Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy

Livia Lupi’s book Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy: Innovation and Persuasion at the Intersection of Artistic and Architectural Practice addresses a topic of recurring interest to readers of DM and DMJournal: the relation of actual to pictorial representations of architecture and its ornament in early fifteenth-century Italy. Harvey Miller has adorned the text with superb colour illustrations that alone solicit praise.

In her introduction, Lupi poses ‘three burning questions: why are so many architectural settings in this medium [painting] so prominent? How do they interact with the narrative, if at all? How did artists understand architectural forms, and why did they labour over them?’[1] These are good questions, which many students of the period will have asked. By way of addressing her answers, parsing her title is a useful beginning.

‘Painting Architecture’ refers to the prominence of architecture in paintings and frescoes of the period. In this, Lupi treats the inherited interest in ‘pictorial space’ with some disdain, on the grounds that false disciplinary boundaries are erected between art history and architecture (and between 2D and 3D concerns) when such distinctions did not exist in Renaissance culture—at least until the advent of the paragone debate. Accordingly, Lupi ‘aims to reorient the discussion away from perspective and pictorial space in order to emphasise artists’ engagement with the architectural forms per se, rather than as a means to achieve a more or less convincing three-dimensionality.’[2] With an impressive command of detail, she faithfully adheres to this procedure throughout, discovering details of column orders, ornament, vaulting, building types and configurations like niches, indicating their analogues in other images, in liturgical furnishings and constructed architecture.

‘Early Renaissance Italy’ is a vast topic of course, accompanied by an equally vast corpus of writing that stretches from the ancient world, through its own self-analysis, to contemporary scholarship. The ‘rebirth’ of the arts, sciences and philosophy, took place amidst wars between city-states, the contest between republican and oligarchic rule, the rise of capitalist economies and the reframing of received theology in Humanist terms. Whether or not one agrees with Harry Lime that violence was necessary for cultural flourishing, Lupi conjures a comparatively peaceful world of refined judgements by oligarchs (from whom most of the beauties of the period indeed derived). She develops her argument through three case studies, all of which refer to Florentine practice: the Baptistery at Castiglione Olona, the Sala di Pellegrinaio in the Ospedale of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, and the Chapel of Nicholas V, in the Vatican.

Lupi pairs ‘Innovation’ and ‘Persuasion’ in her title because she sees the former contributing significantly to the latter. Innovation is a prominent concern throughout the book, and particular credit is accorded to a detail in a fresco which anticipates later architectural practice, and to the artist, whose original use of architectural or ornamental detail is judged to be ‘experimental’ or ‘cutting edge’, granting the patron a high reputation for architectural ‘erudition’ and ‘magnificence’. She rightly notes the frequent depiction in this period of Italian Gothic motifs alongside the early experiments with Classical Orders. The measure of innovation or originality for Lupi is Florentine practice; but one wonders why Padova was not given more prominence, particularly since she has written on one of the remarkable fresco cycles there.[3]

Of the potentially complex relation of Rhetoric to architecture, ‘Persuasion’ is most important for Lupi’s purpose to demonstrate that the works enhance the prestige of the patrons and their institutions, promote a dignified magnificence, or establish legitimacy. Lupi rightly identifies such messages, although Rhetoric’s concern for how a communication is structured (itself always a tension between idealisation and actuality) depends substantially on the modes of involvement of the viewer, and therefore aspects of the ‘pictorial space’ which Lupi seeks to avoid. Moreover, what is communicated in Lupi’s case studies is not limited to these messages, and her twice-cited inspiration, Amanda Lillie’s online catalogue for the 2014 National Gallery exhibition Building the Picture, is more open than is Lupi to the spiritual dramas in the works she considers.[4]

Lupi argues strongly for ‘the Intersection of Artistic and Architectural Practice’ in North Italy of the period. Intermodal studies have usefully challenged disciplinary boundaries, exposing the often-complex web of communication between artists, craftsmen, patrons, supply chains, and so forth, requiring a sophisticated visual culture. Artists could work in several media—Vecchietta, for example, contributed both frescoes and bronzes to the Ospedale and to the Duomo in Siena—and, as Lupi observes in her ‘Epilogue’, the exchange of drawings and prints added significantly to what could be seen in situ.

The three case studies are presented historically, bracketing a fifteen-year period between 1435 and 1450. The first of these is the Baptistery commissioned by the redoubtable Cardinal Branda Castiglioni, as part of his Collegiata atop the highest hill of his native town of Castiglione Olona (about six kilometres south of Varese, now surrounded by a substantial suburbia). Visitors to Rome will know Castiglioni and his artist, Masolino da Pinacale, from the chapel dedicated to Santa Caterina in the church of San Clemente, completed four years before the Baptistery. By comparison to the serenity and equipoise of the Santa Caterina Chapel, or to the complex symmetries of Masolino’s presbytery vault of the Collegiata Church, the Baptistery is quite a different world (Figs 1,2). Much as I am grateful for Lupi’s assiduous tracing of anticipations and echoes of architectural motifs, and at the risk of straying into the forbidden territory of ‘pictorial space’, I would suggest that the most ‘experimental’ aspect of the Baptistery frescoes is the relation of their architecture to that of the Baptistery (unlike the monumental baptisteries of northern Italy, it is a modest single-storey vaulted square with a vaulted apse opposite the door).

As against the conventional compartments of independent views carefully coordinated with the existing architecture, such as one sees in Giusto de’ Menabuoi’s Baptistery at Padova from the previous century (Fig.3), Masolino disposes his frescoes asymmetrically, across corners and transitions from wall to vault. Christ’s Baptism is aligned centrally with a window (whose height establishes the two principal horizons), the altar and the font—but Christ is standing in water whose colour is carried into Herod’s palace, which stretches along the whole north side of the Baptistery until it becomes the deep red colonnade echoing the fresco diagonally opposite. St. John is imprisoned in the intrados of a lateral window in the apse, and he is beheaded opposite a shell niche jammed into the interval between the apse vault and the side wall, and awkwardly furnished with a hexagonal altar (in general Lupi’s artists can do no wrong, but I am not persuaded by her comparison of this niche to Bramante’s Tempietto).[5] The wild landscape which supports St. John’s preaching and the Baptism sweeps diagonally across the apse, and then reappears as an equally sauvage but verdant hillside (occupied by a possible reference to the Collegiata) behind Herod’s palace. Based on Francesco Pizolpasso’s ekphrasis of Branda’s buildings at Castiglione Olona, usefully translated in an Appendix with Iván Parga Ornelas, Lupi adduces the genre of favourable landscapes and sites, popular in the literature of the period.[6] However, I also sense something more violent here, possibly related to the death and rebirth of baptism, in which St. John echoes the sacrifice of Christ (potential comparisons of Herod and Branda would seem out of place, given the latter’s record of good deeds, though the general question of proper noble behaviour was certainly current).

Lupi’s second case study is the remarkable Pellegrinaio in the Ospedale of Santa Maria della Scala, opposite the Duomo in Siena (whose steps gave the name to the hospital). One of the oldest hospitals in Europe (founded legendarily in 898, officially in 1090) devoted to the care of foundlings, the indigent and pilgrims, it closed as recently as the mid-1970s, opened as a museum in the mid-1990s and is still under restoration. Friends of Drawing Matter will recognise this institution as the site for Peter Smithson’s last project (1983), the steel tower whose reinterpretation as a helical wooden obelisk was installed at Hadspen and then at Shatwell Farm. The Pellegrinaio is a forty-metre-long ceremonial hall in the middle of the Ospedale, aligned with the Duomo and divided into five cross-vaulted bays.[7] The ten frescoes required four campaigns and three artists to complete (Lupi concentrates on the frescoes of the third campaign, between 1441-44); and they are concerned with showing the history of the Ospedale, its mission and its place in Siena, in particular its relation to the Duomo, also dedicated to Mary.[8] That said, the Ospedalelong sought to maintain its independence from the cathedral administration and the Commune took over the appointment of the rector shortly before the frescoes in the Pellegrinaio were commissioned.[9]

Lupi shows that the extravagant use of architecture in the frescoes—all but one centrally focused, and generally populated by the wealthy and priests tending to a few exemplary unfortunates—can be aligned with the values of dignity and magnificence promoted by the Ufficio dell’Ornato and traced by Lupi into the civic architecture of Siena. These values will have had their most immediate support from Alberti’s affiliation of architectural beauty and good government (e.g., On The Art of Building, VI.2-3; VII.1), and their celebration in the so-called ideal city stage sets will have stimulated the Sienese frescoes, conforming to Lupi’s perception of their theatrical qualities. In effect, the Pellegrinaio frescoes add the ethos of charitable works to the noble virtues of the Vitruvian Tragic Set, and conversely, a requalification of liturgy in terms of Humanist theatricality.

If the early Renaissance recovery of Hellenistic theatre (and its characteristic armature, the triple-arched scenae frons) offers a milieu midway between human and divine affairs, Lupi’s reading of the pictorial transformation of actual sites within the compass of the Ospedale may point to thematic aspirations beyond magnificence. For example, and again venturing into the ‘pictorial’, but aiming to illuminate why these artists were so interested in the spatiality of column-groups, we might look at the fresco by Priamo della Quercia (brother of Jacopo), Blessed Agostino Novello Hands the Habit to a Hospital Rector (Fig.4). The image takes advantage of the location of the Ospedale entrance directly across from that of the Duomo to confect a common ceremonial setting beneath a domed baldacchino that fuses the hospital with the Duomo, and fuses the early fourteenth century (the Ospedale statutes of Agostino Novello) with the mid-fifteenth (the year-long stay of Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg).[10]

The triple portal of the Duomo itself derives from the Roman triumphal arch, and would naturally align with a scenae frons, but Priamo splits the central portal in two, superimposing it upon the far arch of the baldacchino and filling the right bay with a niche containing the Virgin, the common dedicatee of the two edifices, fronted by an altar, so in fact a chapel. This introduces a highly unusual asymmetry, and the compression of foreground, middle ground and background horizons creates a frieze of virtual niches for Sienese citizen-worshippers, as if to offer elevation of a good pragmatic life into a status equivalent to the paradigmatic Mary. The violinist and lutist perched above the lateral arches—and possibly the three figures in the foreground dressed in the same white gowns singing the liturgy—suggest one might see here a visual analogue of the tactus of Renaissance musical theory. The tactus is concerned with the temporal organisation of Renaissance music, and in particular the tension between the rhythmic emphasis of the words (human) and the music (divine), reinterpreted in the fresco as the circumstantial disposition of figures with respect to the measures and hierarchy of the spatial structure. Such temporal symbolism is certainly present in the combined drama, ceremony and rite which comprises the foreground scene, enacted in both the time-out-of-time of such performances but also in two actual historical times (of Novello and Sigismund).[11]

These two times are marked, respectively, by the Gothic and Classic architectures (whose intricate dialogue here includes the spiral columns framing the Duomo portal imported to the edges of the baldacchino) animating the several choices of architectural or ornamental motif traced by Lupi. Moreover the moon and sun on either side of the baldacchino dome and Adam and Eve in the two lateral niches (anticipating Mary’s niche) promote the impression that the central repetition of the Ospedale insignia—a ladder, ‘scala’, to heaven—in the frame at the top (our realm) and centre (the realm of consummated meanings) is meant to set charitable deeds within a spatiality embodying the cosmic temporality of salvation. Since no members of the Trinity are depicted, one could also read the fresco as a reinterpretation of the theme of Our Lady of Mercy, in which the institutional and architectural apparatus takes the place of Mary’s cloak sheltering vulnerable Christians.

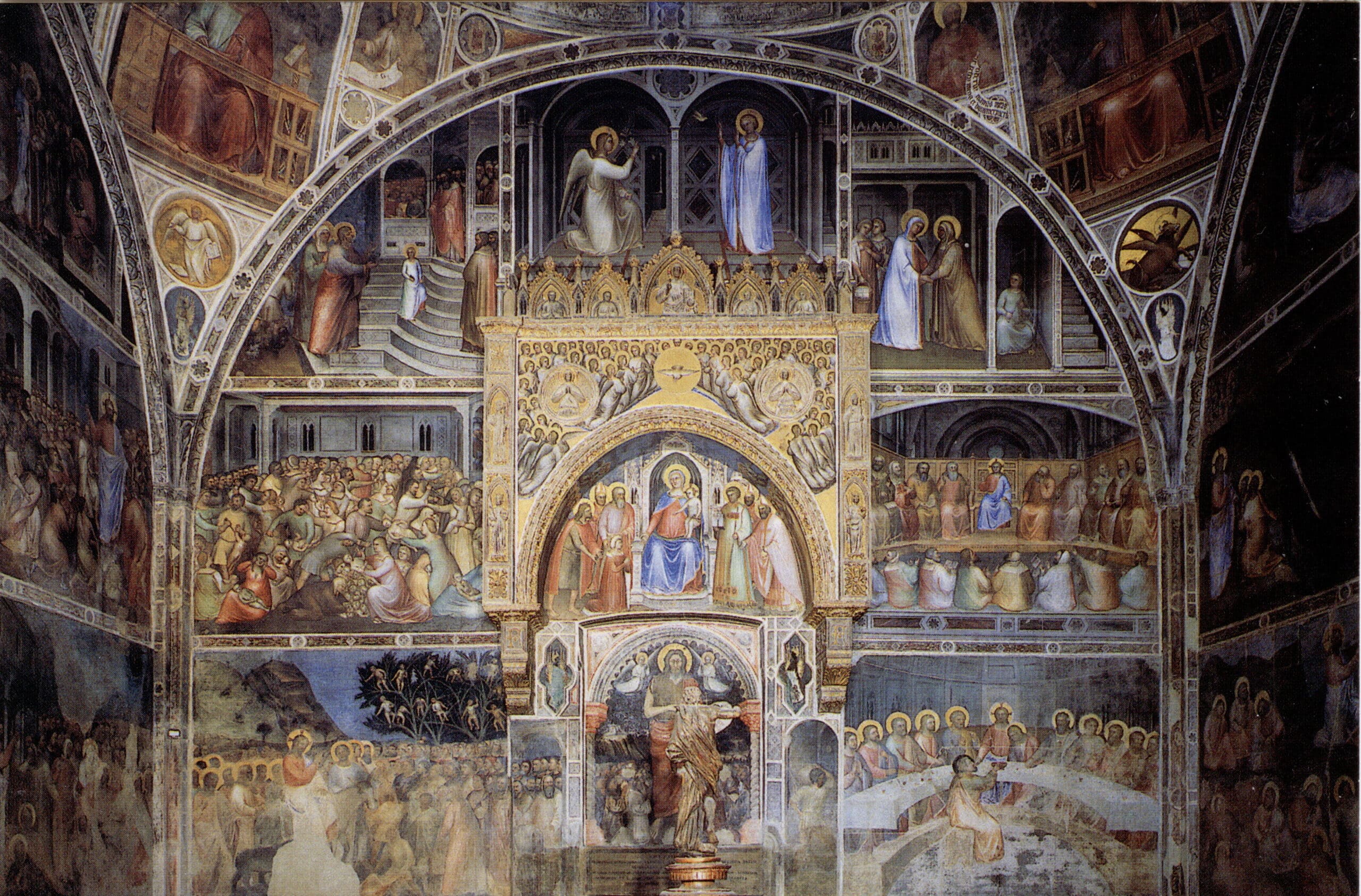

The Pellegrinaio frescoes were all constructed as if to be seen-through, in the manner of the Albertian ‘window’, perhaps intending to invite spectators to the staged dramas or even to include them among the represented people, even though the optimal viewpoint was elevated about two metres above the floor. Despite also being mounted above door-height, and clearly well-informed in the conventions of perspective-construction, the images of Lupi’s third case study, Fra Angelico’s frescoes for the Chapel of Pope Nicholas V (Fig.5) do not have the same quality of rhetorical engagement.[12] Executed only a few years later than the Pellegrinaio frescoes, the compartmentation and didactic intent surrounding the stories of Saint Stephen and St. Lawrence join the painted architecture to the narrative rather than to the spectator, somewhat reminiscent of late medieval practice such as Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel or his work at Assisi. Like Fra Angelico’s famous frescoes for San Marco, Florence, the images are vehicles of meditation, demanding an important remoteness, rather than spectacles embedded in this world. That said, Lupi is right to observe that Fra Angelico’s handling of architectural detail, its play between Vitruvian orthodoxy and invented heterodoxy, is closer to the precision of Michelozzo than to the more painterly speculations of, for example, Priamo della Quercia [note the capitals of Priamo’s baldacchino, as well as its two rear pilasters].[13]

Lupi’s decision to leave to one side the vexed question of the possible participation of Alberti in Nicholas V’s renovatio Romae is justified for what she gains by way of showing how his references come from several sources, some at the level of building type, some at the level of architectural ornament.[14] Much the way the two cycles proceed in parallel around the three walls of the chapel, Lupi sees a subtle exchange of references between the architecture associated with the earlier St. Stephen (Jerusalem) and the later St. Lawrence (Rome), informed by available archaeology. The ensemble aspires to evoke a possible contemporary Rome as a recovery of the time of origins associated with the two cities, oriented about the wise words of Stephen and the good deeds of Lawrence, instead of the conflicts which the return from Avignon in fact precipitated. Indeed, with regard to Lupi’s argument regarding the Chapel’s possible role in affirming papal legitimacy, the pope appears in only two of the St. Lawrence frescoes; and it might be offered that Fra Angelico provides an impetus for renovatio that is metaphoric, depending upon the ethos of the two saints reflected in the decorum of the other actors, set in an architecture that is at once actual and symbolic and oriented around significant situations with the same two qualities. For Lupi, the architectural embodiment of these qualities arises from Fra Angelico’s command of the details and significance of Rome’s Classical heritage, thereby setting in motion the curious reciprocity of correctness and fantasy on behalf of an idealised historical past as the vehicle of a spiritual future that characterised the subsequent centuries of ‘renaissance’.[15]

Notes

- Livia Lupi, Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy: Innovation and Persuasion at the Intersection of Artistic and Architectural Practice (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2024), xvii.

- Lupi, 2–8.

- Livia Lupi, ‘The Rhetoric of Fictive Architecture: Copia and Amplificatio in Altichiero da Zevio’s Oratory of St. George, Padua,’ Architectural History, 60 (2017), 1–35.

- Amanda Lillie, ‘Constructing the Picture’, <https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/constructing-the-picture/introduction> [accessed 16 April 2025].

- Lupi, Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy, 39.

- Lupi, 153–165.

- A useful set of plans and sections of the complex topography of the Ospedale are readily accessed in Fulvio Irace’s review for Abitare 13, 2003, of the archaeological installation in the lower levels: <https://www.spaziolaboratorio.it/it/mimma_caldarola/pubblicazioni_13/abitare_2003.aspx#&gid=1&pid=1> [accessed 16 April 2025].

- Lupi, 55.

- J. H. Baron, ‘The Hospital Of Santa Maria Della Scala, Siena, 1090-1990’, BMJ: British Medical Journal, Vol. 301, No. 6766 (Dec. 22–29, 1990), 1449-1451.

- Lupi, Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy, 92–94.

- The richly-clothed anonymous kneeling figure in the foreground is the rector, generally a wealthy individual who upon election would surrender his worldly goods to the institution, represented by Agostino Novello handing him a cloak of poverty, in accordance with his statutes. Agostino Novello—’the new Augustine’—is called ‘blessed’ because he was esteemed a local saint, in the custom of the time (recognised by the Vatican in the eighteenth century). It is tempting to see the figure on the far right as the old Augustine, in light of his occasional representation with a similar beard and cloak, reverting here from his customary paradigmatic existence to a pragmatic one. Lupi identifies the figure behind the rector as Emperor Sigismund, which must be correct.

- Located in the Tower of Innocent III (ruled 1198-1216), now embedded in the NW corner of the Cortile del Pappagallo of the Vatican Palace.

- Lupi, Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy, 116.

- Lupi, 104–7.

- Lupi, 140.

Peter Carl received his MArch from Princeton in 1971 and the Prix de Rome in 1974. He has taught design and graduate research at the University of Kentucky (for 3 years), the University of Cambridge (for 30 years), and London Metropolitan University (for 7 years), and has held visiting positions at Rice University, University of Pennsylvania, Cornell University, and Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is currently studying metaphor and embodiment as the basis for the architectural poetics by which situations are reconciled with technology, ethics, mood, reference, etc.