The Craft of Carpentry: Drawing Life from Japan’s Forests

The Craft of Carpentry exhibition at Japan House London is striking for showing an ongoing craft tradition and architectural culture that appears to be both attuned to history and inherently adaptable.

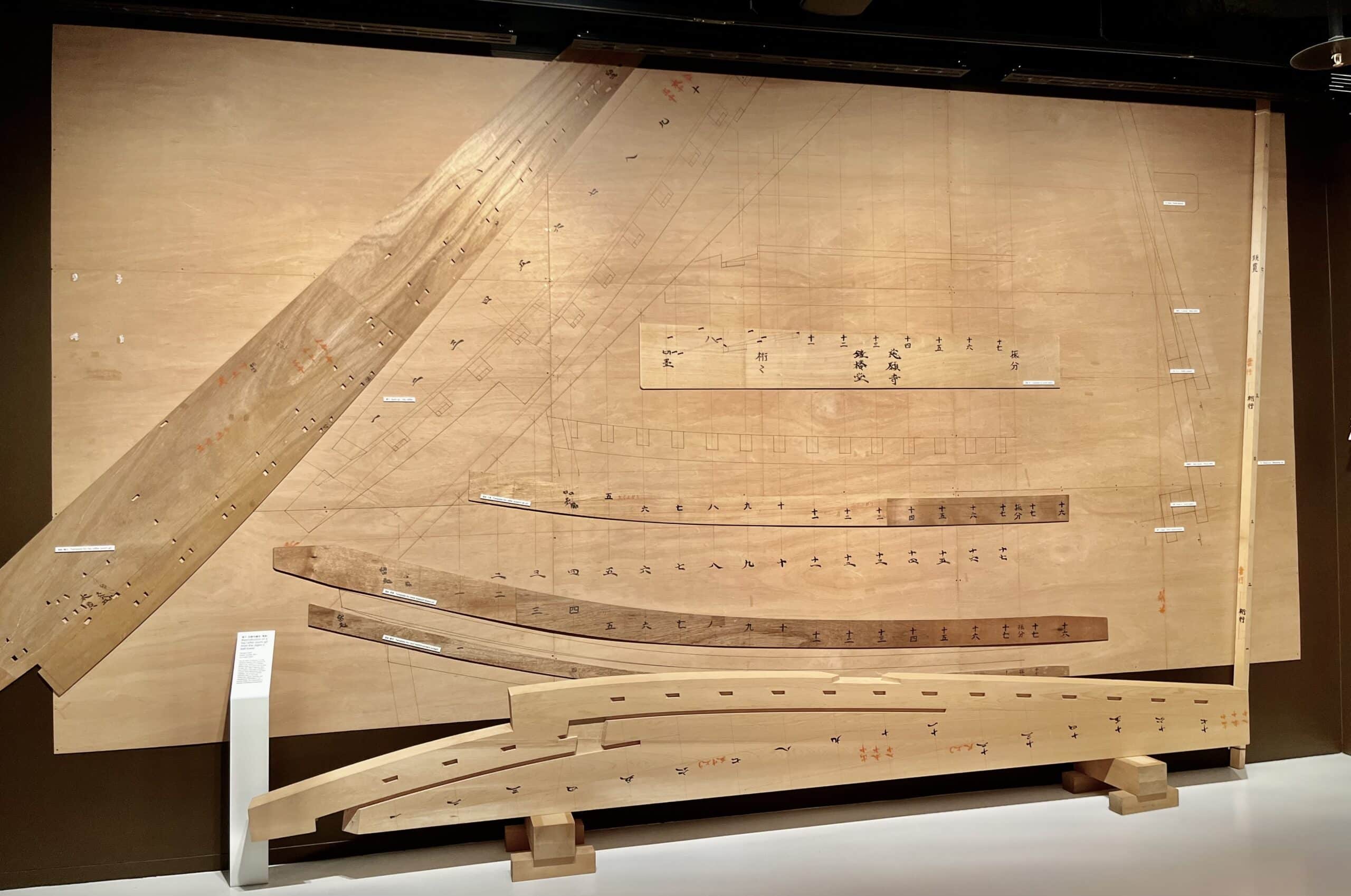

A fellow visitor to the exhibition told me about his father who had been a sukiya carpenter, building their family home in the traditional manner, among other projects. He explained how these craftsmen would act as draughtsman, engineer and carpenter on a given project; the kind of deep knowledge they applied was a tacit, practice-based, material understanding, in contrast to more abstract academic knowledge. Indeed, the craftsmen’s drawings displayed in the exhibition demonstrate the material confidence or fluency of their maker, as well as suggesting a deep capacity for original work. The most dramatic of these is a working drawing of a hip rafter, drawn directly onto sheets of plywood at full scale. The caption explains that it was made in 2010, for the renovation of a building at the Jigen–ji temple, and that this practice of 1:1 drawing on site is typically used to work through especially complicated pieces of joinery.

The periodic rebuilding and restoration of these sacred buildings is an expected and culturally important part of their life, and it is by making drawings like this that contemporary carpenters can decipher the work of their forebears and decide how best to respond.

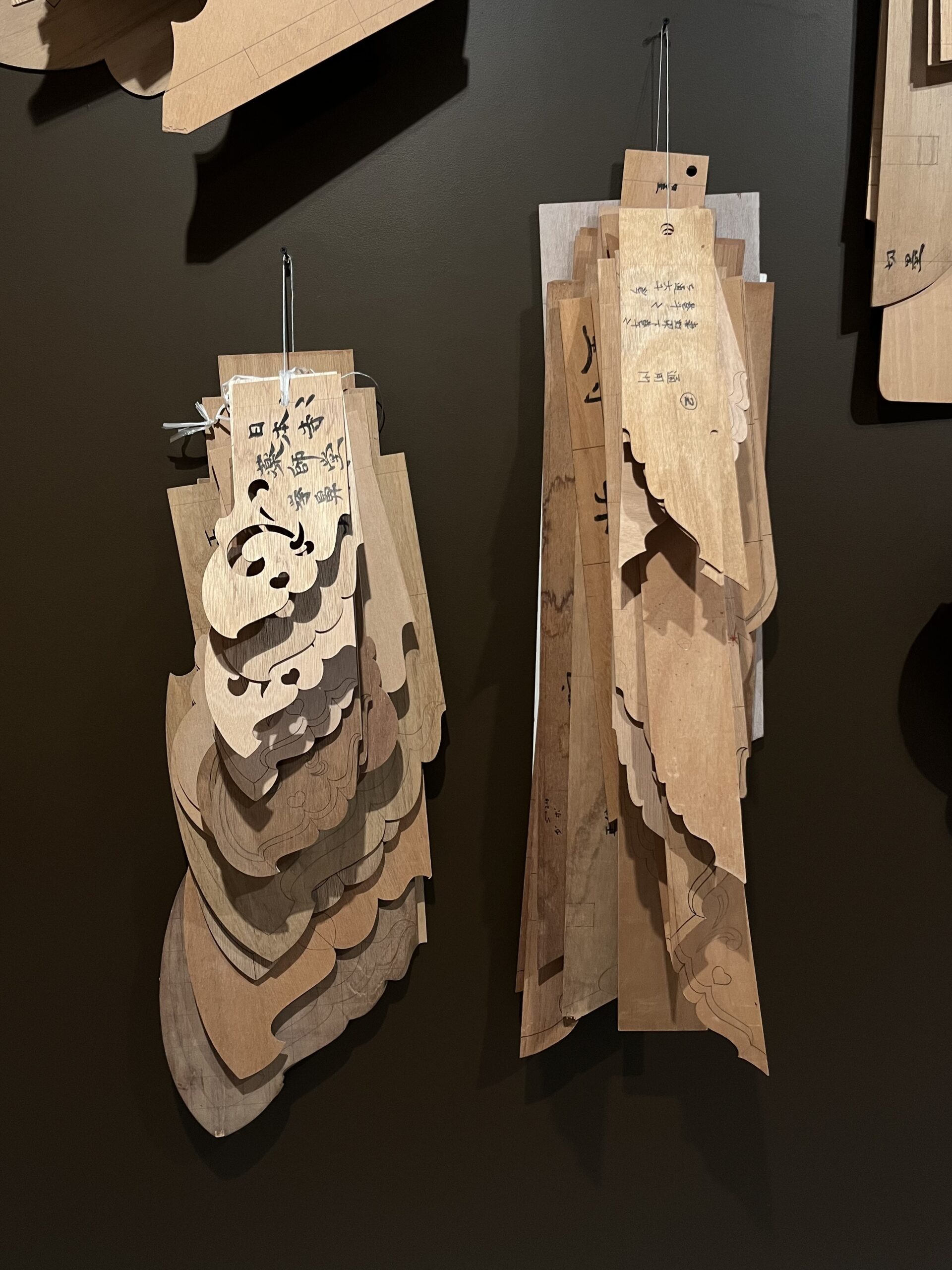

The display also includes a large number of ply templates, used for testing and tracing the complex profiles required for such buildings. This too is a way of working that involves conformity to the traditional language, but also suggests a freedom to adapt details to suit new cases.

It is tempting to see in this identity of draughtsman and builder, and the practice of resolving design on site at full scale, a potential for original creative work that is relatively lacking in contemporary building practices where a divorce between ‘head and hand’ is built into the process, and a library of standardised component systems resists original organisation. By contrast, these drawings and templates suggest an opportunity for the craftsman to mediate on a case-by-case basis between the ‘rails’ of tradition on the one hand, and the specificities of natural materials, site, and project on the other.

As well as these drawings and templates, the exhibits include a display of wood-working tools, grouped according to their general purpose: marking and measuring, sawing, planing, chiselling, hammering, chopping, and maintenance. Going by a 1943 survey of Tokyo carpenters, these 80 or so tools might represent only half those required by a single craftsman to work on a larger project at that time.[1]

The centrepieces of the exhibition are two scale recreations of Japanese buildings: a half-scale model of the column to roof detail of the Tōindō hall (1185–1333), part of the Yakushi–ji temple complex, and a full-scale structural model of the Sa–an teahouse (1742). Both buildings are shown pared-back, skeletal, alongside informative diagrams and animations of their constructional details. Whilst the exhibition thereby presents the tradition foremost through the lens of technique, what is palpable is the rich metaphoric content of the architecture, and its responsiveness to the cultural traditions of which the building forms a part.

A traditional Buddhist temple building, like the one shown at Japan House, was based on an ideal Chinese precedent in which a single roof extends to cover both a central room with a statue of the deity and a colonnaded space in front.[2] This creates deep eaves, which in turn help to achieve an appropriately shadowed, contemplative atmosphere in the depth of the plan. The model at the Japan House demonstrates how this important ritual aspect of the temple is achieved through the kumimono, an intricate system of blocks and brackets, which corbel outward from each post to support the cantilever of the roof. It is tempting to draw a comparison between this tectonic drama and that of a Corinthian capital; certainly, it is true that the structural device took on symbolic importance in its own right, continuing to be an essential decorative element in public buildings even after other structural solutions were found for the cantilevered roof.

The teahouse is carefully planned to facilitate the particular rituals of the chanoyu tea gathering. A stone hearth for preparing tea, and a central post, the naka–bashira, demarcates the guests’ seating area, kyaku–za, from the host’s area, temae–za. The equality of host and guests within the teahouse is established as the guests enter by bowing their heads and crouching under the nijiri–guchi, a low hatch-like door. Meanwhile, the host makes use of full-height doors to best attend to their guests.

The traditional aesthetic for this kind of teahouse is one of lightness and ‘naturalness’ that creates an atmosphere of tranquillity removed from everyday social status and responsibility. This is done, for example, using smaller diameter, minimally processed round logs for post and beam, and correspondingly thin walls between them. Of course, to achieve this impression of simplicity is no simple matter; it requires complex joinery techniques to invisibly join one curved surface to another, and specially prepared components to achieve such thin wall build-ups.

The lasting impression is of an architecture deeply enmeshed both in the forms of life of its occupants, and in the wider material, technological culture of its time and place. The specialised toolbox of the carpenter finds its correlate in the well-established architectonic language of each typology, and then again in the specific cultural habits performed therein. The longevity of this building tradition must be thanks in part to the expert carpenter’s capacity to resolve issues of design and propose original solutions, in response to the specificity of each situation.

Notes

- Nishiyama Marcello, ‘Understanding the variety of Japanese carpentry tools’, Japan House London, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/12/arts/design/superstudio-civa.html [accessed 03 May 2024].

- Tomoya Masuda, Living Architecture: Japanese (London: MacDonald & Co., 1971), 125.

Alfred Mowse is an architectural student based in London. He previously graduated from The Queen’s College, Oxford, where he studied philosophy and politics before recognising architecture as a way to approach these matters through purposive and collaborative practice. He has since gained practical experience working for Lynch Architects and Maccreannor Lavington.