The Many Lives of the Open Hand

Le Corbusier, The Bhakra Nangal Dam & A Childhood in Chandigarh

Saturday afternoon, 4pm, the summer heat. My father revs up the engines of his Fiat 1100, his pride and joy. It is the early 1970s and I am in my pre-teens. Small for my age, I squeeze into the front seat, between my parents. I am not welcome in the rear. There my two sisters, both elder to me, divide the back seat, very, very evenly. Though it is state of the art technology for the time, the Fiat has no air-conditioning. So my father drives on the highway with the windows open. Wind blasting through our hair, as we squeal with delight. Our mother winces.

We are on our way to Pandoh, in Himachal Pradesh, one of the hilliest states of India carved into the Himalayas. Pandoh was the site of one of yet another of the hydro-electric dams built on the Beas and Sutlej river systems, the waters of which were accorded to India in the Partition of 1947. This meant that their waters had to be ‘used-up’ before they crossed the border into Pakistan, which meant that building dams on these river systems was one of the highest priorities of Jawaharlal Nehru. The first Prime Minister of independent India, Nehru was not only the undisputed head of the nation, he was also the conceptual fount of modern India. For Nehru, the hydro-electric dams were not just infrastructural projects: they were sacred opportunities to reinvent the symbolic apparatus of Indian society. Ambitiously he christened the dams the ‘temples of modern India’, hoping that the idea would stick. Somewhere in the back of his mind perhaps he thought that he might be remembered for these dams in the same way that Raja Rajeshwar is still recalled with awe for his construction of the mighty Rajarajeshwaram temple in Thanjavur, built a millennium prior.

To make sure that the dams didn’t remain ugly infrastructural behemoths, Nehru had invited Le Corbusier to advise on their architectural aesthetics; on their ‘beautification’, I think, was the actual term that was used, though I am not sure. Le Corbusier was in India a lot in the 1950s, working on the Chandigarh Capital Project, another one of Nehru’s big symbolic projects. Initially Nehru had not wanted to hire a foreign architect, simply because that would be too expensive. But then his bureaucrats convinced him otherwise; for a significantly small fee they could not only hire Le Corbusier, but also Pierre Jeanneret, Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry for the project. The prestige of the project made that possible. Nehru acceded and Jeanneret, Drew and Fry relocated to the Chandigarh site. Le Corbusier flew in twice a year.

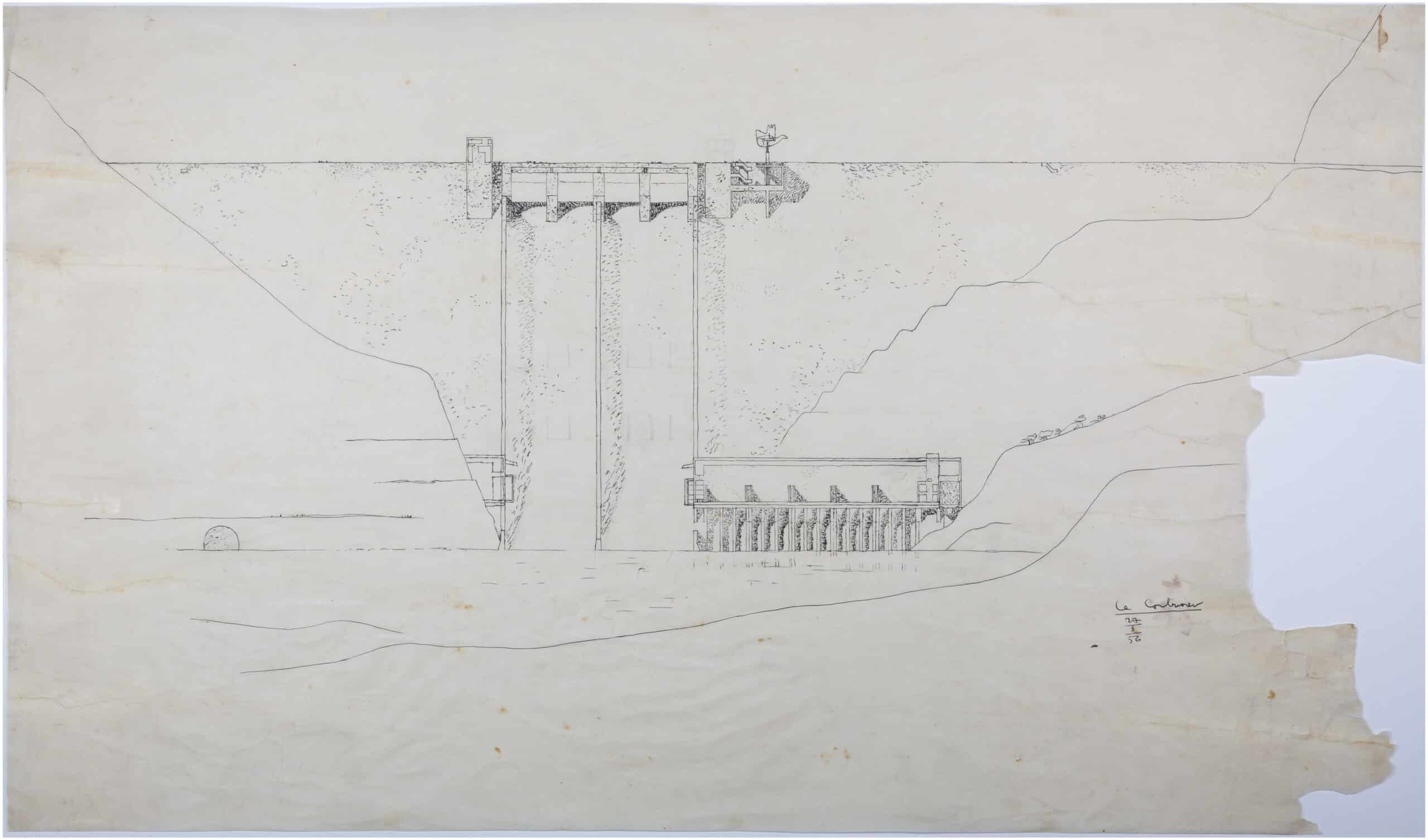

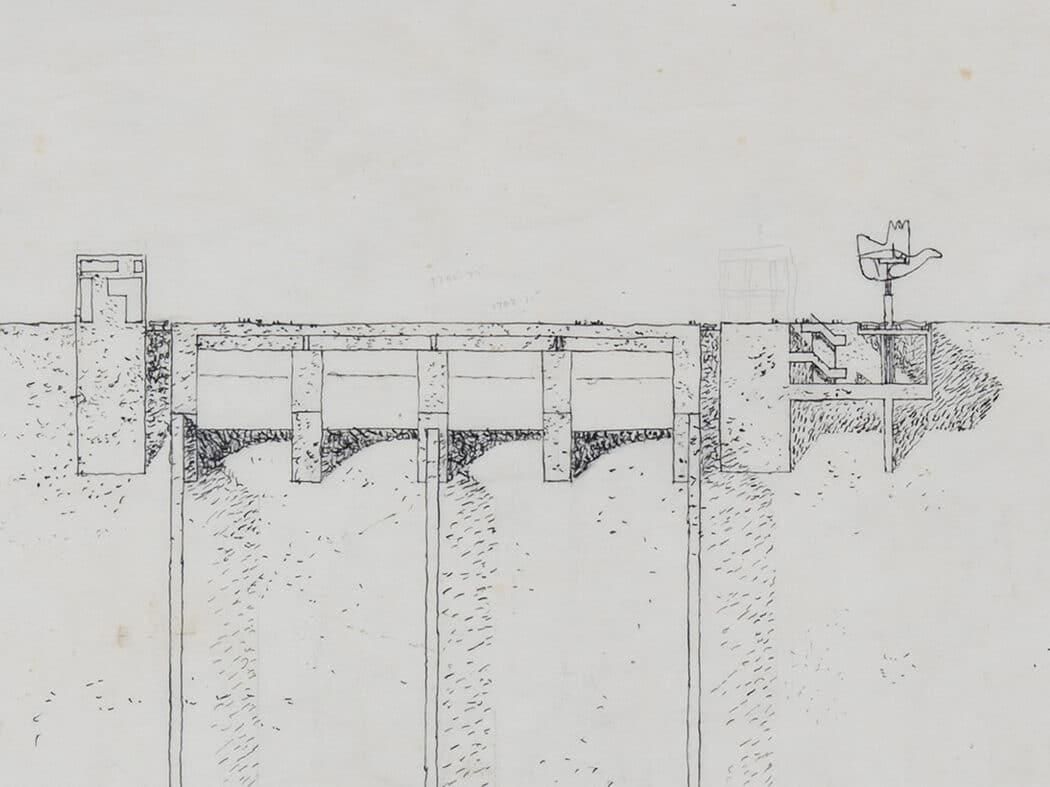

Once hired, Le Corbusier and Nehru became great friends. Both modern men cut from the same cloth, the heady combination of idealism and romanticism ran deep in both their bloodstreams. Le Corbusier immediately recognised the potential of thinking of dams as the ‘temple of modern India’. Large-scale architectural symbolism was Le Corbusier’s celebrated expertise. So, Nehru had invited him to propose ways in which Bhakra Nangal Dam, the star-dam in the Beas-Sutlej system, could be aestheticised.

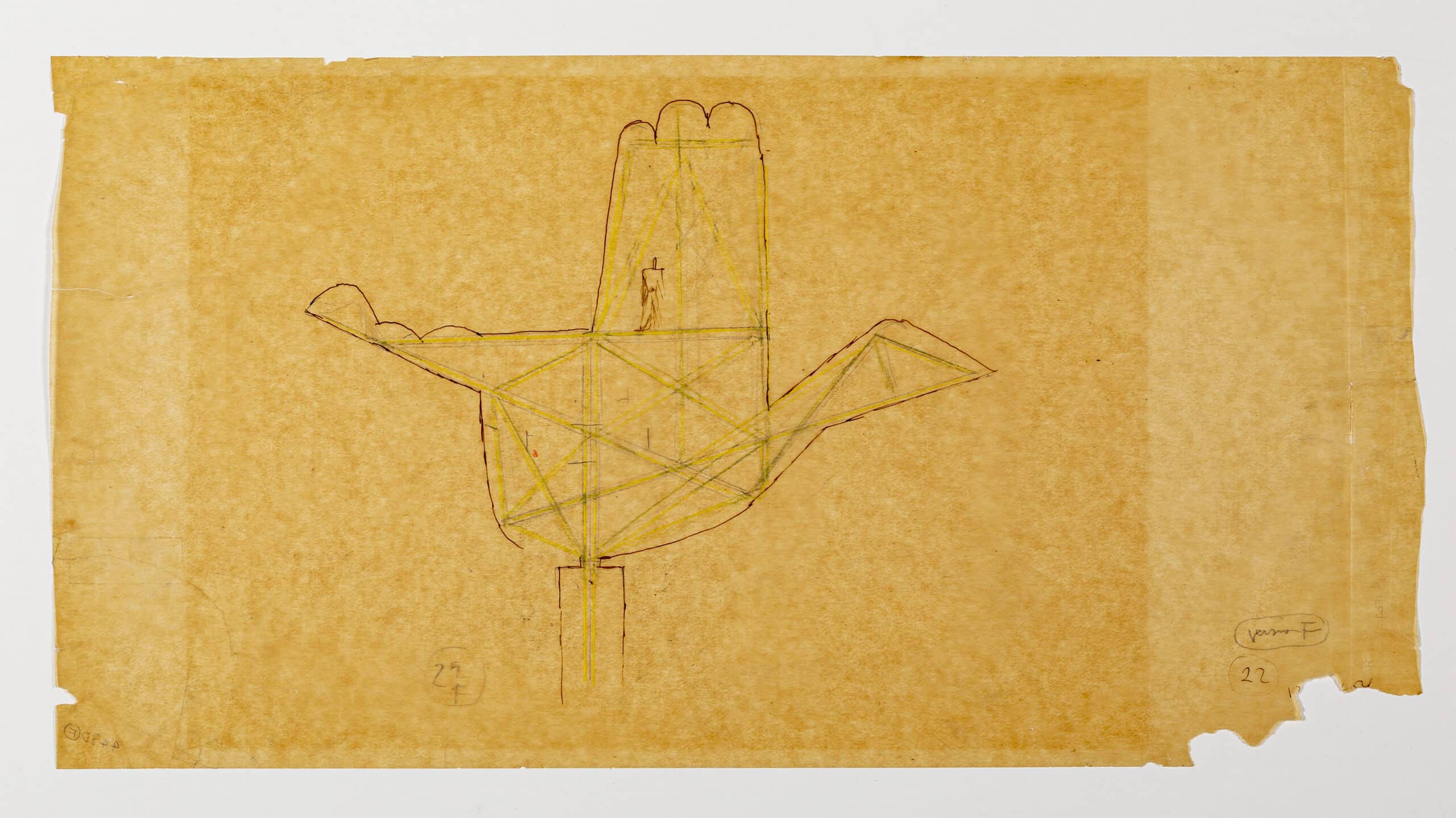

There are several photographs of Le Corbusier at the Bhakra Nangal site, smiling in front of the big dam under construction. He is always in a safari suit, with its big pockets bulging from all his coloured pencils, Swiss army knife, measuring tape, sketchbook, and such. On one of these visits he decided to plant a flag on top of the dam, the flag of Le Corbusier, the Open Hand.

In fact, Le Corbusier offered the Open Hand to Nehru as a gift, another heroic symbol on the global stage. In 1955 Nehru had led the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement that had turned away from the two-world bi-polar choices of the Cold War and insisted on remaining independent, autonomous. Le Corbusier was energised by this intervention into global politics by Nehru, and offered the Open Hand as a symbol of NAM. ‘They constantly put pressure on me too to join one side or the other. I have always also refused. The Open Hand is a symbol of that refusal, of independent thought.’

Le Corbusier was a Non-Aligned Modernist and the Open Hand was a testament to his faith, and of the faith he had in fellow modernists like Nehru in their vision of a better world to come. Nonetheless, Nehru did not find the budget to build the Hand on Bhakra, most likely because by the early 1960s his faith in NAM was shaken with the 1962 Chinese invasion of India.

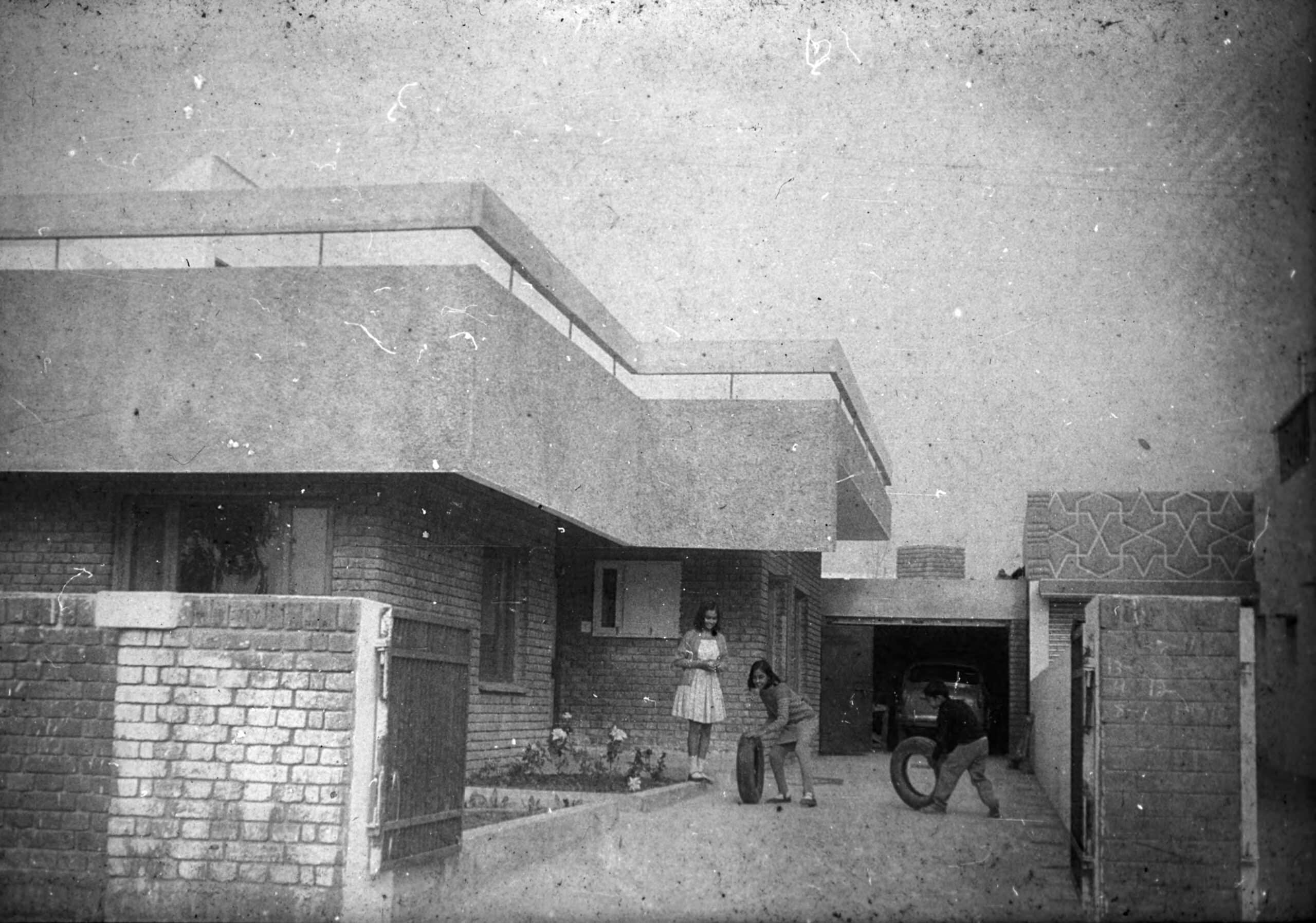

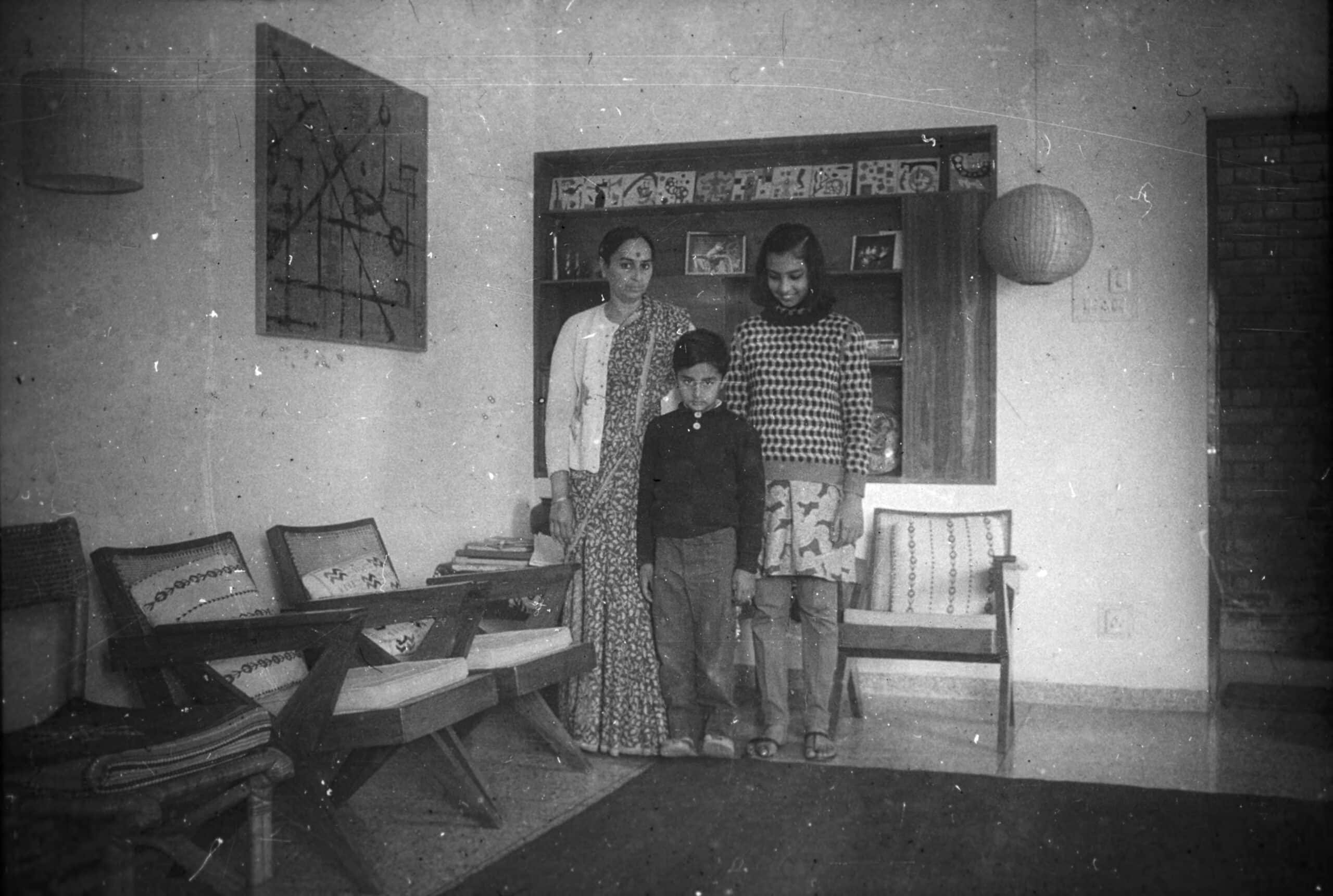

By the 1970s, both Nehru and Le Corbusier were dead. In the 1970s, a version of the Hand was finally constructed in Chandigarh, at the top of the Capitol Complex. The Open Hand became the symbol of Chandigarh and began to be printed on stationary. By then Bhakra was long since commissioned, and now all the smaller dams in the system were being built. My father, Aditya Prakash, had cut his teeth on the Chandigarh Capitol Project, and was now Dean of the local school of architecture. The task of ‘aestheticisation’ of the new dams was now passed down to him. One of the old bronze casts of the Hand occupied centre stage in our drawing room.

On our way to visit the dams, my father would tell us the story of how Le Corbusier had proposed the Hand for Bhakra but that Nehru had refused to have it built. He did not really know why, but he always remarked that there was a joke amongst the architects that the Bhakra Hand was designed as a traffic policeman’s stop sign, ordering the waters of the Sutlej to halt. I remember well how he would guffaw uncontrollably, as he told this story veering behind the wheel of his Fiat 1100. We didn’t really get it, but we squealed anyway. A trip to the dam was always a holiday, a family picnic.

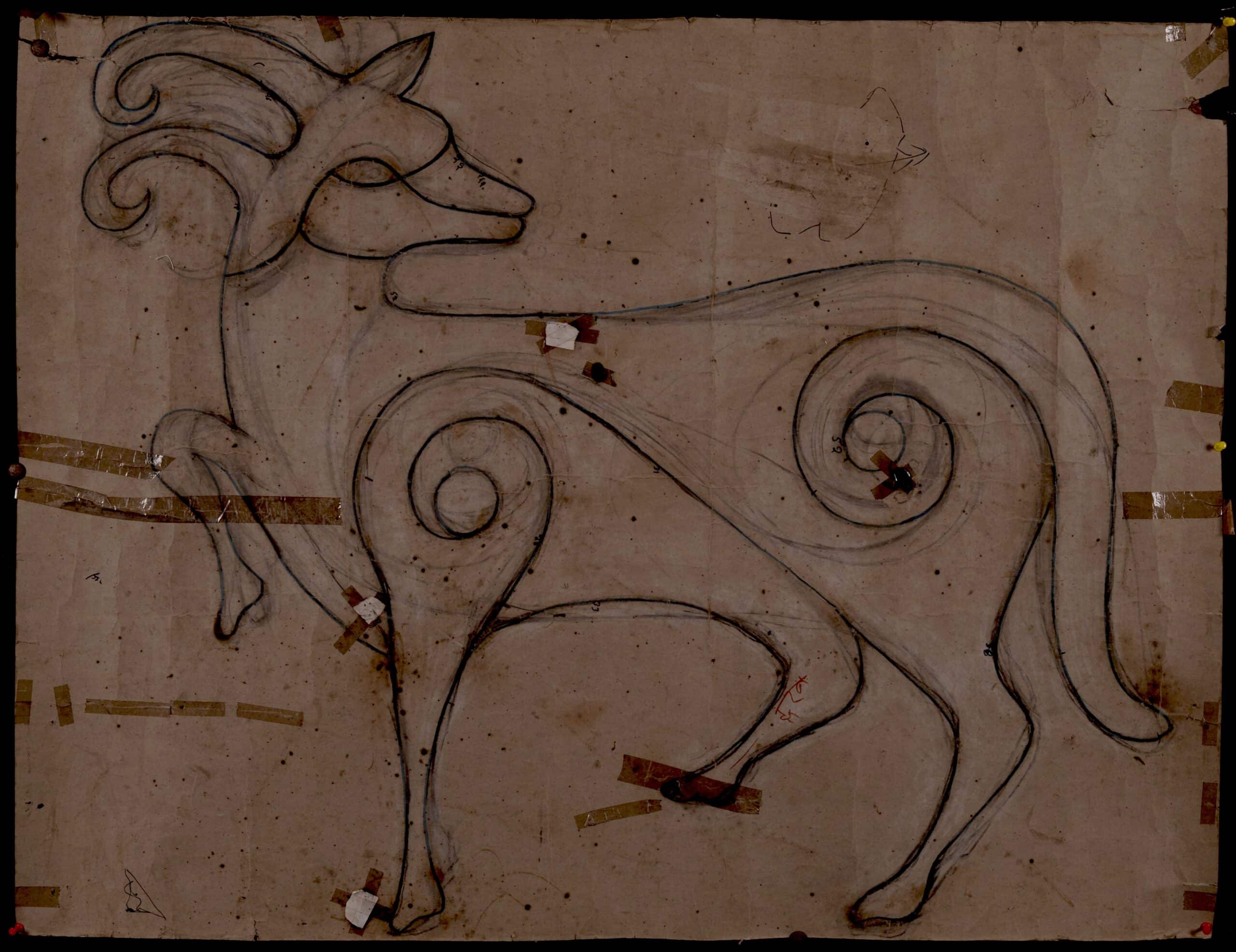

Now that it was his turn to officiate as the architect of the dams, my father had his own ideas about forms that could adorn the concrete of the dams. He proposed birds and animals, all drawn in his one continuous line characteristic style. If the Le Corbusier-Nehru vision was focused on global peace, his was invested in equity between humans and animals, urban and rural. He built beautiful metal mock-ups to illustrate his creations. None of these were built at the scale he wanted either. Budgetary reasons masquerading for loss of vision, I believe.

Dr Vikramaditya ‘Vikram’ Prakash is an architect, architectural historian and theorist. He is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington with Adjunct appointments in Landscape Architecture, in Urban Design and Planning and in Digital Arts and Experimental Media. He is also a Member of the South Asia Programme in the Jackson School of International Studies. His recent publications include Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh Revisited: Architecture as Future Preservation and One Continuous Line: Art, Architecture and Urbanism of Aditya Prakash. His first novel entitled Death of a Modernist is due to be published in early 2026.

– Niall Hobhouse