Steeling Stirling & Gowan’s Isle of Wight House

The editors were thrilled to receive this response from Neil Jackson to our publication of drawings and literature relating to Stirling & Gowan’s Isle of Wight house. We are always interested in receiving comments and feedback from our readers: editors@drawingmatter.org.

In taking the plan of the Stirling & Gowan’s Isle of Wight house for the 1961 Daphne House in Hillsborough, California, Craig Ellwood might be accused of steeling the idea (sorry, bad pun). But this would be unfair. I would suggest that James Stirling probably gave it to him.

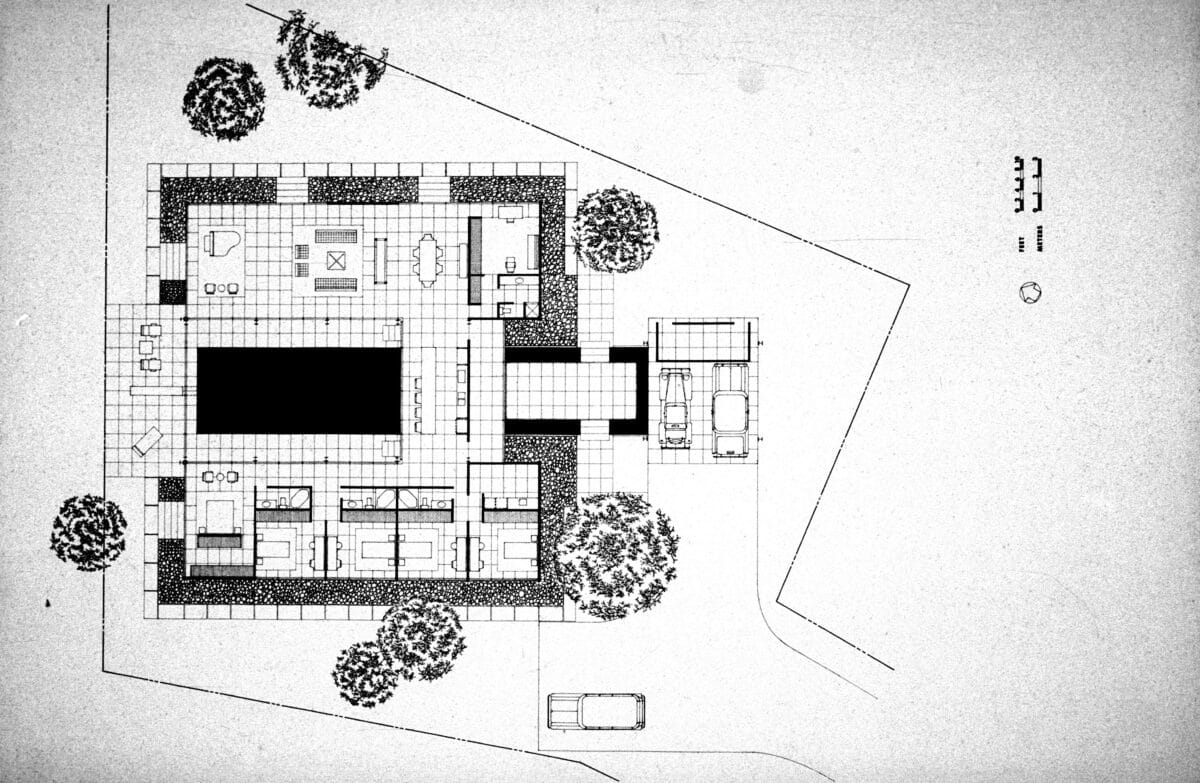

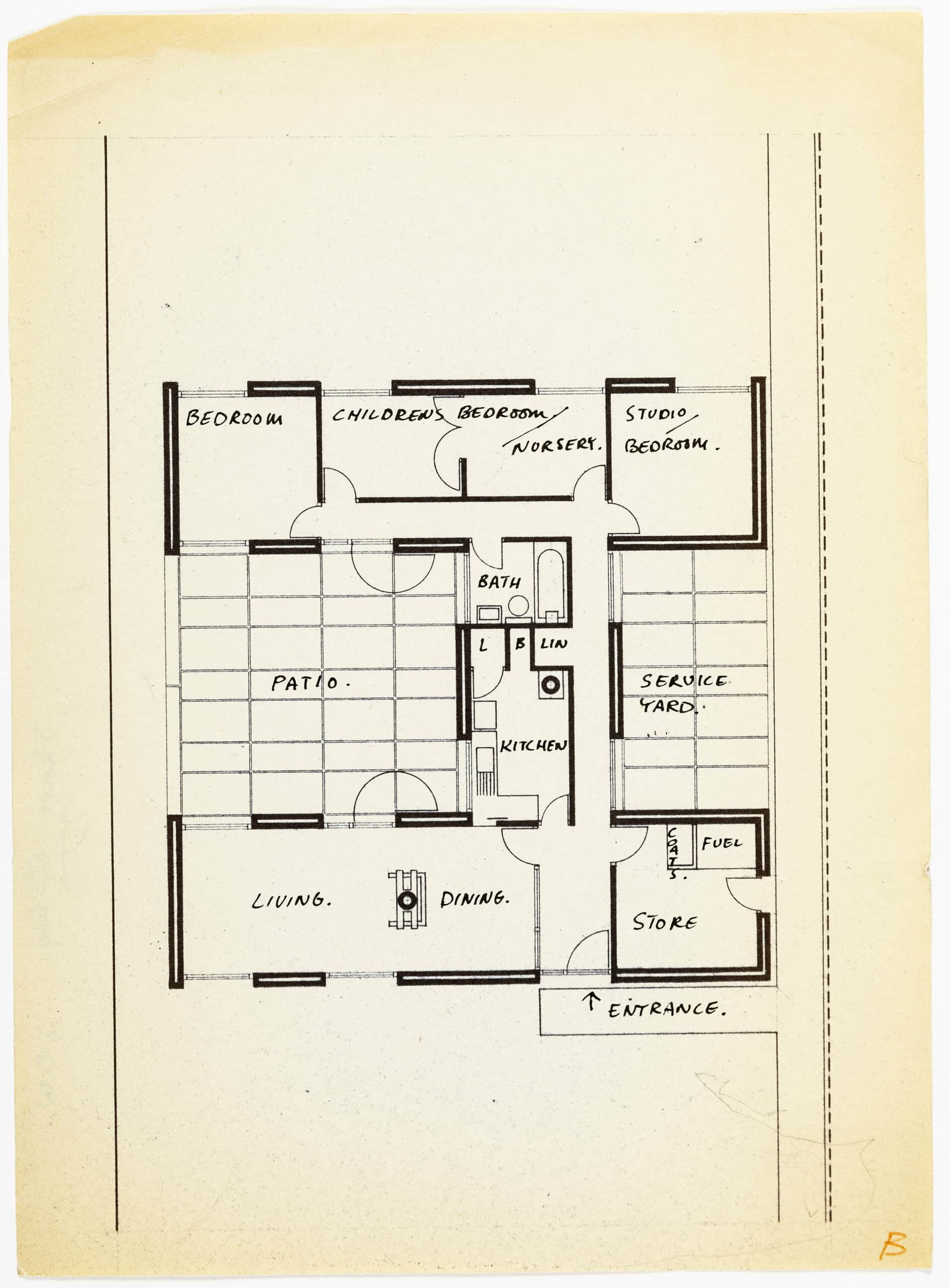

That the plans of the two houses are similar, if not identical, is undeniable except that one is a handed version of the other. Both are H-plans, the bridge between the two wings being off-centre, creating two imbalanced courtyards. Whereas Stirling & Gowan simply paved their larger courtyard, Ellwood placed a swimming pool in his. Stirling & Gowan’s open-plan living-room takes up the west wing flanking the larger courtyard, while Ellwood’s takes up the east wing. Both living-rooms have a free-standing fireplace, separating the sitting area from the dining area. In the opposite, bedroom wing, both houses employ an edge corridor along the courtyard side, linking the end bedrooms and skirting the central ones. Similarly, in each house the bridge between the two opposing wings accommodates the kitchen although Stirling & Gowan squeezed in a bathroom here too. Where the plans do differ is in their entrances. Stirling & Gowan positioned their entrance on one side, creating a hallway between the dining area and a storeroom: Ellwood simply extended the living-room so that the dining area absorbed this space. By contrast, Ellwood’s entrance is on the central axis of the H-plan, leading from the smaller courtyard to an entrance hall screened by the back wall of the kitchen.

The other great difference, of course, is that one building is constructed of load-bearing brick wall-panels while the other employs an exposed steel frame, painted white.

So why should James Stirling have given this plan to Craig Ellwood? Although Ellwood certainly kept an eye on European architectural publications, ensuring that his buildings received frequent exposure, it is unlikely that he would have seen J. M. Richard’s review of the Stirling & Gowan building in The Architects’ Journal of 24 July 1958. In November and December 1959, Ellwood had taken up an appointment as a Visiting Critic at Yale, an opportunity which represented itself again the following January. It was here that he met James Stirling, for the two were allocated the same office. The students referred to these two visitors as ‘the thick man’ and ‘the thin man’ on account of both their architecture and their physical appearance. Both were heavy drinkers: Gibson Danes, the Dean at Yale, wrote to Ellwood that February, ‘I hear that since you and Jim left the East Coast the gin is stockpiling like crazy, and the olives, Man, warehouses are loaded …’. In October 1961, Ellwood wrote to Danes from Los Angeles: ‘Jim Stirling is here now and is trying to talk me into New Haven November 18 and 19. Is Yale ready for another round of Mr Thick and Mr Thin? You’d better alert the Campus Police.’

Meanwhile Nicholas Daphne, a San Francisco mortician with a site in Hillsborough, California, wanted a house. He had first approached Frank Lloyd Wright, who had previously designed a circular mortuary for him, but once he saw Ellwood’s Case Study House 16, he appointed him. Although Jerrold Lomax, an Associate in the office, later said, ‘The layout was pretty much my design’, Daphne’s widow Virginia recalled Ellwood supervising the building. ‘He was a joy to work with,’ she said.

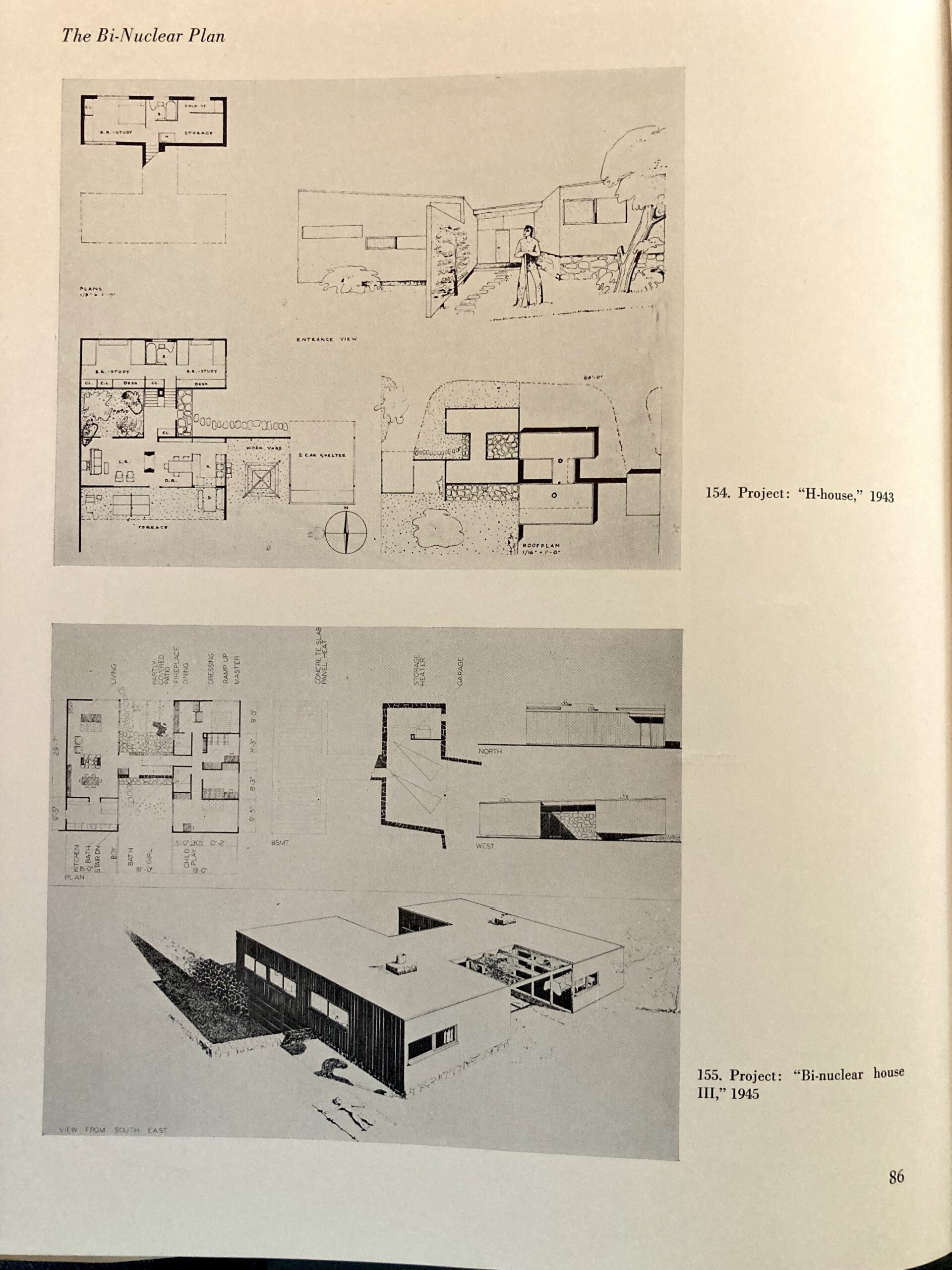

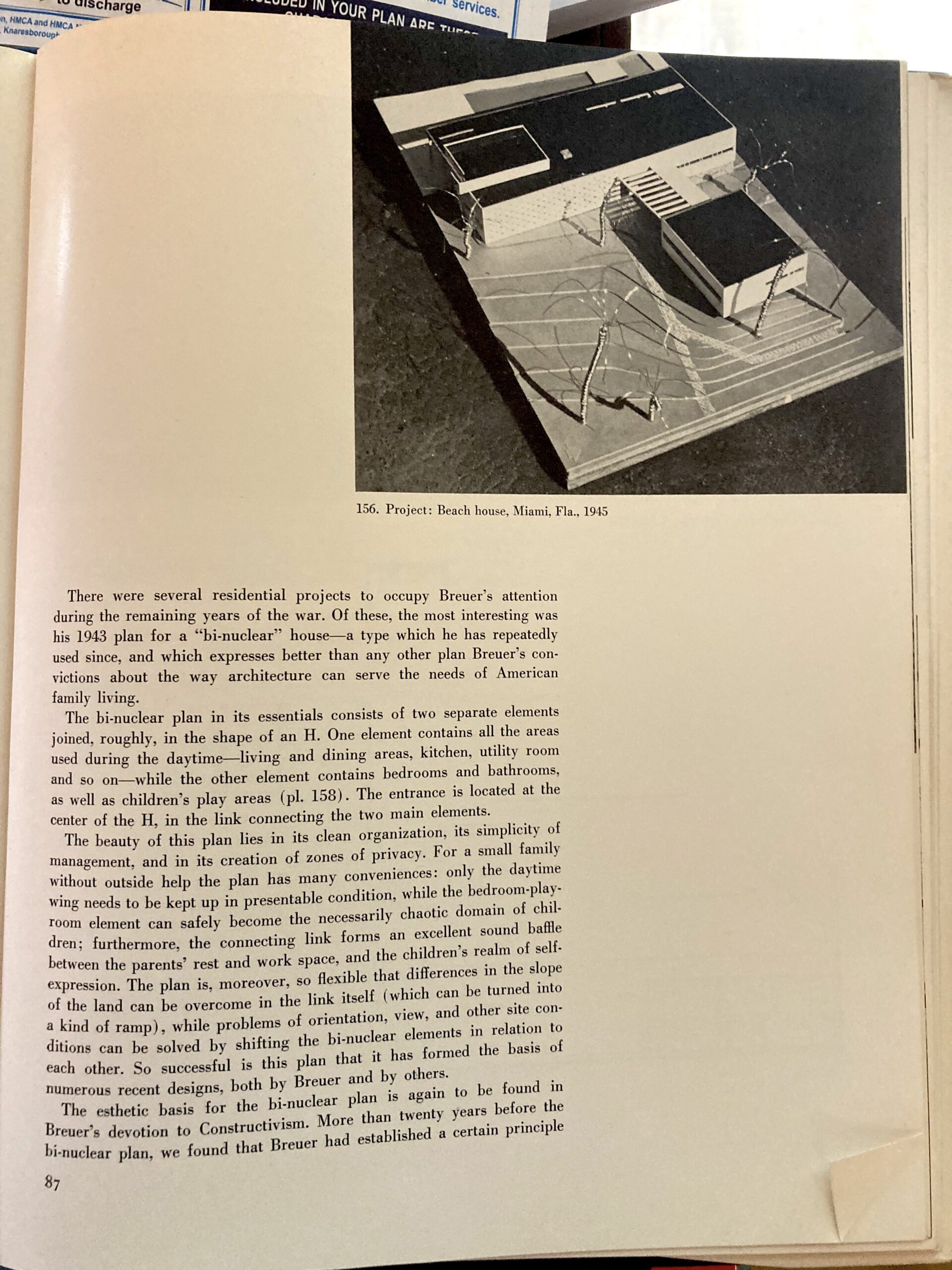

Ellwood was very good at the detailing and the fitting out of the buildings, but the design concept was not something that came easily to him. He always worked with others although he did not always credit them. Whether or not Lomax originated the design of the Daphne House is questionable: the H-plan had already been used by Marcel Breuer in his ‘H-house’ and ‘Bi-nuclear house III’ projects of 1943 and 1945 and had been published in Peter Blake’s 1949 book on Breuer. However, the Daphne House was designed at just the time that Ellwood and Stirling were consuming quantities of gin at Yale and later, again, in California. The plan of the Daphne House is just too similar to that of the Stirling & Gowan house on the Isle of Wight for it to be a coincidence. Is it not possible that the Daphne House originated as a sketch on a barroom napkin which Ellwood, lost for ideas, stuffed into his pocket and later gave to Lomax to work up?

Mr Thick and Mr Thin, for all their differences, made a good pair. It is ironic that they were to die within a month of each other in 1992. Progressive Architecture printed their obituaries side by side.

Quotations are from the author’s book, Craig Ellwood (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2002).

Addendum, 30 July 2021

There is, perhaps, a final twist to this story. The Isle of Wight House, as noted in Stirling & Gowan: The Isle of Wight House, was ‘an important early project by Gowan (although sometimes attributed instead to Stirling or to the pair together)’. Throughout this short piece I have credited the house to Stirling & Gowan: the plan shown here is inscribed on the verso, ‘James Stirling I.O.W’ and Stirling includes the house in his famous ‘black book’, James Stirling: Buildings and Projects 1950–1974, published in 1975. Indeed, the response to J. M. Richard’s review in The Architects’ Journal, published on 31 July 1958, was also credited to Stirling & Gowan. Yet, as Ellis Woodman’s interview with Gowan implies, it was Gowan, not Stirling, who originated the plan (see Stirling & Gowan: The Isle of Wight House). The house was for Gowan’s brother-in-law and, as he says there, ‘I worked on the details of the house at weekends at home so as not to intrude on office time.’ Yet the only real evidence for Gowan’s authorship is circumstantial at best, but it is found in a copy of Peter Blake’s 1949 book on Marcel Breuer, where the H-shape plan is illustrated. This particular copy, held in the Drawing Matter collection, is inscribed on the fly-leaf, ‘James Gowan’. Here the corner of page 87, facing the illustrations of the two H-plan houses, has been folded over, as if to mark the place. Stirling, of course, might have known this book, if not this actual copy, so was his offering of the H-plan house to Craig Ellwood a bit of a coals-to-Newcastle joke?