Medieval Masons and Tracing-floors

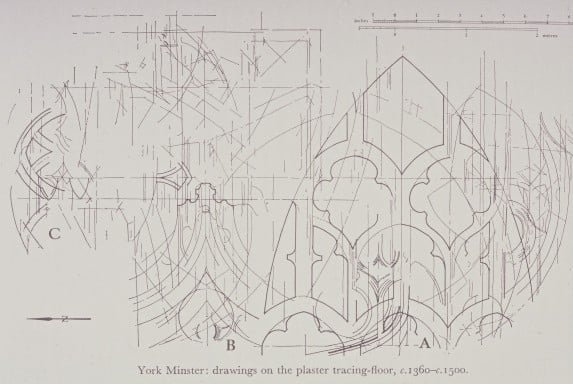

The tracing-floors of York Minster offer a rare glimpse into the relationship between drawing and the Cathedral, the most iconic monument to medieval Gothic. Tucked away into the loft of a small vestibule connecting the North Transept to the Chapter House, the Mason’s Lodge, as it is known, is one of only two surviving tracing floors in England; the other resides in Wells Cathedral, Somerset. Laid with several thin layers of plaster of Paris, the floor was a convenient space for the master mason to draw designs for elements and moldings to scale. There is evidence to suggest that a new layer of plaster would be laid at regular intervals and trampled flat to provide a fresh working surface, with the plans copied onto thin timber or metal sheets for templates. Drawings could easily be brushed out or partially erased, with the most recent etchings shown in the sharpest, clearest white.

This temporary medium for drawing indicates that the process of iterative design was practiced by medieval masons. With an already limited number of drawings by masons, it is perhaps more incredible that we retain examples of such a transient practice. The surviving tracings-floors at York Minster, believed to be for the construction of the parish church of St Michael-le-Belfrey, are significant for the insight they provide into the role drawing played for the medieval architect.

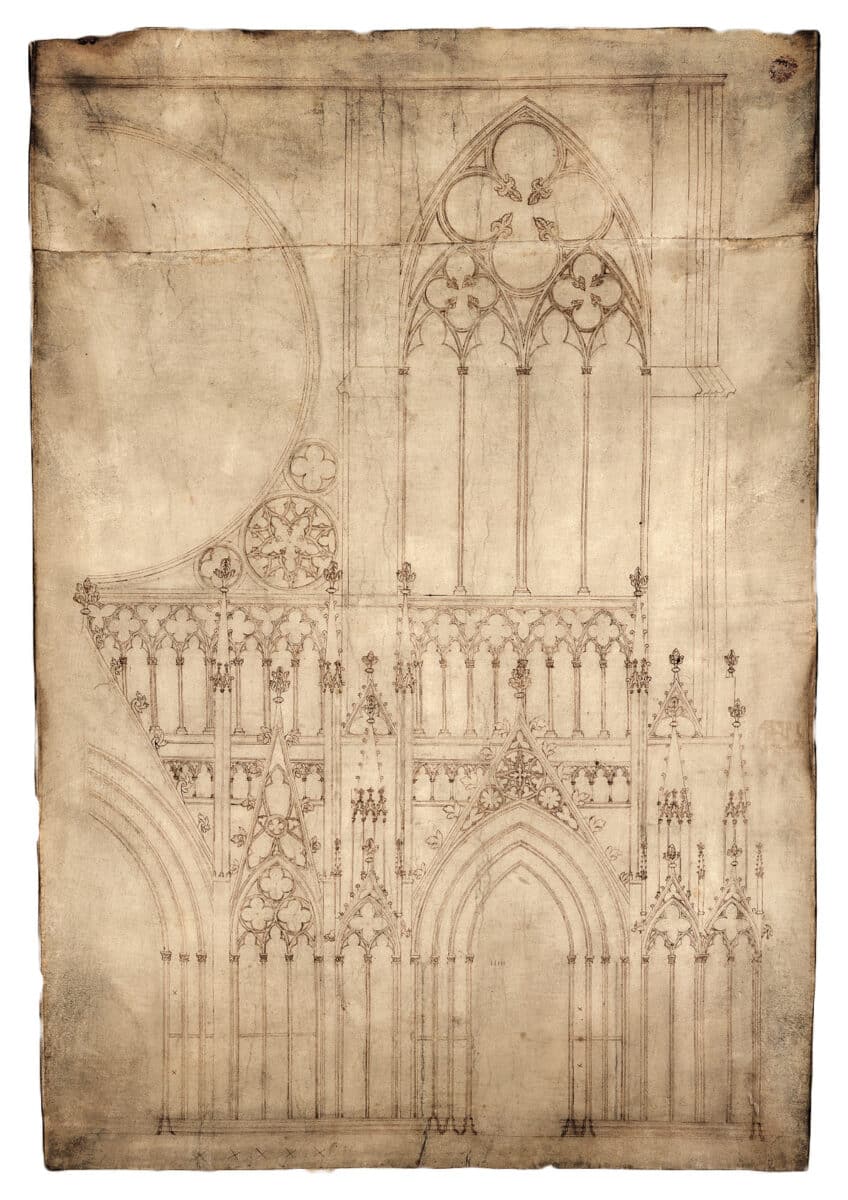

The role of design in the Gothic cathedral has long divided opinion. We have a tendency to see the cathedral, a source of awe and veneration separated from contemporary architecture in scale and ornament, as a monument built to embody a transcendental or Promethean vision. The cathedral as an opus in mente conceptum derives from a romantic understanding. This is supported by the lack of any complete architectural drawings as we would understand them. The drawings that do survive, as in York Minster, or the more or less complete parchment drawings of Strasbourg Cathedral, seem to be templates for specific elements rather than evidence of a holistic design. The deeply experiential and complex structural form of the Cathedral makes it difficult to assume they could ever be understood in totality, or fully rationalised through drawing.

The coordination required to construct a Gothic cathedral was ambitious and required a large number of skilled trades and labourers. The Master Mason, or Stonemason, was responsible for all aspects of the cathedral’s construction. While the dogma and influence of the Church could inspire such large-scale projects, the logistics and material investment would be impossible to justify if there were not a plan to work to or an ultimate vision to present. Some point to contemporary practices of washing parchments for their reuse, and the potential loss of drawings on organic materials such as timber or parchment over time, to demonstrate that a lack of surviving evidence cannot rule out the role of drawing as being one we would be familiar with now. The tracing-floors layered and intersecting markings (as seen in John Harvey’s drawing) suggest that despite representing individual elements, each drawing was created in relation to another. Designing individual elements would have been necessary when drawing at this scale and may have been a way to make the drawing and design of such a large monument more manageable. These interpretations, however, perhaps attempt to locate the Gothic cathedral within a contemporary understanding of the relationship between architecture and drawing.

The placement of the tracing-floors within the Mason’s Lodge at York Minster reveals a different dynamic. It is clear that the drawings were not only an iterative method to create templates, but a process of design. The room is too inaccessible to have been used to trace the designs directly onto the stone, as had previously been assumed, and its presence within the Minster itself, rather than amongst the workshops outside, speak to its importance and the need for design to be carried out in close proximity to construction. There is also evidence that there was a close relationship between the tools used for drawing and the tools used to mark materials or the ground for cutting. For the masons responsible for York Minster, drawing was tied to their skill in construction. It would have been easy to transfer a scaled floor plan constructed and measured using pins and string to the worker marking out the site with stakes and rope, without the need for modern aides. The structure was designed through the application of geometric principles, rather than mathematics, allowing these simple tools to result in the complexity witnessed on the plaster floors and in the finished Minster.

The tracing-floors represent a period of architectural drawing where the building was conceived as a sculptural and solid mass, rather than the result of a network of lines flattened into two dimensions. The drawings in plaster are not just tracings or depictions of intent, but a thoughtful and methodical process that would involve bodily navigation, collaboration, and a skilled connection with materials. It was not an act that could be rushed, but one which promoted dwelling and careful consideration. This process blurred the line between drawing and construction, with the Cathedral itself became an act of drawing.

The elevations of Strasbourg Cathedral, whilst bearing pinprick marks that point to the use of similar geometric techniques as at York, show the beginning of the formalisation of drawing away from this constructive practice. In contrast, the plaster floors of York Minster imply a practice where drawing and construction formed key and interlinked parts of the design process. This is a method of working that practices are slowly rediscovering. The adoption of VR, BIM practices, and emerging construction techniques like concrete printing, will begin to turn the process of drawing and design back into a more three-dimensional and sculptural understanding of space. Though made at a time when the role of the architect and drawing were neither formalised nor distinct, the tracing floors in York show how the two seemingly disparate fields of drawing and construction can become part of a simultaneous design process.

Jennifer Smith is currently studying for an MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design at the University of Cambridge.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.