The Architect of Impossible Physics

More than once, when describing the processes involved in creating these drawings, my listener has responded with two words in particular: loading and channelling. I thought I would and should elaborate.

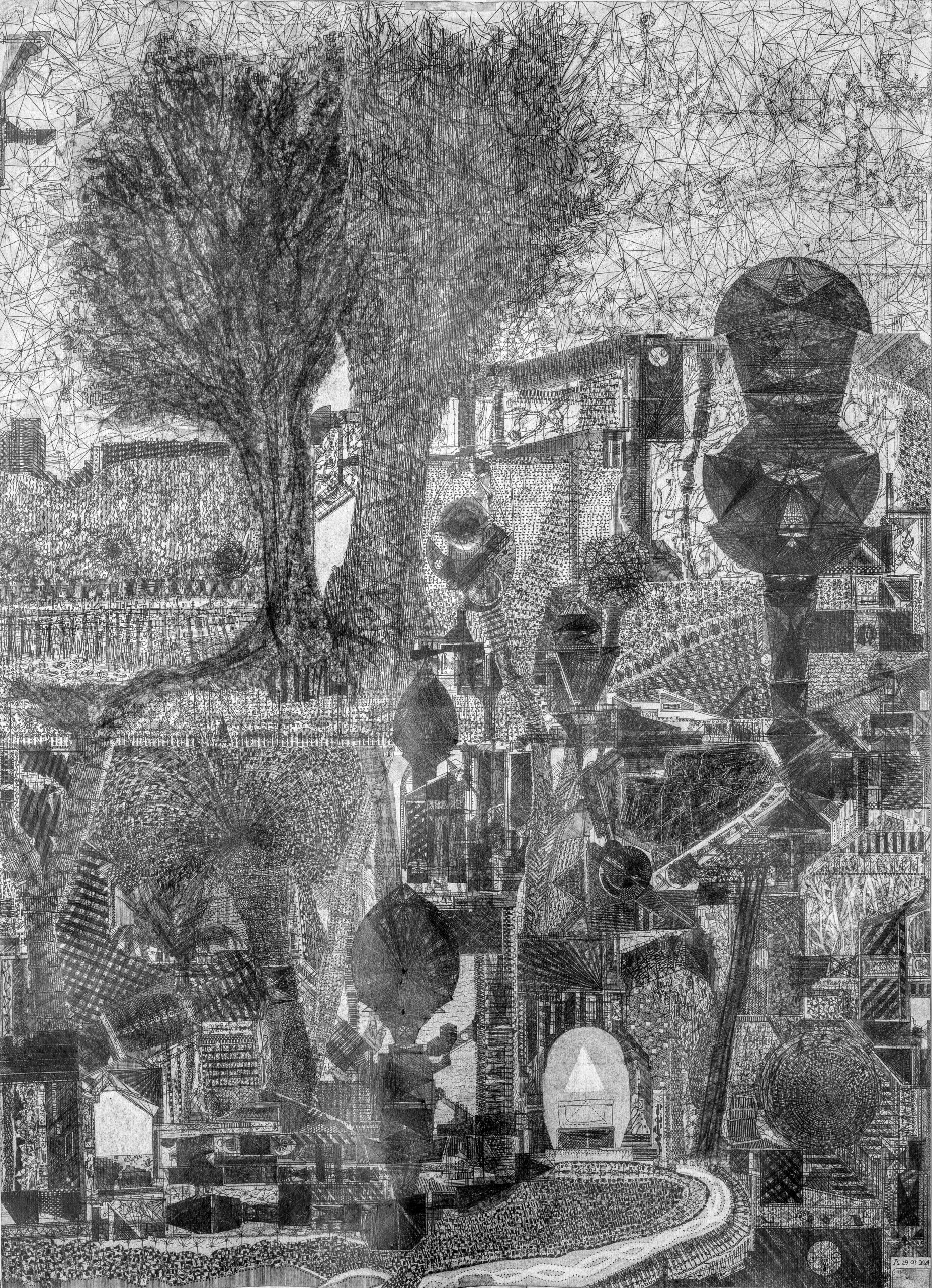

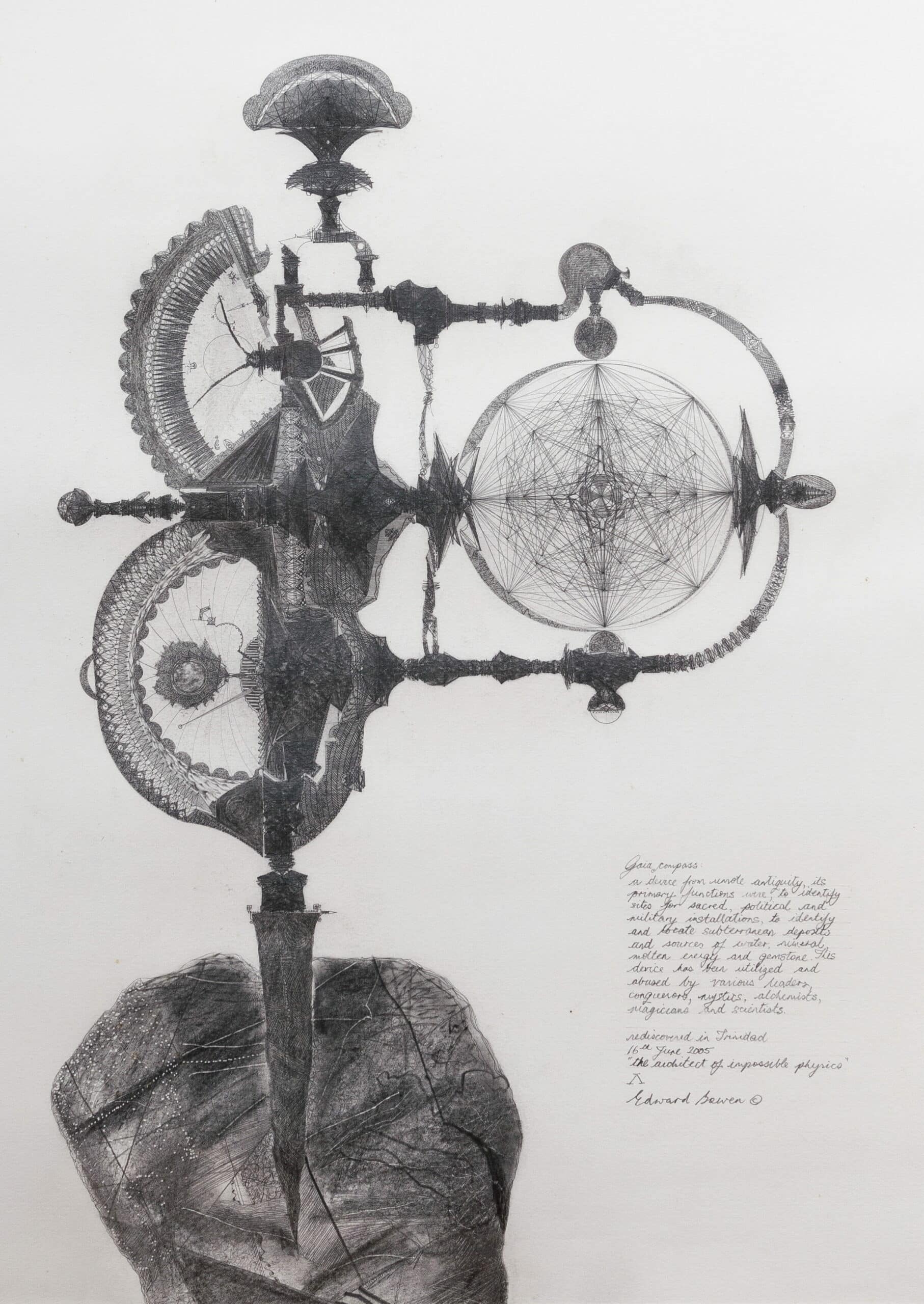

The initial first gestures, lines, squiggles, scratches, smudges and randomisations of the mark making inform the start to the work in these drawings—marks made deliberately as if a bee had alighted on the surface, its feet covered in magical and microscopic pollen dust. The first marks cut the white surface, with the intention that some drama or more information will follow. That first graphite information sits in an almost microscopic layer on the surface of the page, and that contradiction does not end there. From these initial moments, the mind wants, craves the creation of recognisable gestalts. These marks will be formed into structures of flatness that will communicate ‘things’ and ideas, allowing the viewer—an unwitting victim or willing participant—access into this portal of visual space. Essentially, this act of image making is an amalgamation of subsequent abstracted marks added upon and into reliable sequences, creating recognisable or pleasantly suggestive combinations and co-ordinations of skill, delighting and informing the viewer, and conversely, also seducing them. Often, that power resides in only the briefest of gestural movements; a few lines can literally change a viewer’s perspective, triggering an avalanche of personal memories which up to that moment were dormant, recessed and possibly secreted away. A picture can indeed speak a thousand words. I approach the beginning of each drawing solely with these premises in mind, because I acknowledge that the creative experience is also triggering my own consciousness, perhaps in similar fundamental directions to the viewers, who have come to look at what is illogical. Art is not perceived reality, yet it seems to identify and give form, suggesting the material and mental matrices of living.

There are conscious things that enter the drawing environment: a desk, lights, a chair, open windows for ventilation, or, recently, an air-conditioned cell in a house. I also usually set a timer for an hour and a half and begin by looking at areas of the surface of the drawing where my instinct rests—like the visiting bee. I frequently use the 0.5 pencil and a plastic stencil to give presence to a new set of previously unintended sequences, which are morphed as the marks are constructed. There is no preconceived form; I keep the unknowingness as paramount, and my sole intention is to articulate a stream of interlocking invention, like an organic weaving with the threads pulled out of my memory banks. It is not just that I do not have control, but that part of the decision-making process is suspended, willfully so, because it is and stems from my ego, always at play, wanting to structure meanings. When this happens, the drawing quickly grinds to an inevitable halt; absolute freedom has been surrendered. An analogy for this process and thinking is found in the observation of a child playing and creating; there is no preconceived story there, the creative process is triggered by an internal will, which becomes a way of learning as a sequential potential is activated.

This idea of an ego interfering in the drawing process reminds me of a conversation in yoga, which I had and was developing with an old man Yogi, who was operating as if under cover, living on a hillside ashram in Deigo Martin. An honest, ongoing discussion about life and living things, a dialogue which penetrated my waking existence. There were no classes, but continuous Satsang over some 16 years, sometimes brief, and others for a few hours. Yoga consecrates disciplines; it is a range of mental and physical skills, it is martial and ruthless, physical and mental. It is the deliberate practice of quietening the ego, as and if necessary. I recognised that the same process is reflected in my attitude in the studio, and in that awareness, the drawings become denser surfaces, allowing the weave of even more complexities. The restraint of the ego created a detachment from the surfaces themselves, an unmitigated sense of creative freedoms locked into the processes of drawing, the contradictions ever continuing, a magicking.

Since 1987, in somewhat direct and associative contrast, the art world and our other worlds started incorporating digital interfaces. We are now part cyborgs, utterly reliant upon our handheld devices—a virtual world which I felt I was already inhabiting, except I was and have been the content creator. Also, over those years, curatorial politics about the artists’ production, their orientations and predispositions to an increasing necessity for political correctness, are driving market trends and self-conscious textual and intellectual investigations; this work does not fit or even respect these new boundaries. In my immediate locality, I found myself alone with this developing mania, with social media being the avenue by which parts of this thinking are allowed to emerge and have presence. It is also easy to suggest ideas of ‘spirituality’, but that is slippery ground; the religious would want to claim it, and the scientists would want to be proving or disproving it—the intangible, the mysteries of what cannot be grasped. I found myself in a kind of intellectual no man’s land with this work; the yogi and I had spoken about this ‘black light’ notion as being the intangible source from where these thought sequences emerged. The work is removed from notions of relevance to society to illustrate, comment, fix or influence an audience, to explore that notion of holding the viewer’s attention in a silent wordless gazing, not wanting to please or inform, but to arrest an innocent passerby.

Nearly forty years later, in 2002, the work reached the 22nd Anniversary of the São Paolo Bienal, but a career moment had to take a back seat due to personal reasons; however, the work did not stop, it just went quiet. In the past, simply setting up an ‘office’ at different domestic locations was the priority, working with influences from perceived fields of my wider life, and within my own internal landscapes, as well as from my years here in Trinidad. My mind, I suppose like everyone else’s, is constantly processing all this stuff of existence, the living of ‘it’; in the studio, some of that processing is accelerated, some recessed to allow the creative equations to be in operation more specifically and skillfully. I feel as if these drawings are sustained moments when the fields of action are temporarily compressed and reduced to sequential patterning, weaving spells and conjurations.

*

Edward (Eddie) Bowen studied at Croydon College, UK, from 1981 to 1985. He has since been living and working in Trinidad, often letting his environment in San Souci be his muse.