The Captive Globe

This essay is about a drawing—or rather, about the insight embedded within that drawing and the life it has taken on in the forty-five years since it was made. The drawing in question is The City of the Captive Globe. It was created in 1972, first published in 1978 by Rem Koolhaas in Delirious New York, and co-credited to Zoe Zenghelis*, partner in the then newly formed Office for Metropolitan Architecture. The City of the Captive Globe illustrates in large part the thesis of a later book, which identifies Manhattan as the mythical laboratory for the invention of a new revolutionary lifestyle: the ‘culture of congestion,’ simultaneously informed by an explosion of human density and an invasion of new technologies.[1]

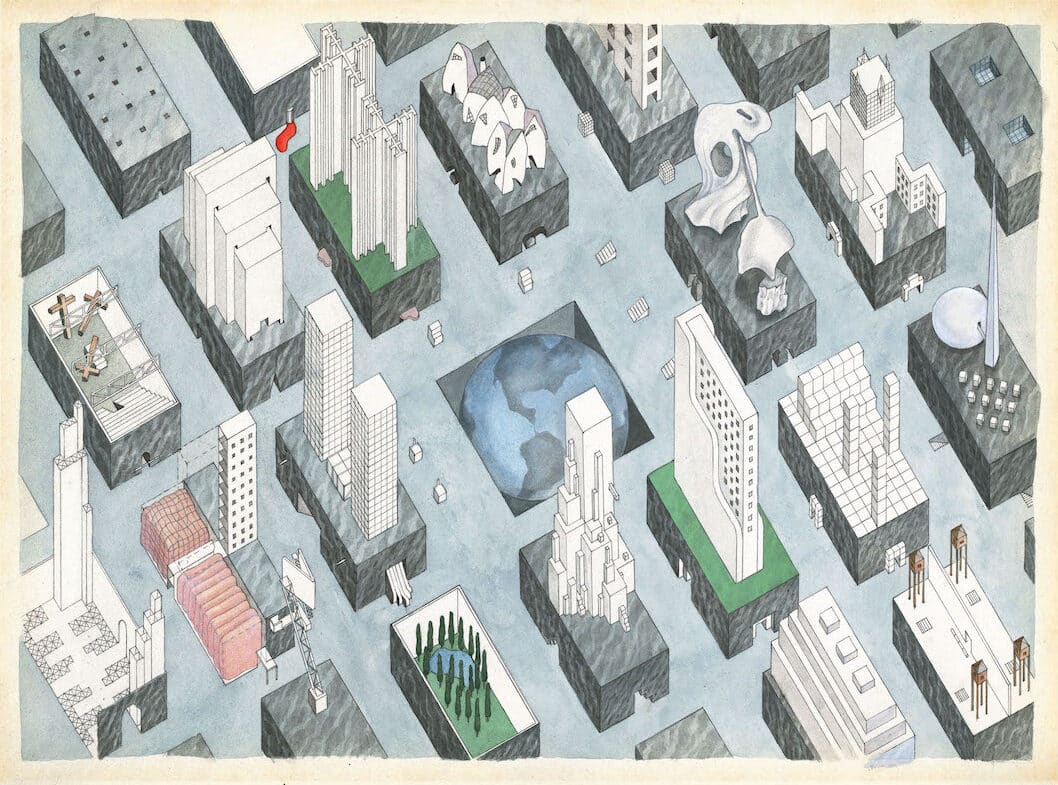

The drawing shows a roughly twenty-block fragment of a theoretically infinite grid. The proportions of the individual blocks suggest that it is the Manhattan grid, but because it lacks identifiable landmarks one cannot be quite sure. To the extent that the drawing owes its origin to Manhattan, its debt is to the idea of Manhattan rather than the physical place. In the absence of a specified location, the grid becomes an autonomous ideological statement.

In The City of the Captive Globe, ‘each Science or Mania has its own plot. On each plot stands an identical base, built from heavy polished stone. To facilitate and provoke speculative activity, these bases— ideological laboratories—suspend unwelcome laws, undeniable truths, to create nonexistent physical conditions. From these solid blocks of granite, each philosophy has the right to expand infinitely toward heaven.’[2] The City of the Captive Globe indiscriminately absorbs architectures that were previously thought incompatible. In it we glimpse El Lissitzky’s Lenin’s Stand, Dalí’s Architectonic Angelus of Millet, Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin, Malevich’s Architecton, Raymond Hood’s RCA Building, and Wallace Harrison’s Trylon and Perisphere for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. ‘All these Institutes together form an enormous incubator of the World itself; they are breeding on the Globe. Through our feverish thinking in the Towers, the Globe gains weight. Its temperature rises slowly. In spite of the most humiliating setbacks, its ageless pregnancy survives.’[3]

The language is celebratory, but the message remains ambiguous. Are we looking at an endorsement, a warning, or simply an observation? When pregnancy is ageless, birth is infinitely postponed. Potential takes the place of deliverance. Progress becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The question of what one is progressing toward must forever remain unanswered.

‘The City of the Captive Globe is devoted to the artificial conception and accelerated birth of theories, interpretations, mental constructions, proposals and their infliction on the World. It is the capital of Ego, where science, art, poetry and forms of madness compete under ideal conditions to invent, destroy and restore the world of phenomenal Reality. Each science or mania has its own plot.’[4] The ‘capital of Ego’ no longer supports architecture in any absolute sense. In exchange for that withdrawal, however, it gives back to architecture its status of perpetual experimentation. It replaces a commitment to architectural modernism with one to modernity, for it is the experiment that is the essence of modernity, not modern architecture’s overblown pretence of any definitive answer. The architectures featured in the drawing are pursuits; their value lies in their endeavour, not in their finite states. The experiment can be conducted only when its sole and nonnegotiable condition is met: the permanent suspension of all judgment.

The drawing is ostensibly about architecture, but it is also a comment on architecture’s relative importance. Former visionary utopias, embodied in singular tower blocks, are lined up like products in a department store. The drawing makes a pointed statement about the futility of architecture’s larger pretensions; it mocks architecture’s aspirations to control. The ideology of the grid spells the end of architecture as a totalizing discipline. After The City of the Captive Globe, architecture exists only in the plural, suggesting an apex of multiple choice. Formerly absolute ideologies are confined to the walls of their facades; their validity is limited to the boundary of their plots. Their simple coexistence within a single territory makes them relative; each vision cancels out the validity of the next. In The City of the Captive Globe architecture has agreed to disagree.

Although the drawing has a distinctly postmodern flavour, it signals the end of postmodernism as the prevailing style. Like any other style, postmodernism is just one of many. At the same time, The City of the Captive Globe makes a convincing case that modernity itself is now postmodern—a trope to be worn lightly, like the rest. The drawing announces a distinctly agnostic phase in architecture, a form of architectural nihilism, intended to cleanse the discipline of its false projections and delusional tendencies. The grid is intentionally blind to the architectures that inhabit it. They are interchangeable ingredients within a larger order that exists with or without them. In The City of the Captive Globe the accumulated masterpieces within the grid do little to disguise the fact that the real masterpiece is the grid itself. The grid precedes the individual architectures and will outlive them all.

At the time of its publication in 1978, the drawing sparked controversy. The implied rejection of architecture’s potential to embody absolute truths, or even to express any meaning at all, was considered to be a cynical and philistine proposition. It is unclear to what extent The City of the Captive Globe was ever intended to serve as a model. If it was, time has overtaken it. Nearly half a century later, the metropolis, for which New York served as the case study, is no longer an exclusively Western concept. As the challenge of incorporating the idiosyncrasies of an ever-expanding spectrum of diversity becomes central, it is no longer a culture of congestion but rather a congestion of cultures that is the leading paradigm. The metropolis of the twenty-first century is in every sense more radical than the drawing, the message of which is now an understatement. As often happens, reality defies and surpasses all expectations.

Where the original drawing gathered a collection of carefully curated examples, all different, but all architecture, the more recent incarnation of the metropolis pushes the idea of what can exist together further still. Ultimately this metropolis negates the difference between architecture and nonarchitecture, reserving judgment not only on its varied manifestations but also on the necessity of architecture altogether. It is the essence of the modern metropolis that both everything and nothing qualify as architecture. Anything may become architecture. That is its most profound conclusion. Conversely, anything considered architecture can stop being so, at which point architecture is liberated to become history; it can retire.

It can be concluded that the Office for Metropolitan Architecture emerged from the annihilation of its subject. As soon as architecture becomes ‘metropolitan,’ it is no longer architecture—at least not architecture as it lived in the minds of architects until that moment. From there on, architecture exists in the knowledge of its own relativity. Metropolitan architecture is like religion after Einstein.

That is not to say that architecture is no longer practiced. The effect of the destruction of any possible shared truth seems only to have been a general increase in architecture’s productivity; the past four decades have produced an architectural big bang. Thus, the drawing can be read as modern architecture’s graveyard, as well as the site of its rebirth. As the death of God produced an infinite proliferation of deities, ‘metropolitan architecture’ has legitimized (and promoted) an infinite proliferation of architectures. It has relieved later generations of excess baggage and enabled a new breed of modern architectures to arise, produced in the knowledge that architecture no longer matters in the same way.

The implications of the drawing are not limited to architecture. Nor is the metropolis a testament only to architecture’s limited relevance; like the infinite grid, its mockery extends to all attempts to create order on a larger scale. After architecture, urbanism is equally unable to establish any semblance of ideological consensus. If the twentieth-century metropolis was the bond between the skyscraper and the grid, the metropolis of the twenty-first emerges from its dissolution. The Manhattan grid is no longer an absolute, one-size-fits-all solution but merely one of many ways to organize the coexistence of individual fragments. There is a choice among square grids and radial grids, morphed grids and organic grids, impossible grids and, with increasing frequency, no grid at all. The metropolis of the twenty-first century is like a theme park. Formerly totalizing principles reappear in a buffet of orchestrated experiences; memories of particular cities make their encores as products of choice. Composition gives way to impression, cohesion to fragmentation, urban planning to Photoshop.

Does the modern metropolis express the essence of modernity, or does it signal its complete undoing? Does it announce not the triumph of a single style or system but simply the legitimacy of agreeing to disagree, of pushing any finite system to its limits? Whenever coherence proves untenable within the confines of a certain discipline, we simply move on to the next discipline, and an endless process of deferral is set in motion: architecture gives way to urbanism, urbanism gives way to planning, and planning gives way to politics. The professional authority of each domain is valid only as long as it is able to contain the disarray created by the previous one. Modernity becomes about accommodating dissent, and acquiring incremental degrees of abstraction. Modernity’s final and unexpected plot twist is the revelation that the highest degree of abstraction and the lowest common denominator are one and the same. Only in abstraction is the lowest common denominator tolerable, exposing matters of ‘taste’ for what they really are: a form of folklore.

In pursuit of greater and greater abstraction, modernity turns art, religion, culture, and architecture into successive terrains of scorched earth. They become ‘free’ expressions, irrelevant to our historical destiny. Still, this freedom exists only because they are subcategories which are light, easy to digest, and even easier to dismiss. Casual bloggers are search-engine-result neighbours alongside major intellectual authorities (insofar as the latter can be said to exist). Obscure political parties acquire major parliamentary followings overnight, only to disappear in the next election cycle. Diversity signifies irrelevance more than it does freedom. Perhaps this explains the sense of impoverishment we experience as we watch modernization unfold: the sense of trading in previous certainties for unknown multiplicities. In religion, this is the promise of the ever after; in modernity, it is the promise of a future that may never come.

The only remaining absolute resides in the collective embrace of economic values. Even the political sphere has become a subsector of the economy. In the late twentieth century political theorist Francis Fukuyama attempted to make a case for the universal embrace of economic values as the triumph of Western liberal democracy. Authoritarian regimes that perform every bit as well as democracies, if not better, have definitively rebuked this theory. The current world consumes the political and its doctrines à la carte. China does so literally: one country, two systems. Western liberal democracy is perceived now as just one of multiple political options, with more need than ever to argue its universal claims. The political—like art, religion, culture, and architecture before it—is professed in the knowledge that it no longer matters, at least not in the same way.

It is the global economy, subject to absolutely nobody’s control, that defines us as a collective. Modernity’s evolution toward abstraction ultimately divorces it from the exercise of political will; our apparent consensus defies our collective judgment. Disorientation ensues. We talk about freedom passionately yet we do so without describing freedom from what; we talk about progress without stating what we are progressing toward. The appearance of freedom becomes inversely proportional to real freedom, which is ultimately the ability to control our own destiny. Modernity now finds itself at odds with democracy. The economy tout court becomes the sole remaining source of cohesion in the modern world, the only real form of objectivity, and the only central organizing principle.

In identifying the economy as its endgame, the evolution of modernity runs into trouble. Understanding the economy used to be about discerning the control of the means of production, a notion that implies an end that lies outside the economy. Money is surely to be converted into a value other than itself, the measure of which is the elevation of man’s existence. Insofar as art, culture, and perhaps even architecture may constitute such a value, they are what constitute richness. Where the economy is the means, they are the end. But in the absence of either intrinsic or shared value, only exchange value determines worth. The cycle of exchange of which they become part ultimately leads to a conceptual reversal where the end becomes the means, and the means become the end. Art has become a high-risk asset class, generating both stratospheric returns and catastrophic losses. Architecture in the form of real estate creates booms and busts alike and played its part in bringing the world to the brink of the financial abyss in 2008. Ironically, having been shorn of their ideological values, art and architecture have become more dangerous than ever.

Approaching five decades since its publication, The City of the Captive Globe presents a form of dystopian foresight extending well beyond the professional realms of architecture. What the grid was to the various buildings, the economy has become to art, culture, religion, and politics. Yet the apparent ability of architecture to disrupt the economy also allows a new interpretation of the drawing with an unrecognized potential. The individual architectures depicted in it are not mere expressions of their own simple instability; collectively they embody the complex instability of the system as a whole. Metropolitan architecture becomes the sum total of architectures, whose combined weight could topple the stock market. The power of the multifarious towers lies not in the individual ideologies represented by each but in the collective capacity to derail an otherwise authorless consensus. Thus the drawing’s second message becomes a rejection of its first: architecture’s apparent descent into chaotic volatility becomes the source of its revenge—a way to reclaim the globe from captivity.

Notes

- Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1994).

- Ibid, 294.

- Ibid, 294.

- Ibid, 294.

* Editors’ note: there are several versions of The City of the Captive Globe drawing some of which are credited to Rem Koolhaas and Zoe Zenghelis (see the version in the FRAC collection) and others to Koolhaas and Madelon Vriesendorp, including the version illustrating this text, from MoMA.

Excerpted, with the author’s and publisher’s permission, from Reinier de Graaf, Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 459–65.

– Richard Hall