The Italian Job: Anthony Salvin, Sir John Benson and the Royal Cork Yacht Club, Cóbh

Anthony Salvin (1799–1881) was a noted English architect of country houses and a pioneer restorer of historic monuments. In the latter sphere, he undertook significant interventions at Windsor and Alnwick Castles and at the Tower of London. For example, he is largely responsible for the way we see the yards of the Tower today. Whilst, we may now question some of his practices in this regard, his integrity and the conscientious manner in which he went about his work, within the best understandings of his time, cannot be doubted.

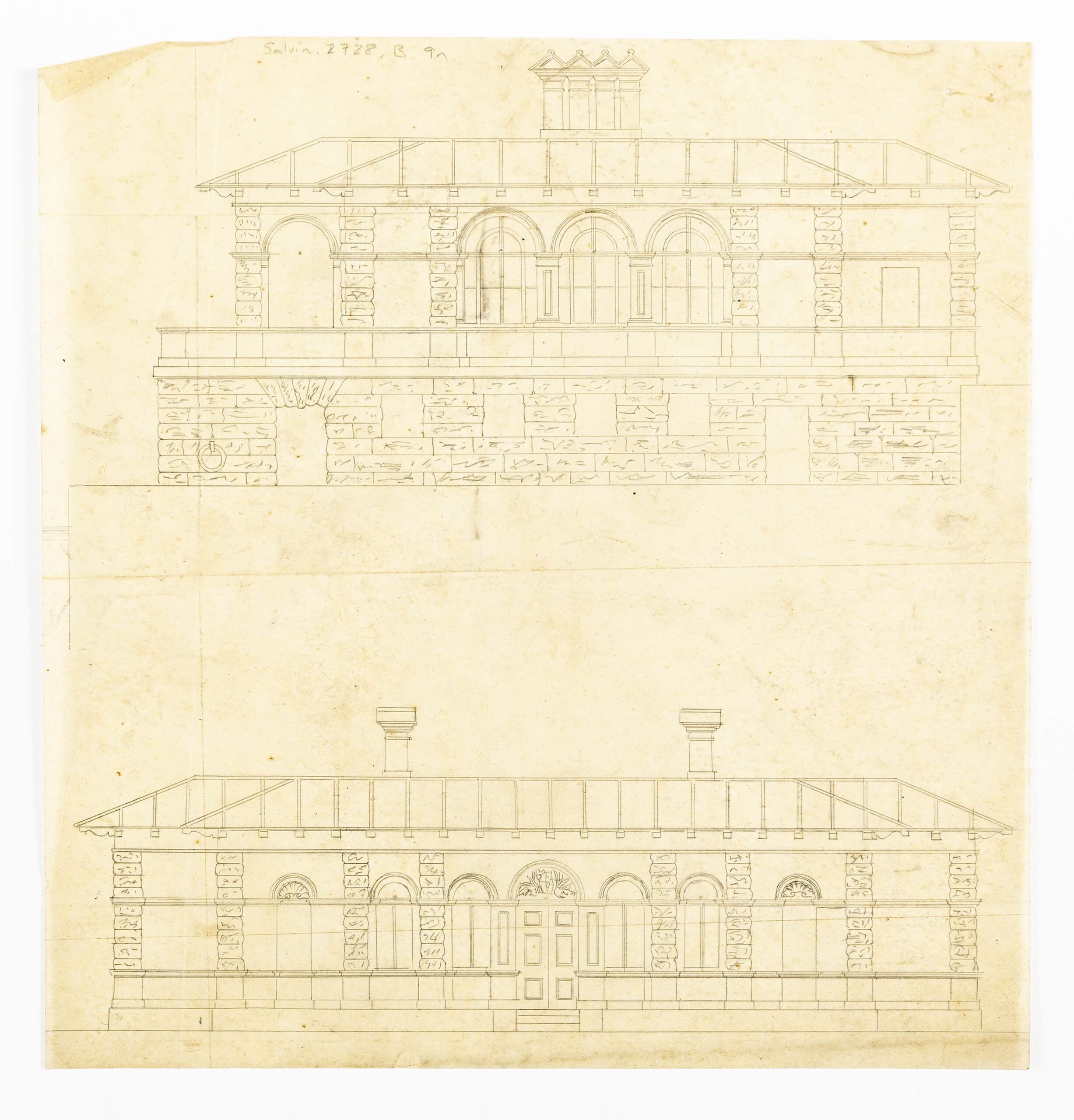

According to his biographer, Jill Allibone, Salvin’s ‘reputation had been established for careful, archeologically correct work on old houses and churches’ and ‘his business was to a great extent based upon the patronage of the landed gentry and aristocracy’. [1] His reputation for country house work is dominated by large set piece projects such as Harlaxton Manor in Lincolnshire (1832 on). All his great houses are in historical styles, largely Elizabethan. He almost exclusively worked in England. However, Salvin’s name had also been associated with one building in Ireland, the former clubhouse of the Royal Cork Yacht Club (RCYC), in Cóbh, Co. Cork, constructed between 1852–54. [2] The club was originally founded in 1720 and received their ‘royal’ from William IV in 1831. The clubhouse’s distinctive Italianate style is a perfect match for its south-facing, seaside location and original use.

The building is presently operated as Sirius Arts Centre: a gallery and artist’s residence. The organisation’s team had been curious about the provenance of their unusual building. In the spring of 2021 they sent a set of elevations, plans and working drawings of their premises to be restored, supported by a grant from the Heritage Council (Ireland). Despite the fact that the provenance of the building seemed solid, [3] there were a number of niggling questions. Why was Salvin designing a building in Ireland so far from his home? Why was he designing an Italianate confection when he was so comfortable with castles and manors? Why was a local man, Sir John Benson, being credited with the design work up to the eve of its opening and why were the drawings all signed by the contractor, not Salvin? What was the builder’s role in the design? Lastly, another Cork architect and builder, Henry Hill was appointed Superintendent – what (if anything) was his contribution? To try and answer these questions, I was commissioned by Sirius Arts Centre to verify the authorship of the RCY Club house.

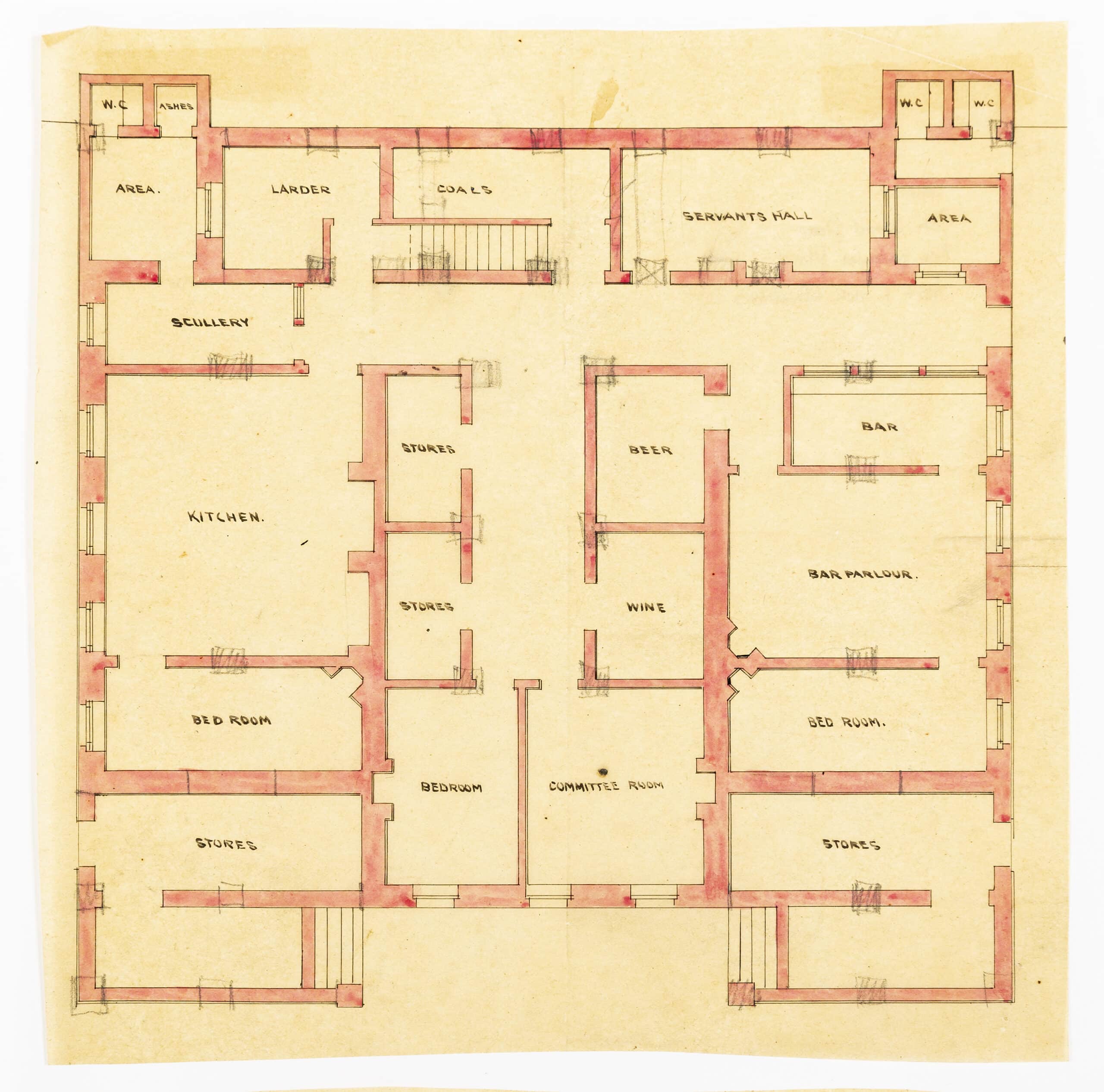

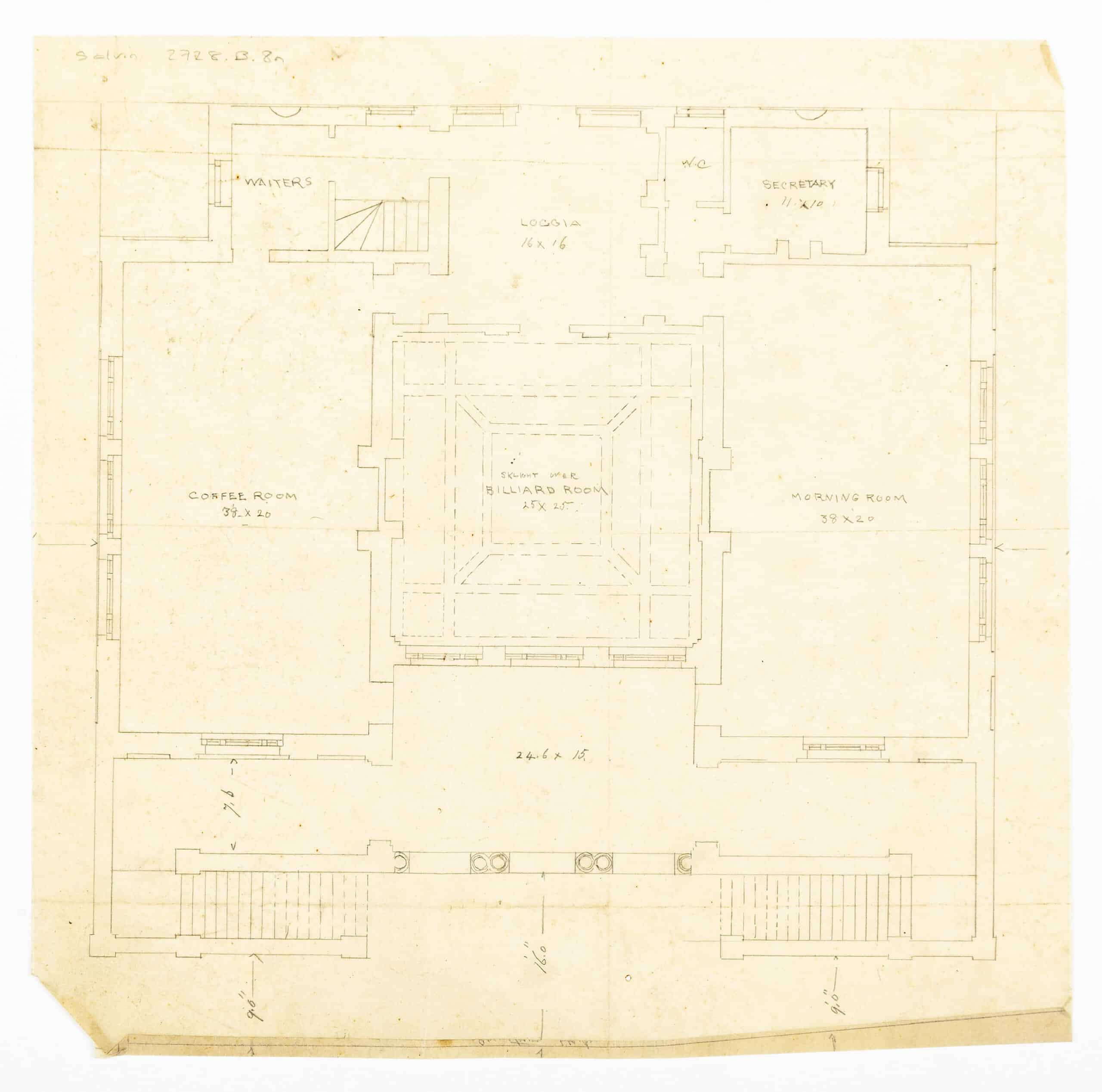

The first port of call was the building itself. The Programme Manager & Producer, Brian Mac Domnhaill, explained how the original building had been extended, sub-divided, sold off in sections, partly-demolished and partly restored in the 167 years since it was completed. The heart of the building is its spacious first floor rooms which are largely unaltered. These consist of a morning room (to the east), a billiards room (in the centre) and a coffee room (to the west). Elsewhere there was greater confusion about the original layout of the rooms which recent restoration work is seeking to unpick. As the original plans were at the conservators, a review of a digital record created prior to conservation was studied which clearly showed the signature of Michael Cassidy, known to be the contractor.

Cassidy was a significant figure in Cork, who had been involved in some high-status buildings, but who had run into legal difficulties in the 1860s and become insolvent. [4] However, there was another name on the drawings ‘WM Maunsell, per Jas H Smith-Barry’. Alicia St Leger has shown that William Maunsell was the estate agent of a local Anglo-Irish landowner, James Hugh Smith Barry, and Jill Allibone reported that Smith-Barry and Salvin had known each other since at least 1846, when the Salvins visited him at Fota House, Cork. [5] There was a strong indication that Salvin was indeed the originator of the plans. However, St Leger had also traced the long-drawn out design process of the clubhouse, the influence Smith-Barry had over it and the role of Benson in the earlier stages before he was unceremoniously bounced off the job. (Something similar had happened to Salvin himself over the Carlton Club competition in 1844). [6] Further research found mention of Benson designing the clubhouse in 1851, [7] and being mentioned as the designer as late as April 1853. [8] It would certainly have been more convenient for him to have undertaken the role. Could the design as built owe something to Benson? The building superintendent, Henry Hill, was a colleague of Cassidy’s which might have made for a cosy working arrangement, but his design role seems to have gone no further than detailing the perimeter railings and walls. [9]

Allibone’s biography (1988) included a tantalising mention in the appendix that there was a drawing of the clubhouse in the collection of one RC Fiske. A Reginald C Fiske, a collector of material relating to Norfolk and expert on Nelson, had died in 2018, was he the same man? Unfortunately Dr Allibone died in 1998, so her source could not be confirmed. If the drawings existed and matched those in the Sirius collection, it would go a long way to confirm the authorship.

After a number of false trails and dead ends, it became apparent that Fiske had published a paper on ‘The stables on the Old Shirehouse site of Norwich Castle bailey’ [10] which a University of East Anglia historian, Dr Clare Haynes, had included in a list of documents related to that castle. When contacted, Dr Haynes explained that a part of Fiske’s collection was auctioned in a two-day event held by Keys Auctions in Norfolk in 2016. Furthermore, a collection of drawings credited to Salvin was included in the sale. According to the auction catalogue, the drawings had passed through the hands of Sir Samuel Hoare and a bookseller, Howard Rosewell. Was this the source Allibone had used, and were the RCY Club house sketches within?

Auctioneers are rightly wary of giving information out concerning buyers, but after a number of phone calls and gentle reminders to the auction house, Ms Anne Pegg was able to explain (after confirming with the buyers that they were happy to be contacted) that the collection had been purchased by Drawing Matter. The Drawing Matter team quickly confirmed that there were drawings in the collection which related to the clubhouse and comparison with the Sirius collection showed they were in the same hand and of the same building.

The question of the clubhouse’s seemingly un-Salvinesque style also seemed to be fading in importance. Cóbh (then called Queenstown) is a seaside place which had deep contacts with the Royal Navy and British and Irish aristocracies. As such, it was perhaps natural that James Smith-Barry, who also had a seat in Cheshire, would specify an Italianate structure for such a location, especially after the completion of Victoria and Albert’s Osbourne House in 1851. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Architecture, ‘following such a Royal imprimatur Italianate stucco ornament was widely used to enrich the façades of terrace-houses in areas such as Kensington, London, from the mid-C19’, to which we can add other British and Irish towns, such as Cóbh. Given the coastal location of Osbourne, it is not coincidental that the style became popular for other seaside locations. Furthermore, the area of Cóbh in the vicinity of the clubhouse had been planned by Decimus Burton for the Earl of Midleton in the 1840s. [11] (Coincidentally, during this decade Burton was also working on Kew Gardens with Salvin’s brother-in-law, William A Nesfield, a landscape gardener). [12] In terms of Cóbh, the Burton plan and the RCY Club house appear to have set the style for most of the significant developments in the town for the next twenty-five years.

Furthermore, despite his love of mediaeval and Elizabethan design, Salvin was no tyrant in terms of style, and had created a small number of Italianate houses since the 1830s. The largest of these was Pennoyre in Powys, Wales, (1848), but there were others at Muswell Hill and elsewhere. However, perhaps the greatest influence on the final design came not directly from Salvin, but from a temporary structure erected near the site in 1849. In August of that year, Victoria and Albert arrived on the Royal Yacht to begin their first tour of Ireland. The timing was inauspicious since Ireland was deep into the worst year of its Potato Famine, but they were greeted by cheering crowds. On the day of their visit, ‘Her Majesty and the Prince … landed … and entered the pavilion. … Having reached the interior .., which was beautifully made up, the Queen stood in the centre of the apartment, apparently much gratified by the preparations for her reception. Although a handsome throne had been erected, her Majesty remained standing, and … at the request of the deputation of the town changed “Cove” to “Queenstown”.’ [13] A search of the Cork newspapers revealed that the small ‘Royal Pavilion’ constructed for their entertainment remained in use for a number of years by the RCYC, [14] and an examination of a painting in the collection of the Cóbh Museum showed it to be very similar in scale and general form to the clubhouse. Although it is crude, one can perceive slight Italianate leanings in terms of its loggia, and hipped roof. Less tangibly, it seems that the membership of the RCYC, who were prominent in the celebrations of the Queen’s visit, wished to crystallise in architectural form the memory of the celebrations.

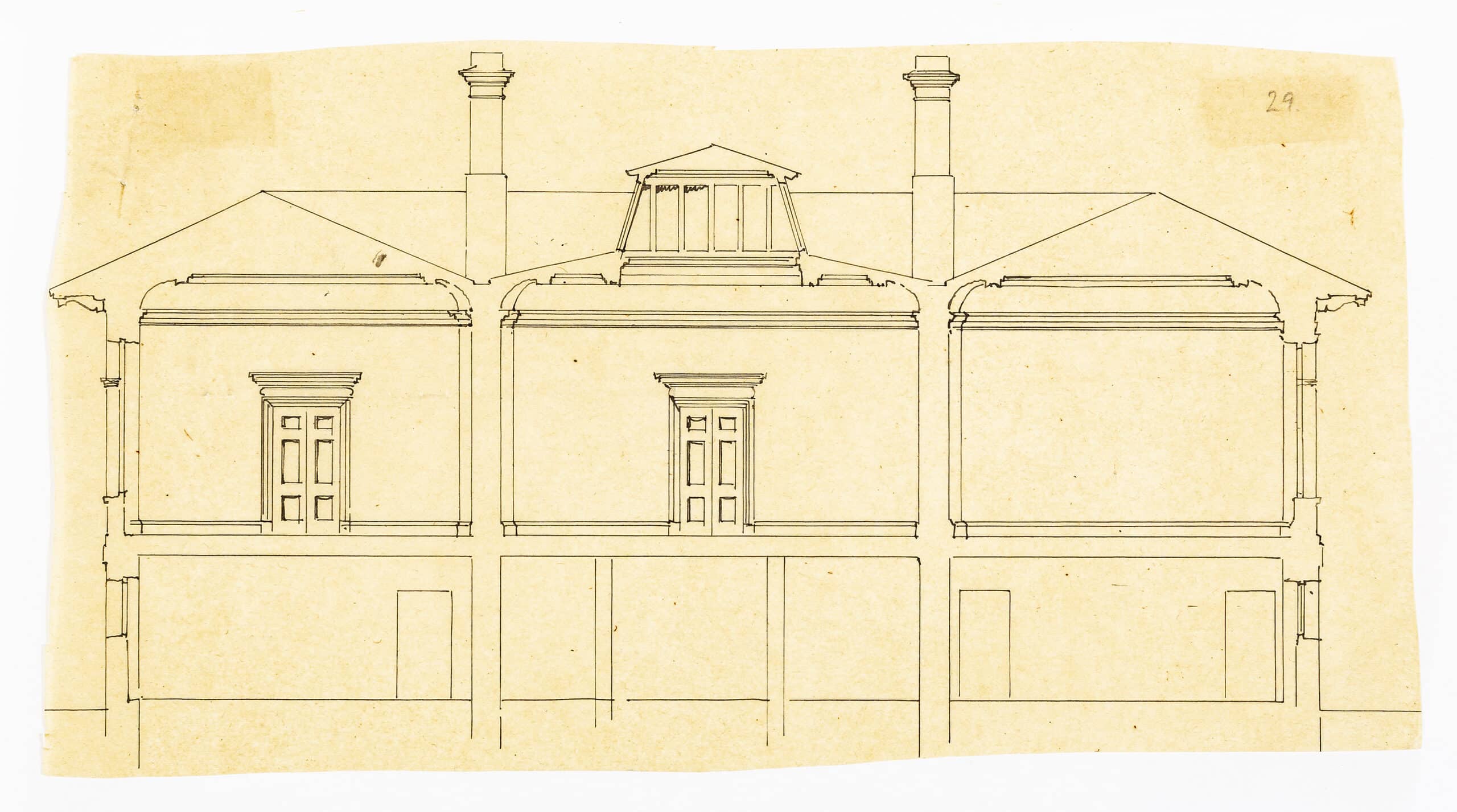

Returning to the drawings, it appears that the signatures of Cassidy and Maunsell are not intended to mark ‘authorship’ as we might expect, but to indicate an assent to their contractual obligations. Thus the drawings become an illustrated contract. As there are no signatures of any club-members visible, Maunsell seems to have acted as the client was on behalf of Smith-Barry (who, not inconsequentially, was also the Admiral of the RCYC). Needless to say, construction necessitated some further negotiation. Although the drawings show extensive rustication was intended (on the plinth and pilasters) this was replaced with smooth rendered quoins to save money. [15] The design for the entrance façade included niches with shell motifs to the tops. These were not carried through or were removed and converted into windows. Otherwise, the building is a faithful representation of the initial concept. The distinctive chimney stacks and lantern were removed in the twentieth century.

During all of the above research, the Sirius drawings remained at Muckross Bookbindery and Conservation Workshop, Killarney. In summary, this consisted of relaxing and flattening, cleaning (some were immersed in deionised water), repairs to sections of the paper, and rebinding on Irish linen hinges.

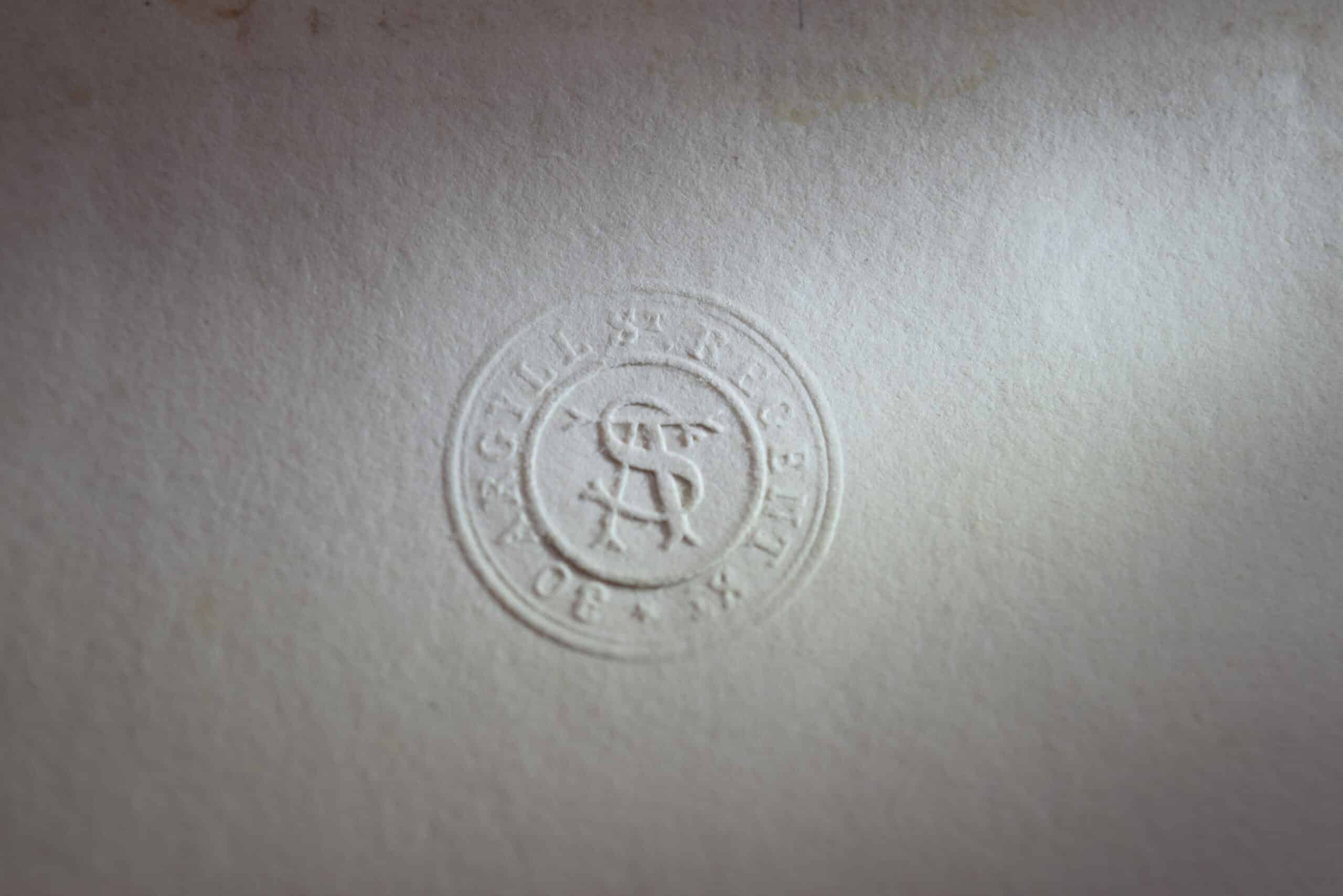

When they returned to the gallery, the images were brighter and crisper than they had been for decades. Careful examination showed a number of the sheets featured an embossed sign: ‘30 Argyll St. Regent St.’ surrounding a monogram in Gothic letters ‘AS’ – Anthony Salvin.

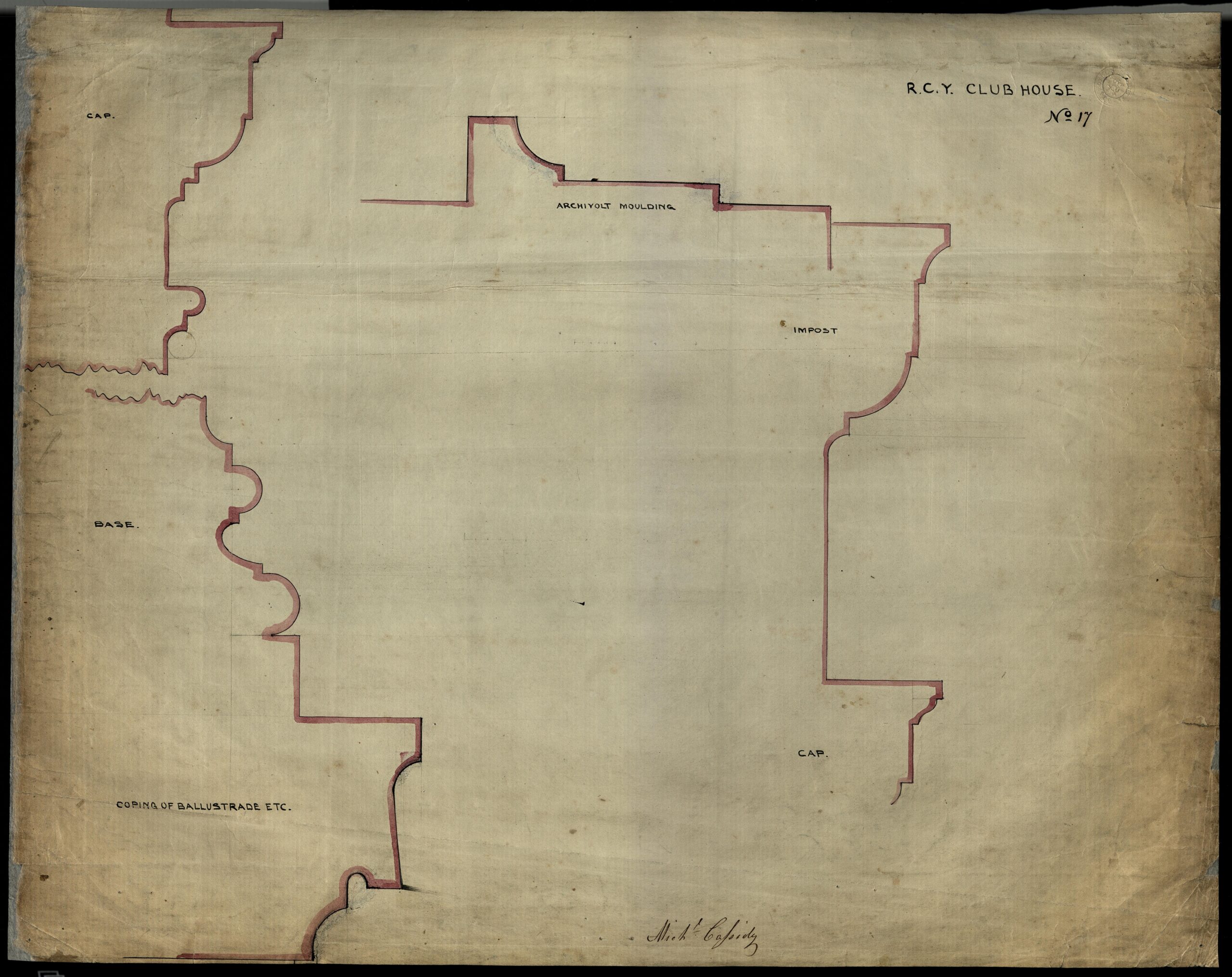

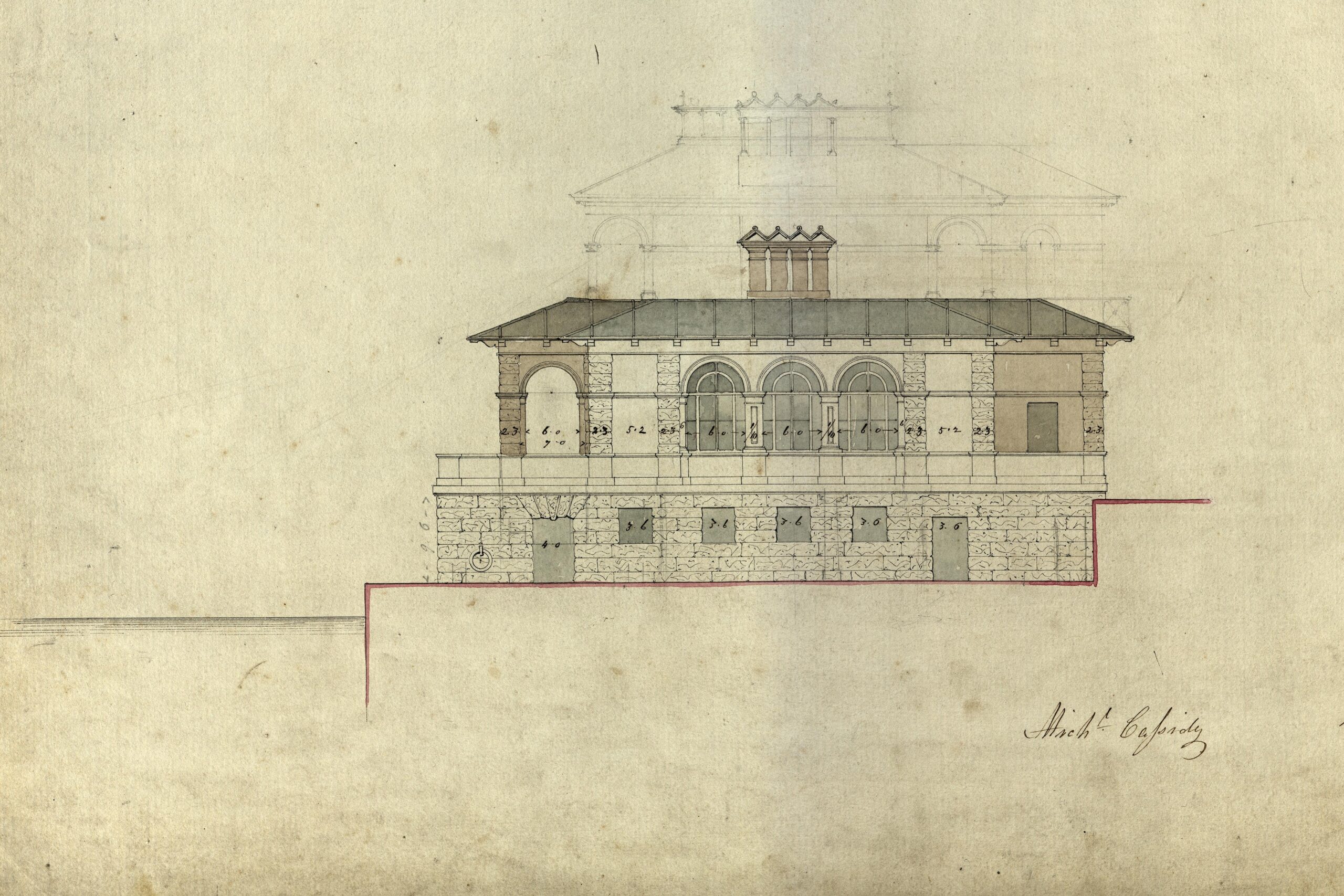

There are great similarities between the Sirius drawings and those in the Drawing Matter collection. The latter appear to be rough copies, perhaps made for studio reference, although their sketchiness could indicate that they were earlier, concept drawings. For example, the centres of the arcs in the drawing of the eastern façade are roughly punctured by the point of a compass, and the paper appears to be inferior. As Matthew Wells has shown, [16] Salvin and his staff combined sectional views, constructional details and elevations at different scales on the same sheet of paper. These presumed (and permitted) suitably experienced viewers to visualise the intended product in space, albeit the representations of that space were twisted on the page. A good example in the Sirius collection is the profile drawing for the Tuscan-inspired balustrade and arches at the waterside of the building. The continuous pink line which ghosts the profile makes objects, which in reality are made from a number of different materials, look as if they are all part of one curve. Furthermore, this profile would have been impossible to see in reality once construction was complete. A jagged break in the section on the right hand side signifies a continuous, gently-changing column profile not explicitly stated elsewhere. (Presumably the contractor’s own knowhow filled in the gap). The archivolt profile (top right) is rotated 90o out of plane and then twisted orthogonally.

The general elevations embody the usual paradox at the heart of all orthographic views viz. to be so far away that foreshortening becomes negligible (i.e. infinitely), yet so close to see all the small details. A close examination of the drawings of the plan and eastern elevation showed for the first time a series of faint sketches. The building was extended (by John Benson) with a pair of wings in the 1860s, and perhaps they relate to early discussions concerning that. However, the elevation drawing of the east façade shows ghostly marks at the top of the building. At first Mac Domhnaill and I thought they might be a suggestion for an alternative treatment for that façade – perhaps an intervention by the disgruntled Benson? Further consideration showed that someone had proposed a second floor to the clubhouse, along very similar lines to Salvin’s. Presumably, this was in the late nineteenth century when the club was in its pomp. It is known that non-sailors enjoyed watching the various races and regattas from the terrace and windows of the clubhouse, and that telescopes were provided for this purpose. From the sketch it appears that a second, panoramic viewing area was proposed, with perhaps a roof-top belvedere surrounded by cast-iron railings. Perhaps unfortunately, this did not come to pass. Benson’s influence on the executed design will probably never be known since his records were not retained and after 1861 Cassidy fades from view.

This set of drawings provide testimony, not only of architectural practice and construction technology, but evidence of how drawings have an afterlife beyond the completion of the building. The evidence suggests they served as quasi-legal documents and also formed the basis for suggestions for adaptation of the structure. They were punctured and embossed during their creation and they have been were edited and mistreated subsequently. The latest phase of their existence was restoration which has revealed more about them. The confirmation that Anthony Salvin was indeed the designer of this building and the preservation of his drawings allows us to begin to go deeper into a study of what remains within the building of his firm’s work, and what was subsequently changed. The Sirius Arts Centre are certainly the custodians of a unique, if atypical, project by one of Britain’s leading nineteenth century architects.

Notes

- Jill Allibone, Anthony Salvin: Pioneer of Gothic Revival Architecture, (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 1988), p. 152.

- ‘Cóbh’ is pronounced ‘Cove’.

- Alicia St Leger, A History of the Royal Cork Yacht Club (Crosshaven: Royal Cork Yacht Club, 2005), pp. 399–406.

- ‘City Insolvents’, Cork Examiner, June 22, 1861, p. 28.

- Allibone, op. cit., 67.

- Allibone, op. cit., pp. 59–60.

- The Builder, Vol. IX, No., 445, August 16, 1851. p. 517.

- See ‘Royal Cork Yacht Club’, Hunt’s Yachting Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 4, Apr, 1854, p.212 and Vol. 3, No. 5, May, 1854, p. 281.

- ‘To Builders’, Cork Examiner, March 17, 1854, p. 2.

- R. C. Fiske, ‘The stables on the Old Shirehouse site of Norwich Castle bailey’, NARG Newsletter 36, 1984, pp. 1–5.

- ‘Improvements at Cove’, Cork Examiner, March 26, 1845, p.3. See also St Leger, op. cit., 399 & Anna-Maria Hajba, An Introduction to the Architectural Heritage of East Cork, (Dublin: Government of Ireland, 2009), 75.

- Allibone, op. cit., p. 66.

- Belfast Newsletter, 7 August, 1849. p1. It was changed back to Cóbh (pr. ‘Cove’) in 1920.

- It appear to have stood for c. two years. See ‘Cork Harbour Regatta’, Cork Examiner, 1 July, 1850, p. 1.

- £73 on a job initially costed at £1,800. St Leger, op. cit., p. 404.

- https://drawingmatter.org/anthony-salvin/

Acknowledgements:

Although the power of search engines and the internet has made this type of research swifter and simpler, it would be impossible without the kindness and help of the people who voluntarily assisted in this project. My thanks are extended to them.

Mr Niall Hobhouse, Drawing Matter

Dr Alicia St Leger

Ms Anne Pegg & Mr Andrew Bullock, Keys Auctions, Norfolk

Dr Clare Haynes, UEA

The Staff and Trustees of Cóbh Museum

This research was supported by a grant provided by The Heritage Council (Ireland) to Sirius Arts Centre.

Tom Spalding earned his PhD at the Technological University Dublin for his study of the design history of Cork city. He holds a Master’s degree from the Royal College of Art, although his primary degree was in mechanical engineering. His books include A Guide to Cork’s Twentieth Century Architecture, Layers: the Design, History and Meaning of Street Signage in Cork and Other Irish Cities and The Cork International Exhibitions, 1902-1903 (with Daniel Breen). His work as a freelance historian includes contracts with the University of Leicester, local authorities, galleries and private enterprises. Tom.spalding.cork@gmail.com.