Writing Prize 2021: Reading Material

This is a narrative of listening: listening to materials, processes, place and self.

When you sit in a room and read a book you are not looking at your environment – you perceive, touch, and smell its atmosphere and presence. Inadvertently, you register the space that surrounds you.

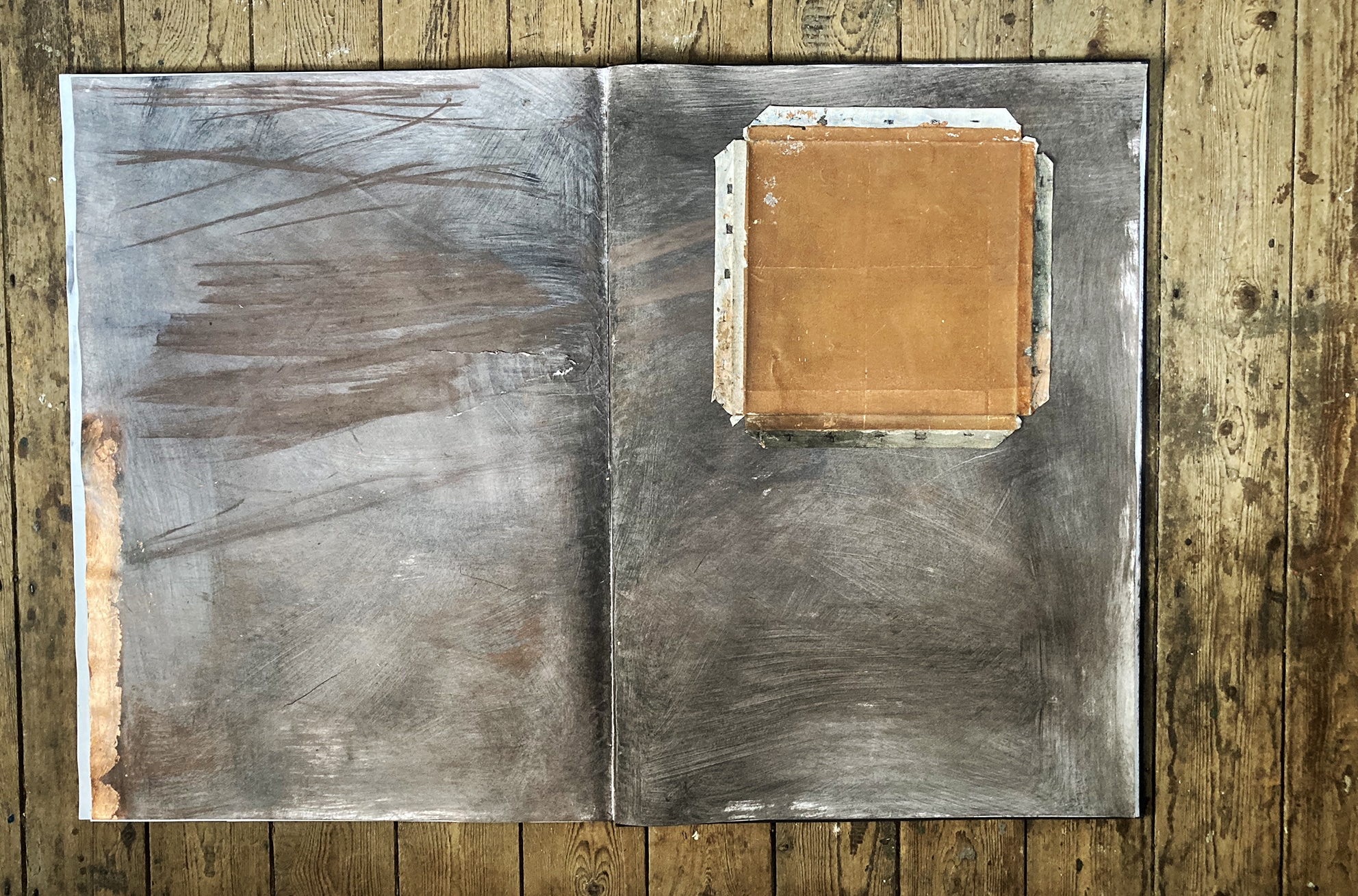

During the initial lockdown, I commenced a reflective process of drawing to document an intimate reading of a live-work space. The building was appropriated from a dilapidated workshop, a palimpsest of worn surfaces, with peeling layers of paint and oil stains. I asked myself: can I document what makes this space meaningful? Can I evidence elusive notions of resonance?

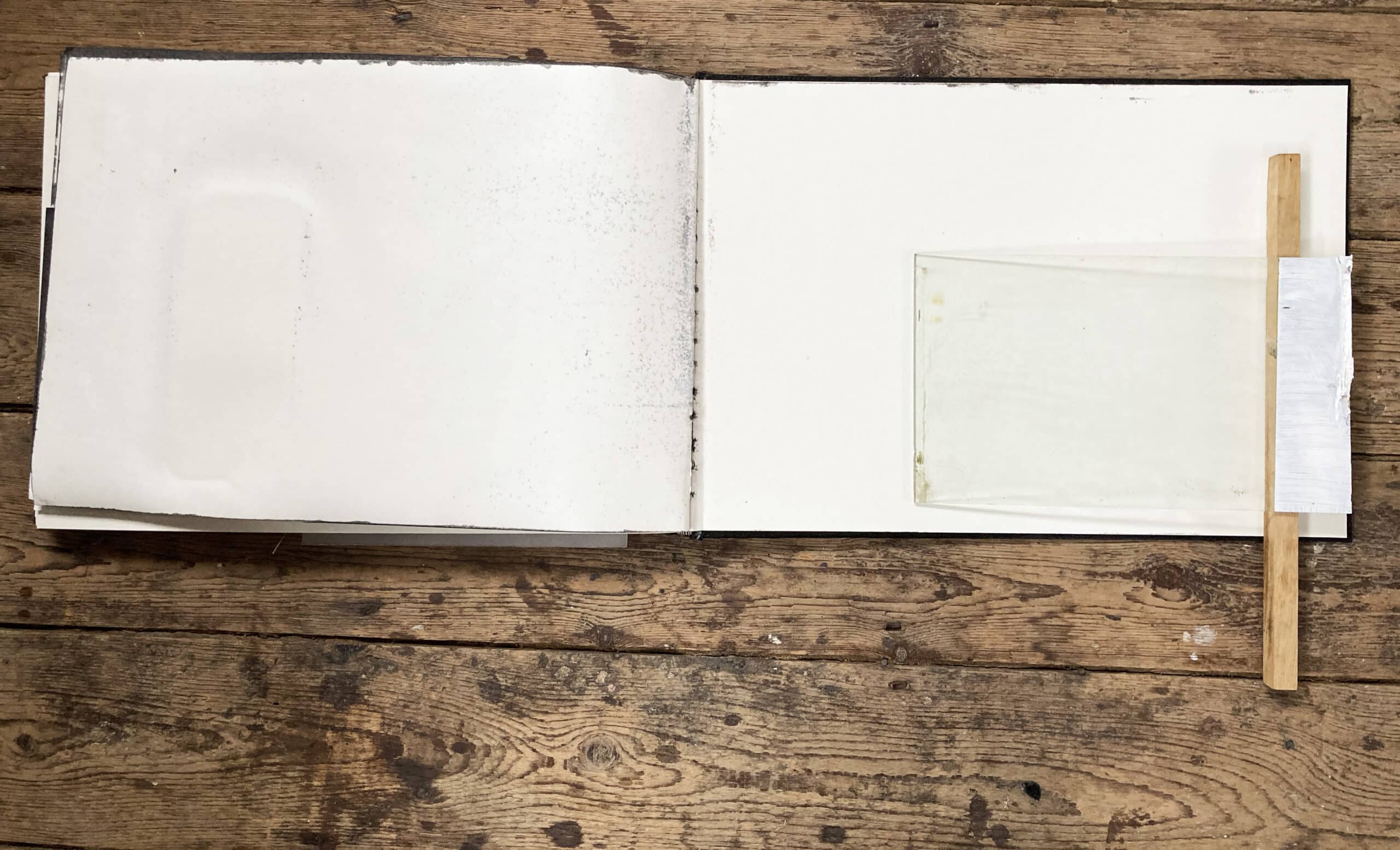

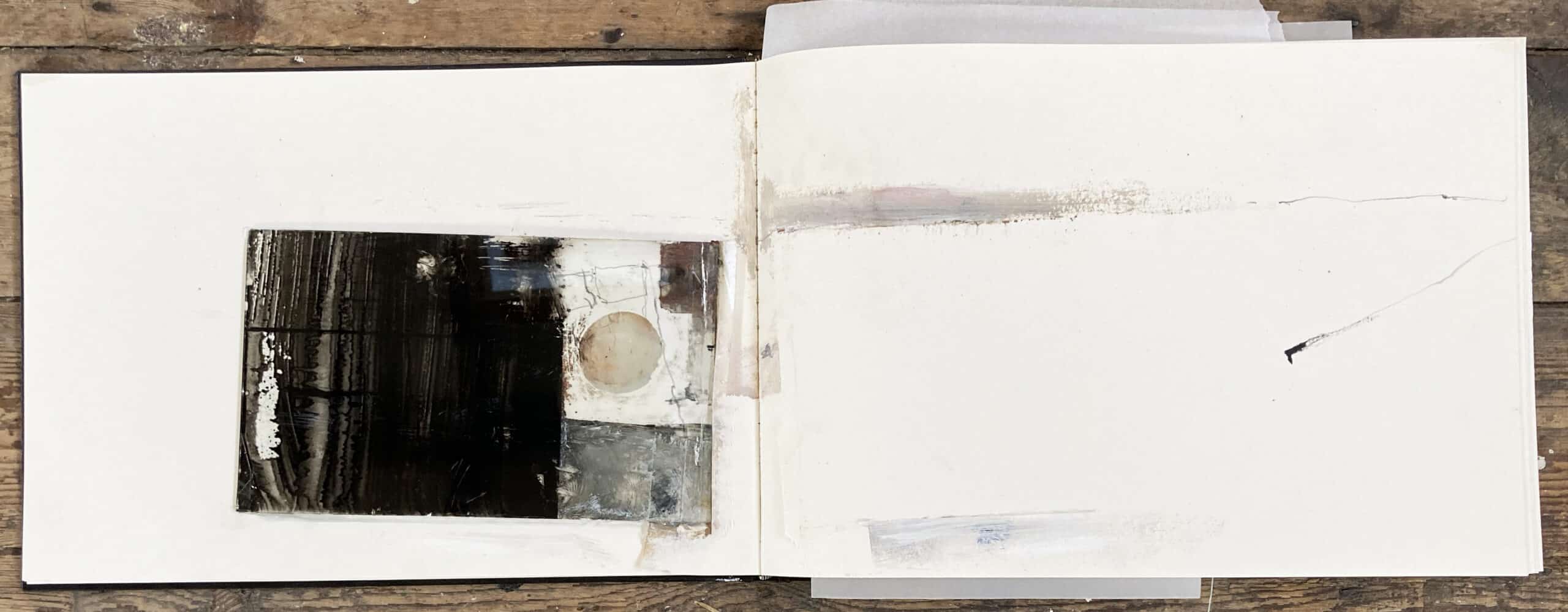

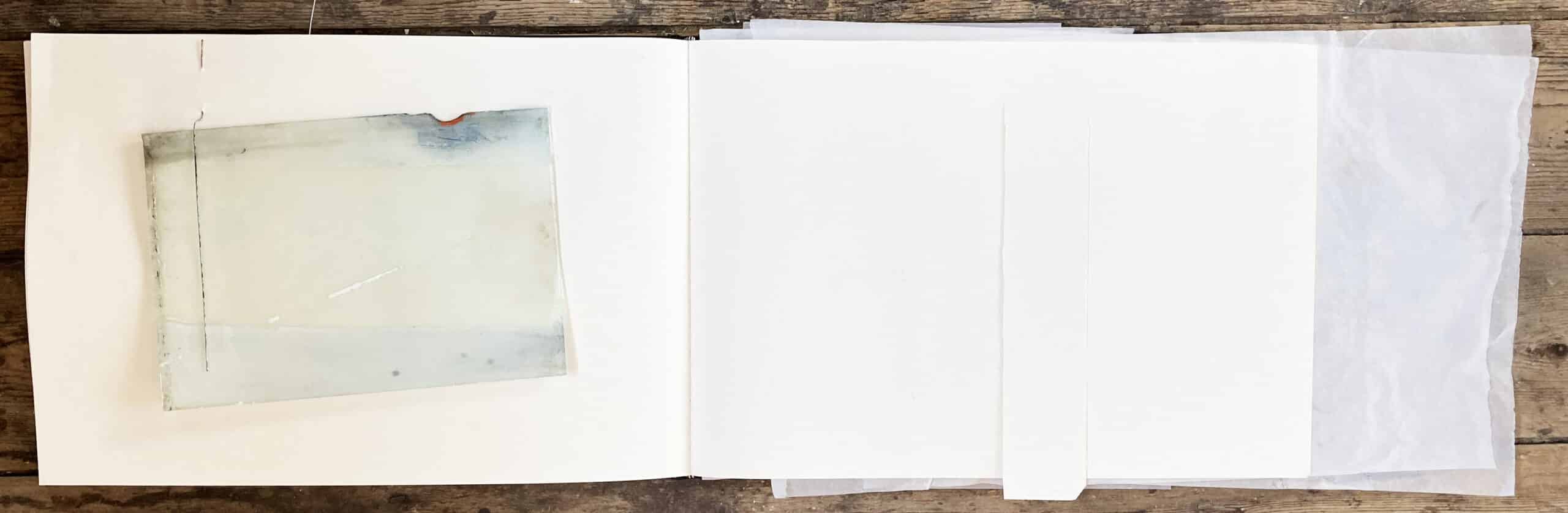

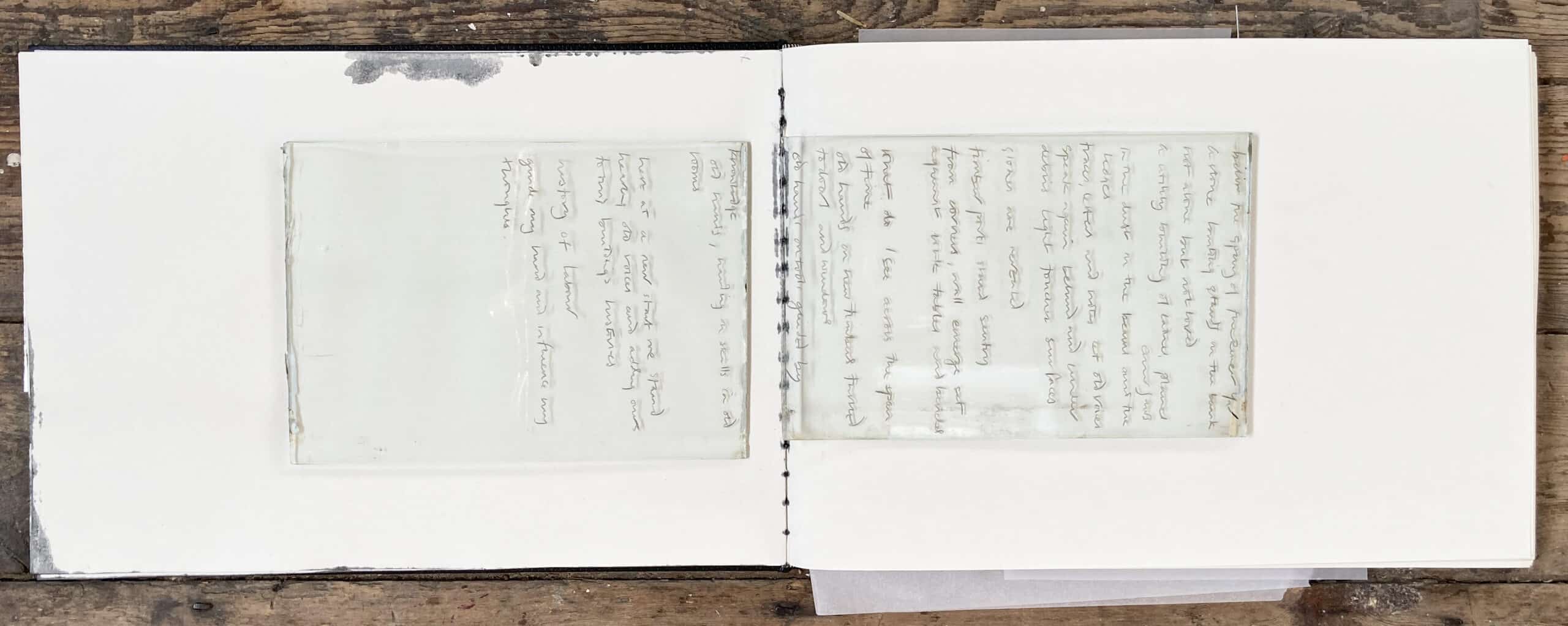

I searched for moments, listened acutely to that which filters into my interior, and used drawing as an instrument to document unconscious thoughts and feelings that make this space my ‘oneiric house of dreams.’ [1] I accepted a state of unknowing, ‘drawing is thus a depicting, a hauling, an unravelling and being impelled towards something.’ [2] And I predetermined only one factor, that the drawings would begin from a found object: a collection of thin pieces of old window glass from the original site.

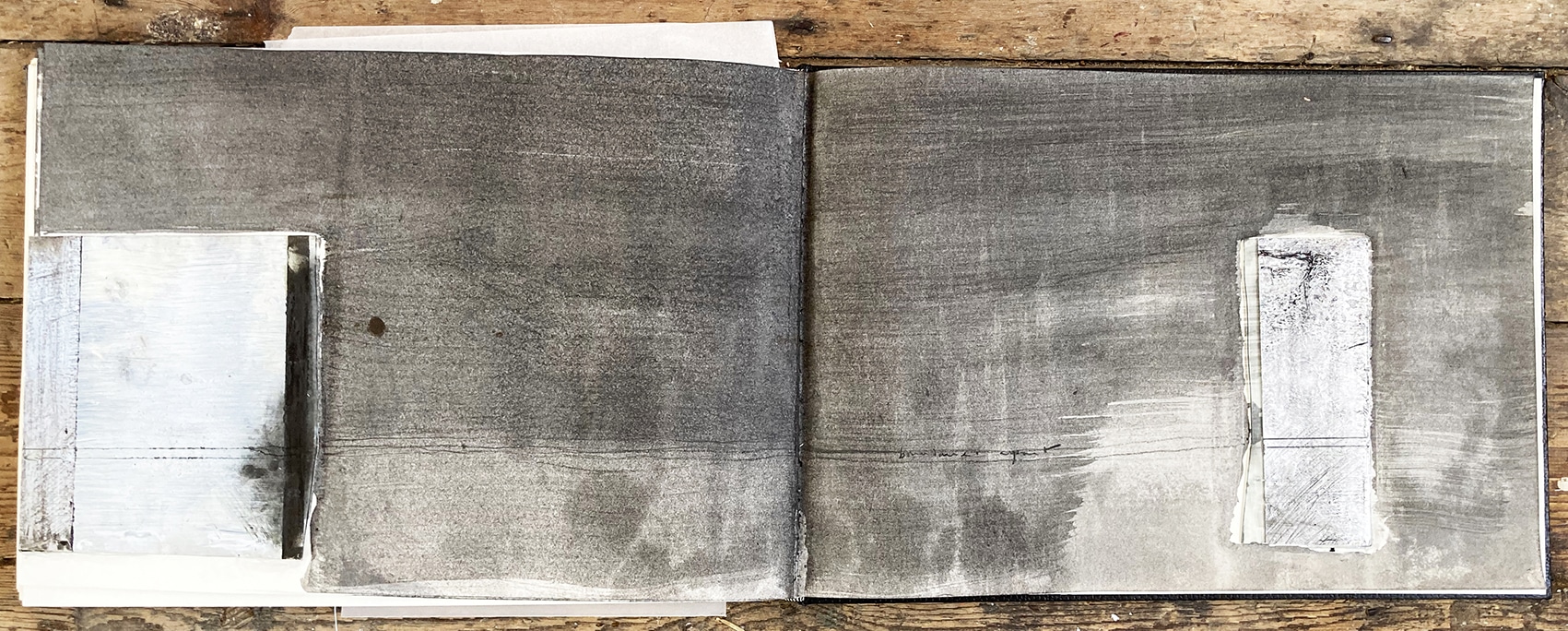

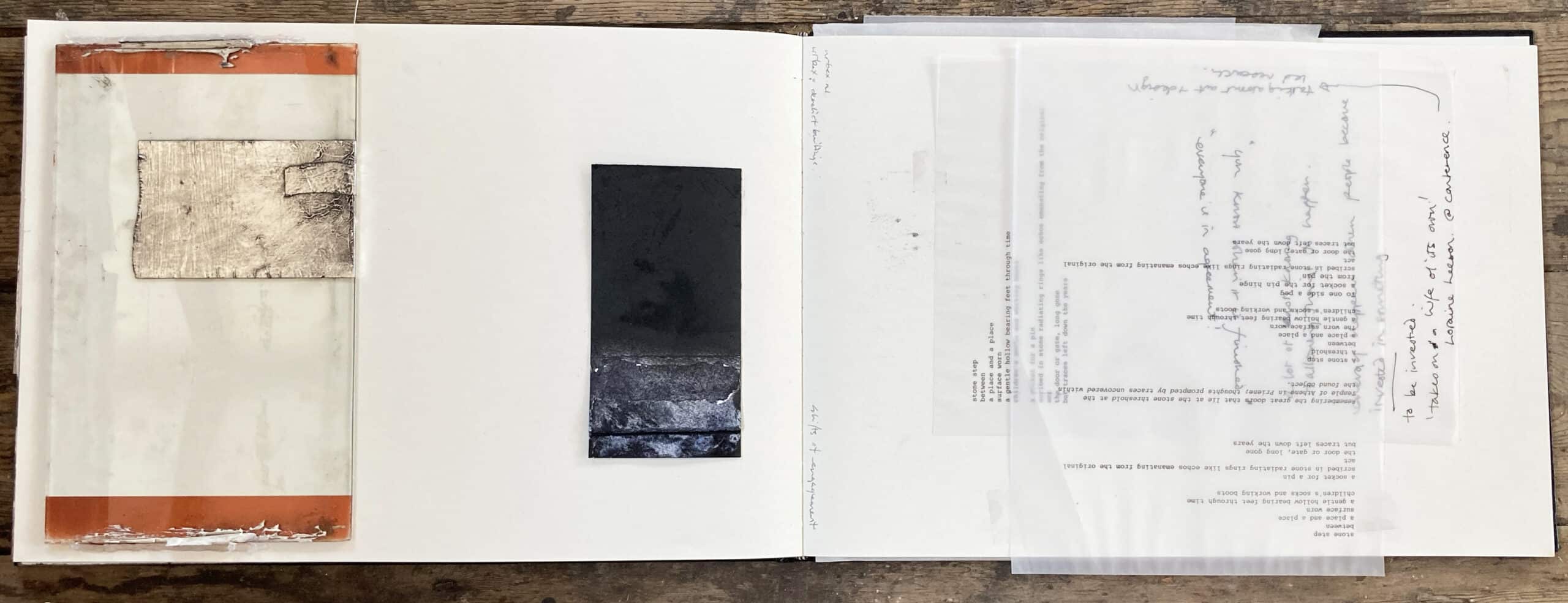

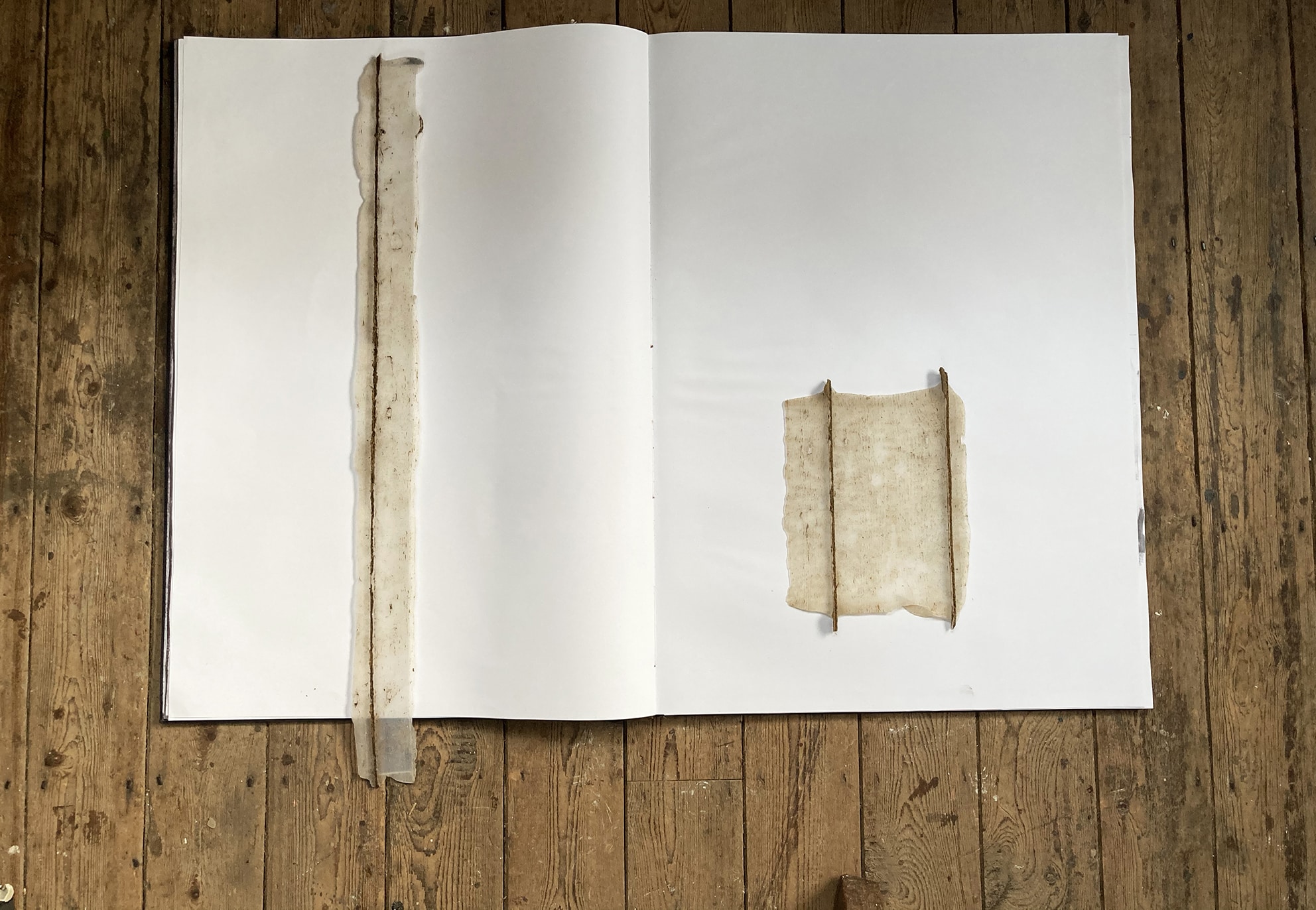

These found elements are not neutral participants, for they offer a state of contingency: resistance, minor slips, scrapes, transparent overlays. They are utterances that fuel perception. The old panes were originally scored and cut by hand, indicated by the chips and errant cutouts that trace their edges. Putty is overlaid with stained white mastic, and discolouration, bearing their own patina of time. Fragile, these canvasses bring with them a sense of care: care in handling, positioning and recollection. I gathered a range of mark-making materials; colours and odours that are redolent within the space; white paint, black paint, dark brown charcoal, fire grate polish, copper, lead sheet, sealant and casting silicone. The panes of glass were stacked, the work surface cleaned and the tools laid out. Brushes, clay and different types of paper – trace, card and watercolour –, graphite, charcoal and different grades of wire and cloth. The materials were implicated in this activity to induce thought, imagination and insight.

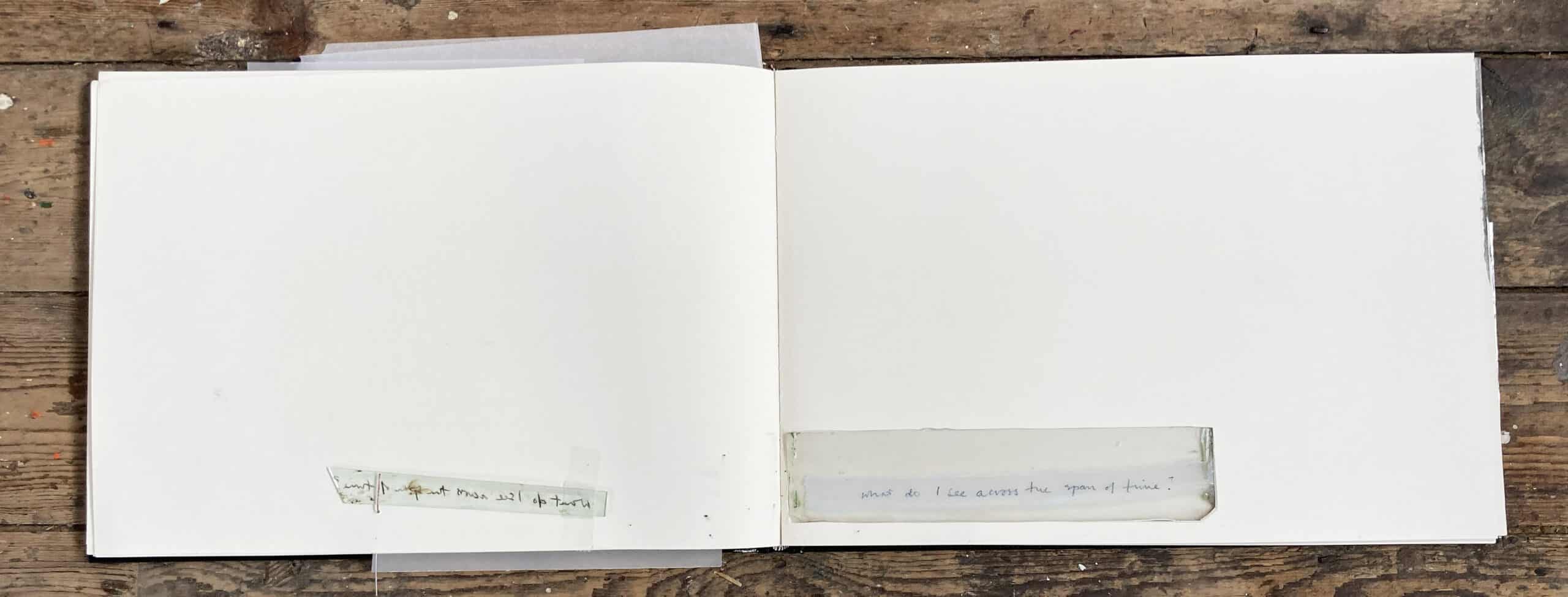

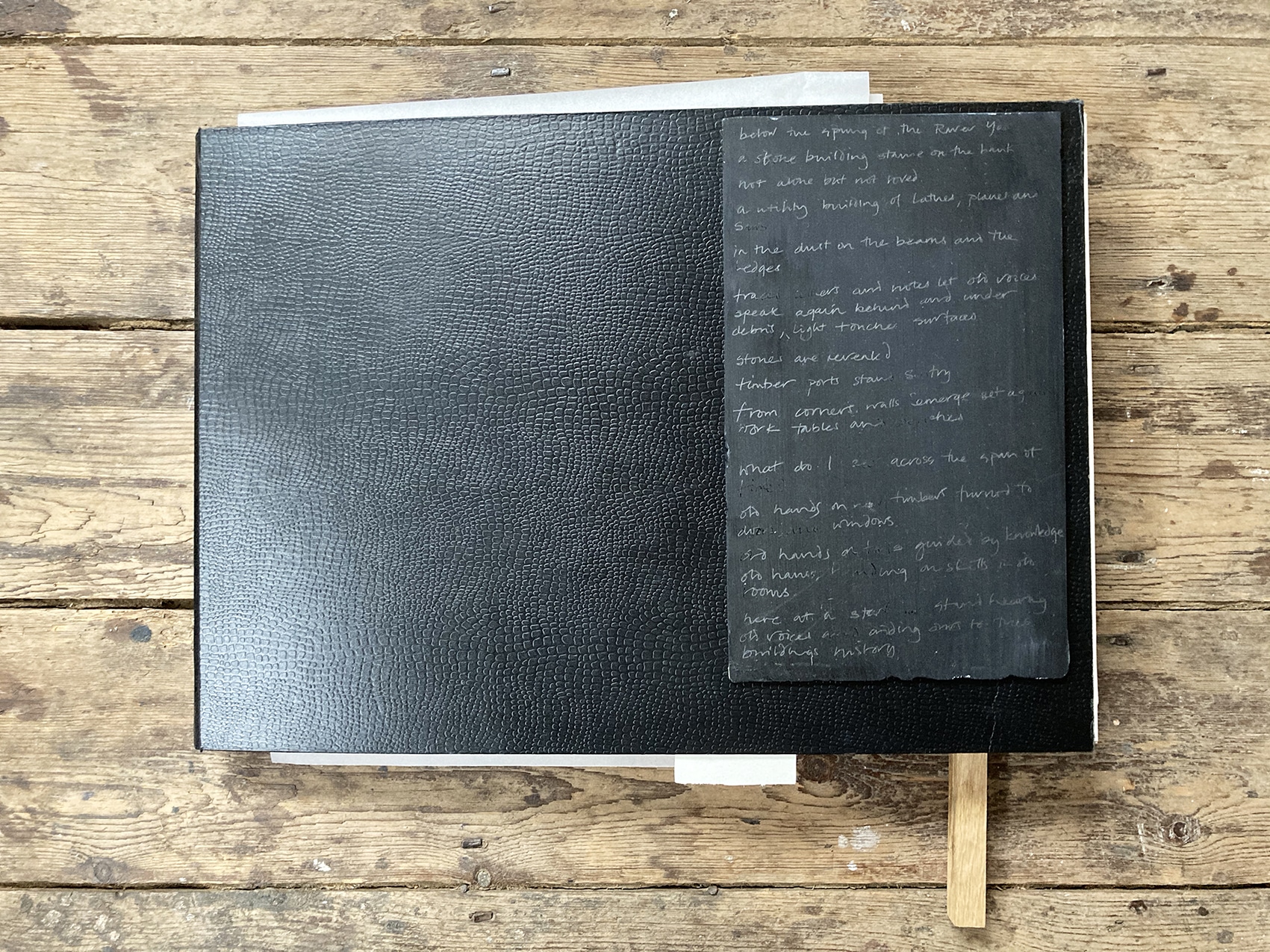

In addition to these tools are simple compositions of text, prompted by old letters unearthed on-site during the building works. They are simple linguistic compositions that try to capture the essence of matter. The words accrued from the direct observation of residual traces. Look, again, at the hinges on a former door, its weight scored deep in the threshold, or a wooden template pinned to the wall, untouched. Now observed and valued, embodied in the drawings where gesture and word sit side-by-side, they are reconsidered.

The sketchbook was a conscious decision to counter internal censorship or judgement that might inhibit or edit the drawings. The jacket can close, allowing gestures and mark-making to retreat; and it is also a landscape, a spatial territory with contested edges, where a composition starts and ends are in question.

Initial marks were figurative and focused on objects in near sight. Overworked but nascent, they helped instigate thought and fine-tune the eye.

I saw subtle shadows created by the text on the glass as it lifted off the page. These ephemeral glimpses of duplicated words were like ghostly voices that disappeared when the sketchbook closed. They spoke about the diurnal nature of the light within this building as instances appear and recede throughout the day.

Words can be edited, but not drawings on glass. The surface reveals brushstrokes from either side, and the echoes of its earlier use began to determine lines of orientation in the drawings. This medium builds in its environs by consuming reflections. Black paint creates a momentary camera obscura effect to show an inverted world. When positioned next to windows, one notices subtle inflexions, movements of light and shade, and slight distortions in the old rafters bowed through the weight of time. The timber floor is bone dry, purposely bearing no wax or stain, it retains its original colours. Silicone casts on the floor are soft and flexible like skin, and reveal scars and gouges on this utilitarian surface; years and years of impact. The casts also preserve layers of dust, trapped in crevices, and the aromas of previous tenants.

There is disquiet to this process, intuitively trying to anticipate what might be required to achieve just the right gesture. From experience, I knew that it was important to dispense with all other encumbrances. Searching for a particular pen or colour could open the gate to capriciousness. It is the nature of a drawing that it can easily fall foul and become mechanical and predictable. Intensity is important, visual acuity and agility of thought. At no point can a sense of value or preciousness creep in and disable your instincts. I must assume the role of a covert bystander: alert, apparently disinterested, but attentive and ready to act. A lapse in concentration lets serendipitous clues pass by undetected. If focus is lost, the author is repositioned as the technician.

I used this time to search for a new reading of my home; a space that could offer an ‘exchange’ between building and occupant. When this dialogue became most evident, I was able to make swift and decisive decisions; juxtaposition of mark, materiality and placement. ‘I think we are always searching for something hidden or merely potential or hypothetical following its traces whenever they appear on the surface.’ [3] Without mimicry, these studies evoke the textures and rhythm of marks of habitual use and the absences that still prevail. Through this practice, I have re-witnessed the conjecture of a white paintbrush carelessly cleaned on the old interior cladding, dark rusty stains imprinted on the underside of beams or empty sockets for timber joists in the stone spine wall; qualities that sit at the edge of our perception, things that are here and not seen.

These emergent set of drawings consolidate my thoughts, ‘thinking through making, almost as if the fingertips bear a direct nuanced correspondence to mind, memory and thought.’ [4] The genius loci is potent within these drawings. The marks reveal an empathetic bond. They document a tacit reading of material, space and time that is pertinent to me, shoring up my sense of identity. This is a space for making, for doing, not a staged backdrop. The honesty of its histories sits comfortably alongside my own, providing a stable sense of continuity and therefore meaning in these unexpected times.

Rebecca Disney, MA RCA FHEA, is Senior Lecturer and Module Leader on the Interior Architecture programme at Middlesex University, alongside professional practice as Design Director with Lanyon Hogg Architects.

This text was selected as the winning entry in the General Autograph category of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2021.

Notes

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics Of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994 [1958])

- Michael Taussig, I Swear I Saw This (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), xii.

- Italo Calvino, Six Memos For The Next Millennium (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 77.

- Christopher Bardt, Material and Mind (London: MIT Press, 2019), 63.