The Ingredients of the Pudding: Alison and Peter Smithson’s Christmas Cards

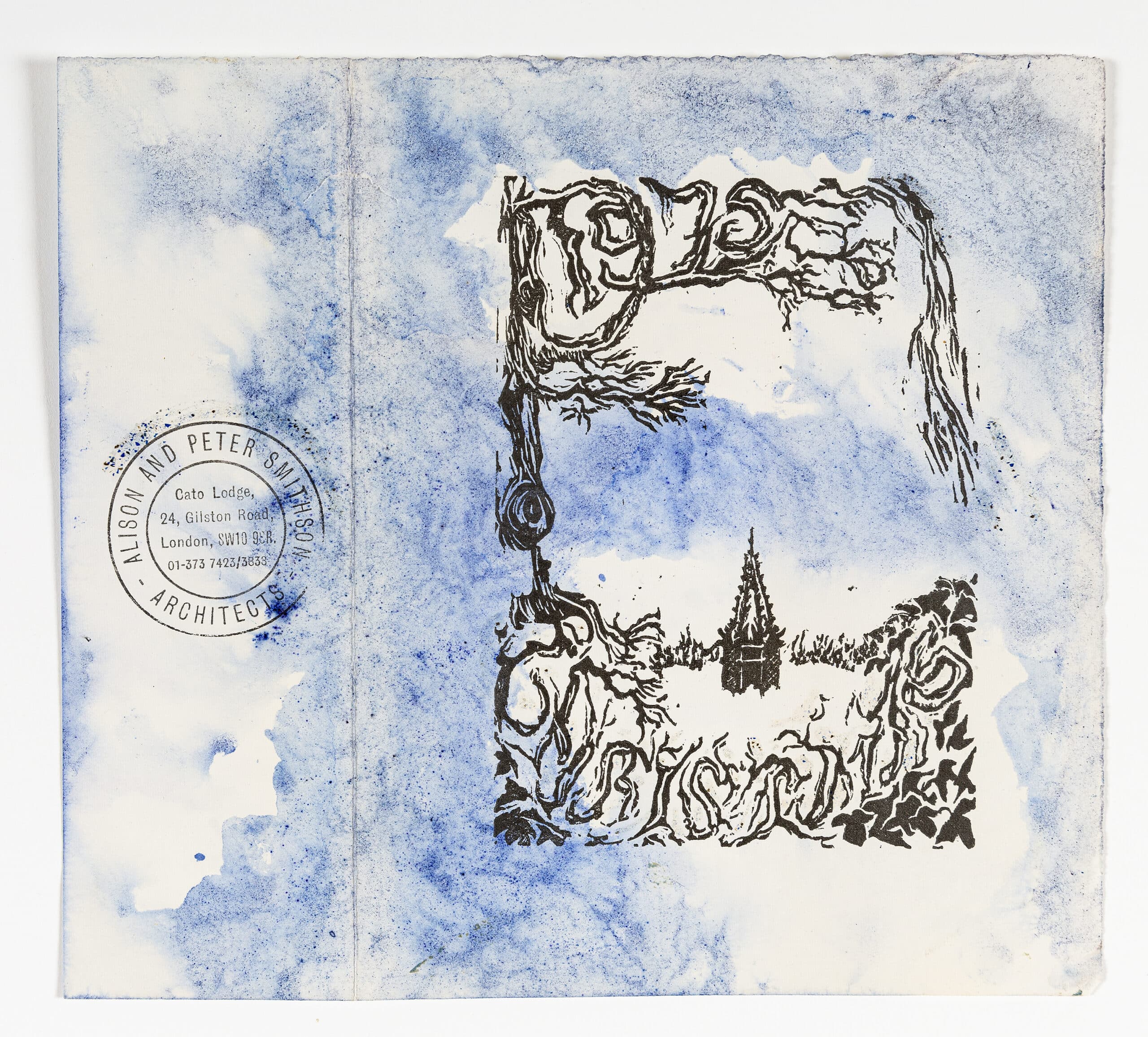

Drawing Matter is pleased to publish the following text to mark the opening of ‘Come Deck the Halls!’, an exhibition celebrating the work of Alison and Peter Smithson at Roca London Gallery (5 December 2025 – 31 January 2026). The exhibition provides an insight into their architectural thinking through the lens of Alison Smithson’s Christmas cards, spanning 1956 to 1992. An accompanying publication, The Christmas Card Catalogue: 1956–1992, from which this text is excerpted, will be available during the exhibition and online from www.shopsmithson.co.uk.

There is also revealed the play between the ‘ephemeral’ and the ‘permanent’. In our work the ephemeral and the permanent intertwine. The ephemeral being works on paper… Christmas cards in miniature space, invitation cards, posters, photographs, books in which ideas are tried out; performing the same role in the small as exhibitions at real scale… in transient material in advance of permanent construction.[1]

Alison and Peter Smithson did not have many opportunities to realise their design as buildings but during the fallow periods of their career they channelled all their creative energy into ephemeral projects, such as books, articles, conferences, manifestos, photographs, exhibitions, Christmas cards, and so on. In 1995, Peter encouraged his readers to pay attention to these small, fleeting architectures that had enabled them to put their ideas into practice and try out their theories with far greater freedom than a building might allow. Researching other new architectures also formed part of their on-going reflection: ‘every work is a new assessment, a new response to what is already there’.[2]

This play between the ephemeral and the permanent is particularly obvious in The Shift, the Smithsons’ first published compilation of their own work, and the first time they openly showcased their professional interest in the ephemera so closely interwoven with their family life.[3] The Christmas cards appearing in the pages of The Shift create a narrative of their work as an intertwined flux of ideas and creations. Moving to and fro in circular time, the book is a remaking that offers new insights and connections with deeper levels of meaning, sharing lessons re-learned, experiences re-lived and ideas that are rekindled and chewed over again. Within it, action is always guided by thought.

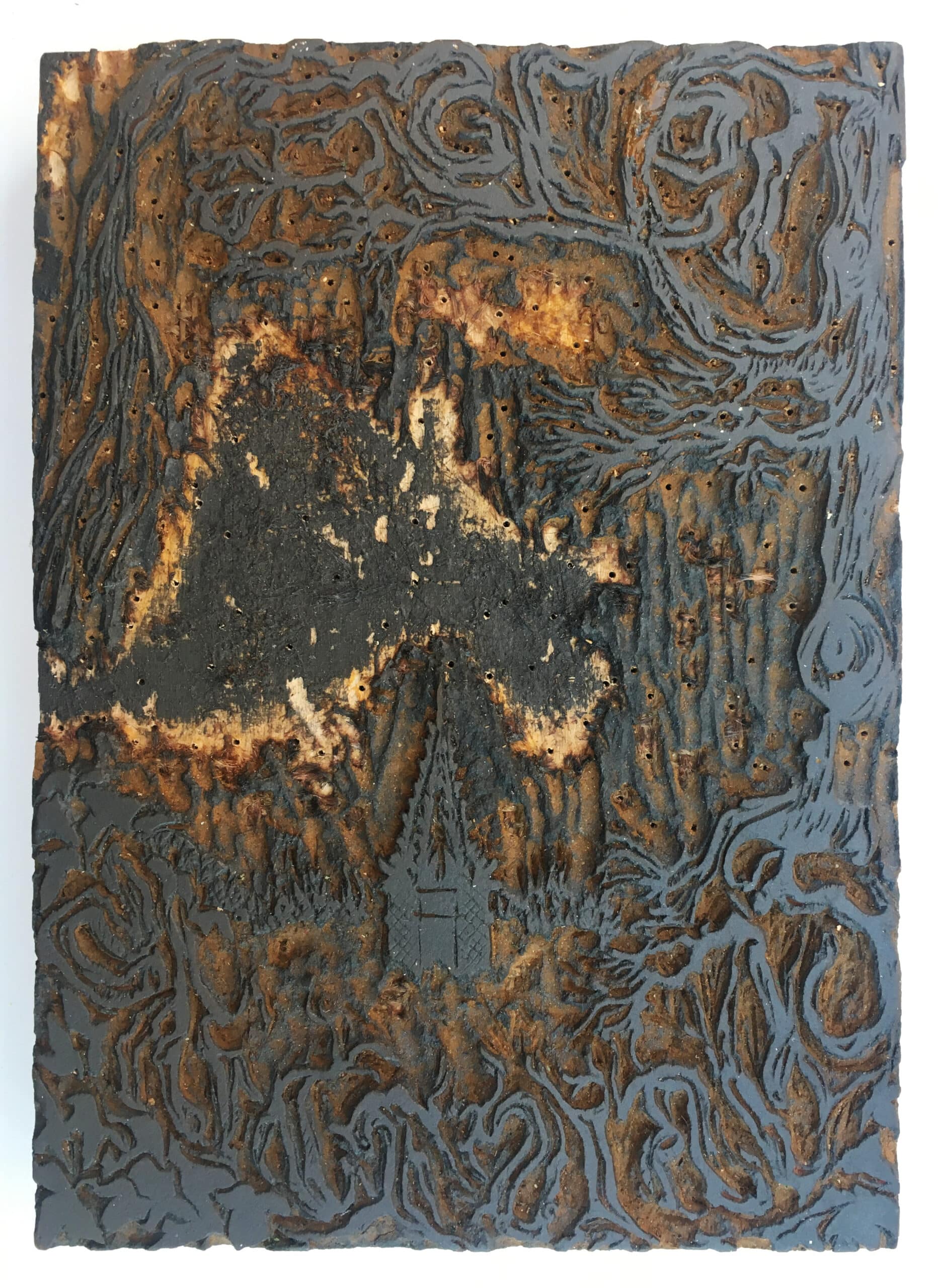

Although the Smithsons began making and sending their own Christmas cards in 1949, it was not until 1956 that they became ‘mood carriers’, vehicles for their ideas and work. From then on, you can trace many threads in the couple’s work through the cards: the constant presence of nature in their reflections, diverse artistic influences in their graphics, and the importance of materiality, including Alison’s hand in the Christmas cards.

Using tissue paper they bought at a newsagents on High Holborn, some way from their house on Limerston Street, they began with simple experiments, such as the 1956 card with its multi-coloured strip or pennon, the 1957 card entitled ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’, the antler-themed card of 1959, and the Christmas bauble abstract that Alison created for the card of 1960.

These cards were all handmade paper cut-outs, whose tactile connotations were also present, in one way or another, in all subsequent cards. Each year, this sensory quality forged a personal, tangible link between their work and those receiving the cards. Juhani Pallasmaa describes the subtle connection conveyed by hand-made items magnificently when he explains:

As I am looking at a Suprematist painting by Kasimir Malevich, I do not see it as a geometric gestalt but as an icon meticulously painted by the artist’s hand. The surface of cracked paint conveys a sense of materiality, work and time, and I find myself thinking of the inspired hand of the painter holding a brush.[4]

Likewise, Alison was to be found devoting her thoughts, hands, and time with the utmost sensitivity to condensing their work and sharing it each year, in the hope that those receiving the cards could become party to their reflective process. Each Christmas card was intended to keep alive links with their loved ones, but also between their projects.

These paper cut-outs dating from the 1950s provided the Smithsons with a simple medium in which to realise or fine-tune their ideas. The outcome was a new family of shapes that they tried out in drawings, diagrams, and Christmas cards in the following decade. They specifically mention the influence that such experiments had on the cards of 1963, 1965, 1966 and 1967.[5]

From the beginning of their career in the 1950s, the Smithsons developed a broad spectrum of graphic language to convey their thoughts. This was thanks in part to their links with artistic circles in London at that time, particularly the other members of the Independent Group. The ‘as found’ aesthetic, a recurring theme in their work, was first employed after they met Nigel Henderson and saw in his photographs the perceptive acknowledgement of real life around his house in Bethnal Green:

Thus the ‘as found’ was a new seeing of the ordinary, an openness as to how prosaic ‘things’ could re-energise our [the Smithsons’] inventive activity, and enabled new life to be breathed into any items to hand, where the art is in the picking up, turning over and putting-with.[6]

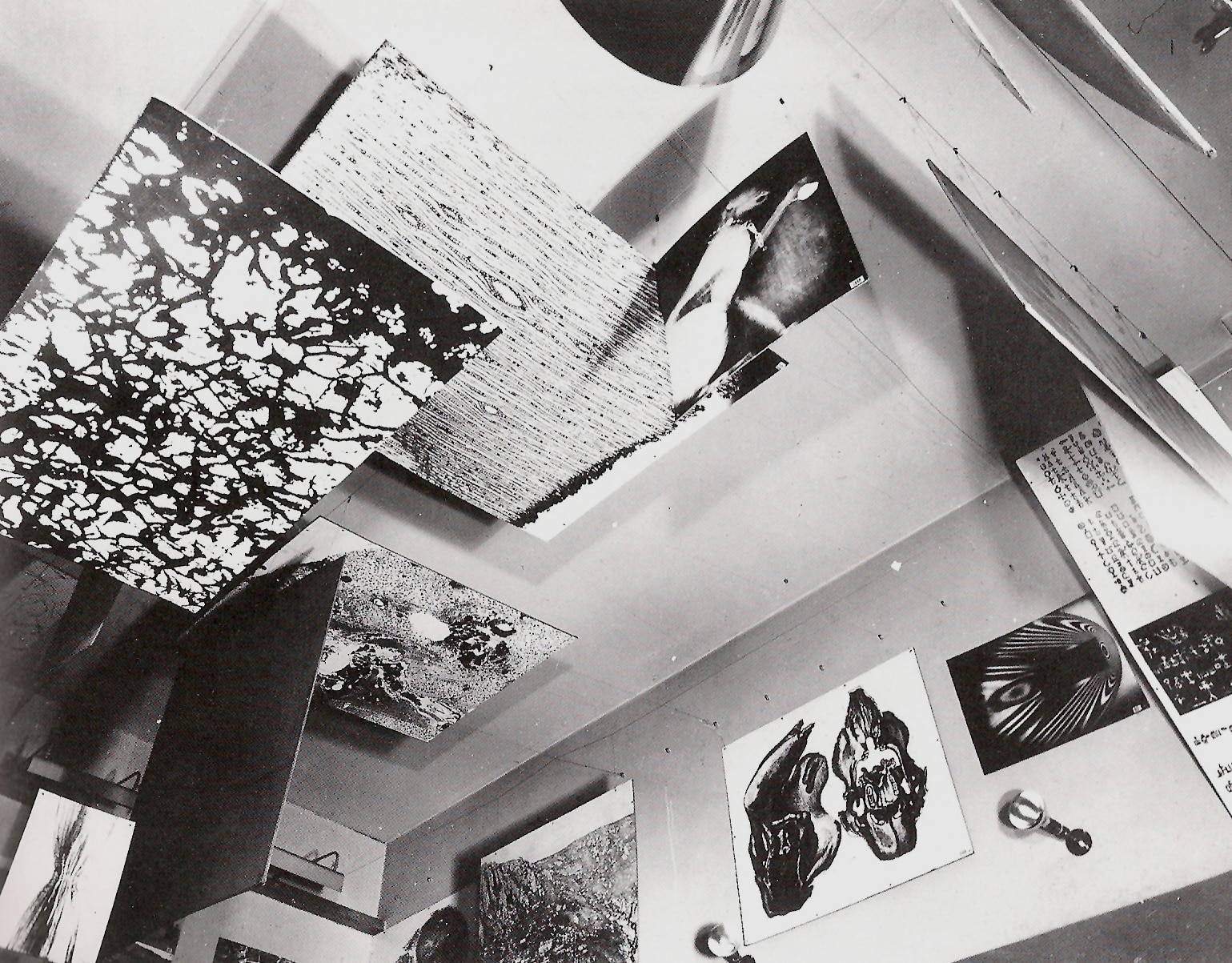

They continued to work in this way on certain Christmas cards decades later in the 1970s.[7] The 1976 card is a re-make of a 1953 collage based on popular ‘as found’ Christmas cards of the 1950s. This collage also appeared on the cover of two texts ‘The Christmas Tree’ (1976) and ‘Calendar of Christmas’ (1976). Aside from its successive re-makes, what makes this card so interesting is its use of the language of overlapping ‘as found’ images that had been tried out decades earlier in the Parallel of Life and Art (1953) and Wedding in the City (1968) exhibitions, had inspired the Lucas Headquarters proposal (1973/4),[8] and are crucial for understanding the overlapping reflections many years later in the ‘TischleinDeckDich a.s.o.’ exhibition (1993).[9]

The Smithsons’ strolls around London’s East End, observing street life with their friend, the photographer Nigel Henderson, triggered the ‘as found’ aesthetic and their concept of ‘signs of occupancy’. Similarly, a close friendship with sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi inevitably affected how they worked with scrapbooks, collage and images. As they say in the book Urban Structuring:

It was necessary in the early ’50s to look to the works of painter Pollock and sculptor Paolozzi for a complete image system, for an order with a structure and a certain tension, where every piece was correspondingly new in a new system of relationship.[10]

Alongside Paolozzi and Jackon Pollock, Paul Klee also deserves a mention for his impact on what the Smithsons called the ‘graphics of movement’:

Intellectually indicative graphics might be said to have been invented by Klee: not as a notation of people and vehicle movement, useful to urbanists, but a teaching graphic to convey the ability of shapes to work together to put over a message that a new ordering was possible: moreover, that this new ordering had been invented.[11]

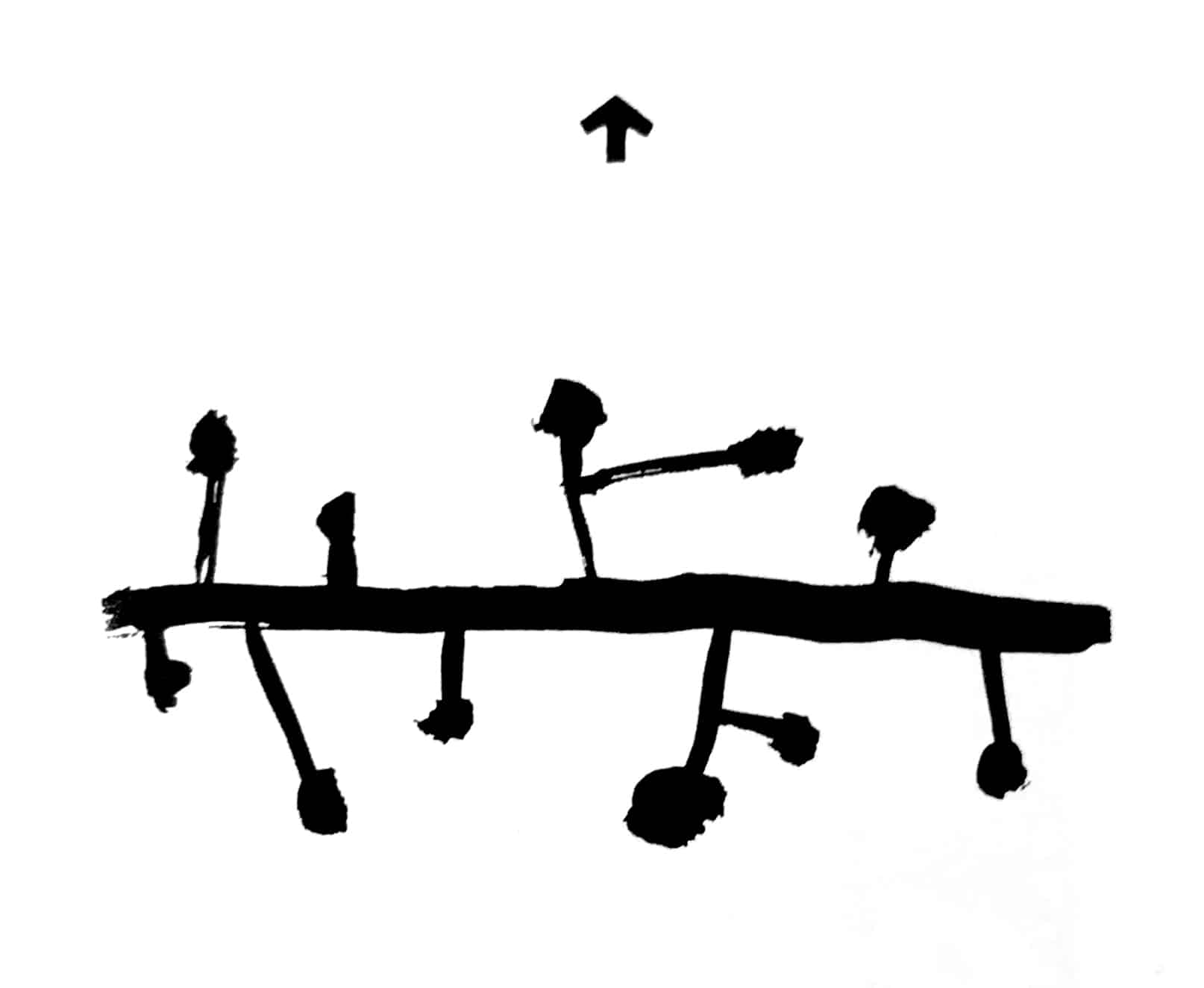

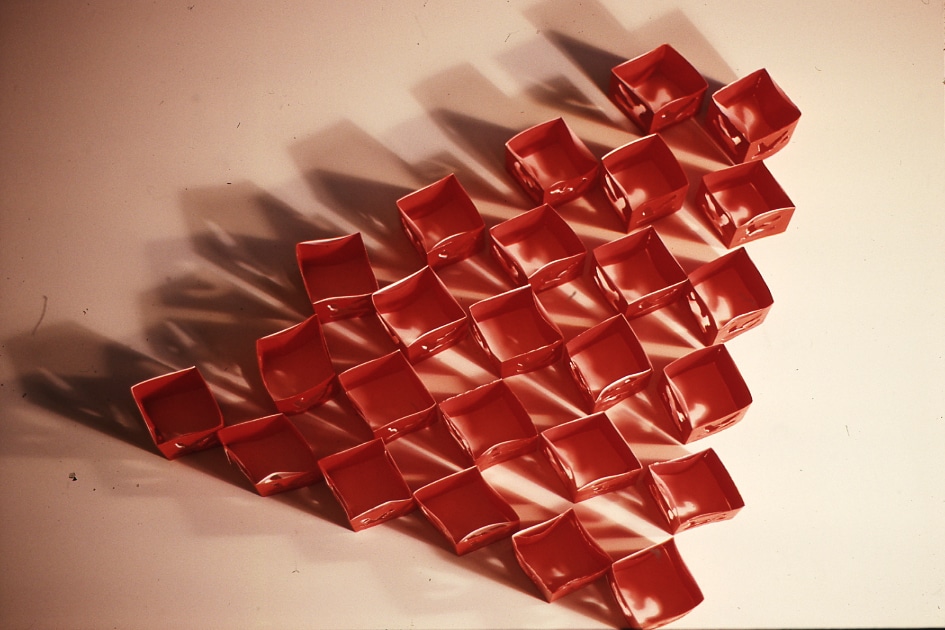

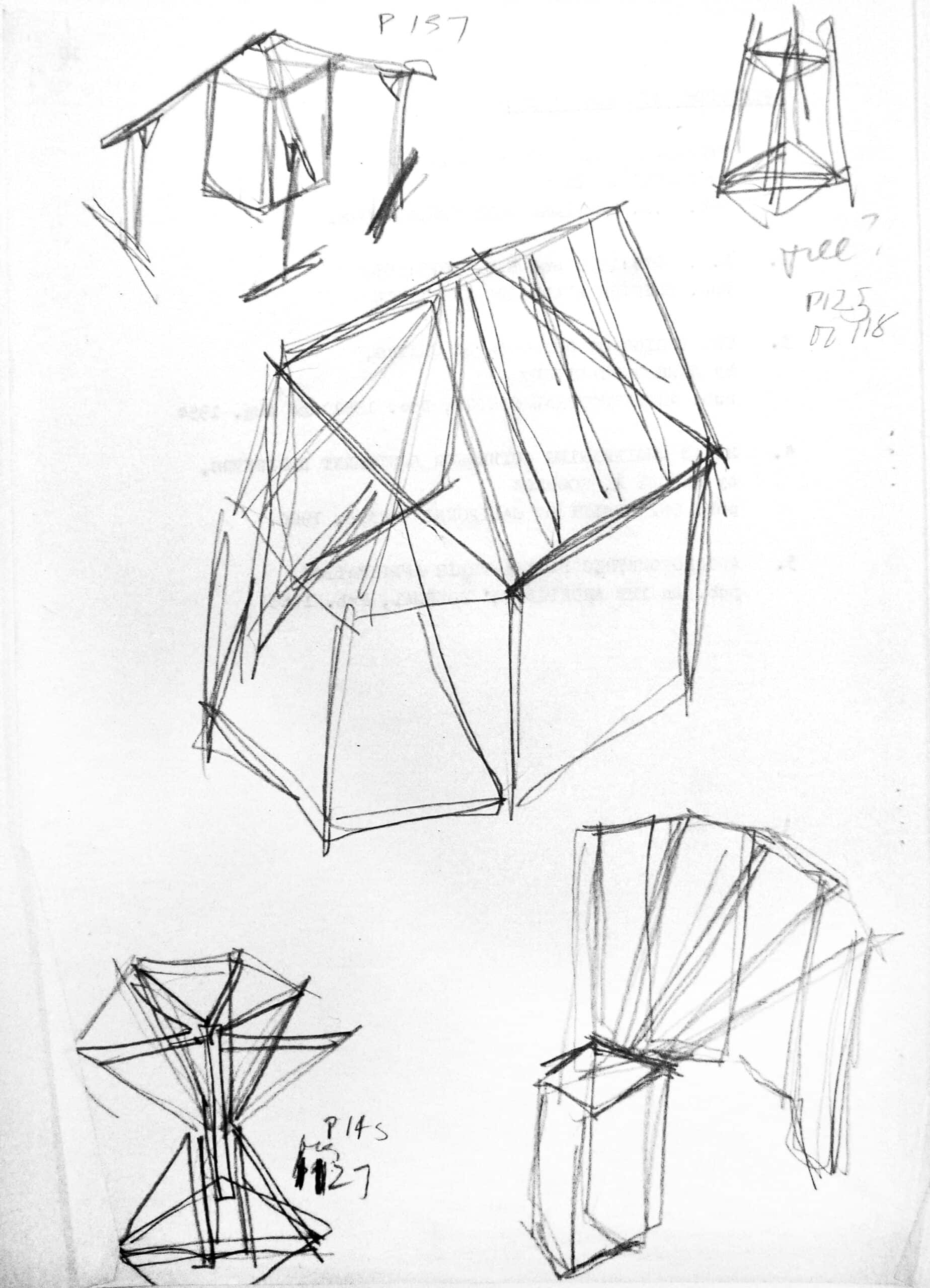

The development of all this graphic language from the 1950s and throughout their career is clear to see in the Christmas cards which, by transforming graphics

into small devices or objects that could be handled, incorporated another more physical dimension, and became sculptural as much as they were graphical.[12]

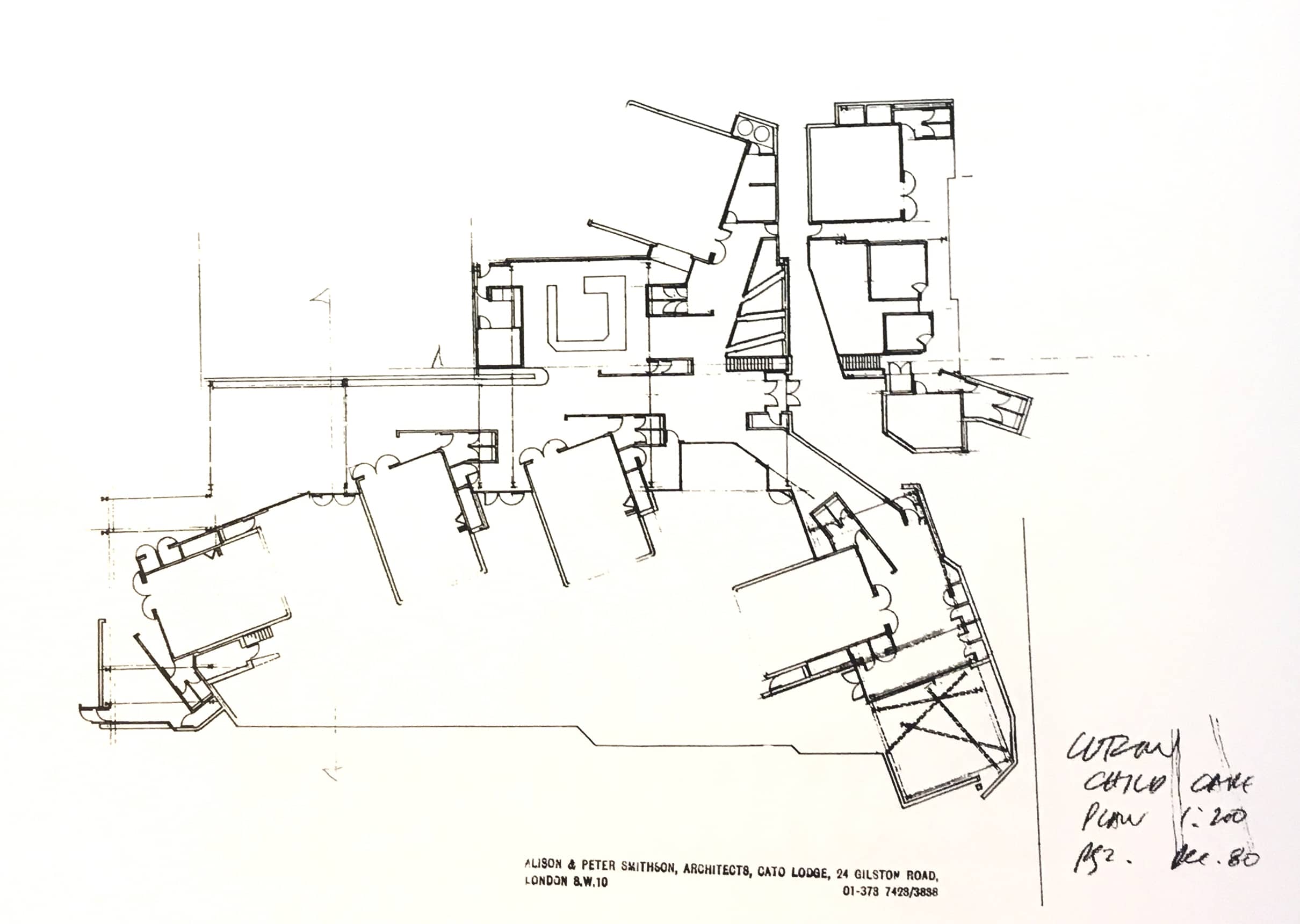

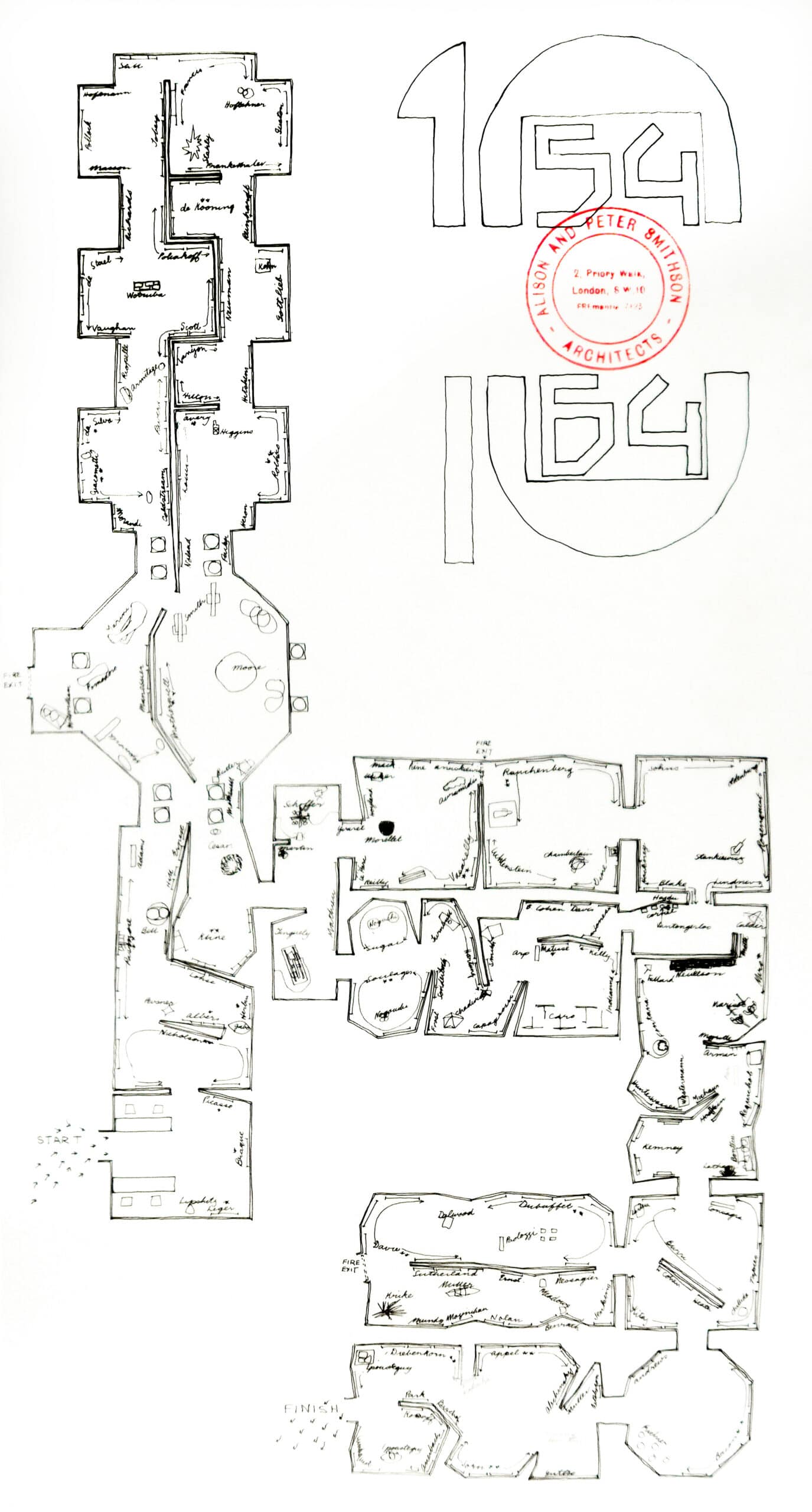

Alison Smithson’s ‘Painting & Sculpture of a Decade’ Exhibition, 1964. Preliminary drawing by Alison Smithson.

The beginning of the imagery of ‘the shift’ in the late 1960s can also be seen in the cut-outs, layers, and arabesques of this tissue paper series, and particularly in the ephemera of 1964 and 1968. The Smithsons refer to these experiments as the seed of the ideas that prompted them to contemplate a shift in their architectural approach.[13] It is also surprising how much nature is present in these cards. Nature becomes a key element in another set of Christmas cards of importance, the set known as ‘the ephemera of the shift achieved’ which includes the cards of 1969, 1970, 1971 and 1973.

Conifer trees and evergreens have always been present in Christmas decorations, harking back to the pagan origins of Christmas and the Roman festival of Saturnalia. The Smithsons repeated use of nature in the graphics of their Christmas cards is not only a link to tradition; a close look at this series of Christmas cards reveals that nature is never far from their thoughts, as material for projects, as a source of inspiration or as a vehicle for conveying their ideas. As with the Christmas cards themselves, these elements of nature are an inherent part of the creation of the couple’s architecture, both during the design phase and when it is built, specific elements that contribute their own character and content.

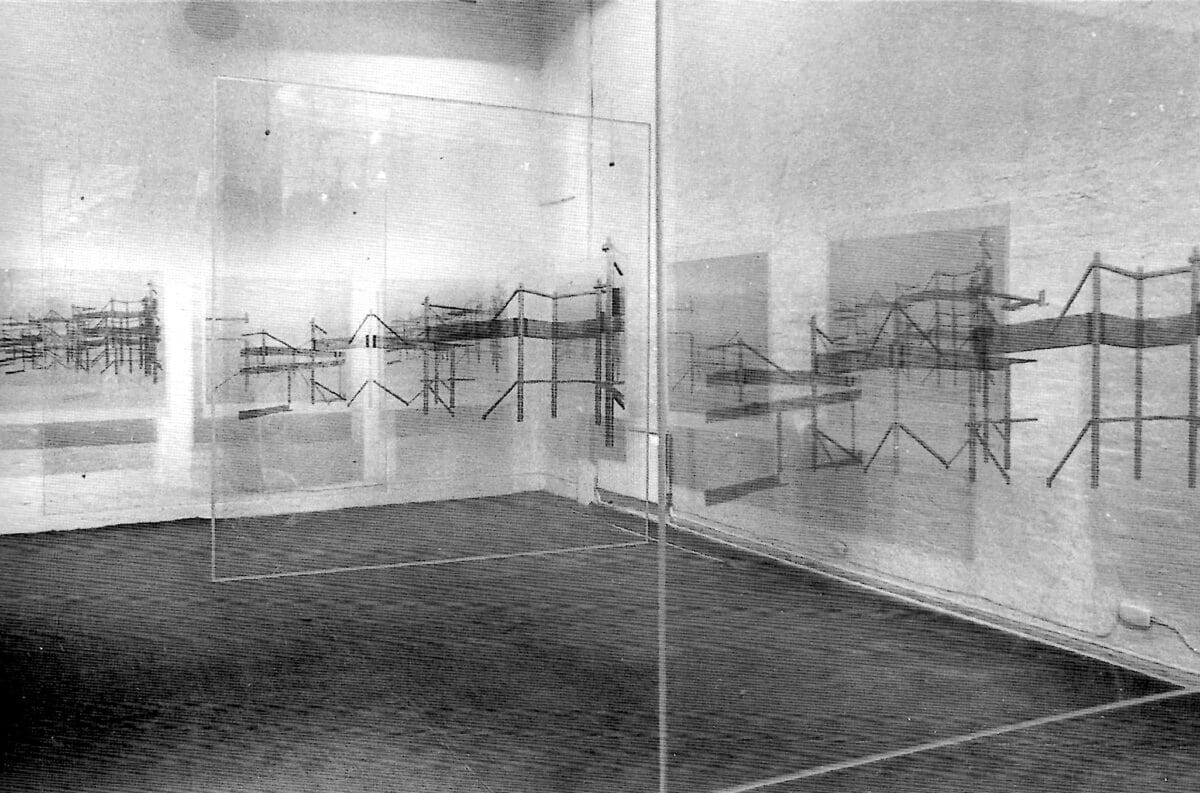

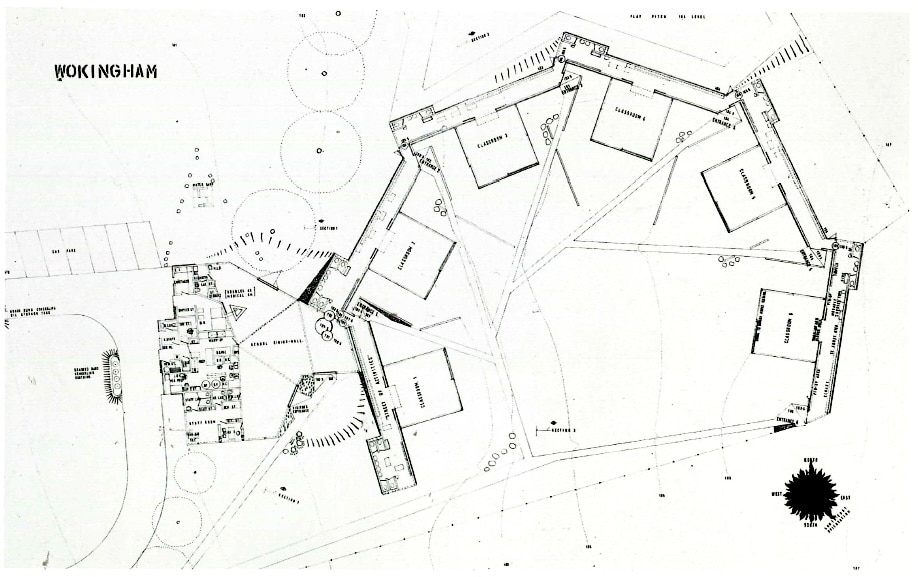

For example, they use the Jubilee Christmas card (1977), although it didn’t feature any plant elements, to experiment with the graphic equivalent of the ‘connective forms’, a series of angled guidelines—paths, trees, expanses of water—that are connective landscape forms or ‘signs of occupancy’, used earlier in their proposals for the Wokingham Infant School (1958) and Churchill College (1959).[14] These connective forms are resuscitated twenty years later as a graphic resource for the Christmas card, just as they are being folded and raised skywards in their Kingsbury Lookout entry for the Art into Landscape competition (1977). These ideas were finally realised in conjunction with Axel Bruchhäuser in several projects both at the Tecta factory and at the Hexenhaus.

Nature, the seasons, inhabitants and indeed the many shapes and forms of life itself, are regarded first as ‘signs of occupancy’; then as decoration, which could be an art form, the art of inhabitation; finally becoming the matter and materials that comprise the architecture, a collective work of art. In the pages of The Shift the Smithsons use their work with ephemera, and their Christmas cards, as real materials with which to build a narrative of past experiences and from there to continue to develop their concept of architecture:

The shift to thinking about events, and about decorations made for the day, gradually extended the aesthetic of the light touch into the making of designs in which overlay or lattice form part of, or supplement, longer lasting structures and suggest the possibilities of design contributions to their inhabitants: between layers there seems to be room for illusion and activity.[15]

Christmas cards occupied part of that ‘room for illusion and activity’ much more deliberately after that retrospective review of their work and began to feature regularly in their conferences, articles and exhibitions as an ingredient that was both necessary and essential in order to understand the scope of their work—so much so that the last retrospective exhibition of their work, held at Galería BD in Madrid in 1992, featured a display of more than twenty Christmas cards, given equal prominence to the displays of the rest of their projects, books and furniture.

Alison saw every Christmas card as a chance to immerse herself in the spirit of Christmas, look forward to the future, reflect on the past, and maintain the sense of expectancy that Christmas holds. From the 1980s onwards, the Christmas cards gradually ceased to be two-dimensional and became miniature constructions that increasingly reflected their cryptic, poetic content. In the words of John Berger:

… each confirmation or denial brings you closer to the object, until finally you are, as it were, inside it: the contours you have drawn no longer marking the edge of what you have seen, but the edge of what you have become.[16]

The Christmas cards, although just one facet of Alison and Peter’s home life, turned out to be, as they themselves said, ‘underground streams which will feed our architecture maybe years later. In this sense they are genuine ephemera, something in the air and drifting by to be caught, looked at and released into other work.’[17]

This book is an invitation to readers to delve into the cryptic messages that Alison painstakingly made and sent out with love each Christmas. It is also intended to enable a deeper understanding of the Smithsons’ personal work. Think of it as a spark for new recipes of a pudding, to be re-created time and time again ‘with infinite variations; without imposed boundaries; capable of recognising unfolding orders…’,[18] generation after generation, acknowledging ‘a new beginning, as a bride is dressed and as a “white” Christmas is offered as a symbol of renewal’.[19]

Ana Ábalos Ramos, architect (2004) and PhD in Architecture (2016), combines her professional practice with teaching at the Department of Architectural Projects at the Universitat Politècnica de València (Spain) and academic research. Her doctoral thesis ‘A&P Smithson: The Transient and the Permanent’ and subsequent scholarly output, encompassing articles, books, and exhibition curation, explores the contemporary relevance of Alison and Peter Smithson’s legacy, with particular focus on their approach to processes of spatial appropriation in domestic and urban environments.

Notes

- Peter Smithson, ‘Restaging the Possible’, ILA&UD Yearbook (1995), 42–49.

- ‘Set of Mind’ in Alison and Peter Smithson, Italian Thoughts (1993), 101.

- The Shift is the title of a special issue of Architectural Monographs devoted to the Smithsons’ work that also contains an essay by the Smithsons documenting what they term ‘the shift’. Therefore, ‘the shift’ is at the same time the title of a book, of an essay and a term coined by themselves to express a new approach in their own work. Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, Alison + Peter Smithson: The Shift, ed. by David Dunster, Architectural Monographs No.7 (London: Academy Editions, 1982).

- Juhani Pallasmaa, ‘The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture’, Architectural Design Primer (New Jersey: Wiley, 2009), 29.

- Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, Alison + Peter Smithson: The Shift, 59.

- Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, ‘The “As Found” and the “Found”’ in David Robbins, The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990).

- They specifically mention the close connection between the ‘as found’ aesthetic and the Christmas cards of 1973, 1974, 1975 and 1976. Alison + Peter Smithson: The Shift, 56.

- This design was also staged as ‘A Line of Trees… A Steel Structure’. Art Net Gallery, London. October 1975. Net Works Edinburgh, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh. 7–28 February, 1976.

- a.s.o an acronym for ‘and so on’.

- Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, Urban Structuring: Studies of Alison & Peter Smithson, A Studio Vista/Reinhold Art Paperback (London: Studio Vista, 1967), 34.

- Alison Smithson, ‘Louis Kahn: Invitation to Otterlo’, Arquitecturas BIS, 41–42 (1982), 62–63.

- This characteristic can be seen especially when looking at the photos that the Smithsons took each year grouping the Christmas cards together and which accompany the timeline at the end of this publication. In them it can be clearly identified how, from the 1978 postcard onwards, they began to incorporate the three-dimensional variable into the composition.

- Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, Alison + Peter Smithson: The Shift, 63.

- The object suggests how it can be used, the user responds by using it well—the object improves; or it is used badly—the object is degraded, the dialogue ceases.’ Peter Smithson and Allison Smithson, ‘Signs of Occupancy’, Architectural Design (1972), 91–97.

- Alison and Peter Smithson, Alison + Peter Smithson: The Shift, 67.

- John Berger, Berger on Drawing, ed. by Jim Savage (Aghabullogue Co. Cork, Ireland: Occasional Press, 2007), 3.

- Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, Alison + Peter Smithson: The Shift, 10.

- Peter Smithson, ‘Conglomerate Ordering’.

- ‘Staging the Possible’ in Alison and Peter Smithson, Italian Thoughts, 22.