Portals: The Visionary Architecture of Paul Goesch (2023) – Review

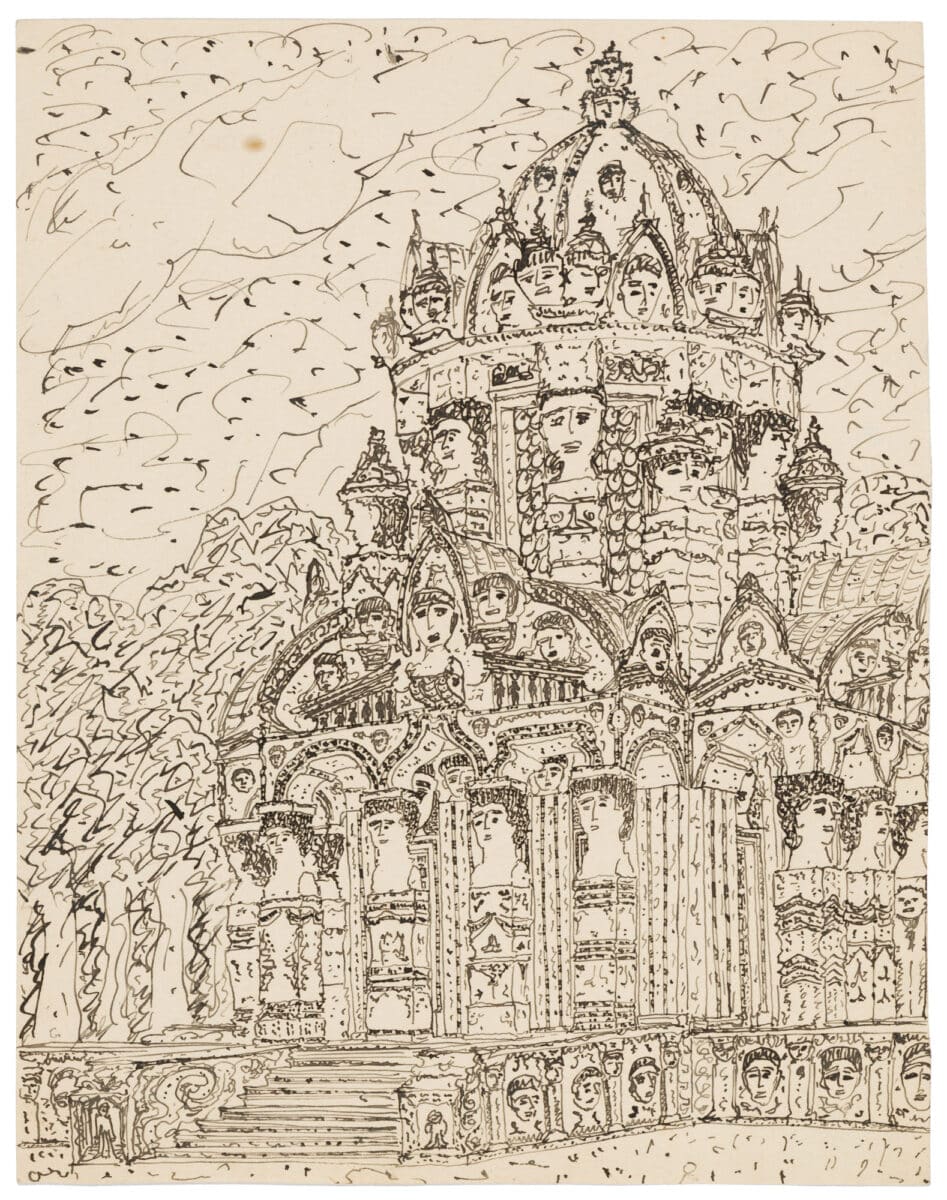

Paul Goesch was forcibly detained in a psychiatric hospital and, in 1940, murdered by the Nazis. Looking at these intense, yet often playful and exuberant drawings, it is impossible to forget the stark facts of his life. Which is unfortunate, because an exclusive attention to his personal history imposes a tendency to see this work through the lens of victimhood, or to relegate Goesch to outsider status. His work was reproduced and discussed in psychiatric journals at the time, and, it is not unusual (at least online) to see him classified as an ‘outsider’ artist. And, along with other avant-garde and expressionist artists, he was included in the 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition.

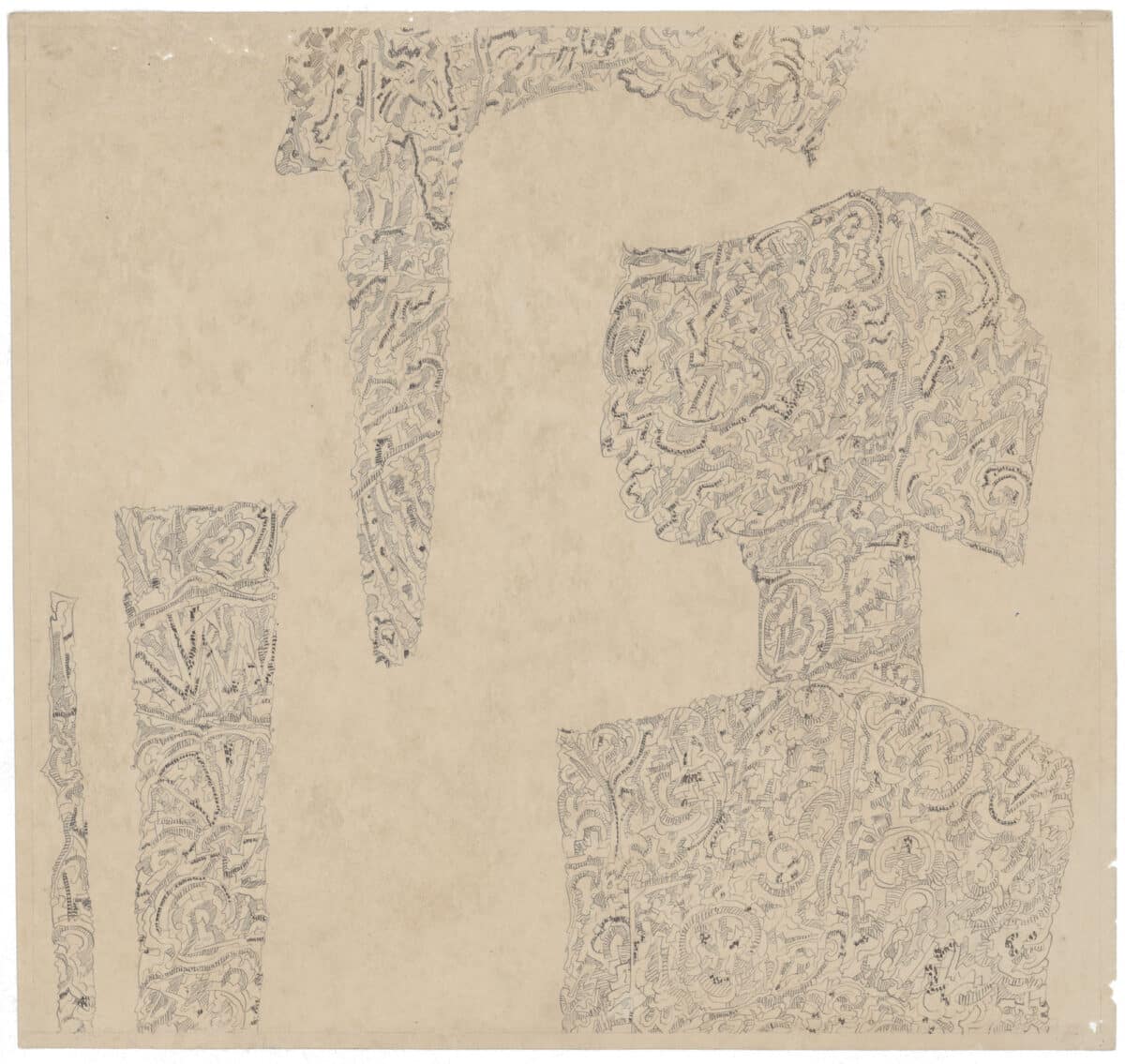

Goesch’s mental illness was real (although likely treatable) and while some of his line drawings bear an uncanny resemblance to those of Martin Ramírez (a self-taught artist whose intricately patterned drawings were made while he was a patient at DeWitt State Hospital in northern California), Goesch’s drawings also recall Paul Klee in their delicacy, the play between figuration and abstraction, and their sensitivity to surface, colour, and space. Portals: The Visionary Architecture of Paul Goesch, a recent exhibition organised in cooperation with the CCA and shown at The Clark Institute (18 March – 11 June, 2023), offered an wider perspective on Goesch’s work and life, and a rare opportunity to see these extraordinary drawings in person.

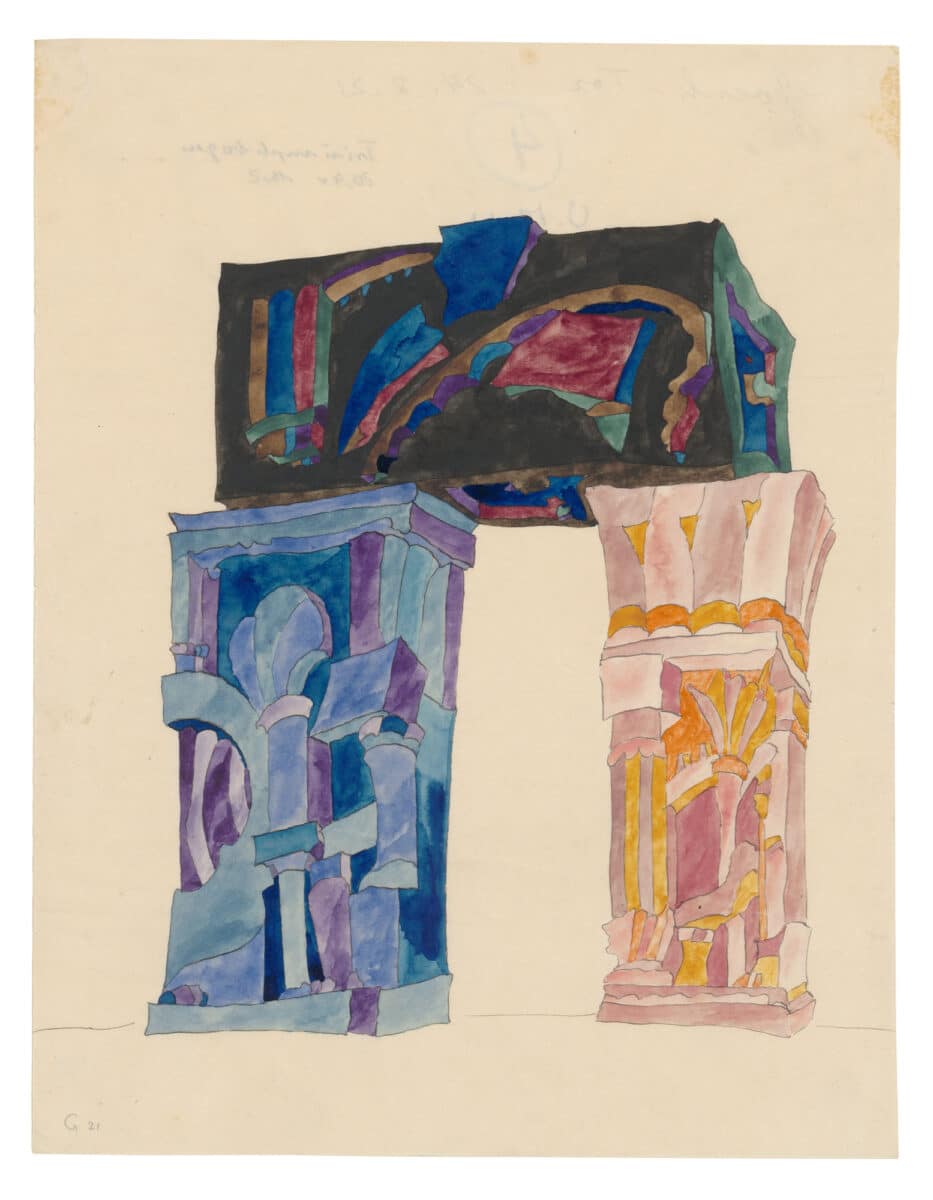

Goesch was not an outsider. His family was well-off, and he studied architecture in Munich, Karlsruhe, Dresden and Berlin (although the frequent moves might already suggest a certain restlessness). His work was exhibited in his lifetime, and he was an early member of the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, the art-workers cooperative that included Lyonel Feininger, George Kolbe, Walter Gropius, and Erich Mendelsohn. Goesch was part of the circle around Bruno Taut and contributed to the Chrystal Chain letters. At The Clark, his drawings were contextualised with work by Taut, Hermann Finsterlin, Käthe Kollwitz, Wassily Kandinsky, and Max Beckman, among others. A student of theosophy, he joined Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society in 1913, and took part in the construction of the first Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland. A self-portrait from 1920 is titled, perhaps in irony, ‘I Will be Famous.’

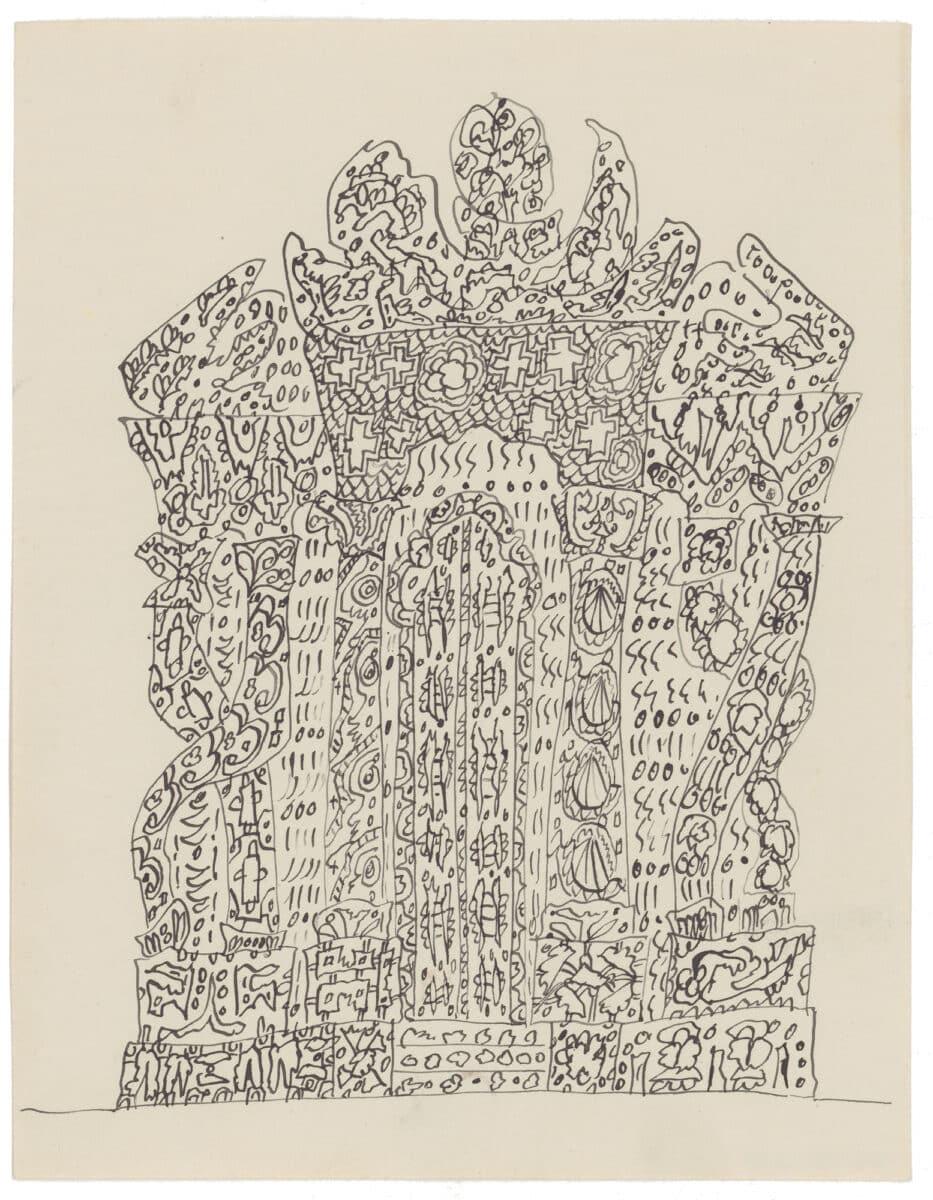

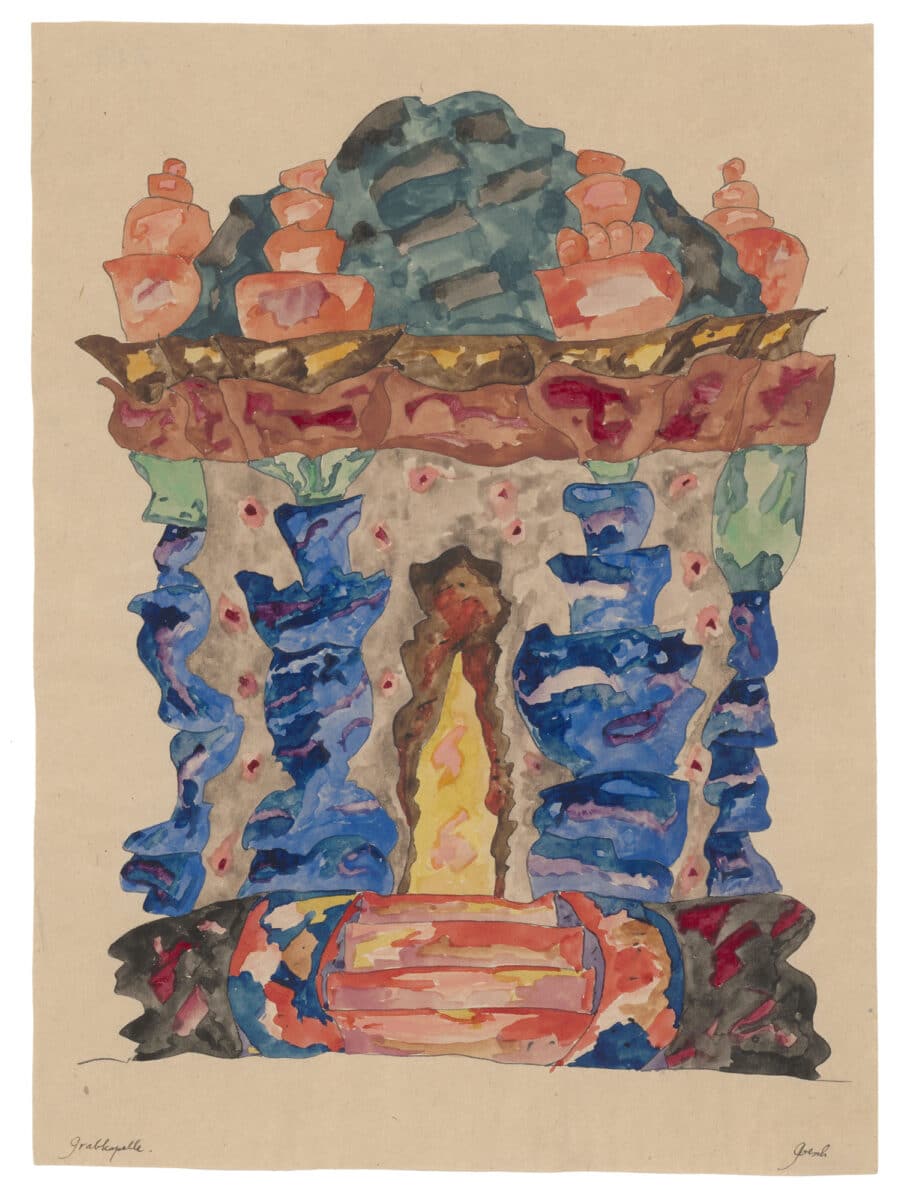

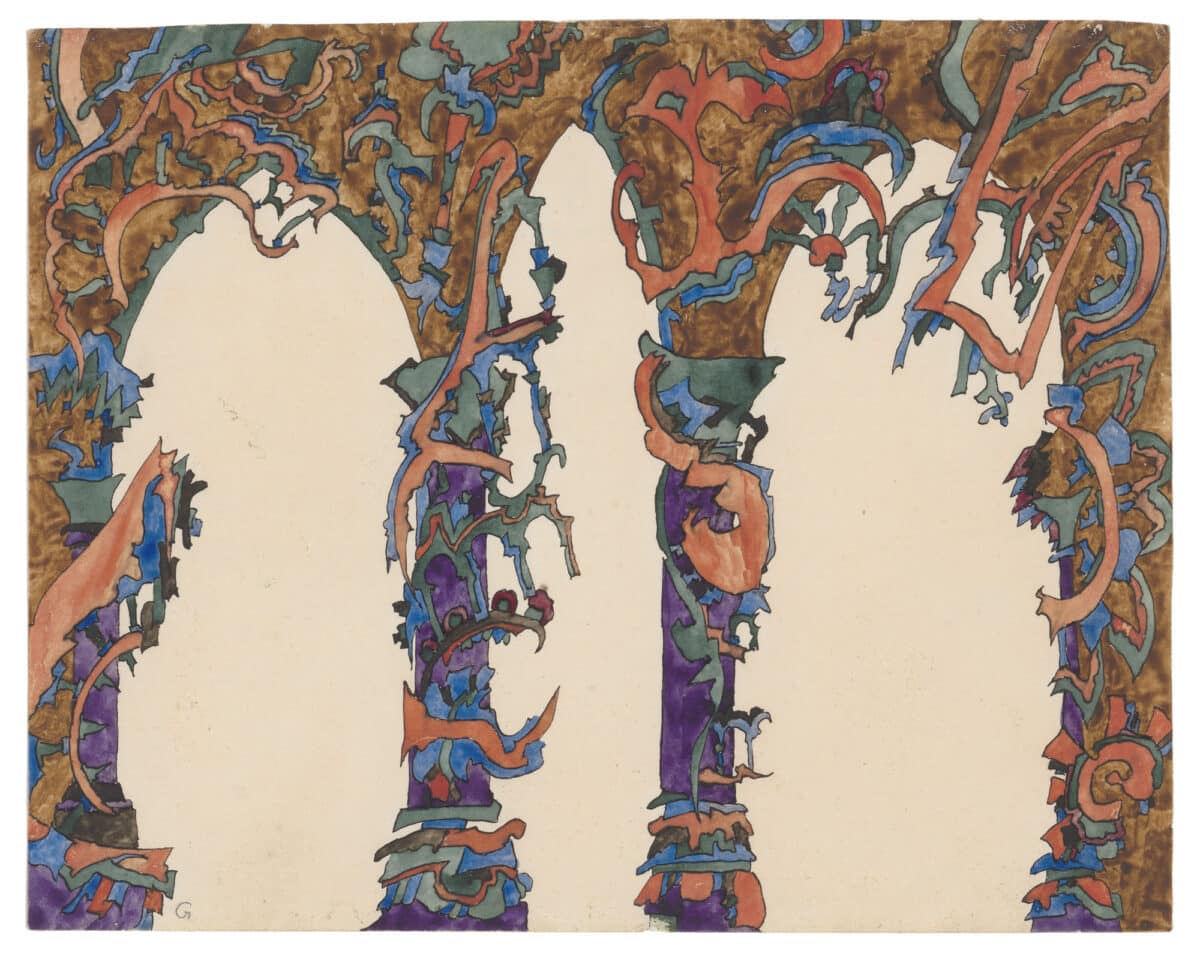

‘Portals’ is an apt title. There are literal arches and gateways, but the allusion is to drawing as a passage from profane to sacred: a doorway to a transcendent state of being, both spiritual and utopian. Insistently frontal, recalling architectural elevations, Goesch’s gateways often have an organic and figural quality, an aspect of his work that speaks to the many depictions of the human face among his surviving drawings; human faces and architectural facades are made equally expressive. These suggestive fragments are often shown on a lightly drawn ground-line, gently curved to suggest that the structure occupies the crest of a low hill, a site of worship or the goal of a pilgrimage. But often as not, there is no ground-line at all, and the space implied is more expansive, and abstract.

Goesch’s colours are vibrant and rich, and these drawings speak to a sensitivity to the space of the page as much as to the space of description. Goesch had a sophisticated awareness of the blank space of the paper and the placement of image in the field of the drawing. The drawings are small, and the viewer, whether of the exhibition or the book, has an intimate sense of the movement of the hand over the paper.

Many, if not most, of the drawings are painterly, describing form and space with blocks of colour, or suggesting the play of light on intricately faceted shapes; others (for me some of his most compelling), work with line, sometimes coloured lines, suggesting a dense weave of surface. The lines crawl over and off the edge of the page, intertwining in textile patterns informed by organic growth.

The catalogue includes texts that give a full background and context for Goesch’s work and offer new interpretive frameworks. The drawings are reproduced at close to full scale, respecting their character as objects. The Clark presentation emphasised Goesch’s architectural training and the ‘visionary’ architectural character of his drawings. Working from the CCA’s holding, this is understandable, but it is not the full story of Goesch’s body of work. A viewer seeing only this exhibition might not be aware that it represents only one facet of a wider, and more varied painterly and graphic production. Architectural drawings are always at once self-sufficient works, and at the same time notations for imagined buildings and spaces. While this is certainly true of Goesch’s drawings, I believe that Goesch is better understood not as a failed, or frustrated architect, but as an artist with a deep spiritual yearning who took architecture as one among his many subjects.

Robert Wiesenberger and Raphael Koenig, Portals: The Visionary Architecture of Paul Goesch (2023) is published by Yale University Press. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Stan Allen is principal of SAA/Stan Allen Architect and former Dean of Princeton University School of Architecture.