Manufacturers Trust Bank

When one thinks of Manufacturers Trust Company and New York City architecture, the first image that comes to mind is Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill’s international style bank building on Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street from 1954. By that year, SOM with Gordon Bunshaft as a design partner were the architects of two international style buildings, the other being Lever House on Park Avenue and 53rd Street, which helped place New York City in the forefront of post-war architecture. Both buildings were designated New York City landmarks, Lever House in 1982 and Manufacturers Trust in 1997.

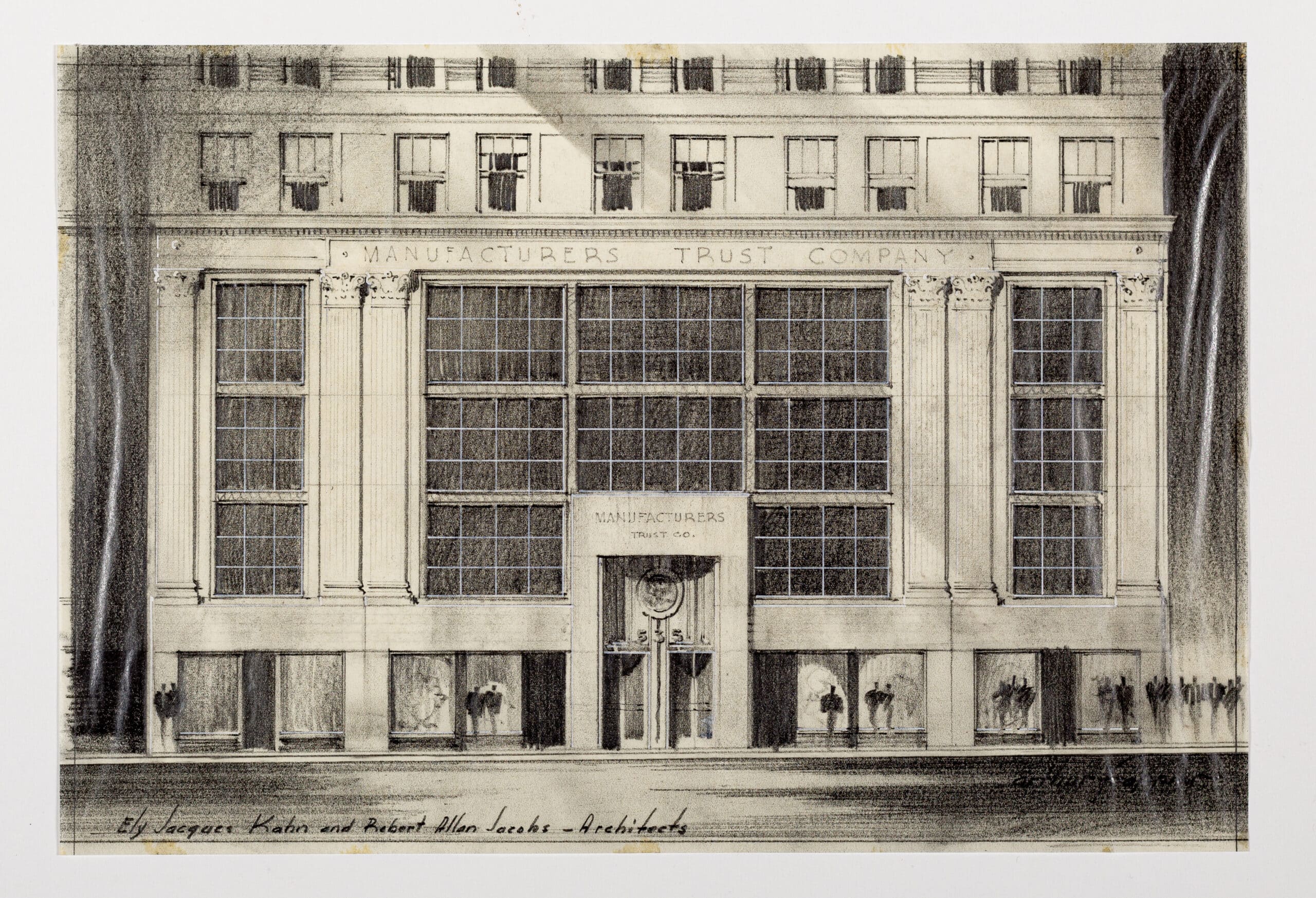

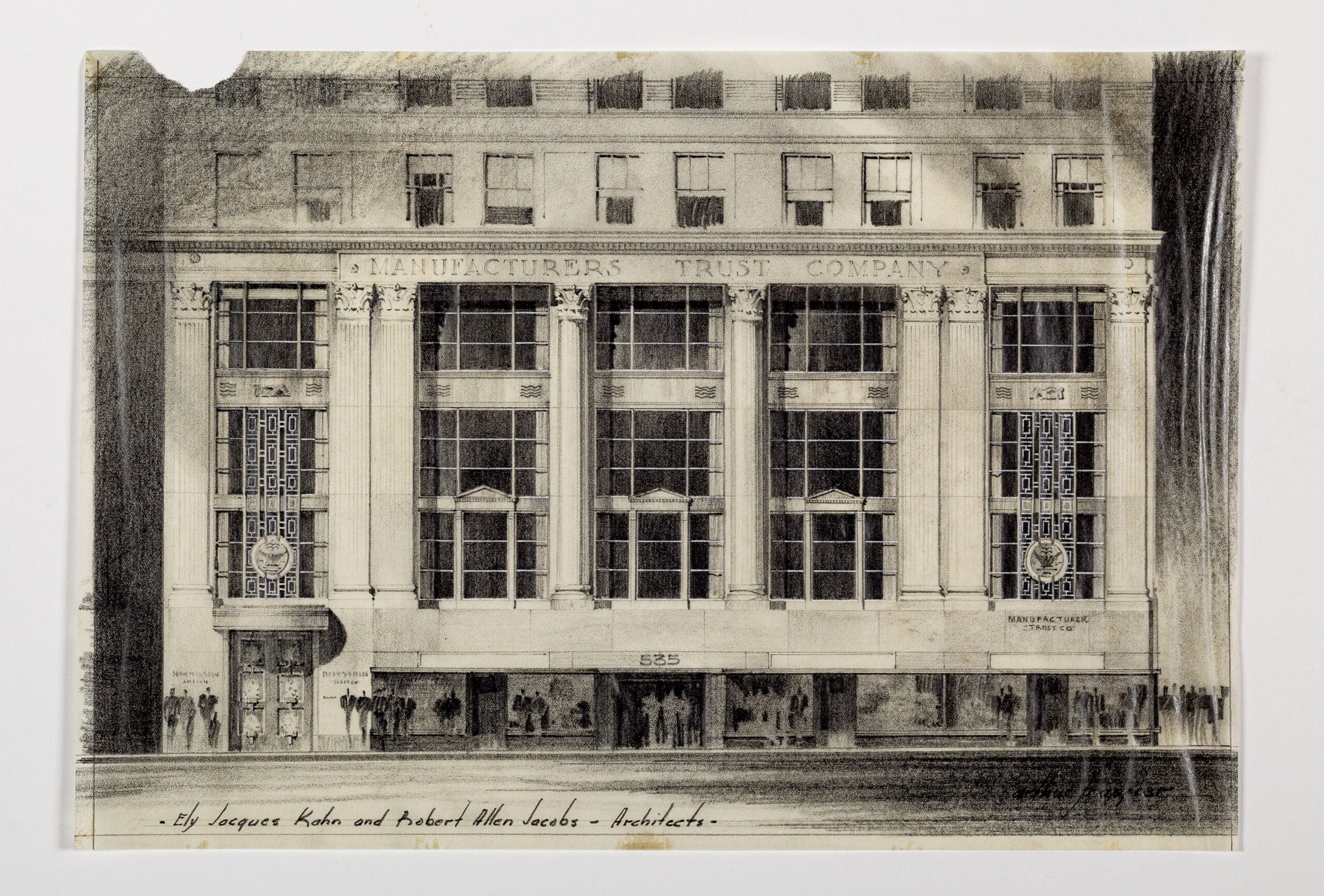

These four drawings—one by Godwin, Thompson, and Patterson and three by Ely Jacques Kahn and Robert Allan Jacobs—look like they belong to a different era of bank building, when brick and mortar architecture meant the security of one’s money. So how did Manufacturers Trust Company come to build a transparent bank building that quickly became its most popular branch and a tourist destination as well? The answer to that can be found in the very detailed designation report researched and written by Matt Postal for the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.[1]

The origin of Manufacturers Trust Company can be traced to 1853 in Brooklyn and by the 1920s, it was one of New York City’s largest banks. In 1925, the bank opened a branch at 511 Fifth Avenue in the Postal Life Insurance building (York and Sawyer, 1915), which soon became the second largest in their system. Even during the Depression, that branch continued to open new accounts and soon they were operating at capacity. In 1941, the bank began to consider commissioning a new building, with their eyes set on the site directly across the street. It took several years to negotiate the leasing, zoning requirements (the new building could not be taller than the 68-foot-high structure it was replacing), materials for construction, and approval from bank regulators to move the bank. Finally, in 1944, the bank hired Walker and Gillette to design a new bank building. There are more wrinkles to this commission, which went on long enough for the winds of architectural design to change and for SOM to convince the bank it would be cheaper to begin with a fresh design.[2]

So how do these four drawings fit into this story? Only one of them has a date on it: 1941, penciled in the lower right corner of the rendering from Godwin, Thompson, and Patterson. A street number is given on two drawings from Kahn and Jacobs, ‘535’, but not the avenue. Given the amount of street traffic and the commercial stores, it is most likely an avenue and not a cross street. A search of that address on different avenues confirms the location as 535 Fifth Avenue at 44th Street, one block north of the bank branch at 511 Fifth Avenue.[3]

The building at 535 Fifth Avenue and 44th Street was constructed in 1927 as Fifth Avenue was becoming more commercial.[4] Until the 1920s, the area just above 42nd had been largely residential and included several significant religious buildings on their initial sites, such as Temple Emmanuel (Leopold Eidlitz and Henry Fernbach, 1868) and St. Bartholomew’s Church (Renwick & Sands, 1872–1876) before they moved uptown to their current locations. 1927 also saw the construction on the northeast corner of 45th Street of the Fred R. French Building, by Sloan and Robertson in a colourful Deco style that still makes a strong statement on Fifth Avenue. The corner of Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street was considered the second most valuable real estate location in Manhattan, the first being the corner of Broadway and Wall Street opposite Trinity Church. 500 Fifth Avenue, built in 1929–1931, was designed by Shreve Lamb and Harmon, a successor firm of Carrère and Hastings who had designed the New York Public Library main building just across the intersection. At the same time, Shreve Lamb and Harmon designed the Empire State Building at 34th and Fifth Avenue. One block north of 42nd Street, that firm also designed 521 Fifth Avenue on the former site of Temple Emmanuel which moved uptown to 65th and Fifth Avenue.

No wonder, with all this office building construction and the workers and businesses they brought, that the branch bank at 511 Fifth Avenue continued to open new accounts.

The firm of Godwin, Thompson and Patterson was very active in New York. They had recently designed one of the demonstration houses for the Johns-Manville’s ‘House of Tomorrow’ at the 1939 New York World’s Fair[5]. Ely Jacques Kahn (1884–1972), the architect of the other three drawings, had been a practising architect for more than 30 years and in the building boom of the 1920s, was considered, along with Raymond Hood and Ralph Walker, one of the leaders of New York City architecture. Kahn was known for his well-planned, office buildings that provided flexible floor plans, found throughout the city and particularly in the Garment District. A decade later, after the economic depression and with growing political tension in Europe, building supplies were very limited and construction, particularly of new buildings, had ground to a halt. In his diary on 1 October 1939, Kahn wrote that ‘work [had] never [been] so dull’ and the ‘[w]ar in Europe has construction demoralized—at least as far as I’m concerned. What’s ahead [is] a pure guess.’[6]

But now, two years later, with war raging in Europe, what was happening in New York? In this case, perhaps what was available at the moment right before the United States entered the war, were commercial remodelling jobs like the project shown in these drawings. It seems possible that the bank, facing the same monetary and construction issues that architectural firms did, thought that moving to a new location up the street might ease or solve their capacity issues. With the zoning and regulatory issues involved in moving to the other side of the street, the commercial space imagined by these drawings might have been an initial attempt at alleviating their problems. But moving from 511 Fifth Avenue, which had been built as a bank, might have been more costly than imagined. The bank may have discovered that that was not cheaper nor satisfactory at all once the interior specifications for bank vaults and security were factored into the project.

Kahn noted in his diary on 9 October 1941 that his firm’s future was ‘touch and go.’ His offer of partnership to the younger Robert Allan Jacobs (1905–1988) in 1940 came with the usual expectation that the new partner would bring clients to the firm. At first, Kahn offered Jacobs just a 15% partnership. It was not until December 1941 that a 50% partnership was finalised—at the insistence of Jacobs. The use of the full names of the two partners in these drawings is odd. All sets of project drawings at the Avery Library Drawings and Archives show Kahn & Jacobs in the title blocks. Why the use of the full names instead of the partnership? As a newly renamed firm, perhaps Kahn wanted his name in full to let potential clients know it was him, a transition from the Ely Jacques Kahn Architects of the 1930s moving into a new partnership. Maybe it revealed some of the tensions of the new partnership. Ultimately, the partnership between Kahn and Jacobs was not a congenial one, however successful it eventually was professionally.[7]

In 1940, the renderer Arthur Frappier returned to work for Kahn and now Jacobs after a brief turn in another firm. While architects are not known to be accurate spellers on their drawings, the renderer did not apparently confirm the spelling of the new junior partner’s middle name, not once but three times. Frappier was born in Rhode Island in 1899, went to the MIT School of Architecture in the mid-1920s, came to New York in the building boom of the 1920s, and then during the Depression moved around for work. He had been in Ely Jacques Kahn’s firm before, working on the Pix Theater on 42nd Street in 1939; of the 72 working drawings for this theatre in the Kahn & Jacobs collection at Avery Library, 53 are initialled ‘A.F’.[8]. Frappier appears to have remained with the firm for the rest of his career and was project manager under Kahn for 425 Park. Frappier continued to provide renderings for other projects, such as Kahn’s ‘Ideal Housing’ of 1941 and an alternate rendering for a multi-purpose building at Broadway and 45th-46th Street.[9]

The three drawings by Frappier are of two distinct styles. The pencil drawing, with green and orange colour touches, refers back to a drawing style the Kahn firm used in the 1920s. A drawing for Kahn’s Lefcourt Clothing Center of 1927 on Seventh Avenue shows how this media was used for those projects. This drawing matches the style of the detailed, strong pencil lines of the Godwin, Thompson, and Patterson rendering. Both designs retain the colonnade above the entrance and the fenestration, adding elements to bring more attention to the commercial front. The two heavy pencil drawings, showing direct homage to Hugh Ferriss’ urban vision of the city as a nighttime space, open up and enlarge the fenestration and minimise the columns and pilasters. The ground floor storefronts are streamlined, smooth facings, with large windows, that would not have been out of place at Rockefeller Center. For that time, these were forward-looking designs.

But for these drawings, the very beginning of the development of the 1954 Manufacturers Trust Building would have been lost. From Kahn & Jacobs and Godwin, Thompson, & Patterson to Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill—what a difference a decade makes.

Now, seven decades later in 2024…

Notes

- The designation report containing updates by Matt Postal for Manufacturers Bank can be found here: 2467.pdf (nyc.gov).

- Postal, 1–2.

- A building on 7th Avenue at that address is similar to this one, but differs in the spacing of the windows. The five pairs of windows are spaced a little further apart on Seventh Avenue whereas the stronger vertical façade element on Fifth Avenue emphasises the pairing of the windows. And only at 535 Fifth is there a continuation of the facade details into the building at its left. The first two drawings with classical details show the building on the left, as in this current photo. The two buildings, now numbered together as 531–537 Fifth Avenue share the present commercial storefront facade, which continues around the corner on the 44th Street front.

- See image of 5th Ave north of 42nd Street, towers of Temple Emmanuel on the right: Museum of the City of New York – [5th Avenue north from 42nd Street.] (mcny.org).

- Architectural Adaptations: Silver Spring’s 1939 World’s Fair Home [Updated] | History Sidebar (historian4hire.net)

- Jewel Stern and John A. Stuart, Ely Jacques Kahn, Architect: Beaux-Arts to Modernism in New York (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006), 194.

- Stern and Stuart, 196–197. Robert Allan Jacobs, the son of architect Harry Allan Jacobs, was a Columbia graduate like Kahn and had worked for Le Corbusier in Paris in the 1930s before returning to New York. He worked for Harrison & Fouilhoux until the completion of the 1939 World’s Fair and was laid off. Max Abramovitz, Harrison’s future partner, was then in the US Navy. Jacobs then remembered a job offer Kahn had made to him recently.

- In the Avery Drawings and Archives: https://clio.columbia.edu/catalog/3462648. A smaller movie theatre, the Pix was designed to show foreign films, but its life ended as the last peep show on 42nd Street before that area was demolished in 2006 and redeveloped as the Bank of America tower. New York City had a number of smaller movie theatres like that. The Paris Theater, next to the Plaza Hotel and designed after WWII, escaped the wrecking ball after Netflix refreshed the interiors and began to show movies there again.

- Stern and Stuart, Ely Jacques Kahn, Architect, 200 and 222.

Janet Parks is an independent historian specialising in architectural archives. In 2017, she retired as Curator of Drawings and Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University.