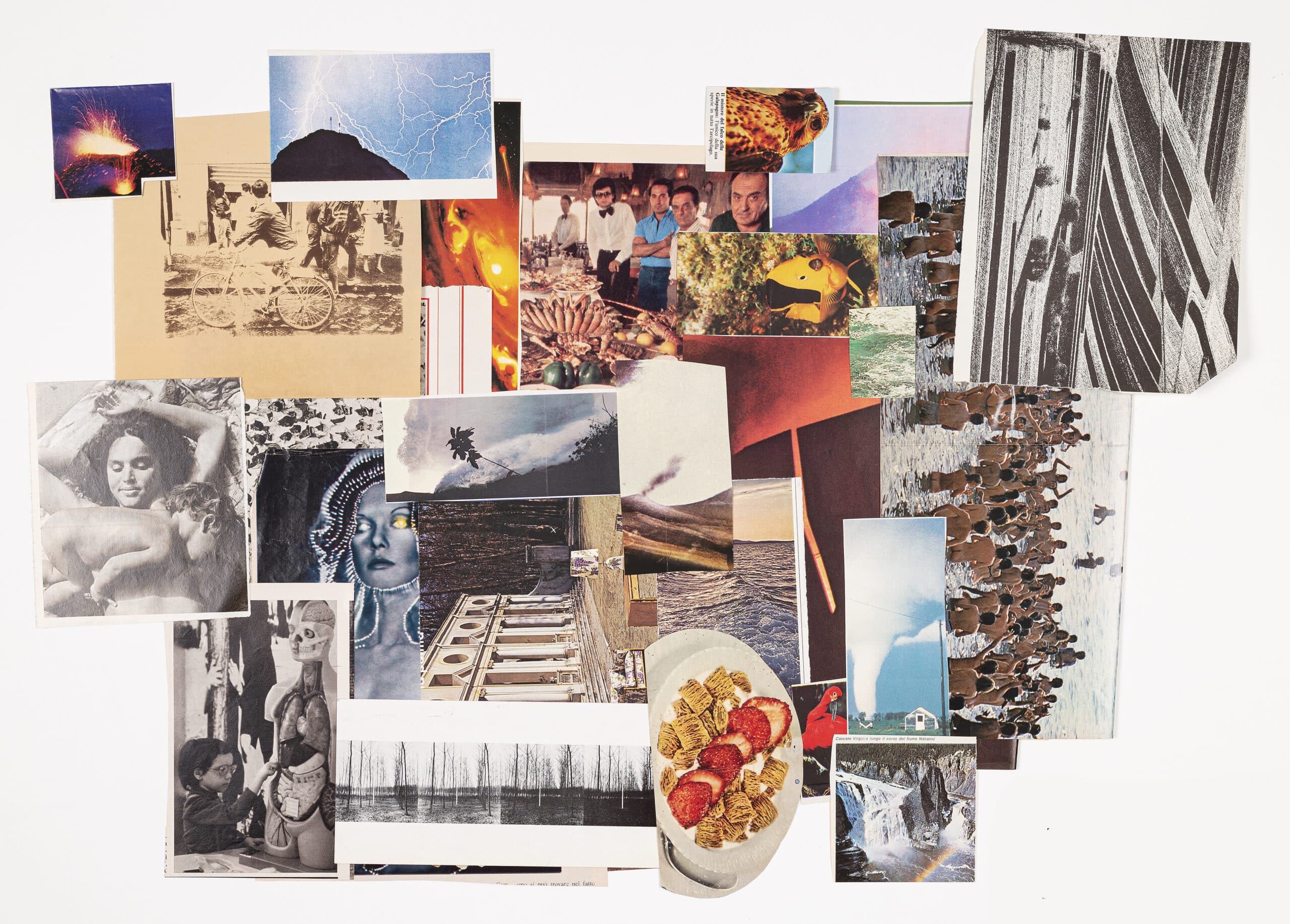

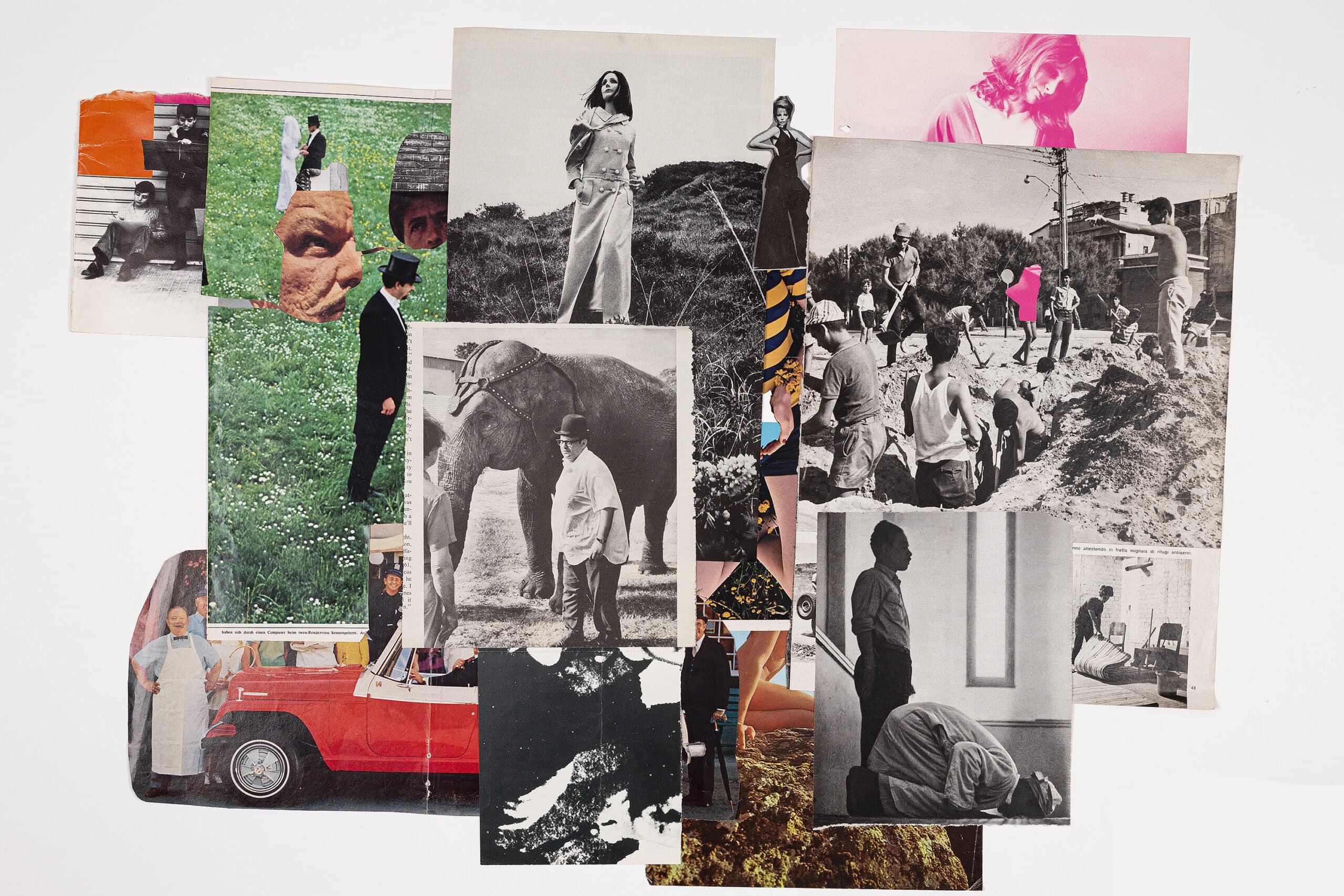

The images in the collage chest are a distillation of Superstudio’s world. Accumulated from popular media outlets, photojournalists and advertisers, no aspect of life is left out: the obscure and the ubiquitous; the wholesome and the raunchy; the extraordinary and the mundane all found a home in the chest. If the archeologists from a far future or some extraterrestrial species discovered this chest, they would get a comprehensive though highly distorted sense of how people lived. What conclusions would they draw from the unexpected themes that span across the drawers: furniture sets photographed outdoors, extravagant family meals, absurd fashion, water, naked single parents with their babies, red lasers, and group photographs in which each person represents a different occupation or culture in society.

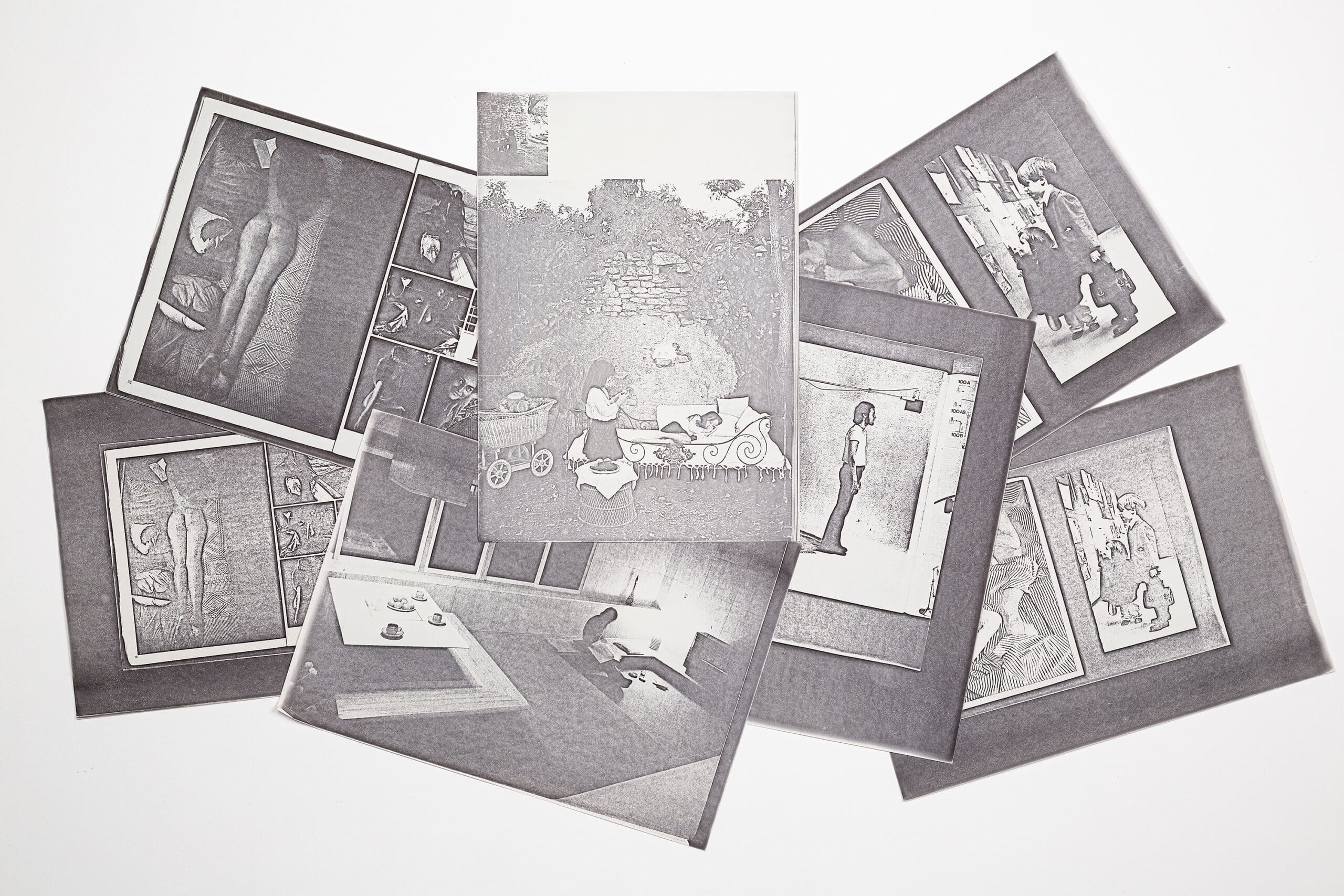

In reality, the contents of the chest tell us a lot more about Superstudio than it does about the world. To pull out a drawer is to peek into the minds behind the collages. Though it is hard to guess why most of the images were selected, some of them directly correspond to the group’s ideas, such as those depicting the bourgeois lifestyle, hippies, grids and expansive homogeneous landscapes, both natural and built. [1] Then there are the images that were tampered with; evidence of the human hand that reveals different techniques that the studio used. These are the images that were trimmed, torn, traced, or taped. There are also some washed-out photocopied images and photocopies of the photocopies. Perhaps most compelling are the squares of trace taped next to images in order to extend orthogonals and find the vanishing point(s) and horizon line. The type of image manipulation can indicate different levels of interest in the image or different plans for what to do with it.

The collage chest today is an instrument of the past, but it has also taken on a new life as an interactive art object. Looking through its drawers was once a step in an image-making process, but it is now an end in itself. When one flips through the material, an unintentional montage unfolds through time and generates new stories connecting the images. It is chance filmmaking, not unlike the techniques employed by the Dadaists or John Cage. When one stops flipping, a happenstance collage is often sprawled out on the table. The contingent layering of clippings suggests foregrounds and backgrounds. Strange theatrical scenarios come to life, often with advertisements or large faces as their sets. The cut-out voids are filled with the image behind them: a gun in the shape of a tree, a jumping dancer in the shape of someone standing still. The images that remain in the chest will never assist in representing The Continuous Monument, 12 Ideal Cities, or Fundamental Acts, but they ultimately participate in a different kind of collage that is participatory, constantly changing, and ripe for imaginative interpretation.

Notes

- ‘Superstudio’s choice to incorporate images of hippies into their photomontages of a proposed democratic network was anything but arbitrary and reveals a thorough understanding of the hippie’s own conscious strategy of refusal.’ Ross K. Elfline, ‘Superstudio and the “Refusal to Work”’, Design and Culture 8, no.1 (2016), pp.55–77.