Ove Arup: Engineering the World

My introduction to the work of Ove Arup, the great Anglo-Danish structural engineer whose firm made both the Sydney Opera House and the Pompidou Centre in Paris buildable, came over the course of three years as I walked, almost every day, across his Kingsgate foot-bridge in Durham. This is the pedestrian conduit from the ancient heart of the city with its castle and cathedral across the gorge of the River Wear to the new faculty buildings and later colleges on the other side of the river.

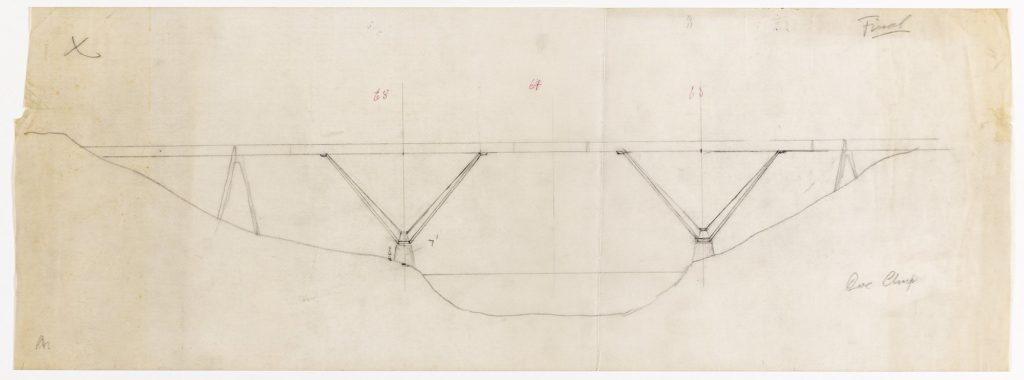

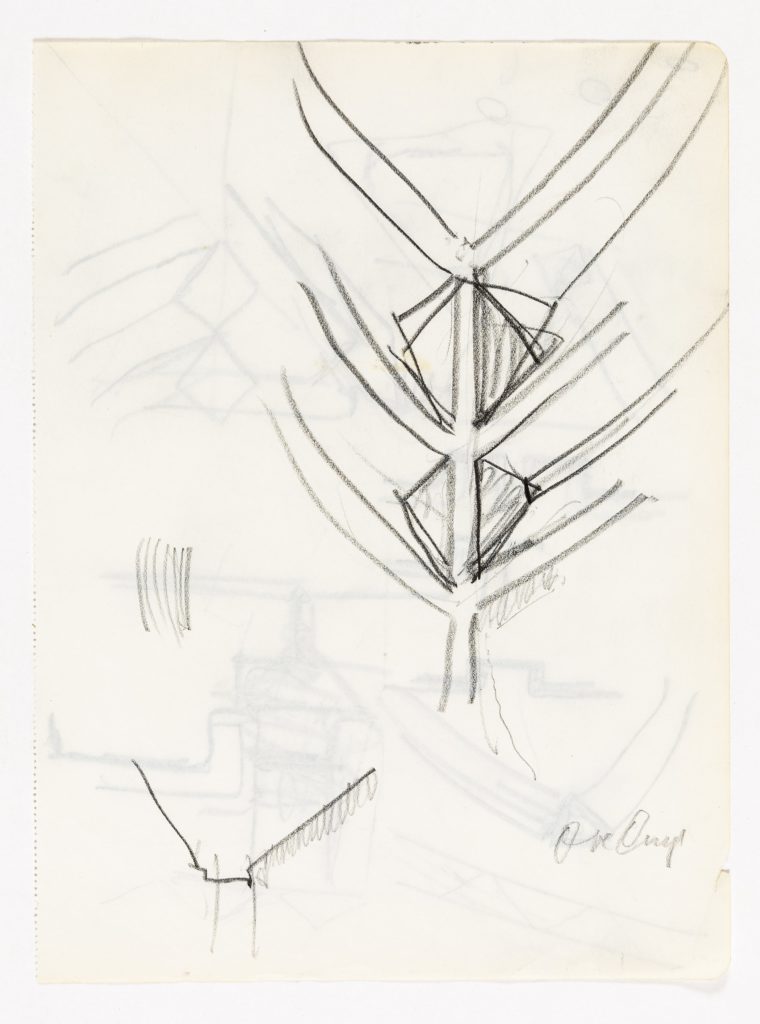

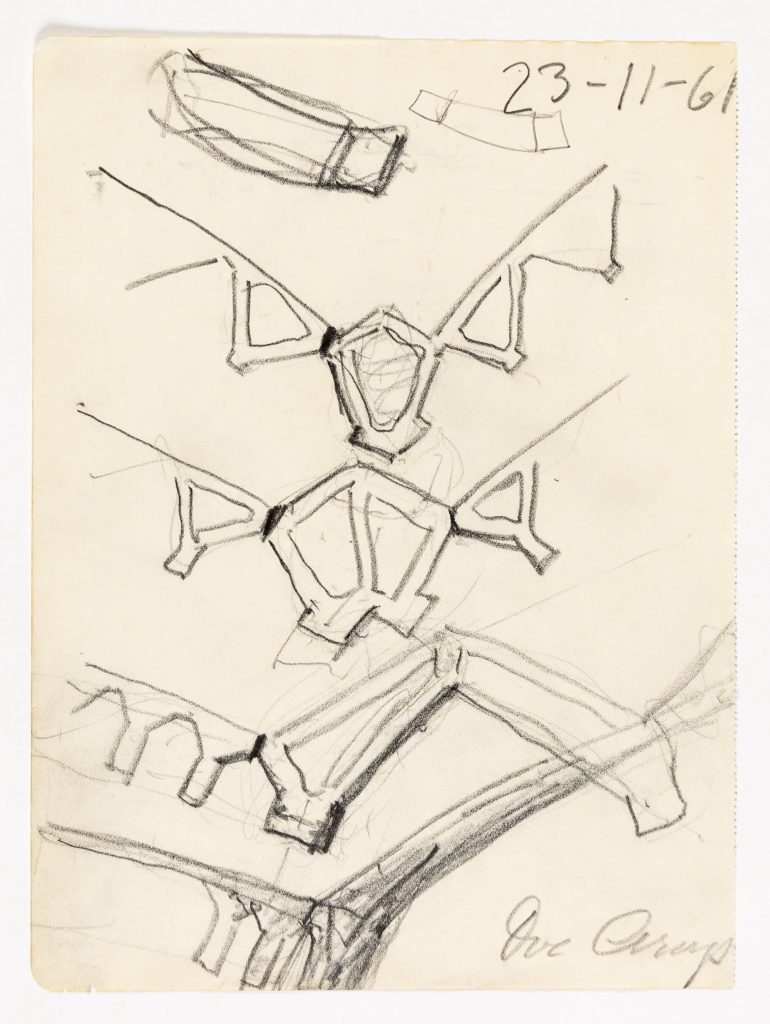

I would go on to learn that this was the last structure that Sir Ove had personally designed and overseen, in every detail, in the early 1960s. At the time I grew familiar with it, I liked it because it some-how resembled an aqueduct, being a sophisticated concrete trough. However, this was a trough that broke in the middle where the two halves of the bridge joined. Or rather, touched, with beautiful bronze expansion joints on either side expressed as tabs between rollers.

I was told that the bridge had been made in two perfectly balanced tree-like halves, erected parallel to the banks of the river, and then rotated across to meet in the middle. This seemed improbable, and there were many other fanciful stories, mostly to do with the way it moved in the wind and could fall down at any moment. The latter was nonsense, as time has proved – it has stood happily for nearly 60 years now. Somehow a bunch of students managed to suspend an old car beneath it one 1960s rag week, so it is pretty strong. But the rotational construction story is true, as is the fact that the bridge is slightly lively.

As you walked across it the concrete paving planks would clunk softly, and at times it seemed that it was ever so slightly out of true in the middle – whether the result of wind, heat expansion or optical illusion, I don’t know. Somehow it seemed to correct itself. I was pleased with the way lighting was concealed beneath the broad balustrades, and that those balustrades sloped slightly inwards, with their own integrated drainage. The rows of stubby concrete drain spouts on either side were medievally satisfying. I liked the fact that there was a kinked approach to it at both ends, which nicely delayed the point at which you emerged on to this high-level catwalk. The mystery was enhanced on the west side by the fact that you descended steps with finely crafted iron handrails from the bottom end of cobbled Bow Lane, then passing through trees to get to the bridge proper. And it also seemed good that the structure seemed to be part of a compositional piece with the angular student’s union complex on the east bank: a building I later discovered was by Architects Co-Partnership, but also engineered by Arup.

The careful detailing continues in the ultra-subtle patterning given to the surface of the moulded concrete. It’s a masterly work, has lasted well, and sits very happily beneath what is now, after all, the World Heritage site of its Norman cathedral and castle complex. But it is remarkable in another way, because while Arup was designing and supervising the making of it, he and his eponymous firm of engineers were working on their most challenging project yet. Exactly how could you build what seemed at the time to be impossible – the Sydney Opera House? This was to become one of the most fascinating engineering/architectural political/cultural tests of its time and was to lead to a falling-out and eventual reconciliation between Arup and his fellow Dane, the architect Jørn Utzon. Arup foresaw the main problem when he personally contacted Utzon for the job in 1957, just after the latter had won the architectural competition for the opera house. Arup told Utzon in a cold-call letter: ‘As far as I can see, it will not be so easy to calculate and detail your design so that your idea is realised in the fullest sense, and for it still to be economically viable.’

He was not wrong. It was to take sixteen years to build the Sydney Opera House and it ended up costing more than fourteen times its original highly optimistic budget. Utzon finally resigned, forced out by local politics, but Arup kept faith, and made possible the most instantly recognisable building in the world. Back at the start, he had commented: ‘The Opera House could become the world’s foremost contemporary masterpiece if Utzon is given his head.’ And today, in a link with that little Durham footbridge of the same period, it is a World Heritage site in itself.

Afterword

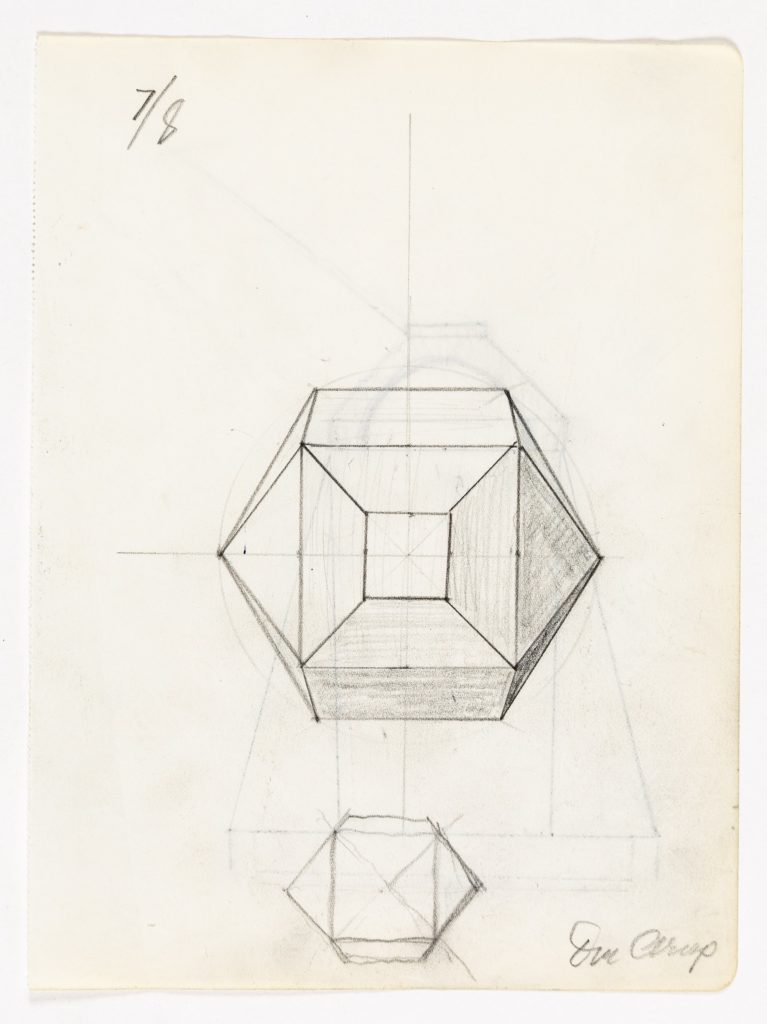

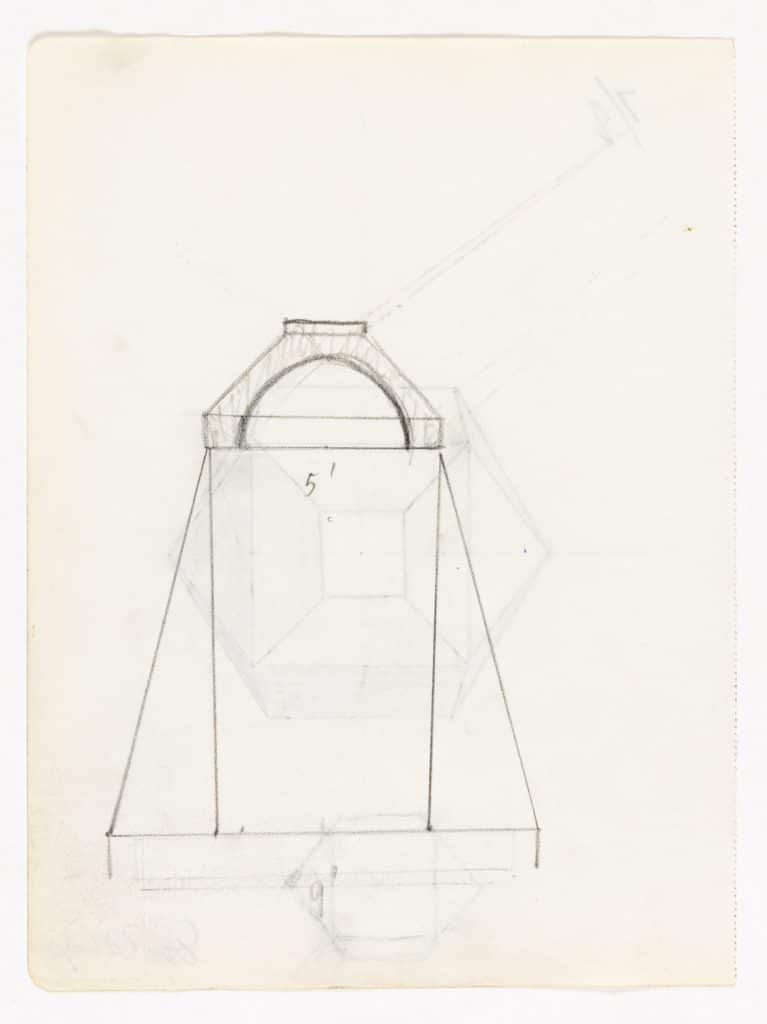

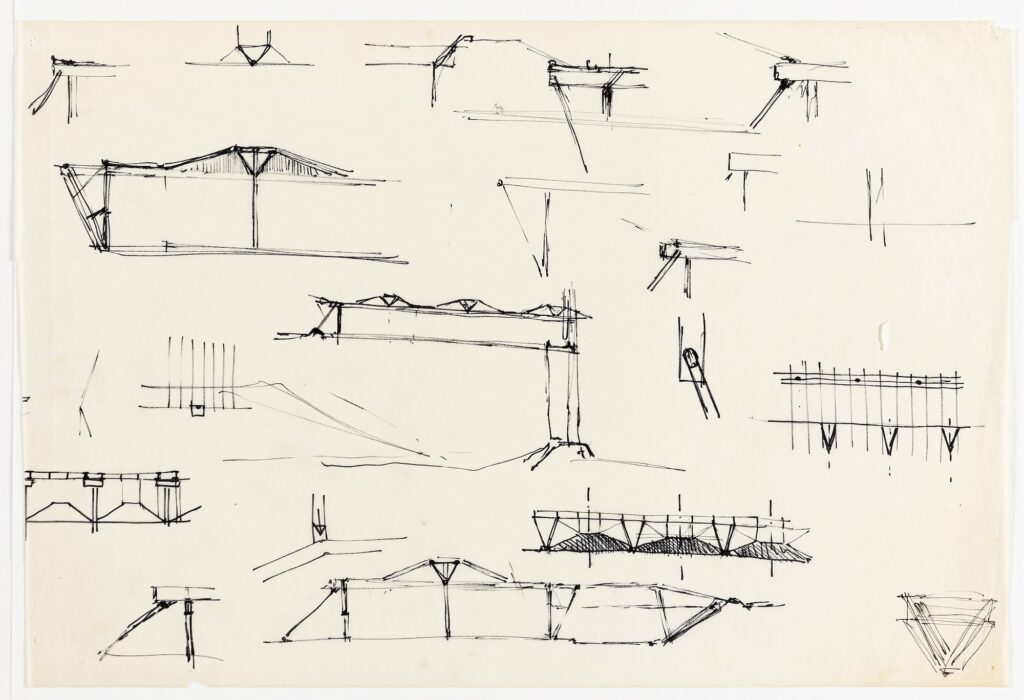

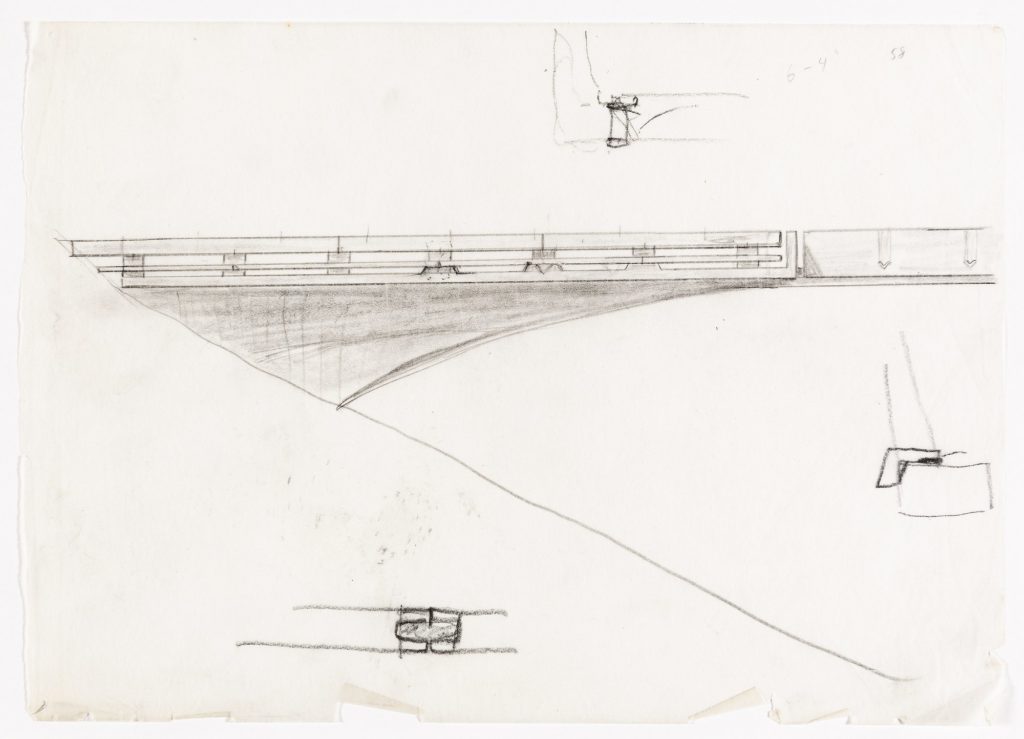

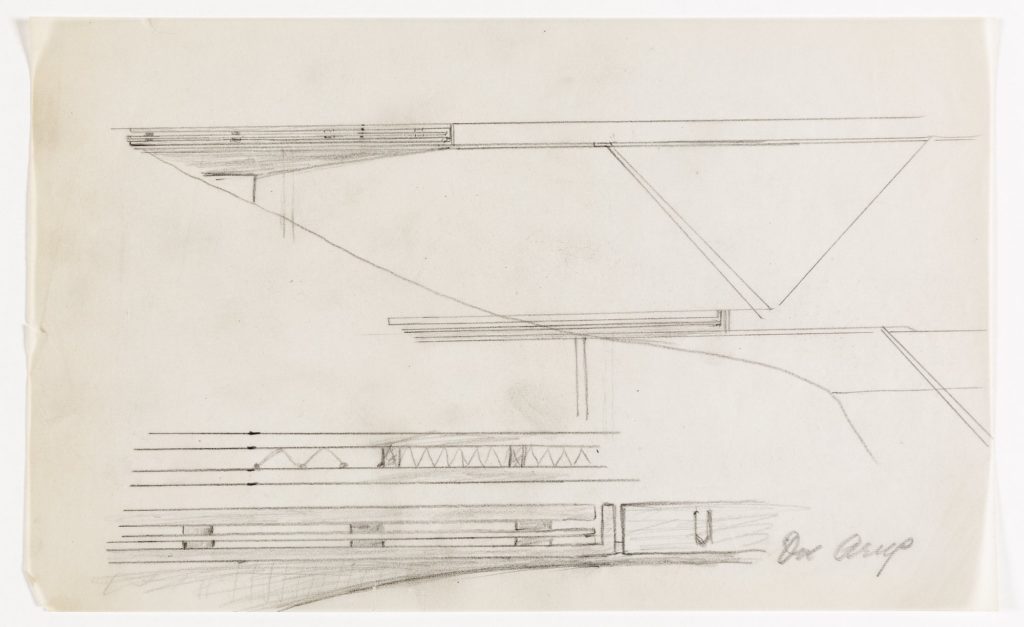

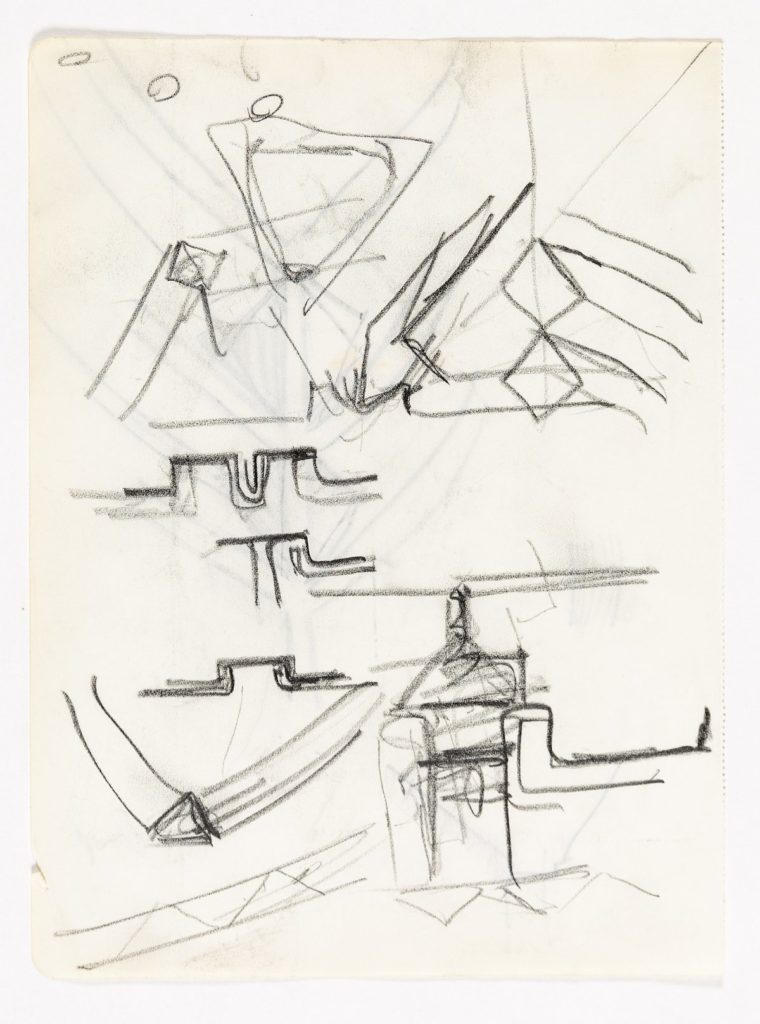

I have returned to walk across this bridge many times since. It is weathering well, still with that air of inevitability, of rightness, about it, and it easily accommodates the greatly expanded student population it anticipated. I was intrigued to see Ove Arup’s sketches in the Drawing Matter collection not least because in fact there was, as usual in these cases, nothing inevitable about the eventual outcome. Arup explores various structural concepts for spanning the gorge, some showier than others, before plumping for the balanced rigid trough arrangement. And the drawings show something it is quite difficult to appreciate on the spot: the long cantilever springing from the cathedral side of the gorge, its balustrades slightly differently detailed because they do not play a structural role, its tip angled to meet the line of the main bridge. This section is shrouded in woodland but it is quite an engineering feat in itself. Nothing is ever perfect but this bridge, in my view, comes pretty close.