Leto Litho Leningrad

Joseph Brodsky, in his short essay ‘A Guide to a Renamed City’ (1979), wrote:

The characteristic features of Leningraders are: bad teeth (because of lack of vitamins during the siege), clarity in pronunciation of sibilants, self-mockery, and a degree of haughtiness towards the rest of the country. Mentally this city is still the capital and it is in the same relation to Moscow as Florence is to Rome or Boston is to Washington…Leningrad derives pride and almost a sensual pleasure from being unrecognised, rejected, and yet it is perfectly aware that, for everyone whose mother tongue is Russian, the city is more real than anywhere else in the world where this language is heard.

Brodsky was born and spent much of his life in Leningrad but was exiled by the Soviet authorities in 1972, never to return. Leningrad was for him a distant memory, an emotional location both lost and longed for.

Лето – leto – pronounced lieta – Russian for summer.

In 2017 there was a small exhibition of Leningrad lithographs in the former flat of the poet Anna Akhmatova, in a block just behind the Fontanka canal. Akhmatova’s life stretched back to the tsarist period. She had died in 1966, surviving any amount of periods of political change, and living into the period of these lithographs. A selection from this first show was recently shown at the Estorick gallery in Islington. The art collector and dealer Eric Estorick had originally collected these lithographs in the 1960s and 70s during the presidency of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, following the comparative freeze of the years of Nikita Khruschev. They suggest various reflections on the unusual nature of both the city and its images.

Leningrad, founded by Peter the Great (who referred to the city as paradise), realised the tsar’s great venture to build a European city on the banks of the Neva. It was a mix of Paris, Venice, Amsterdam, London and others, but with its own identity. The city had endured the terrible siege in the Second World War, when one million people died from starvation and shelling. The inner city was reconstructed, rebuilding what had existed rather than creating anything new. A version of its former self – as much from lack of economic means as from any particular purpose – in the postwar years, Leningrad retained its reputation for gloom and cold, and its time appeared to be over.

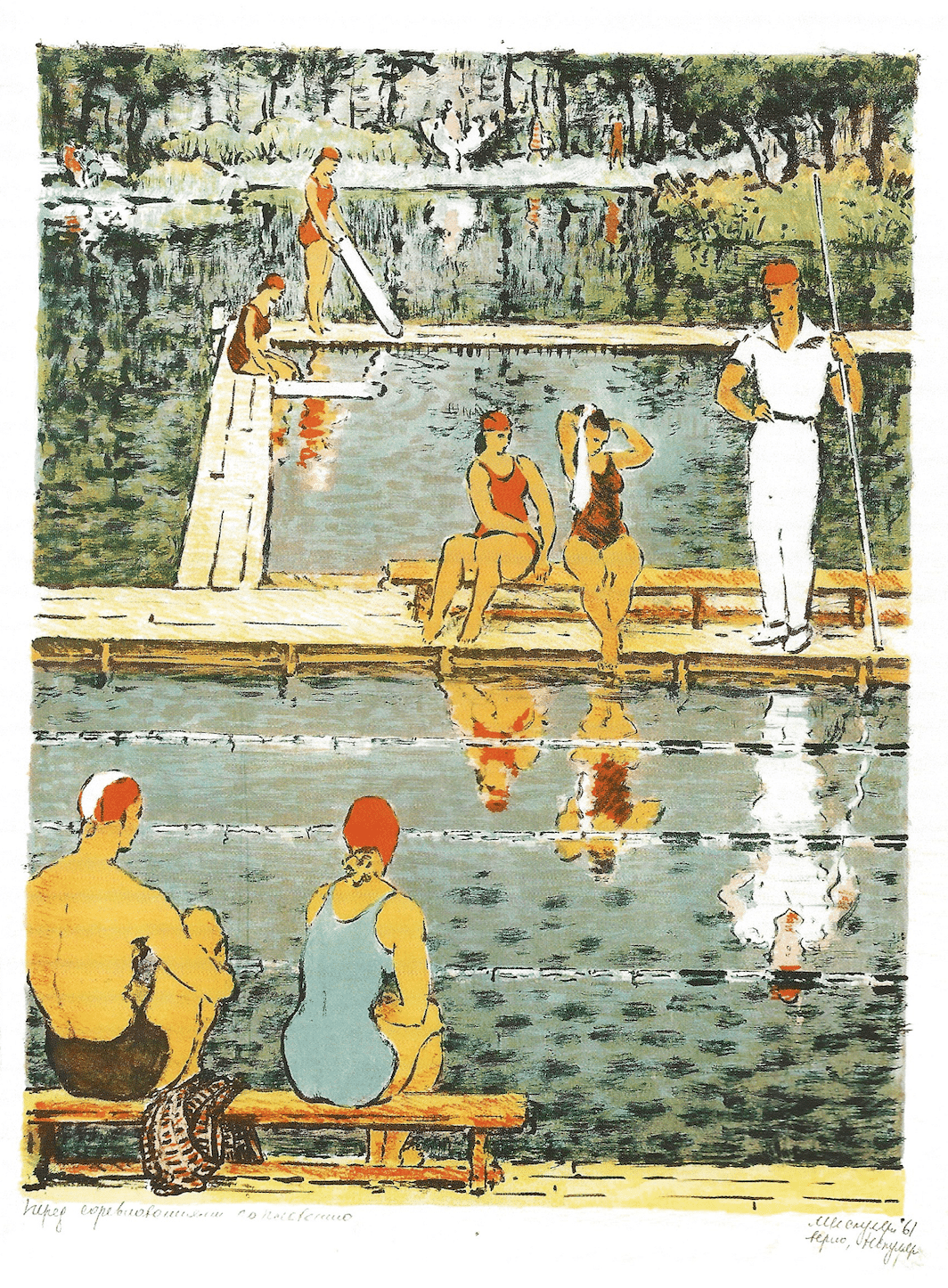

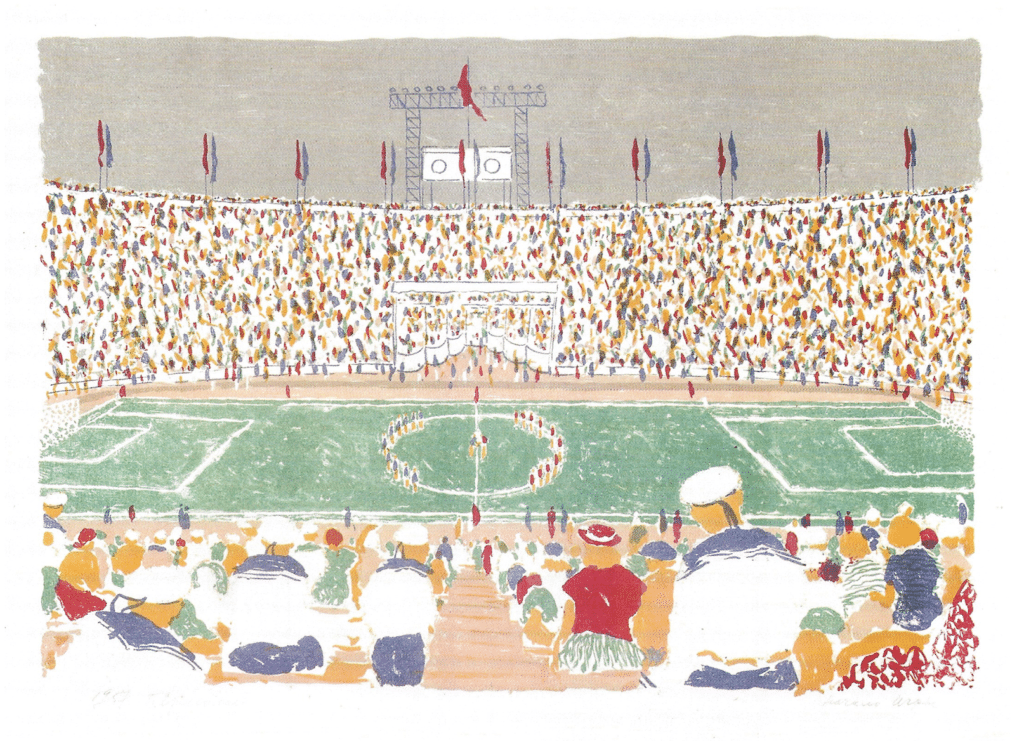

However these lithographs, and others made at the same time in the Leningrad Experimental Graphic Laboratory, reveal another side to the city, where it is sunny, grand, optimistic, more Mediterranean than Baltic. One of the earliest is Anatoli Lvovich Kaplan’s Summer Garden, a moody scene of a bridge and a giant urn dwarfing two children on a sledge, a wonderfully delicate composition which appears to flicker out of pre-revolutionary Petersburg. Irina Nikolaevna Maslennikova’s Station Lights, from 1959, with rail tracks and a rather shaky looking bridge filled with people carrying umbrellas has the feel of a Japanese woodcut. Then there is the funky, Matisse-inspired Leningrad, full of colour and light. Aleksandr Semenovich Vedernikov’s (ah, what wonderful names, together amounting to the nomenclature in some nineteenth-century Russian novel…) Marakov Embankment, 1960, has a purple Neva and a cheerful green boat. His Circus Artists on the Highwire is a dramatic mix of yellow foreground, purple background and bright red for the trapeze artists. Aleksandra Natanovna Latash’s At the Beach has striped umbrellas and mats, and could well be on the Venice (California) seaside rather than on the banks of the Neva. Boris Nikolaevich Ermolaev’s The Start of the Game shows the Leningrad football stadium, home of the legendary FC Zenit, with the green of the pitch set of against blue and white naval uniforms.

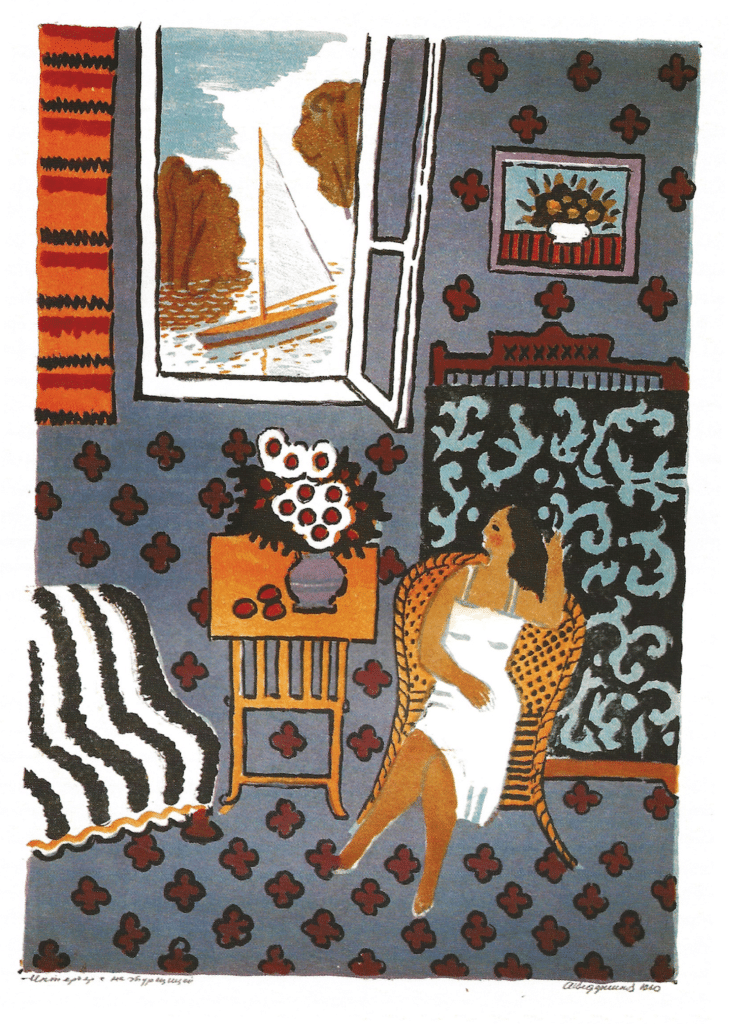

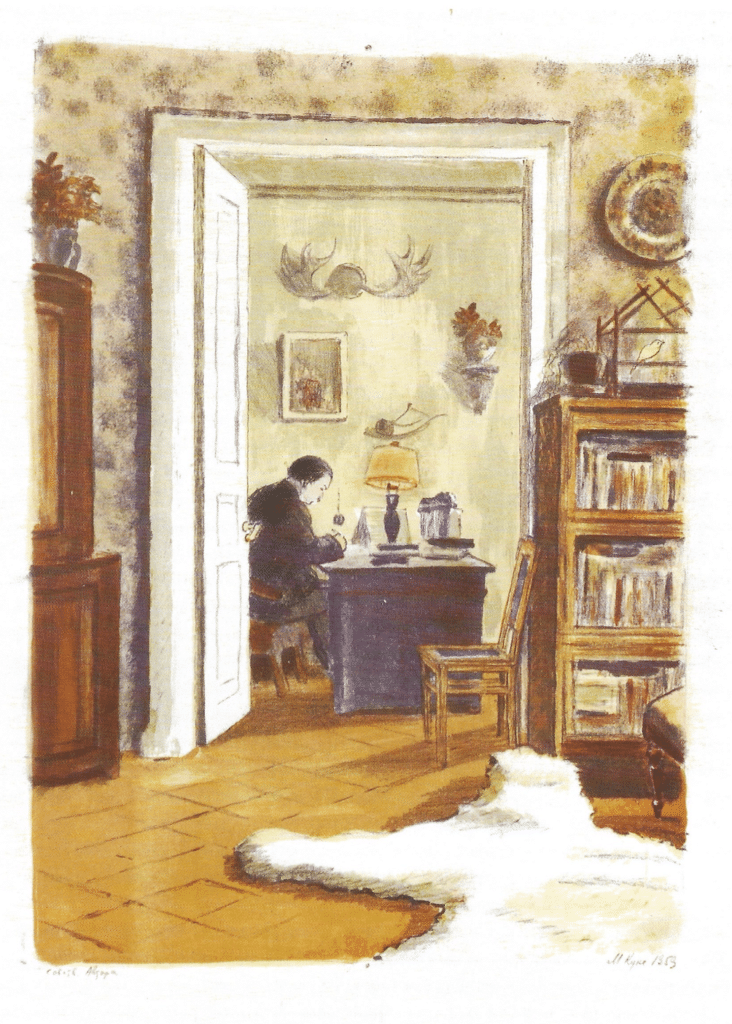

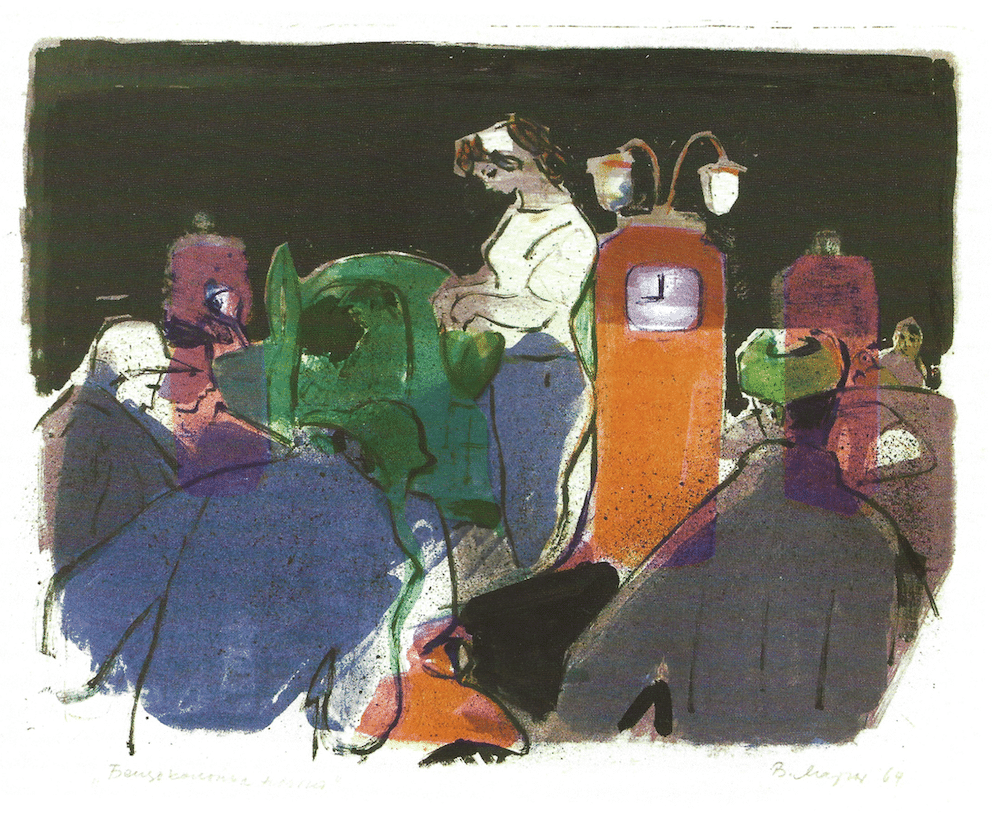

The people these lithographs portray are hardly the usual glum soviet types (that we know from stereotypes in the western press). Boris Nikolaevich Ermolaev’s Girlfriends, 1962, has two – or maybe four – women, with slightly Italianate faces, wearing colourful scarves. Vera Fedorovna Matyukh’s Petrol Station Queen is a wild display of reds and yellows, and here tanking in Leningrad is revealed almost as musical performance. Minei Iliich Kuks’ In the Study has all the right accoutrements every decent Soviet writer might need, including a polar bear rug on the floor. In Aleksandra Semovich Valernikov’s Interior with Woman, a woman in white lounges in a wicker chair in a room inspired by Matisse, a window gives a view of a passing sailboat.

This dreamlike state flickers through all the lithographs. From just what background do they emerge? Are they intended to be realistic – in a state proud of its social realism? Or do they project an imaginary Soviet Union? It is often assumed that the art of the Soviet Union was cut off from the west, and also that following on from social realism it had little original material to offer. But both of these assumptions are untrue. Leningrad was a great Baltic port, and because ports can never be completely controlled, they always have links to the exterior. In the endless galleries of the Hermitage, the former palace of the tsars, which is more like a city than an art gallery, amongst many other works is a fantastic collection of artworks made prior to the First World War by Matisse, Cezanne, and Raoul Dufy, which clearly inform the style and colouring of the lithographs. The Leningrad lithographers were in part recreating the innocence and freshness of the French modernism of half a century before, albeit in a very different society. Soviet artists did travel abroad – for instance Aleksandra Yakobson, who came originally from the Siberian city of Irkutsk, made journeys to Sweden and England, producing ironic portraits of the sexually liberated Swedes and a series of sketches of England, reimagined as sort of Russian colony with colourful houses and men on red scooters.

This diverse group of artists had little interest in the avant-garde art experiments of abstract art going on at the time in the US and Europe – perhaps because such work was banned pretty much until the end of the USSR, and perhaps also because it didn’t particularly interest them. It was not part of their world. They were concerned with developing a technical skill, for lithographs are complex to create, requiring extensive training and then careful work preparing the stone, laying out areas which are either greased or wet depending on how they take the colour, and printing with calculated pressure onto particular types of paper. The Leningrad Experimental Graphic Workshop was an unusual institution: state-sponsored but allowing each artist to follow their own path. Although entirely non-political, the LEGW often ran into difficulties with authorities because of suspected contacts abroad. Yakobson wrote in 1963: ‘It is considered to be the main hotbed of dissent. For three days the people from the central committee were checking all the folders of lithograph prints and, most of all, the guest book.’

The artists in the workshop cared in particular about the effects only lithography could create, such as the delicate floating sky over that railway bridge and the splashy colours of the petrol queen. They loved to create contrasting blocks of colour, pinks, violets, yellows, as in Japanese prints. These lithographs were created as multiples, to be shown not in galleries but (because the workshop was state-funded) in schools, hospitals and other institutions.

Many of the images have a narrative quality. These works relate back to the Russian tradition of illustrated books – many of the artists involved with the LEGW worked on children’s books both for professional reasons and because such projects were not subject to political requirements. Yuri Alekseevich Vasnetsov created wonderful images of animal fables: a cat marrying an unwilling foxy lady, another cat at table contentedly devouring kasha porridge, prancing horses with orange manes. Yakobson also illustrated many books, showing women both as traditional Russian figures, part of the family, but also as fleshy, erotic, and more compelling than the men around them. Folk art glorifying peasant life was a standard trope of the USSR, in spite of the glorification of industrialisation, but there is something more going on here, a touch of pop.

Leningrad was always both magnificent and seedy – that is its charm, which emerges in its literature, from Gogol’s dubious figures with their wandering noses and overcoats, through Akhmatova and the golden period to writers of the 80s and the post-Soviet period like Elena Andreyevna Shvarts, where the city in its scuzzy state is still a personal ideal:

What is the whole town is called – you find out from a passer-by

For me it’s called – my paradise, my lost paradise

And because it’s lost – its parks still blossom…

There black rats scurried in the shrubs beside the shining river

Admitted, allowed, nothing spoils this paradise on earth

This version of Leningrad reappears in Kirill Semyonovich Serebrennikov’s film Leto, released in 2018 but set in the early 1980s. An early scene and also the final image are set on a Baltic beach similar to that of Latash’s sunny 1960s scene. The story is of two rock bands fuelled up on David Bowie, Iggy Pop and Talking Heads, fascinated by the culture of the west, borrowing and imitating but creating a culture of their own – as Leningrad/Petersburg has always done. This music creates again that state of dreaminess, of being both in everyday Soviet reality and also somewhere else. In some scenes, the film resembles a version of an American musical, with chunky Leningrad citizens in ancient trams belting out the sardonic music of the capitalist enemy. The film is shot mostly in black and white, with flashes of colour, as though the Soviet city is illuminated by an unexpected sunshine from elsewhere. Leningrad has always declined to fit any idea of what either a Russian or a European city should be.

Лето!

Я изжарен, как котлета.

Время есть, а денег нету,

Но мне на это наплевать.

а-а-аaa

Summer!

I am frying like a meatball.

There is time, but no money,

But I don’t give damn.

ah-ah-ahhh