Living Landscapes: Narrative Maps from The John Rylands Library

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail.

– Oscar Wilde, The Soul of a Man Under Socialism (1891)

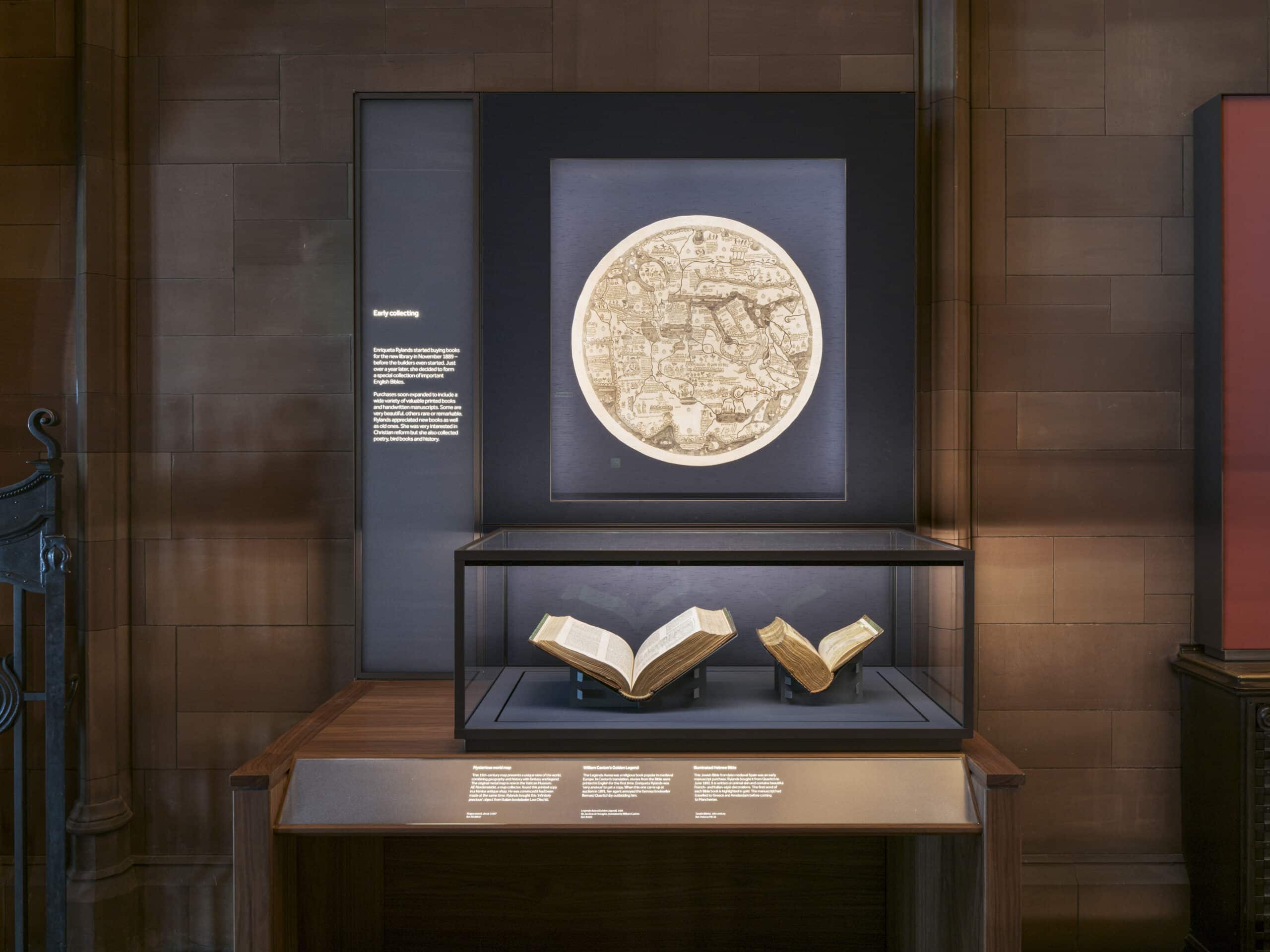

I have been fortunate enough to have been part of the design team at Donald Insall Associates making a series of creative alterations to The John Rylands Library, Manchester’s neo-gothic centrepiece. Now complete, two exceptional gallery spaces allow some of the rarest items in the University of Manchester’s world-class special collections finally to be brought out of the archives and shown to the public.

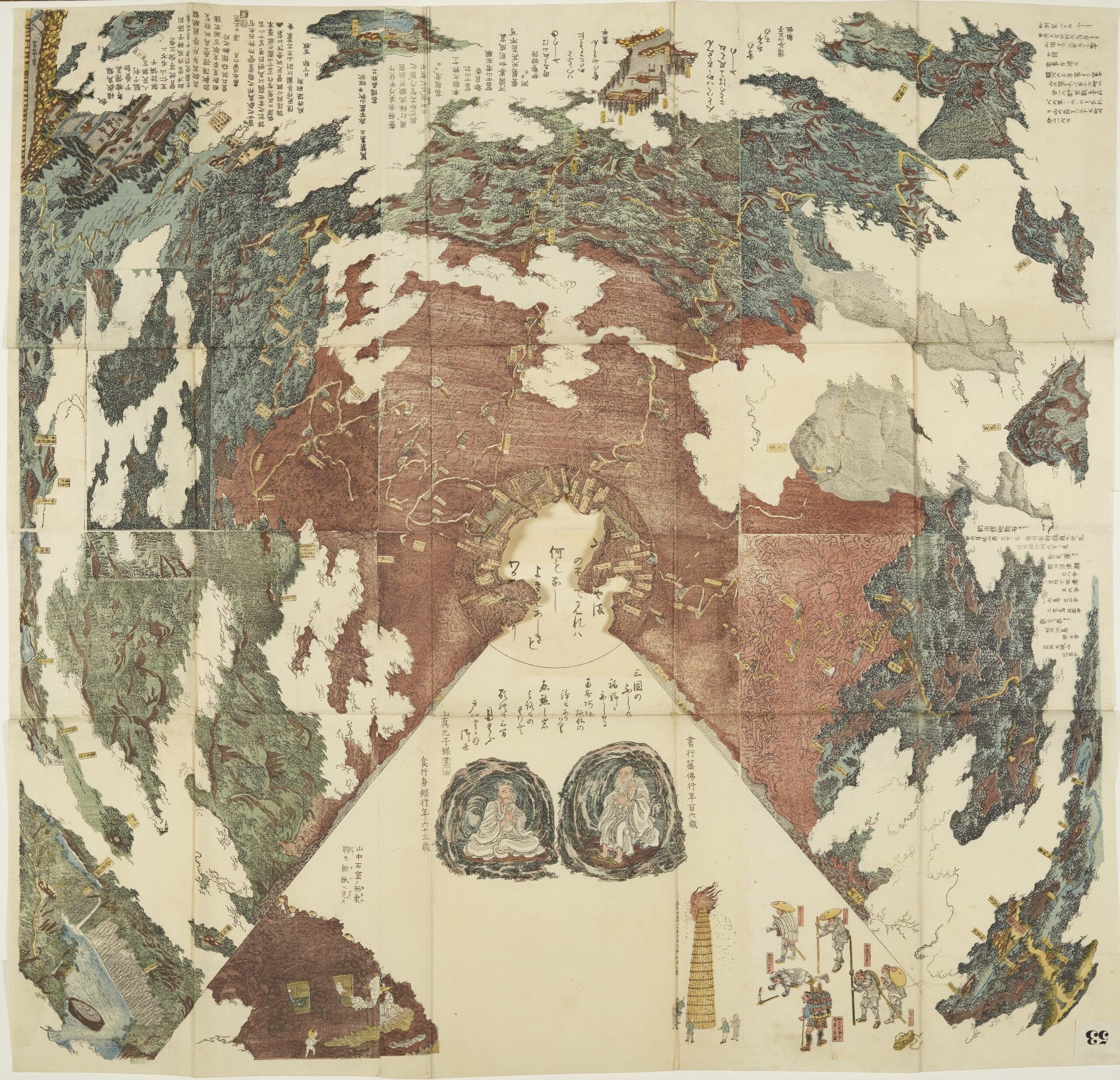

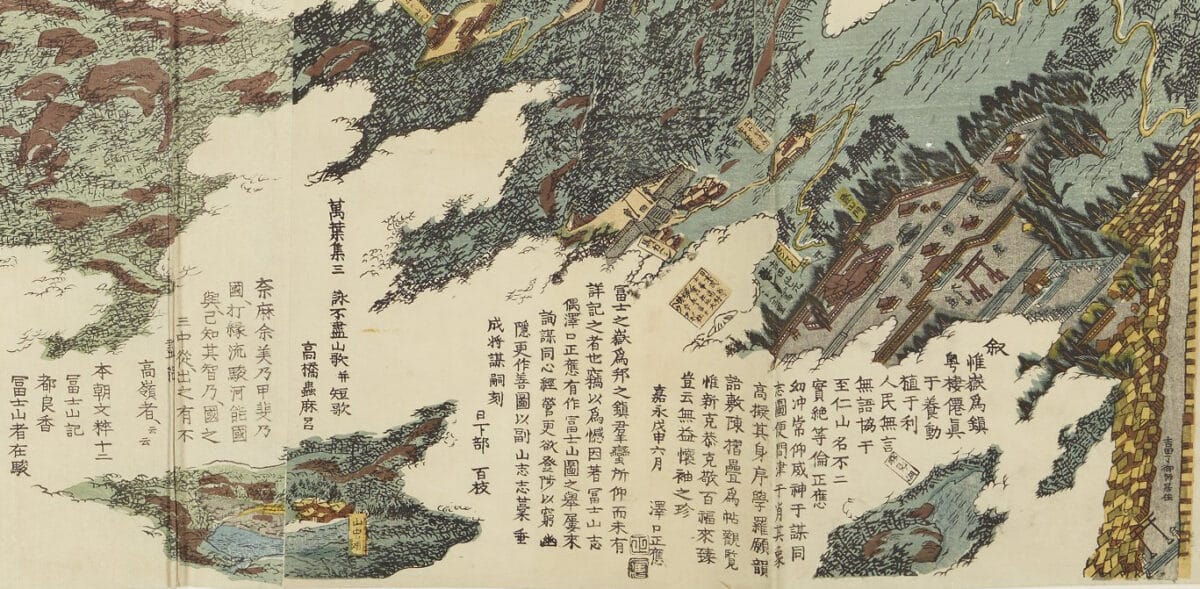

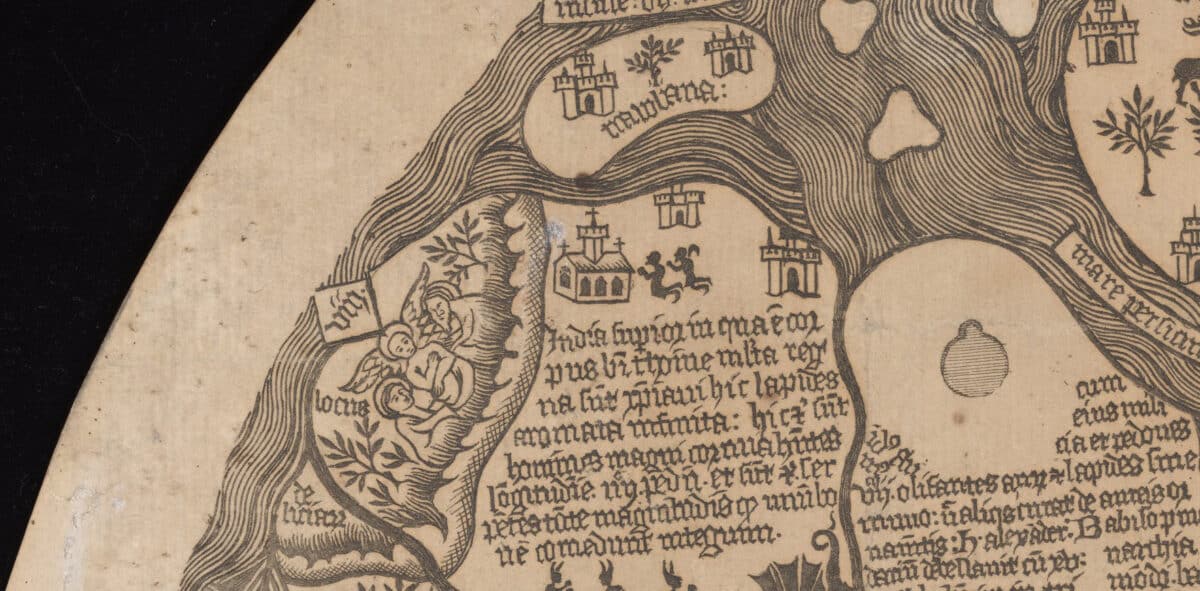

Front and centre sit two maps authored thousands of miles and hundreds of years apart: the Complete Map of the True Shape of Mount Fuji (1848) and a copy of a mappa mundi known as The Borgia or Velletri World Map dating from the 15th century (likely the 1430s, but this is hotly debated).[1] The map of Mount Fuji was commissioned by and distributed from a shrine on the northern side of the mountain. It is essentially a tourist map, complete with pilgrimage routes, locations of shrines, and tales of tradition and legend.[2] The mappa mundi similarly combines geography and history with legend and fantasy but over an image of the ‘entire world’, as understood by its European author. The copy in The John Rylands Library was made from an engraved copper version acquired by Cardinal Stefano Borgia in 1794 for his museum in Velletri.

The representational approaches of the maps are worlds apart. The mappa mundi has the effect of a woodcut, complete with bold monochrome characters and thick text, sometimes wedged awkwardly into the footprint of the country it is describing. The Mount Fuji map is something more ethereal, reading more like a delicate ink abstract than a map. Its author, the artist Hashimoto Sadahide, was known as the ‘flying painter’ for his love of aerial views.

At their core, both objects hold the aspiration that a map should do much more than provide geographical facts. They overlay recorded history, myths, cultural archetypes, instructions and, in some cases, outrageous claims—if you’ve ever wanted to know the exact location of both Noah’s Ark and the Garden of Eden, read on…

Writing on the shift from medieval to modern maps, the architect Bárbara Maçães Costa makes the point that:

Maps are visual tools for thinking about the world at many scales. They shape scientific hypotheses, organize political and military power, delineate private property, and reflect mental conceptions about landscapes and nonhuman nature. In the Western tradition, medieval maps were less territorial descriptions than conceptual cosmologies […] With the advent of modernity, an important shift took place. […] Accurate maps—stripped of all elements of fantasy, religious belief, and authorship—became essential tools for modern scholars and states who sought rational progress through scientific prediction, social engineering, and planning.[3]

These maps are a celebration of that pre-modern idea, allowing accuracy to give way to narrative flourishes. To more easily compare the wealth of narrative these drawings provide, the broad themes they present could be grouped into ‘activity’, ‘stories’ and ‘values’.

Map of Mount Fuji

Activity: A traveller in need of a guide would find relief in the clearly marked pilgrimage routes, temples, statues, shrines and meditation caves across this map. They might find comfort in knowing that something geological and impermeable has been transformed into a village of innumerable dwelling spaces—inhabited and alive. Straight lines march directly up the landscape, marking the vertical routes established to aid the ambitious hiker. Weaving paths criss-cross to define the horizontal routes for those in search of a more meditative journey. Along the way our pilgrim will be confronted by finely drawn figures in the midst of a festival or a prayer. They are not alone on their journey.

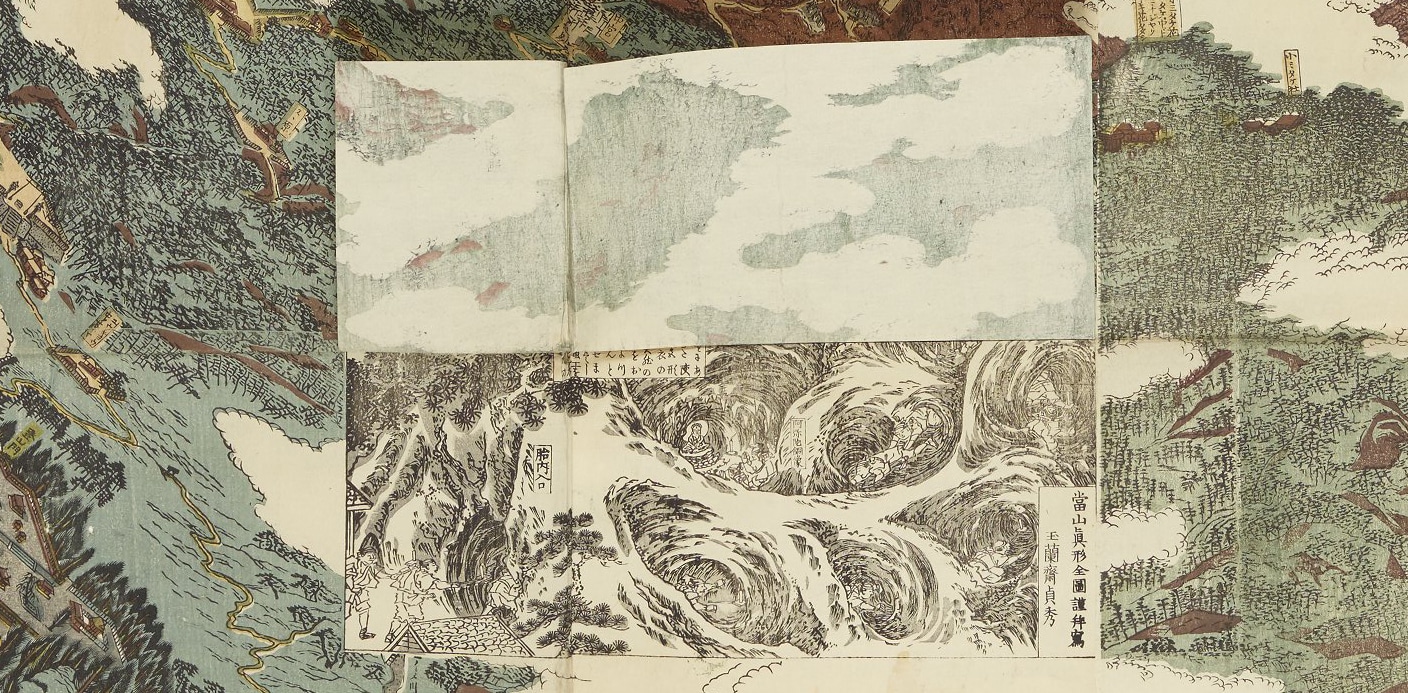

Stories: To the educated map-reader, not all caves represented are equal. Coming across the Tainai cave, a devoted pilgrim would stop to show their respects. Translated as ‘womb’, it is believed to be the birthplace of Sengen, the god of Mount Fuji. To those wishing to connect with this landscape, this map is more than a simple list of tourist hotspots—it can take you straight to the spirit of the mountain.

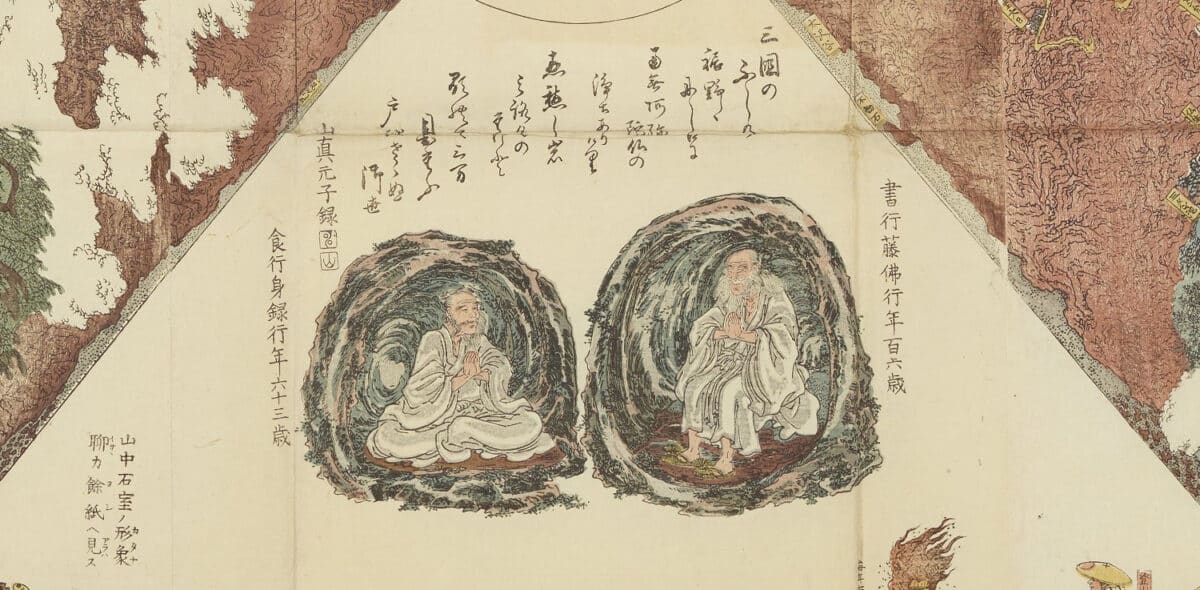

Values: Overseeing our pilgrim’s journey, two figures can be found painted in the open air aside the mountain. Famous mountain ascetics, Kakugyō Tōbutsuand his successor Jikigyō Mirokuare are given the highest prominence in honour of their contribution to the growth of the mountain’s following. The latter is known for fasting himself to death at the Eboshi-iwa rock, a sacrifice intended to give relief to others. Their position overseeing those ascending the mountain shows what value is given to the people who dedicated their lives to the spiritual relief of others.

Mappa Mundi

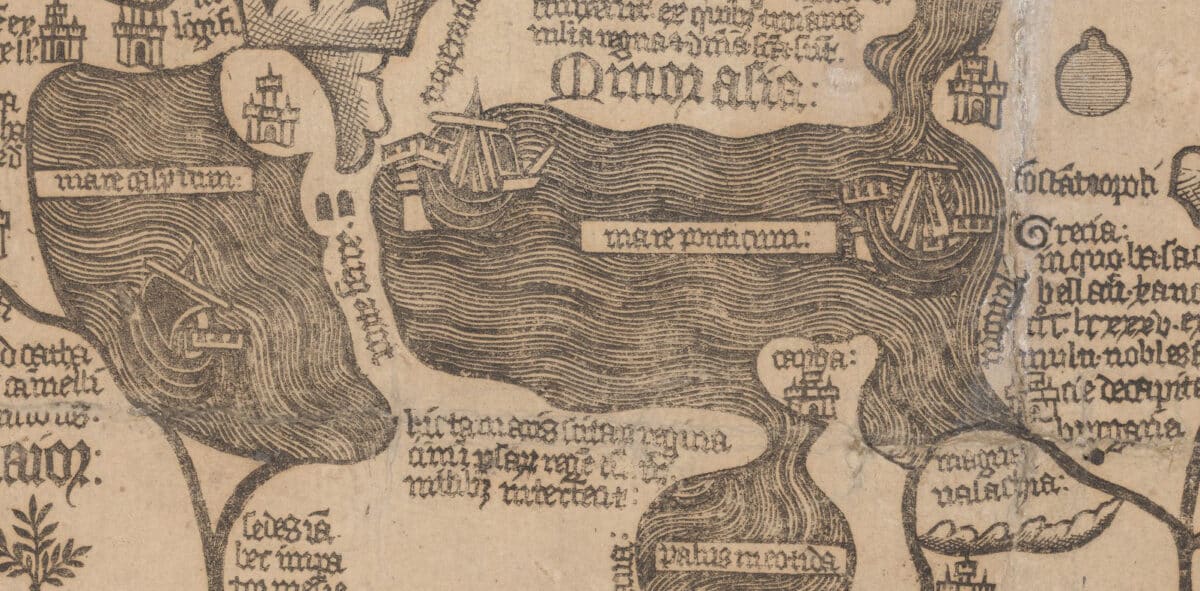

Activity: In this volatile world, you are never more than a step away from the heroic, uplifting or outright dangerous outcomes of human action. In just a few steps you will stumble across military campaigns and religious revolutions. A few more steps and you are in the sanctuary of the silk forests of China or the fertile farms of Italy. The human capacity to tear the world apart is shown side by side with its capacity to care.

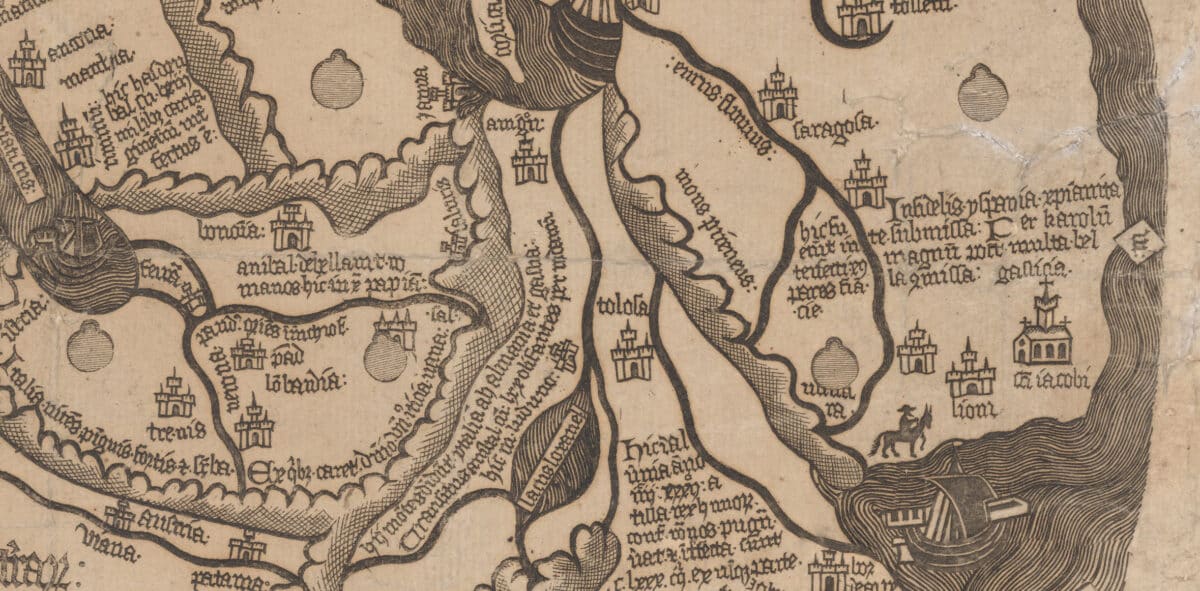

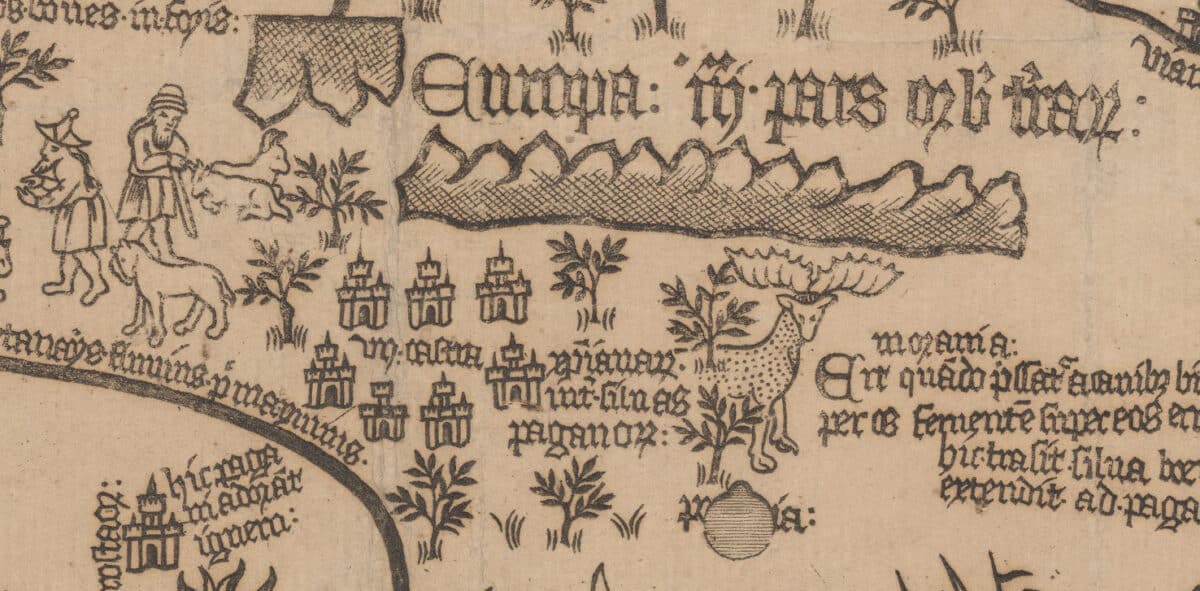

Stories: Traversing this landscape, where myth and history are interwoven, is not for the faint-hearted. Here you are just as likely to be trampled by Hannibal’s Pyrenees-crossing elephants as you are burned to a crisp by the mythical deer vomiting boiling water. Likewise, you are just as likely to find the remnants of Charlemagne’s Spanish Campaign as you are the moored remains of Noah’s Ark (in Armenia, in case you were wondering). For those willing to cross to the very edges of the known world, you will be rewarded with none other than The Garden of Eden (just off the east coast of India, to be precise).

Values: Perhaps the most useful lesson for today’s viewer: a reminder of the shifting sands of what is given ‘value’. Here in ink lies evidence that what we see as timeless today may be seen as insignificant in the not-so-distant future—just as it was seen as insignificant but a few hundred years ago. One example, in this 15th-century snapshot where historic events, legends and heroes spill over the borders of almost every country, there isn’t a single line of information associated with merry England, which would go on to write a very different history for itself not long after. And that’s not to even mention the complete lack of any lands America-shaped.

Taking a step back and leaving the detail behind, the feeling that resonates after spending time with these drawings is that they have both infused space with human interaction. I should say ‘life’s interaction’ not ‘human interaction’ as the silk trees of China and the monsters of central Europe have as much value in these maps as any human being.

There is an excitement to this representation. That the world we inhabit might come to life as we interact with it. This is a relationship.

This engaging worldview is a testament to the philosophy of the cultures that authored these works, but also to the skills and vision of the artists behind these living landscapes. The work of human hands, representing human interaction, results in something very much alive. The Mount Fuji map takes this brief as far as possible, as flaps open to reveal hidden drawings behind, and it even (amazingly) is designed to fold up into a model of the mountain. As well as wanting you to interact with the mountain, it even wants you to interact with the map!

As simple an observation as this is, there is something universal here that explains why these maps still speak to us centuries on.

Seeing the world as an entity to have a relationship with, rather than a static object, brings to mind two phrases: ‘in the world’ vs ‘on the planet’. These might be used interchangeably in casual conversation, but looking closer they contain completely different principles.

To be ‘in the world’ is to see the world as an ocean or a forest, to explore and nestle into. It’s amorphous and has no formal edge. The immediate elements that surround you are all that matter, and if you respect or disrespect them it directly affects your life experience. To be ‘on the planet’ however is to see the world as a rocky sphere, to sit on top of and look out. There’s a definite edge and you can sit outside of it, with your actions possibly bouncing off it and into the ether.

These two maps are the former. They are phenomenological atlases, portraying the world as a place to sink into, form a relationship with and bring to life. The outcomes of your ancestor’s relationship with the world have defined your life. These maps then ask you how you will interact with your world, what actions/ stories/ values you will bring to this place and leave for the next generation. Or, if you have an impact as long-lasting as the mappa mundi, for the next ten generations.

Rory Chisholm is an architect and Associate Director at Donald Insall Associates. He is also an Associate Member of the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts. He discusses his own drawings here on Drawing Matter.

The John Rylands Library ‘Next Chapter project’ was completed in May 2025, focusing on new gallery spaces to allow better public access to the Rylands’ special collections. It was a collaboration between architects Donald Insall Associates and exhibition designers Nissen Richards Studio, for the University of Manchester. Further information can be found in the Architect’s Journal.

Notes

- Matthew Edney, ‘Materiality and the Limits of Internet Research: The ‘Borgia Map’ and its Facsimiles, Mapping as Process, 26 February 2025 <https://www.mappingasprocess.net/blog/2025/2/26/materiality-and-the-limits-of-internet-research-the-borgia-map-and-its-facsimiles> [Accessed 14 July 2025].

- University of Manchester Digital Collections: Fujisan shinkei zenzu (Japanese 70), description available at https://www.digitalcollections.manchester.ac.uk/view/PR-JAPANESE-00070/1. [Accessed 14 July 2025].

- Bárbara Maçães Costa, Cartography <https://barbaramacaescosta.info/cartography> [accessed 14 July 2025].

– Fernanda Canales