Michael Graves: Fargo-Moorehead Cultural Bridge

The Fargo-Moorhead Cultural Bridge is an unrealised project combining infrastructural and cultural programs: a vehicular bridge between two cities over the Red River, a performing arts building in Fargo, North Dakota, the Red River Valley heritage interpretive centre in Moorhead, Minnesota, and at the centre over the river itself, an art museum. It was, architecturally speaking, a poignant statement in how to bridge communities and combine civic and cultural programs. It was also one of Graves’s early statements in postmodernism. The project’s legacy, however, established in its drawings, also rests in the realm of art.

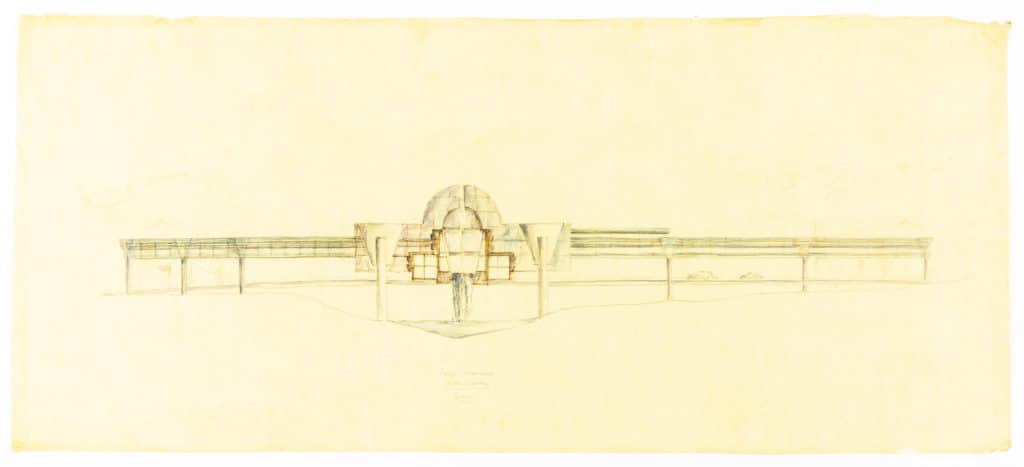

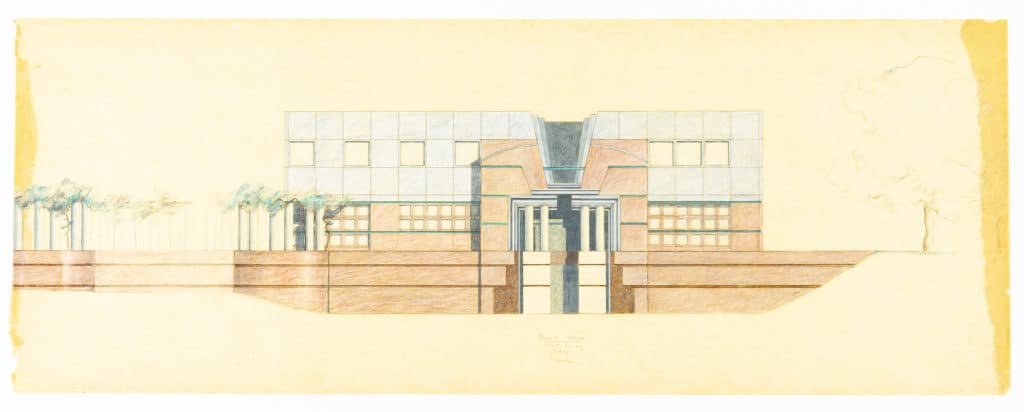

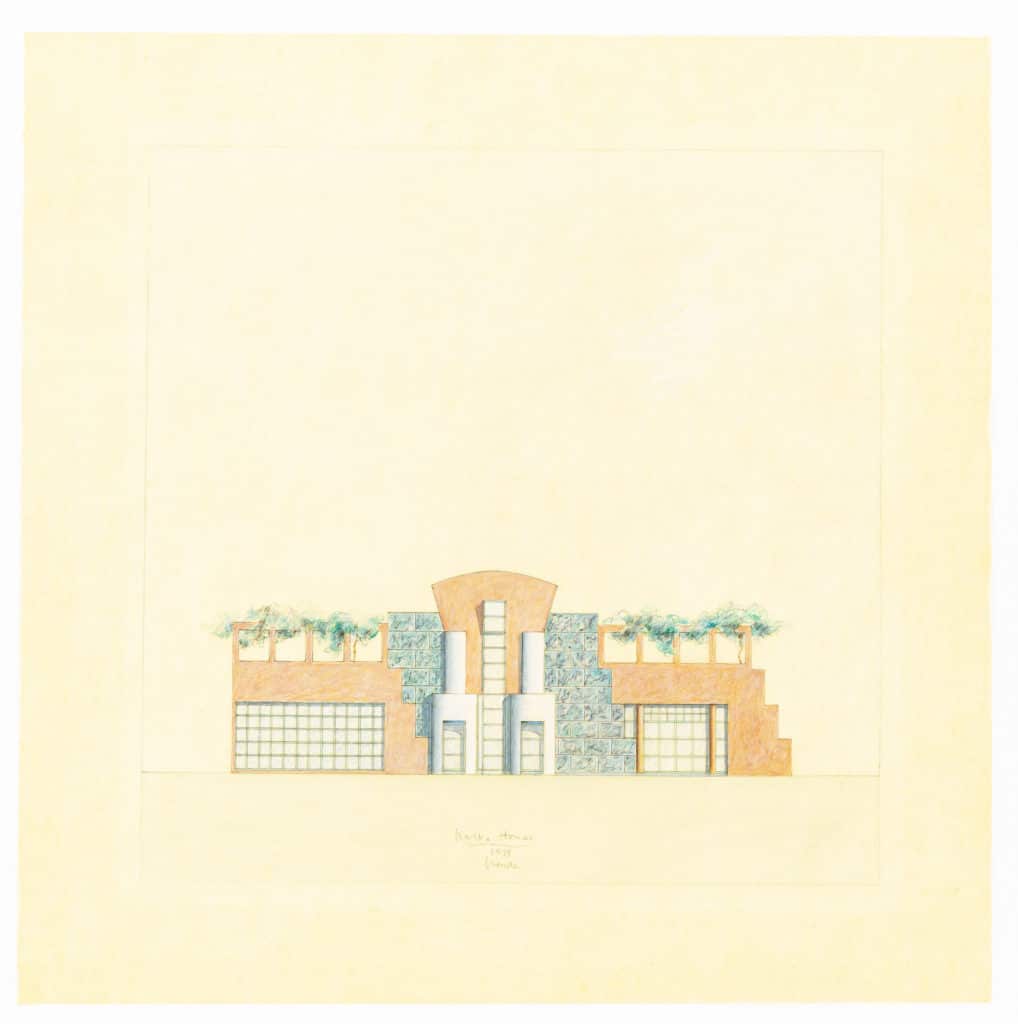

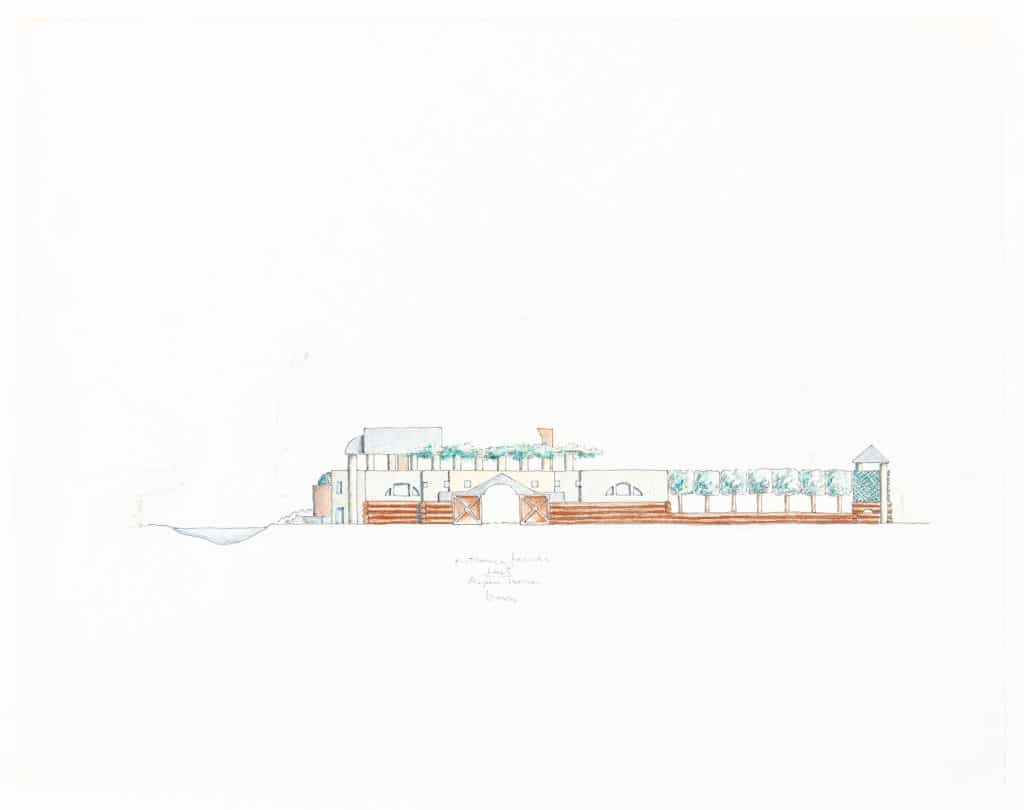

When Graves’s proposal was revealed, the influential architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable called the presentation drawing ‘probably one of the most beautiful architectural drawings of recent times’. The drawing at Drawing Matter is an earlier scheme than the one Huxtable saw; it is not, as Graves would describe it, a ‘definitive drawing’, but rather a ‘preparatory study’. It shows the central art museum pavilion and thin, floating glass facades extending outwards from it. Three columns of different intercolumniation with oversized, applied capital-forms visually support each thin glass element. The performing arts and heritage centres do not yet exist as side pavilions. The landscape underneath the building is also not the same as the final scheme, indicating that either the site had been changed slightly or that at this stage Graves was unsure of the site’s grading. There are trees and cars, both of which are left out of other, more final drawings. One can only see the south façade and not the offset north façade that would develop. Present, however, are many elements that would make it into the final design. The general form of the central pavilion is similar. Graves’s play with keystones – a feature in much of his work – makes one of its earliest appearances here. Another Graves drawing from 1978 in Drawing Matter of the Plocek House also exhibits this motif.

Keystones are absent where they should be and present where they are unexpected. The non-structural barrel arch that caps the central pavilion is missing its keystone, while a keystone form makes an appearance just below as a large set of picture windows. Out of its base, in homage perhaps to the director’s house at Chaux, flows water into the Red River. Keystones also become monumental column capitals to the left and right, which though also serving no structural purpose, give the visual impression of holding up the central pavilion so it floats above the road and the river. It is a project that revels in postmodernist capacities to subvert received historical elements into aesthetic motifs.

The drawing is a façade, a representational technique that Graves argued, in reaction to the modernist reliance on the plan, was important to the experience and understanding of architecture. There is shadow and a certain amount of depth. Materiality can be made out, though if not specific materials at least indications of them. The drawing is on yellow trace paper – an extremely fugitive material also called trash – and drawn with graphite and blue and muddy red coloured pencils. Underneath the drawing Graves has titled it, signed it and dated it.

Graves began this practice of titling, signing and dating only once he understood that his drawings, even when on yellow trace paper and without museum quality materials, had aesthetic value. This was the same moment that he understood that his drawings would sell. Graves did not always consider his drawings in this way and would not sell them, when asked if he would, early in his career.

As both architectural and aesthetic works, his drawings have been collected by numerous individuals and institutions. A gouache and pen and ink drawing on trace paper of Fargo-Moorhead from 1978 was sold, framed, in 1997 at Christie’s. A 1978 detail of the middle section of the bridge from the final scheme, of more finished quality than the Drawing Matter version, though still on yellow trace, is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. A complete south façade drawing of the final design in colored pencil and graphite on white wove paper, dated 1979, is at the Cooper Hewitt, having made its way to that collection in 1980.

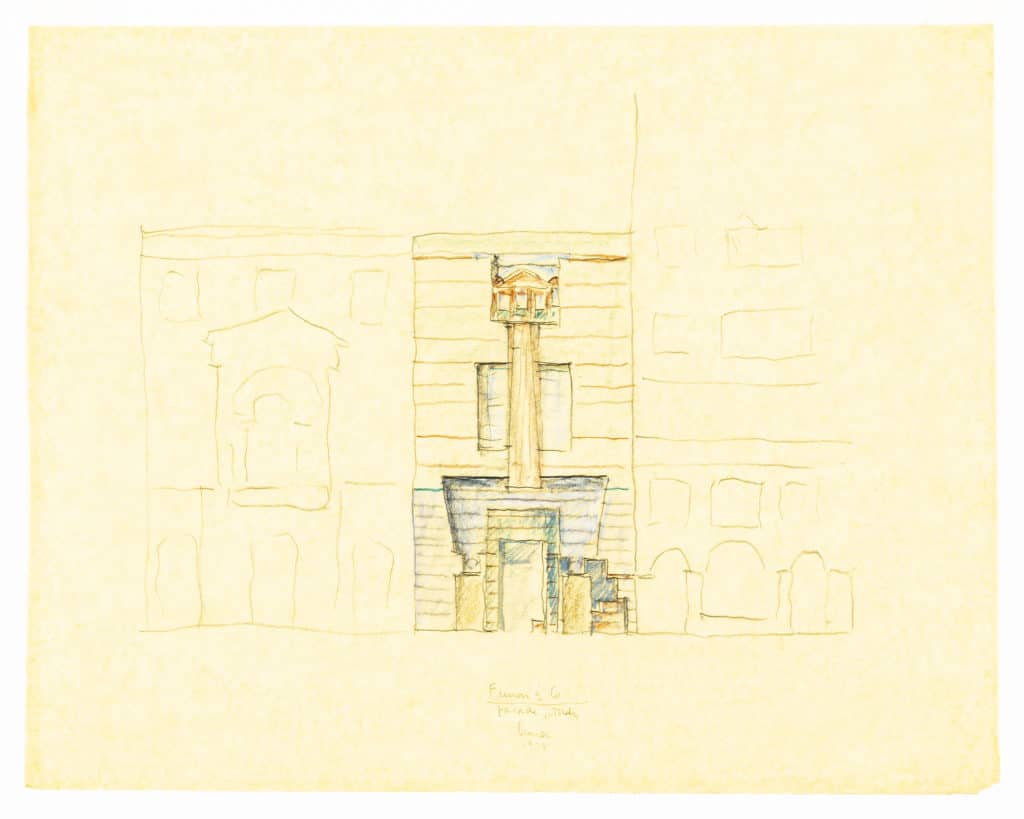

This particular drawing, as well as others in the Drawing Matter Collection – of the Plocek House, the Kalko House, French & Co., the Aspen House – were exhibited in 1979 at the Max Protetch Gallery, a well-known private gallery that emphasised architectural drawings as art. It was Protetch’s first exhibition of solely architectural material and his first exhibition in his famous gallery space on West 57th Street in New York. Huxtable attended this show, which, she asserted, represented a breakthrough by engaging simultaneously with architecture and art. She emphasised Graves’s use of colour, and concluded that ‘the drawings are such elegant artifacts in themselves’, and they ‘represent what surely must rank among the most delicately assured and beautiful drawings to be seen in or out of the field of architectural design’. Huxtable also underscored the difference between drawings and buildings: ‘But something happens in the translation of the picture plane to the real world, and there are executed works that simply do not read the same way as they do on paper; the refined intelligence can turn into something fussy and obscure.’ The drawings, she implies, reveal a purer vision of the architecture than is represented in a building. Drawings, here, take precedence over built work, and exist both in the realm of architectural design and as artworks in their own right. While this is a perception that would fully develop in the years to come, it is with drawings like this one where it began.

This article celebrates the publication of Jordan Kauffman’s book Drawing on Architecture: The Object of Lines, 1970-1990 (MIT Press), which will be available at the Drawing Matter book launch, Architectural Association, 17 October 2018 and from MIT Press.