Giuliano Fiorenzoli: Because of Seeing Architecture (2023) – Review

In 1977, two years into the city’s fiscal crisis, I moved to New York City—a young architecture student, ready to take in everything the metropolis had to offer. What I found was a city scarred by garbage strikes, the blackout, and a serial killer calling himself the Son of Sam. ‘Ford to City: Drop Dead’ had been the President’s response to New York’s plea for debt relief, and it looked as if the city might do just that.

The city’s crisis was the local symptom of a larger recession, worsened by decades of overspending and poor management, but whatever the cause, there was little work for architects, particularly those operating outside the mainstream. Michael Graves was teaching, working on kitchen additions, and supplementing his income by selling drawings. At the Max Protetch Gallery on 57th Street, alongside work by Graves, I saw exhibitions of drawings by Aldo Rossi, John Hejduk, Massimo Scolari, Leon Krier and later, Zaha Hadid and Daniel Libeskind.[1] Bernard Tschumi showed the Manhattan Transcripts downtown at Artist’s Space, and in 1978, following the publication of Delirious New York, the exhibition ‘OMA: The Sparkling Metropolis’ opened at the Guggenheim. I had seen Archigram’s drawings at the Art Net in London and projects by Superstudio and Archizoom in the MoMA exhibition ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape.’ In the history of architecture courses taught by Tony Vidler at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, I was introduced to the work of Boullée and Ledoux, reinforcing the idea that a drawn project could have historical consequences equal to that of a realised building.

In 1975, in a departure from its programme of twentieth-century modernism, the Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition of drawings from the École des Beaux-Arts. The MoMA show sanctioned at once a return to historical sources and at the same time placed elaborate drawings of unrealised projects in a privileged position as artefacts in the museum; among the many consequences of the postmodern turn in architecture was a renewed emphasis on drawing.[2] If Archigram, like Superstudio or Archizoom, or later Hadid and Libeskind, turned to drawing as a realm of experimentation unfettered by the commercial or practical necessities of professional practice, the postmodernists insisted on the historical primacy of drawing in the discipline, now seen through the lens of semiotics, meaning and questions of representation.

In other words, through several circumstances, the recession not the least of them, there was, in New York and elsewhere at that time, a vibrant culture around architectural drawing—drawings were seen as an end in themselves, as works of art even, apart from their instrumental value in practice. The distinction between the discipline and the profession was often evoked, and it was only a few years later Leon Krier would declare that ‘I do not build because I am an architect.’

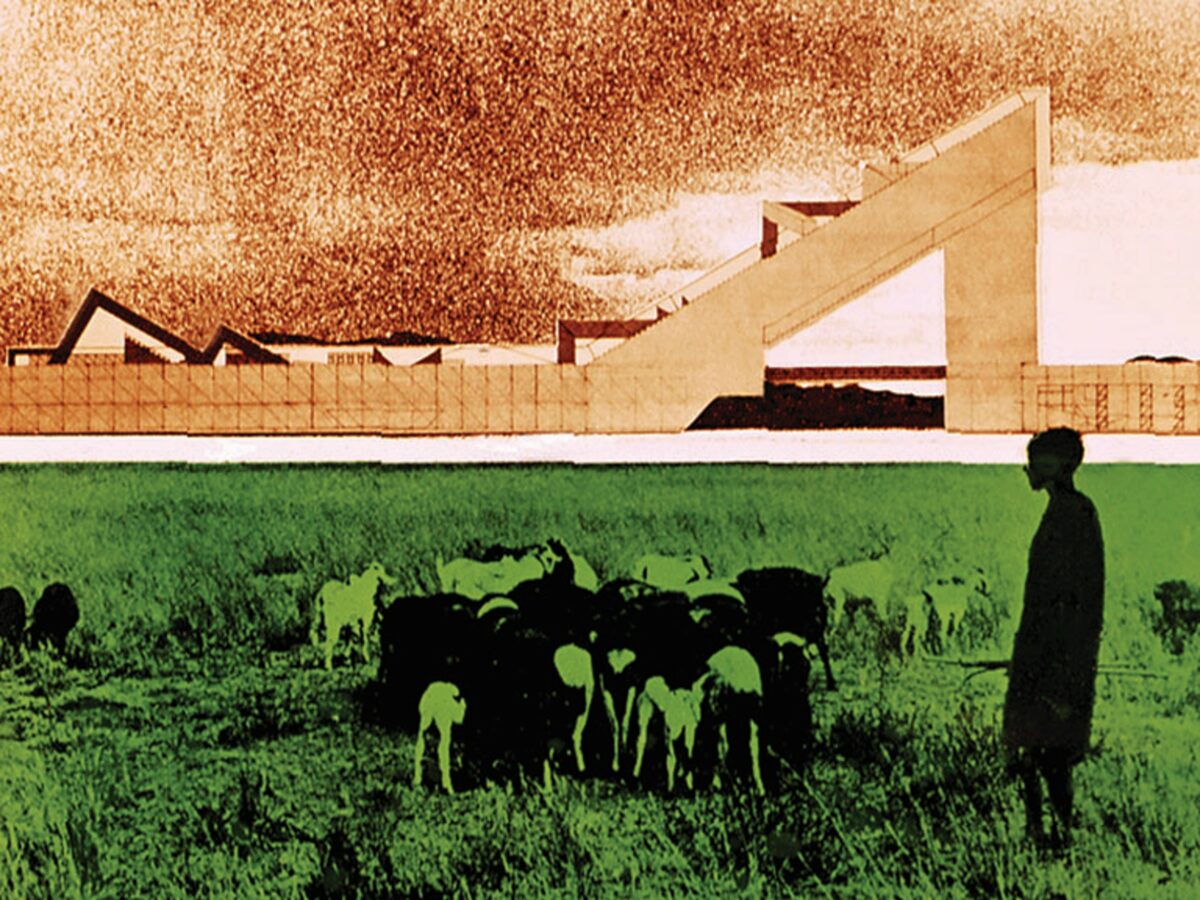

This was the context in which I first encountered the work of Giuliano Fiorenzoli—most likely at the 1978 exhibition, ‘The Image of the Home’ at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. Fiorenzoli had arrived in New York (via MIT) from Florence, one of several young architects and students from that city, taught by Leonardo Ricci, Leonardo Savioli, and Umberto Eco. Collectively organised around ideas of ‘counter-design’ and ‘radical architecture’, they participated in the occupation of the School of Architecture in 1968 and produced drawings and photomontages of visionary projects for large-scale interventions in the city and the territory. Working alongside Superstudio and Archizoom, as well as Gruppo 9999 and UFO, Fiorenzoli founded the Zziggurat collective with Alberto Breschi and Roberto Pecchioli before gaining a scholarship to study at MIT.[3]

In New York, he found another group of like-minded young architects: Steven Holl, Lebbeus Woods, Mike Webb, and Raimund Abraham, with whom he collaborated on the competition design and later the construction of the Rainbow Center Plaza in Niagara Falls (1976). This is the fertile period of work presented in an exhibition at T-Space, the non-profit gallery operated by the Steven Myron Holl Foundation in Rhinebeck, NY. The exhibition includes models as well as drawings, all executed by hand, dating from 1972 to 2016.

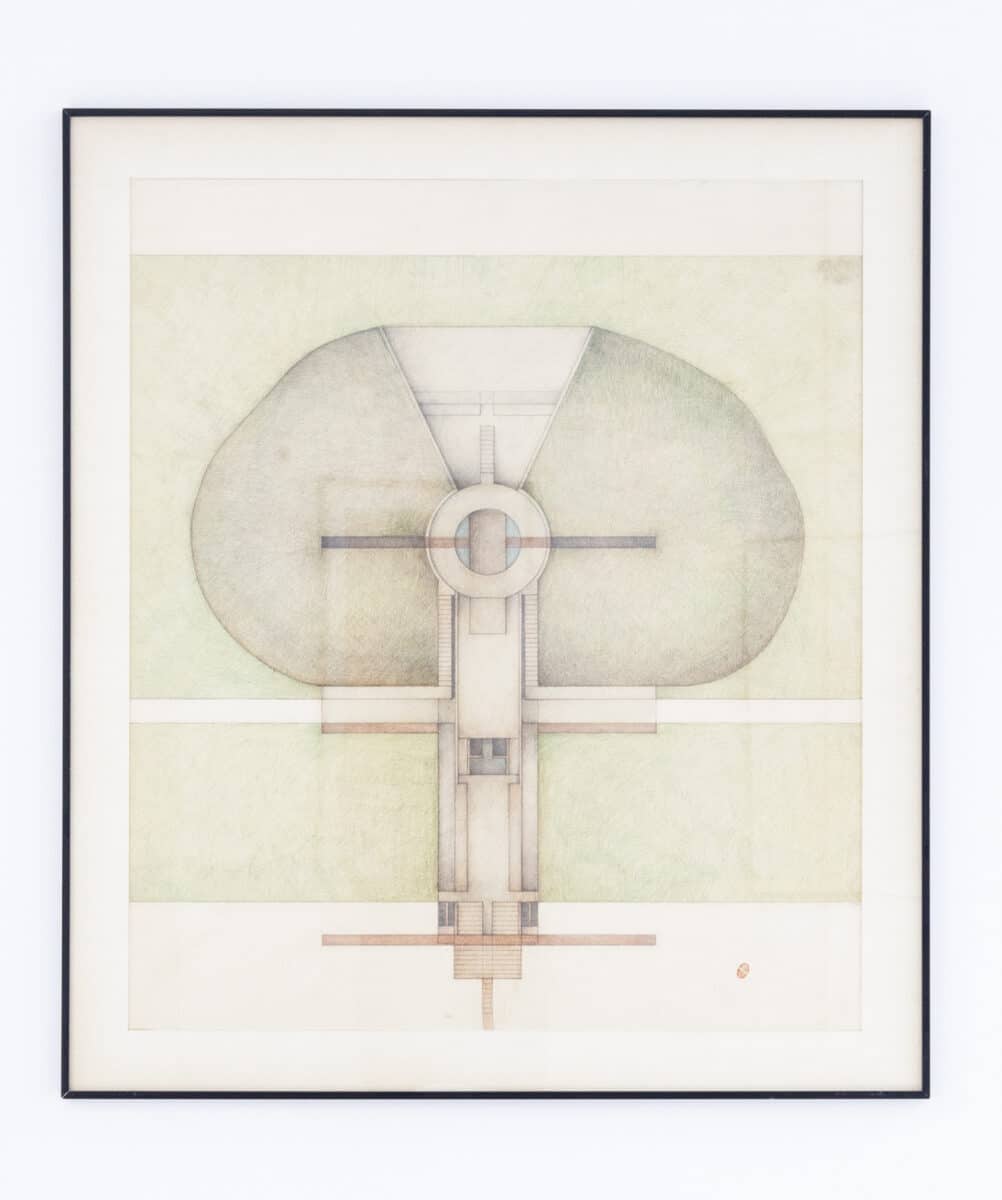

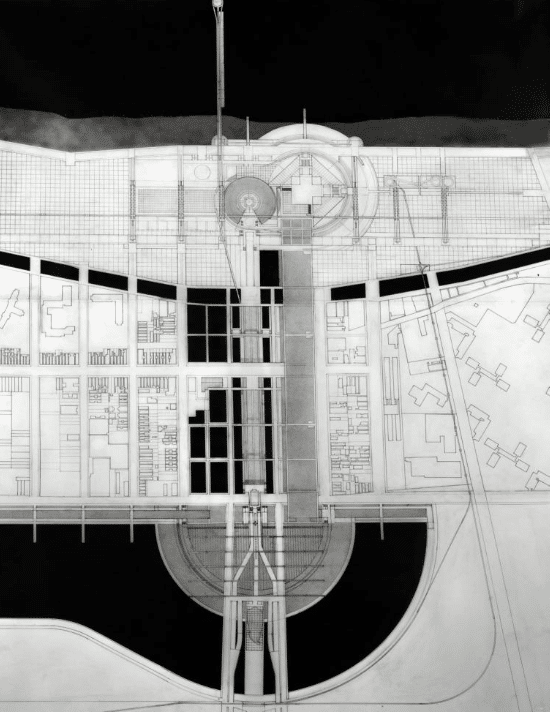

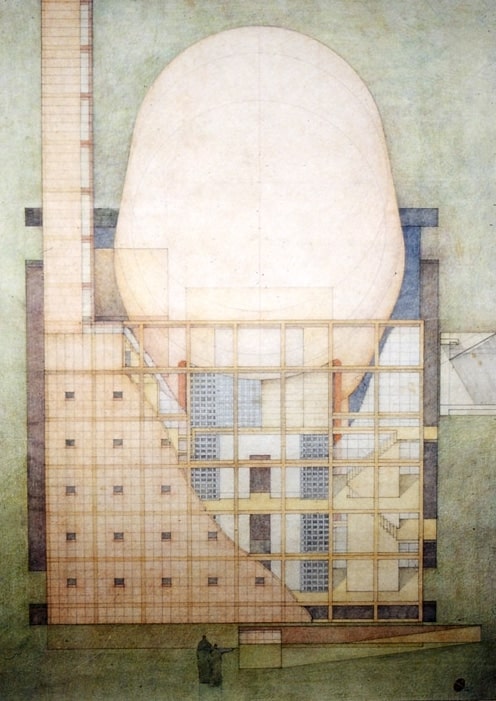

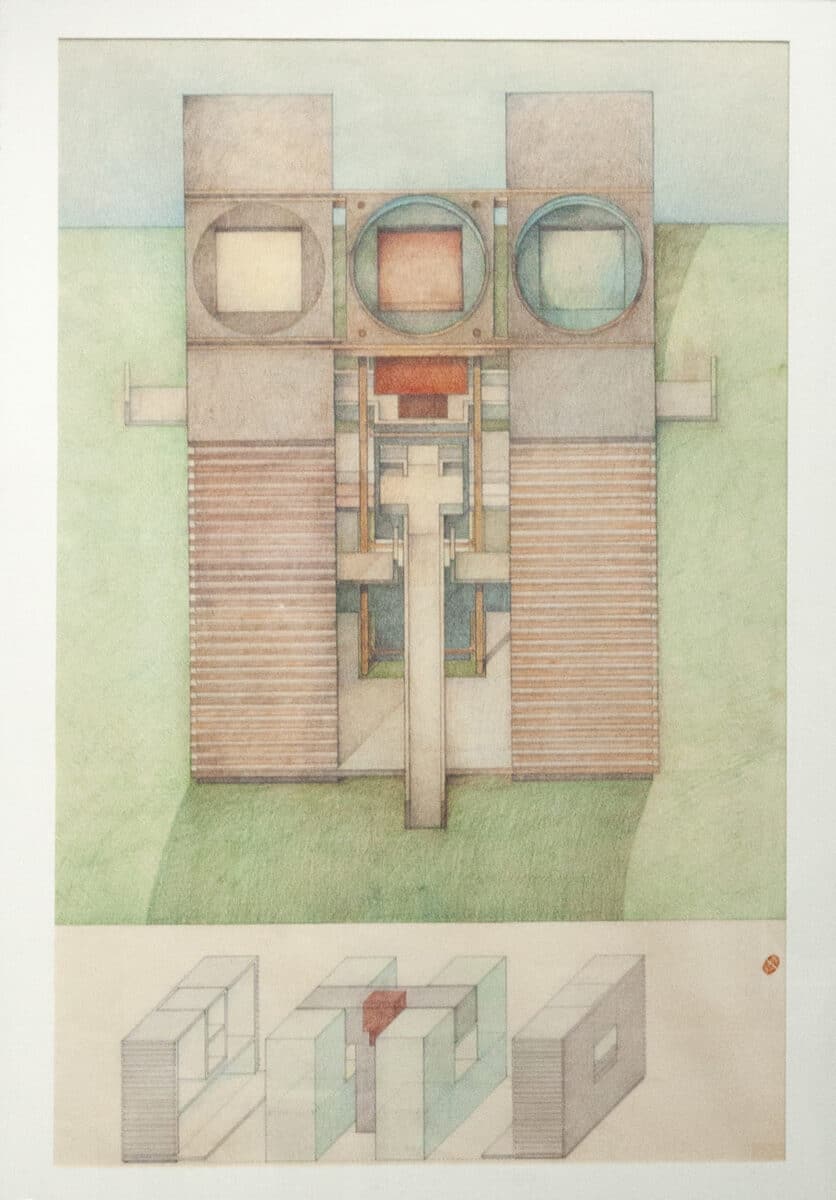

Fiorenzoli has spoken of the importance of the craft of drawing, and each of these drawings is a beautiful object; they reward close scrutiny. They offer the patient viewer a shared experience: the study of a carefully made artefact, the observer participating in the slow and precise work of constructing a drawing by hand. Fiorenzoli lays down a delicate scaffold of pencil lines, mostly on opaque paper with a subtle tooth, sometimes in colour, then gives the structure depth and casts it into relief by casting shadows. He suggests materiality and defines the ground that the structure occupies, all with painstakingly applied layers of coloured pencil, each stroke visible but dissolving into a vibrating field. Fiorenzoli is particularly attentive to the space of the page—the delineated object always has a considered relationship to the ground, the two often merging into one another and filling the space as a unified image. The one departure from the use of coloured pencils is a series of drawings from 1991, much looser and more painterly, with freehand ink lines and tempura.

There are two consistent themes in the drawings presented. The first is the interplay between architecture and landscape. The earliest drawing in the exhibition is the plan of a garden, where Fiorenzoli moves seamlessly from the constructed landscape of the garden (as in the axonometric for the E. Dent Lackey Plaza in Niagara Falls) to the building as a kind of landform—the ‘Hill Top Country House’ in Tuscany, for example, to buildings that partake of the logic and materiality of the landscape, embedded in the earth, or emerging from the ground, as in the 1991 drawings for an ‘Art Museum.’ Drawing titles underscore this shift from object to ground: ‘The Architecture of the Void’ and‘The Absence of Architecture.’

But this is not simply a linear progression; the most recent drawings in the exhibition, from 2016, are for an ‘Endangered Animal Oasis.’ They depict an intricate, concentric waterfront construction, a porous garden-like structure organised around a circular pool.

The second and complementary theme, is a totemic quality to the architecture presented, both in plan and elevation. It is most evident in the masterplan for the ‘Coney Island Waterfront’ (1983), presented in a large-scale plan organised around a central axis that links an inland basin with waterfront structures, which include an iconic ‘white-elephant building sculpture.’ This sense of the totemic character of the object, an iconic form against the horizon, is reiterated in coloured elevations and the use of a 90-degree frontal axonometric, as in the 1978 series ‘Image of the Home.’

Revisiting this work—from that innocent moment before the digital fall—is not without an element of nostalgia. Fiorenzoli is clear on what is at stake for him: ‘This process of digital visualisation of space inevitably overruns the interiority which hand conceived drawings can provide.’ Architecture, he states, is ‘first a discipline, then production’.[4]

Fiorenzoli’s drawings, beyond questions of analogue vs. digital media, serve as a means to reflect on the essential characteristics of architectural representation. These drawings are at once self-sufficient as works of art, autonomous and complete, and at the same time, projections of an imagined reality: scripts or scores for an alternative future. The best architectural drawings always operate simultaneously in both registers, some favouring autonomy, some tending toward instrumentality and translation. Fiorenzoli’s drawings lean towards autonomy; they are fully realised aesthetic objects but they never lose sight of architecture’s projective capacity. It is evident in the tectonic clarity of Fiorenzoli’s structures, both the insistent presence of the trabeated frame and the clear grounding in the earth, as well as in the precision of the geometric scaffolding that underlies the sensual surface of these drawings. Familiar architectural elements, even scale figures, anchor these dream-like landscapes in an intelligible, if somewhat idealised reality. It is easy to imagine these structures built, and Fiorenzoli has maintained a modest professional practice for many years, realising houses in Italy and the US as well as carefully detailed interiors in New York City.

A friend once remarked that treating an architectural drawing as an aesthetic artefact is like admiring the handwriting on a Mozart score. It’s hard not to argue that the true artistry lies in the experience—dense, complex, and irreducible—of the music performed or the building as realised. But I don’t think this is an either/or question. Architecture works through ideas and images as well as buildings, and the paradoxical double life of the architectural drawing—as a self-sufficient work, complete in and of itself, and simultaneously as a projection of an imagined future reality, is something to be embraced, not rejected.

Giuliano Fiorenzoli, ‘Because of Seeing Architecture’ was on show at T-Space, Rhinebeck New York, from October 15 to November 19, 2023; planned to be installed at the Pratt Institute in 2024.

Stan Allen is the principal of SAA/Stan Allen Architect and former Dean of Princeton University School of Architecture.

Notes

- Protetch’s gallery opened in 1978. It was the first commercial gallery to prominently feature architectural drawings, and to represent architects. Protech intentionally blurred the boundaries between architecture and art; drawings and models by architects were exhibited alongside works by artists such Siah Armajani, Alice Aycock, Scott Burton, and Will Insley. The first exhibition of drawings by Michael Graves in 1979 sold out and helped to promote the idea of a viable commercial art market for architectural drawings. He would often partner with the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, which held parallel exhibitions and published catalogues, as was the case with Rossi, Hejduk, and Scolari.

- ‘The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts’, Arthur Drexler, in collaboration with David Van Zanten, Neil Levine, and Richard Chafee, Oct 29, 1975–Jan 4, 1976. See also, America Now: Drawing Towards a more Modern Architecture / AD Profile 6, 1977, edited by Robert A. M. Stern.

- ‘The name Zziggurat refers to one of the icons and graphics from the Pop Art production of the time. It is a bit of a cartoonish and playful image affecting design in search of a new beginning.’ Giuliano Fiorenzoli, email to the author, 06/12/23.

- Giuliano Fiorenzoli, ‘A Point of View’, pamphlet produced by T-Space to accompany the exhibition, 2023.