Lisson 1 + 2

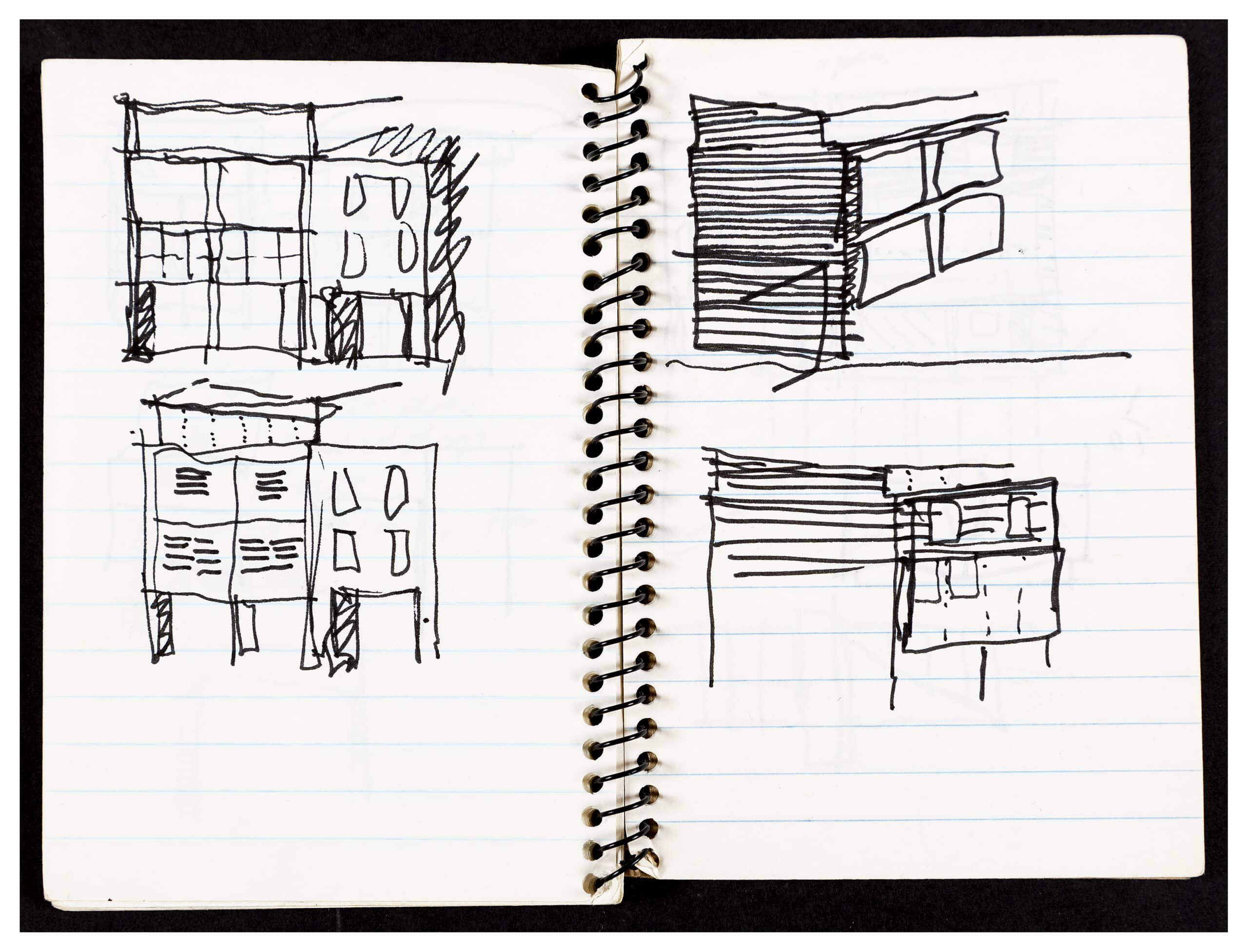

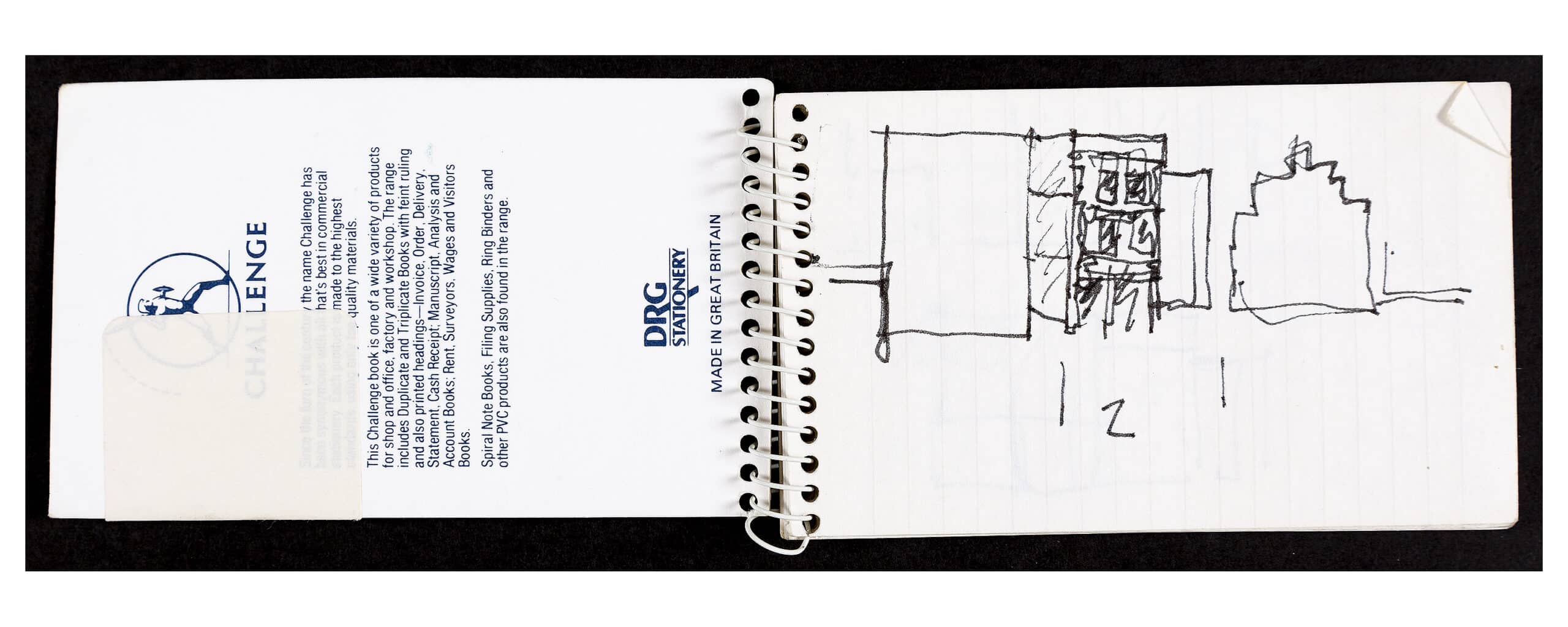

LISSON GALLERY 1, 1986.

Bell Street, London NW1

Tony Fretton, Michael Fieldman, Ruth Aureole Stuart.

We were invited to discuss a new building for the Lisson Gallery. Meetings took place in the office of their existing premises, that the Director and his colleagues shared. To reach it you walked in from the street through unguarded exhibition spaces, down past a storage area and into the basement. Works by artists such as Donald Judd, Sol Lewitt, Tony Cragg and Richard Deacon lay awaiting shipping or were informally displayed on the walls of the office. The Gallery felt at ease in its peripheral location, away from the London art quarter, and had acquired a site nearby for the new building in a terrace of partially occupied and wrecked buildings.

Our first schemes were intoxicated by the tactility of the site and the possibility of art being shown in settings made by the quiet action of disorder. But these visions had to be sublimated into the detail-less language of art buildings for the Gallery to establish its international status, and they resurfaced as romantic spaces made from the bare facts of location and use.

The site is narrow at the front, widening at the back into an area that was added after construction started. The extent of the space is not apparent from the entrance and is discovered only by walking into the depth of the building. Its natural shape is strange and sometimes contradicts one’s perspective.

Daylight enters the front gallery through the translucent glass of the entrance screen, and a skylight at the back of the gallery illuminates the floor for sculpture. Electric lighting provides more controlled illumination of the walls that suit paintings. The entrance screen and skylight are visible from most parts of the galleries so that the exhibition spaces seem to be entirely daylit. The front gallery is narrow with a wooden boarded floor, and steps down to the back gallery where the acoustic is made different by the room’s larger size and paved floor. A gallery in the basement has a single view through the door to the back gallery, conveying the presence of daylight at a distance.

The existing facade and entrance screen, and the domestic rooms above the gallery are treated as known types from the language of building, so that as far as possible their formalisms will be distinct from those of the artworks on display. Their resemblance to similar items in other countries is intended to create a sense of placelessness to underline the Gallery’s internationality. The character of the spaces is established in ways that are experienced rather than seen so that the art on display predominates.

To reach the district where the new building is located requires special effort. The forms of the streets through which visitors come continue into the building but become quieter and more reserved. The rooms are still unguarded and the offices difficult to find and in the depth of the space there is nothing between you and the art.

Since completion the building has been altered with care by the Lisson Gallery and by the connection, we made to the new Lisson Gallery 2.

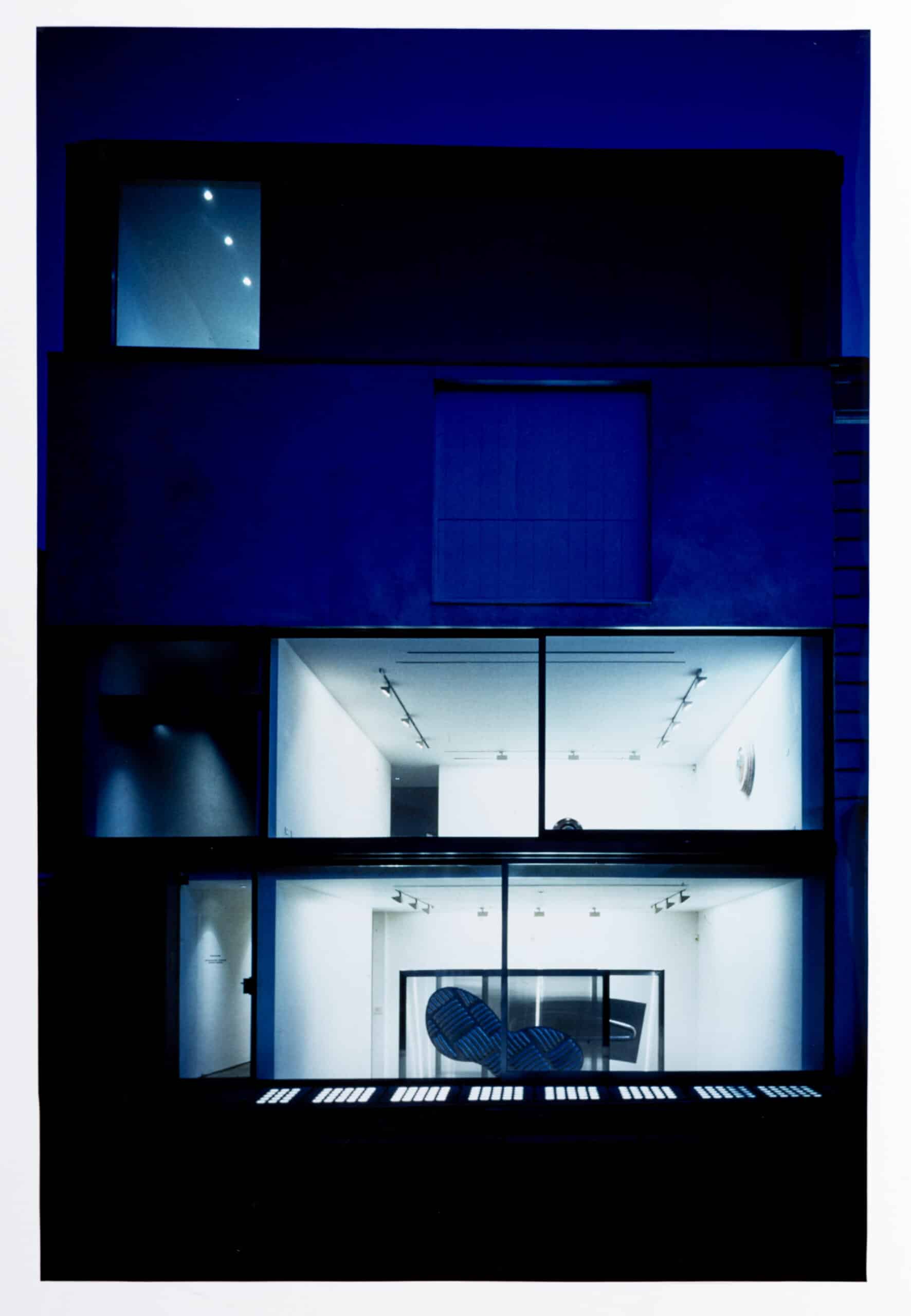

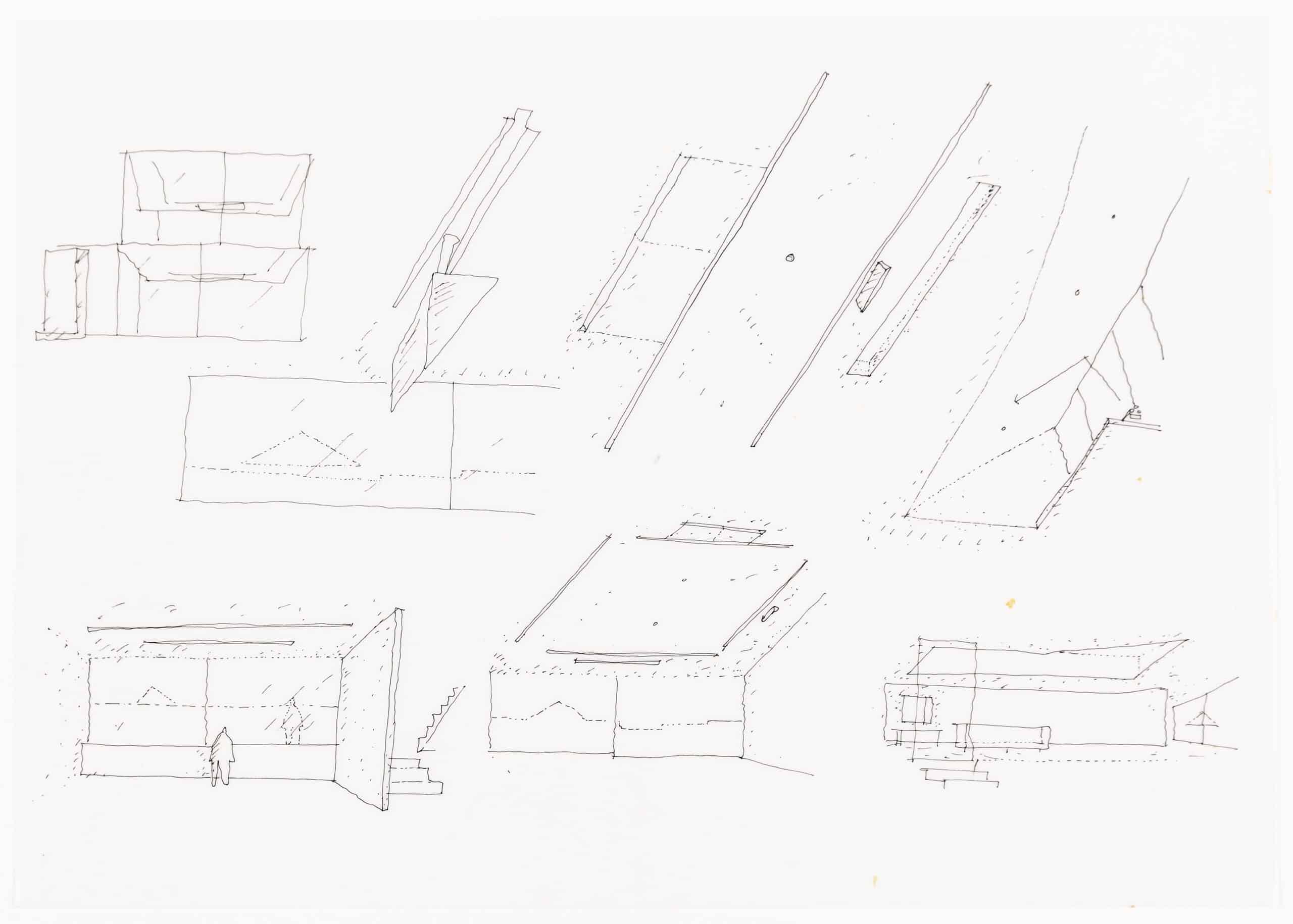

LISSON GALLERY 2, 1992.

Bell Street, London NW1.

Tony Fretton, Michael Casey (Project Architect), Pia Petterson, Karen Tiedeman.

The second Gallery is a short distance from the centre of London in an area that was laid out in the 19th century as houses and shops. Their sites are often distorted by the lines of land ownership or proximity to the junctions of streets, which does not easily allow for the construction of a larger building. The school, the office tower and elevated highway broke the original fabric into fragments and became fragments themselves, surrounded by space where social engagement was more difficult, although a local community continues to exist, and people choose to come and live here.

There is a market in the street outside the Gallery on Saturdays and a school where the playground fills with children at break time, otherwise it is quiet. Almost unobstructed north light comes across the playground into the Gallery windows, giving composure to the exhibition spaces despite them being very exposed to the street. The exhibition spaces are medium sized, around six metres in width and length. They are arranged as single rooms in the basement, ground and first floor and can be understood separately, or as part of an ensemble with the others and the differently scaled and configured rooms of the earlier building we made for the Gallery to which this building is connected. The first floor is 2.7m high and is made for small and medium sized works, although its horizontality can be used dynamically for larger pieces such as Dan Graham maquettes. The daylight on each wall is slightly different due to the varying density of buildings outside. The ground floor is 3.6m high and the light enters steeply and in a great quantity. It has a large presence, and medium to large pieces of work can be displayed well there, especially single works on the wall, or sculptures and installations that nearly fill the room. The basement is longer than the ground floor because it extends forward beneath the street. Daylight entering through lenses in the pavement provides variable illumination on one wall while the other walls are artificially lit.

Dimensions vary on each floor, are unequal in each room, have no proportional relationships and were outcomes either of the site or decisions made by eye. The rooms are intended to have the unforced character of open spaces like the school playground, which have occurred incidentally, and to uncritically frame views of them, the neighbourhood and city. Similarly, the street facade of the second Gallery is made of the interior of the rooms and reflections of surrounding buildings, trees and sky, and its elements are designed so that their appearance and function are very close, as in the work of Hannes Meyer or authorless objects such as a boomerang. The floor lines of the Gallery show that they are the same as those of the 19th century building next to it, and the ground storey repeats its arrangement of a shop window and entrance door that has no relationship to the facade above. In the Gallery the first-floor window, the solid hatch above and the panel in the roof storey establish an axis that reduces the apparent width of the facade of the Gallery to make it seem closer to the width of the building next to it.

To connect with the earlier Lisson building the ground floor gallery is lower than the street. The effect is to make the space feel partly enclosed and for people passing in the street to look into the space over the heads of those inside. In the second and third floors the building looks in the opposite direction to the back lands of the immediate neighbourhood and shows that as the city changes much of it remains and is modified. The generality of the plan in these floors allows them to be rearranged from one type of apartment to another, from an apartment to a workplace, from a workplace to an office, from an office to an apartment and from an apartment to another type of apartment.

The spaces and fabric of the building are completed by what is outside them, and in turn create public and personal spaces from the rudiments of human behaviour.

This text was first published in Tony Fretton: Conversacion Con = Conversation With David Turnbull (Barcelona, Editorial Gustavo Gili: 1995). A selection of drawings of Tony Fretton’s Lisson Galleries in London from the Drawing Matter Collection is currently exhibited in Soane and Modernism: Make it New at Sir John Soane’s Museum.