Sant’Elia and Global Futurist Architecture

‘Found’ in the archive at Drawing Matter, this wild text by Marinetti on his friend and collaborator Sant’Elia seems not to have been previously translated. Its occasion was a commemorative exhibition of the young architect’s work organized in 1930 by the commune of his native city, Como, fourteen years after his death in the defence of Montefalcone.

Filippo Thomaso Marinetti (1876—1944) and Antonio Sant’Elia (1888—1916), Mostra delle opere dell’architetto futurisa comasco Sant’Elia Catalogue 1930. Print on paper, 170 x 123 mm. DMC 3037.

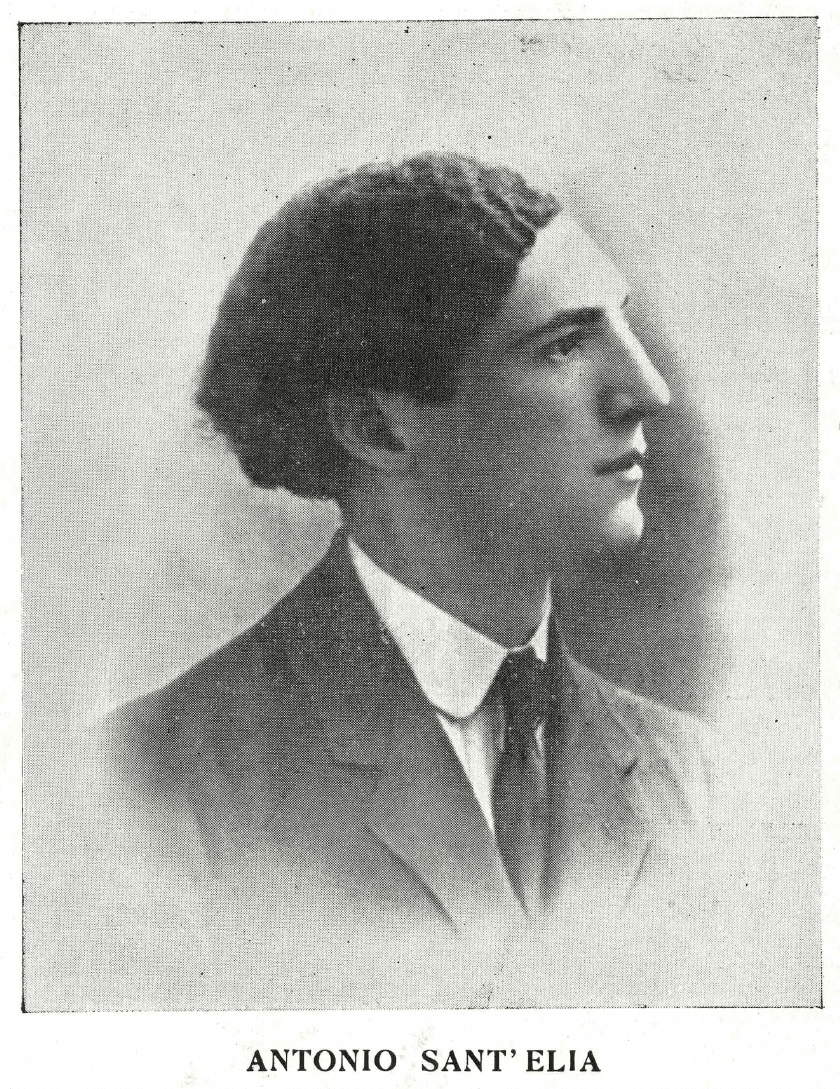

Born in Como on 30 April 1888 (Antonio Sant’Elia) to Luigi Sant’Elia from Como and Cristina Panzilla from Caserta (Naples). He studies in Como, first at technical schools then at the Scuola Castellini. A master builder at the age of 17 in Milan, working on the Villoresi Canal, then for the municipality. He enrols in the Accademia of Brera, following its courses and taking the exams of an architect at Bologna, graduating with honours. He returns to Milan and opens a studio. He is 24. Joining the Futurist Movement, he writes the famous Manifesto of Architecture, and shows his designs at the ‘Famiglia Artistica’. War breaks out. Volunteer in the bicycle corps. Second lieutenant in the bombardiers. Silver medal. On 10 October 1916, commanding a squad of shock troops at Monfalcone, a bullet in the forehead.

SANT’ELIA AND THE NEW ARCHITECTURE

Sant’Elia, the Futurist architect from Como who initiated the global revolution in architecture in 1914 and who died gloriously on the Karst Plateau with a bullet in his forehead on 10 October 1916, now appears to me in three typical and vivid moments of his life.

A former socialist torn by interventionism away from internationalist pacifist humanitarian theories, Sant’Elia strains at the leash along with me, Boccioni, Russolo, Erba, Funi and Sironi in the village of Assenza on Lake Garda, where as volunteer bicycle troops we are reduced to spying on the nocturnal dialogue of traitorous lamps. It’s a muggy afternoon in August. Boccioni, Sant’Elia and I, lying on three enormous rustic beds. Sant’Elia’s hoarse voice speaks of Futurist architecture, berating architectural hybridism. His sharp and aquiline features, flushed but not spoiled by freckles, latch onto and capture the outlines of the constructions evoked by his words. Rainbow bridges, bands of lifts that sink into the dipping storeys of the cities of the future, etc. A soldier enters with an order from Captain Monticelli granting Sant’Elia his first leave.

A surge of envy on our part, followed at once by the artistic joy of seeing Sant’Elia leap to his feet, his long and thin body shaken with enthusiasm like a poplar by a storm, and with its long branches stretched out towards us, crying:

‘What joy! What joy! I yes, you no! She is waiting for me. I have three of them, all beautiful. And you will be staying here. I feel the frenzy in my muscles. I’m a hero, I’m not yet a hero. But they’re all waiting for me anyway. I will have them all, I will kiss them all. For you nothing!’

Without rancour we smile at his crudely boyish spirit, while he rushes out like a whirlwind, gathering up rifle, haversack, canteens, shirts and coat under his arm and away…

I see Sant’Elia again two months later, squeezed with me into the mountain hutment of Redecol (Monte Altissimo). Greenish dawn, stale smell. Our bodies clenched in the struggle against 20 degrees below zero have the limp forms of dead fish at the bottom of the sea. Sleep softens the fierce, hawk-like profile of my snoring friend. An hour later we set off for a demonstration up on the ridges that lead from the Three Alberi to Varagna.

The aim is to alarm the Austrians, so that they will concentrate all their forces against us and neglect their defences on the other side of the lake, to our left in Val di Ledro and to our right in Val d’Adige, which are going to be brutally assaulted by our infantry. I tell my Futurist friends to meet up with me at the front of the platoon so we will be chosen to advance at the spearhead of the battalion.

Boccioni, Sant’Elia and the painter Bucci give me command of the little reconnaissance and we move at a faster pace.

‘First among the first we must be!’ cries Sant’Elia. ‘I will rebuild the trench!’

We approach the trench of the Tre Alberi, from which we see sneak out two, then two more, then three Austrians crawling through the grass.

Our joy is indescribable. Boccioni does not hold back his banter and his mockery of the enemy. Sant’Elia, with his multicoloured camouflage, shapeless and lopsided beret that fits in with his hooked nose and hollow reddish cheeks and the enormous serpent of his rolled-up blanket slung across his shoulders, epitomises all soldiers of fortune and all Garibaldian and Mexican volunteers, all the magical daredevils of an ideal patriotism.

‘You can no longer deny, dear Futurists,’ says Bucci, ‘that I am a painter in the vanguard…’

Fifty metres from the enemy trench we throw ourselves to the ground. Sant’Elia nearly runs himself through with his bayonet as he falls into it. Lieutenant Zanetti catches us up and invites Boccioni and Sant’Elia to go farther forward with him. And we see the two of them crawl on all fours, bayonet between the teeth, as far as the bend in the path, and then go down, all the way to the barbed-wire of the Austrian trenches. After that we fought faraway from one another. In July 1916 a letter from him informed me of the grounds for his silver medal:

‘Under a heavy and deadly fusillade from the enemy he ran bravely to take command of the bombardier platoon; wounded in the head, he returned to the line as soon as his wound had been dressed in order to encourage and incite the soldiers by his example and his words to persist in the defence of the new position gained on Monte Zebio—6 July 1916.’

Shortly afterwards the Brigate Arezzo to which he belonged got ready to overcome the last resistance of the Austrians on the Monfalcone front. The brigade commander, General Fochetti, assigned Sant’Elia and Mario Bazzi the task of designing the cemetery that would serve to house the glorious dead of the brigade.

In this he displayed a fussiness with regard to the alignment of the graves that seemed of ill omen to Sant’Elia. In jest, of course, he proposed that the tomb of the valorous general be constructed in the place of honour. By a tragic twist of fate this place of honour was occupied by Sant’Elia.

In fact, on 10 October 1916, the brilliant Futurist architect took charge of a force of commandos, formed of volunteers willing to fight to the death and armed with bombs, wire-cutters and daggers.

Some were dressed in armour with Farina helmet and breastplate: Sant’Elia with the blaze of his red hair in the wind and his friendly cigarette between his lips, its spiral of smoke perhaps tracing the curves of the beautiful Milanese girls that he loved as well as the soaring lines of the Futurist bridges he had built.

Emerging from the opening at level 85, he shouted:

‘Lads, tonight we sleep in Trieste or in heaven with the Heroes!’

From levels 95, 57, 77 the Austrian machine guns struck that potent life launched towards glory with three shots in the forehead. All the guns, meanwhile, converged their fire on the hill that now bears the name of Sant’Elia and on the nearby one that bears the glorious name of Toti.

On 16 October a letter from Sant’Elia’s comrade-in-arms Second Lieutenant Antonio Giovesi reached me at the front with the news of his death: ‘[…] I must fulfil my mission because the last request of the good Sant’Elia, expressed to me the day before his splendid end, is for me a duty. ‘If I die, ‘he said to me, ‘‘dear Giovesi, you will remember me to the poet Marinetti’’—and the usual gesture of tidying his long hair… When I kissed his corpse, I felt all the pride of having kissed a hero.’

Adolfo Cotronei, who was also a fellow soldier in the same regiment, wrote to me at that time:

‘If you commemorate poor Sant’Elia, it will be no exaggeration to say that he always fought like a hero.’

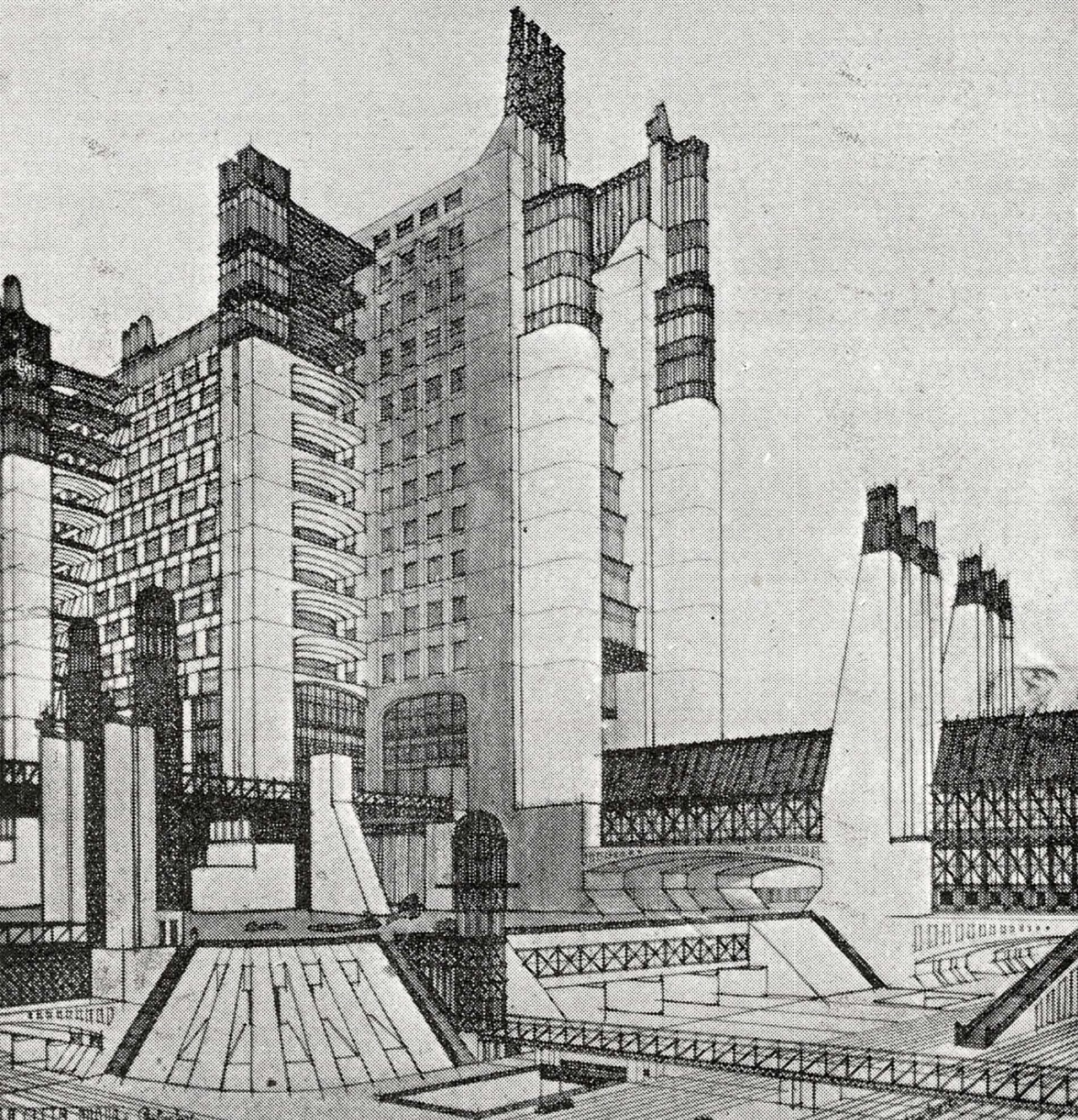

The manifesto of Futurist architecture launched in Milan by Antonio Sant’Elia on 11 July 1914, on the occasion of his Exhibition of the Future City at the ‘Famiglia Artistica’, contained these declarations:

‘[…] creating the Futurist house from scratch, drawing on every resource of science and technology, magnanimously satisfying every demand of our habits and minds, rejecting all that is grotesque, heavy and antithetical to us (tradition, style, aesthetics, proportion), establishing new forms, new lines, new harmonies for profiles and volumes, an architecture that finds its raison d’être solely in the special conditions of modern living and its corresponding aesthetic values in our sensibility. Such an architecture cannot be subject to any law of historical continuity. […] Futurist architecture is the architecture of cold calculation, bold audacity and simplicity; the architecture of reinforced concrete, iron, glass, textile fibres and all those substitutes for wood, stone and brick that make it possible to attain the maximum of flexibility and lightness.

Decoration, as something laid on top of architecture, is absurd, and the decorative value of Futurist architecture can only derive from the use and original handling of raw, bare or violently coloured materials. Just as the ancients drew their inspiration in art from the elements of the natural world, we – as materially and spiritually artificial beings – must find that inspiration in the elements of the brand new mechanical world we have created, of which architecture should be the finest expression, the synthesis […]. By architecture must be understood the effort to harmonise with freedom and great daring the environment with man, that is to make the world of things a direct projection of the world of the mind […].

This rationalism of Sant’Elia’s achieved:

1st a destruction of decoration based on superimposed styles;

2nd a perfect correspondence between exterior and interior, purpose and form, hygienic convenience and form, landscape-climate and form-proportions;

3rd an asymmetry balanced by a harmony of plans and masses;

4th a full utilisation of new building materials and the new possibilities they bring.

This manifesto and the models that illustrated it were reproduced in the main journals of France, Germany, Britain and America, and publicised all over the world by hundreds of conferences.

Out of it came the great architectural revolution that after the war brought to the fore the names of the foreign Futurists Mallet-Stevens, Le Corbusier, Doesburg and many others. This global movement springing from Sant’Elia was at first, especially in the countries of Northern Europe, exclusively rationalist, devoid that is of the great colourful and dynamic lyricism that characterised the architecture of its Italian initiator. It displayed simplicity, practicality, calculation, geometricism, standardisation in black and white and thus a deplorable funereal monotony.

The Futurist approach developed two years ago by Mallet-Stevens at Auteuil avoids this defect. Its colours and the variety of its forms would have thrilled Sant’Elia.

Sauvage’s project—a skyscraper that houses 10,000 tenants and 4000 cars on 20 floors—represents the type of stepped building with bands of external lifts conceived by Sant’Elia.

* * *

In Italy, after the death of Sant’Elia, the architect Virgilio Marchi took the lead in the combative campaign with his book L’architettura futurista.

The question, in his view, ‘begins from a dual problem of identity. The identity, for all races, of certain necessities of life created with progress and the identity, for all countries, of the latest construction material. Therefore: “Speed and universal sense of speed create a global type of building…”’

The work and lectures of Virgilio Marchi were followed by the highly original advertising stand created by Depero at Monza. Finally the dynamic and polychrome Futurist pavilion designed by the painter, sculptor and architect Enrico Prampolini and organised by Fillia appeared at the recent Exposition in Turin, whose buildings were almost all freed from the hybrid mixture of classicising styles, and marked by the genius of Sant’Elia.

Futurist architecture, says Enrico Prampolini, can be summed up by two expressive terms: lyricism and dynamism. The lyrical vision of the architectural idea finds its stylistic equivalent in plastic dynamism. […] Futurist architecture is the style of movement made concrete in space […]. The reign of the machine has opened up new stylistic horizons for us, for new mechanical landscapes have been revealed to our eyes.

The problem of the new architectural aesthetic and of the practical and lyrical utilisation of the new materials is closely bound up with the problem of the economy and speed of construction and implicitly with standardisation.

On this subject the Futurist architect Alberto Sartoris has written:

‘There is nothing to be feared, because standardisation neither should nor can limit architectural invention, and there is no need to worry about uniformity, since elements in repeated, superimposed, alternating series are susceptible to infinite applications and can give rise to the most diverse plastic plays of volumes or masses. Judiciously arranged and severely composed, large modern buildings cannot produce the dreary symmetry of some of the last century’s squares.’

But the rationalist conception did not shackle Sant’Elia and still less does it shackle the Futurist architects of today.

A man, emerging from his rationally constructed home, should not find in the city (his second home) a symmetrical monotony in funereal and depressing black and white.

So what is needed in architecture, in addition to the foregoing values, are:

1st a dynamic synthesis of form;

2nd a dynamism of colour regarded not as a decorative element, but as an architectural force;

3rd an eccentric audacity of canopies, galleries, balconies, bands of external lifts, terraces and towers, obtained through the use of the new construction materials;

4th a surprising range of clever ideas and technical problems solved with the originality of the never seen before that is disconcerting at first, and then undoubtedly attractive;

5th an uplifting, aviational, cheering, exciting, optimistic lyricism, that is indispensable in all of humanity’s new constructions.

All this in the light of the genius of Sant’Elia, whose primacy in the revolution in world architecture has been recognised even by the French, despite a jealous defence of their own innovative force.

In fact Antoine has written on the subject of architecture and decorative art in the Journal: ‘On the other side of the Alps the way had long been cleared by the school of Marinetti.’

In his Littérature italienne, Benjamin Cremieux has written: ‘It is outside Italy that Futurism has had the most influence. F.T. Marinetti is right in claiming that Orphism, Creationism, French Surrealism, Russian Rayonism, British Vorticism, German Expressionism, Constructivism, Spanish Ultraism and Anglo-Saxon Zenithism, in short, all the avant-garde schools in the literary or artistic domain have owed something to Futurism since 1909.’

F. T. ΜARINETTI.

Translated by Christopher Huw Evans.