Sugimoto and Architecture

The early twentieth century saw a multifaceted blossoming of the avant-garde in Europe, with Dadaism, Futurism, Constructivism, De Stijl… These movements also had an influence on architecture. Until the nineteenth century, people’s way of living was centred around religion. Much architectural decoration was developed in order to express the magnificence of God. But with the dawn of the twentieth century, the power of religion was significantly eroded. Architects who wished to be in the vanguard had to explore what it meant to live in a world without God.

In this way, modernist architecture was born. Suddenly, decoration consisted in the absence of decoration, and being hard to live in was the definition of livability… In the short peace that prevailed after the First World War, brilliant minds like Le Corbusier, Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Giuseppe Terragni challenged one another, generating new ideas and new forms of expression. This was the new age of Fordist mass production and of Taylorism, which sought to optimise manufacturing processes by analysing and improving workflow. This was the age Le Corbusier had foreseen in a letter of 1917 when he spoke of ‘the terrifying but unavoidable life of tomorrow’.

I wanted to explore the unprecedented and never-repeated transformations that modernism wrought in our lives by revisiting its most monumental buildings. I used a large-format camera, but the pictures I took are out of focus. I achieved this blur by pushing the focal length to twice infinity. I see what I did in these terms: I tried to peek at a place that, being twice-infinity away, by rights should not exist, and I ended up with a blur for my pains.

The starting point for an architect is to imagine the ideal form of a building. He then refines his plans into architectural drawings and diagrams. Somehow, though, by the time construction gets underway, the original ideal has fallen through the cracks never to be seen again, like some doomed attempt to curb political donations. A building is the result of the ideal making a compromise with reality. The capacity to reject such compromises is proof of a first-class architect. A finished building, I like to say, is the tomb of architecture. Applying a focal length of twice infinity to these tombs reveals the soul of the building, whether dead or dying.

This text is excerpted from the catalogue of Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine, which was on show at the Hayward Gallery, London, 11 October 2023 – 07 January 2024, and is touring to UCCA Beijing and MCA Australia. Copies of the catalogue can be purchased here.

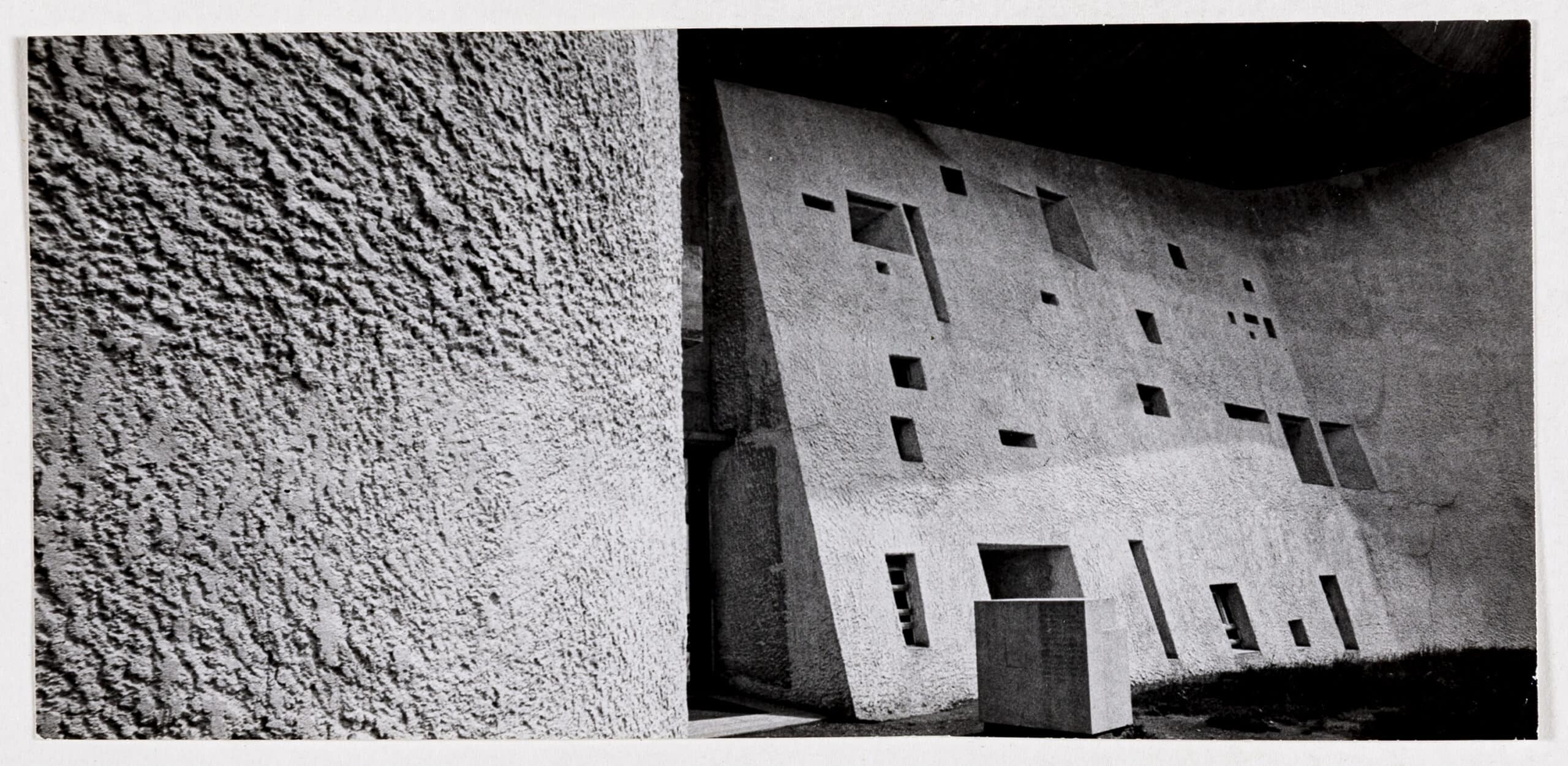

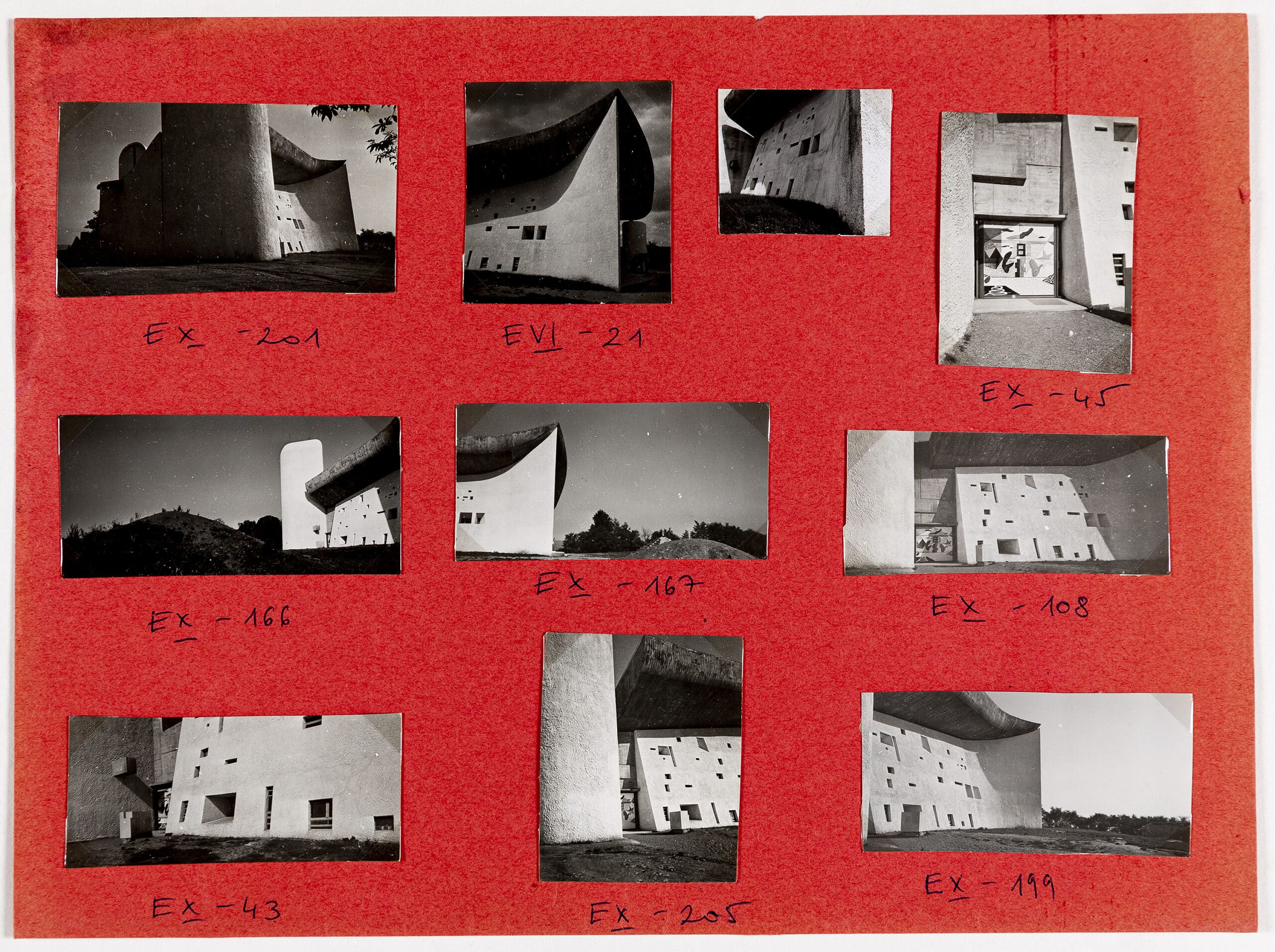

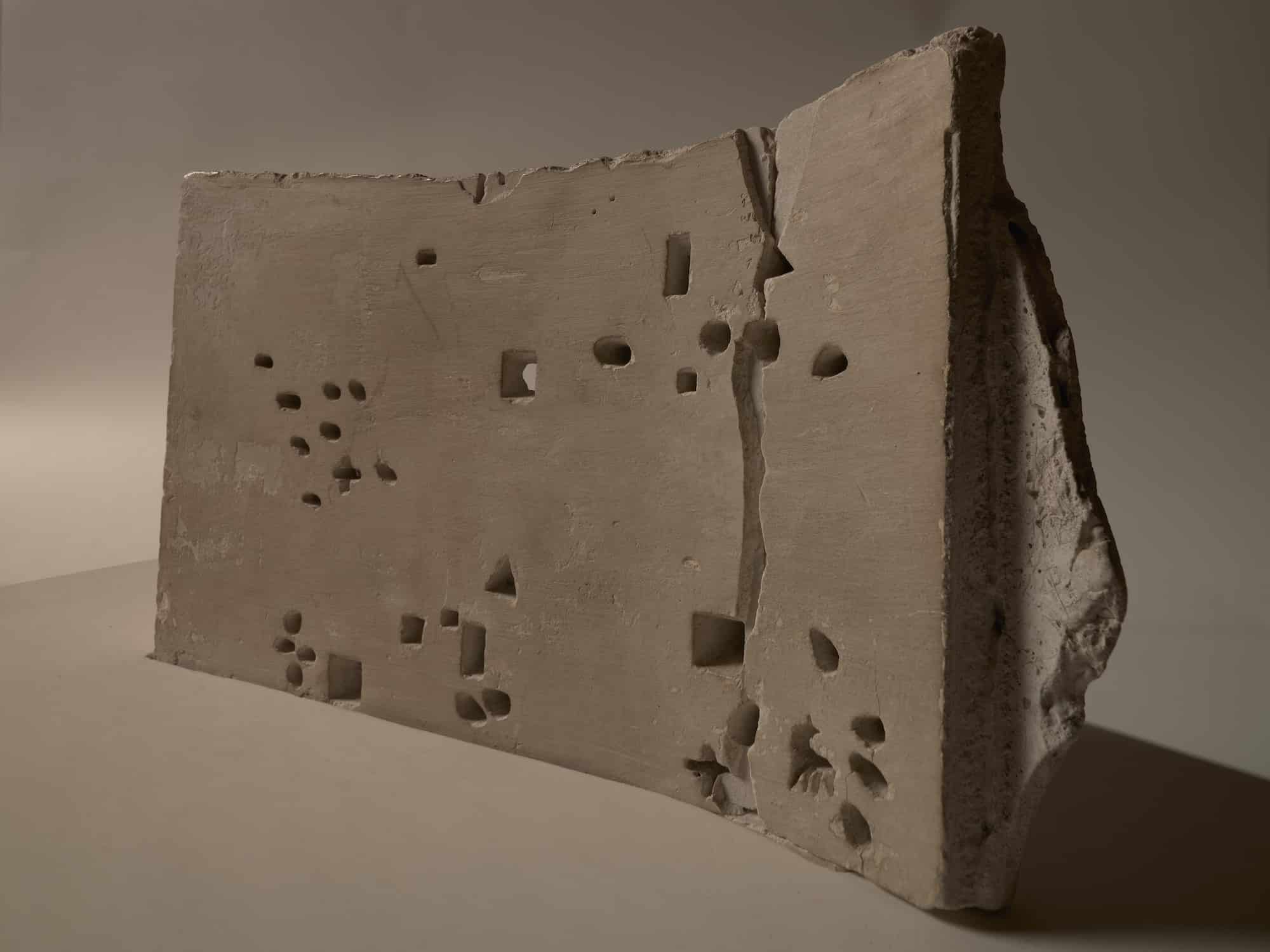

Editors’ note: from the archive, a new photograph of the model for Ronchamp and photographs by Lucien Hervé in the Drawing Matter collection; from a visitor to the archive, a poem by Pele Cox, first written to be read at a British School in Rome study day on Concrete in 2018 where it was performed by Vivien Lovell.