The Master Builder: William Butterfield and His Times

It’s the sign of a good book about an architect that you want to drop everything and go out to visit, or re-visit, their buildings. And a sure indication of a good book that reproduces many architectural drawings is that you want to be able to pore over the originals in detail. Nicholas Olsberg’s recent book The Master Builder: William Butterfield and His Times more than passes both these tests. He writes with compelling enthusiasm about the work he describes, is passionately engaged with the buildings and their settings that he has experienced, and backs up his advocacy with research that has clearly occupied him for many years.

The book does not seek to supersede Paul Thompson’s William Butterfield: Victorian Architect, of 1971, which remains an important monograph, but it will be an essential complement in any serious architectural library. Fifty-four years later it is still necessary to counter a view that emerged in Butterfield’s lifetime (in criticisms by Godwin, for instance) and was reinforced by influential twentieth-century historians, such as John Summerson and Nikolaus Pevsner, that Butterfield sought to be ugly and shocking and was insensitive to context. There is no evidence for this: repeatedly Olsberg argues that Butterfield exercised a rigorous discipline in his composition, developed forms and decorative schemes derived from a serious iconographic programme, and adapted his architecture to respond to the context in which it was placed and the needs it sought to meet. If the result was unusual and sometimes shocking, so be it—though if those who were disconcerted by what they saw could forget their prejudice and look a little closer they would surely change their views.

In the minds of architects and those interested in the history of architecture, two aspects of Butterfield’s achievement probably stand out. First there are substantial buildings such as those for Keble College, Oxford, and Rugby School and his best-known church, All Saints Margaret Street. Secondly there are his modest estate cottages, at Braunstone, Heckfield, Aldenham, Fulham and elsewhere, that can be seen as anticipations of the English Free School, in being free from readily identifiable historic references and quite pragmatic in adopting (or in many cases re-using) conventional motifs such as flat-headed sash windows: Philip Webb learnt at least as much from his friend William Butterfield in the Red House for Morris as he had from his former master, George Edmund Street. Olsberg adds to our appreciation of both these aspects of Butterfield’s work. In his Prologue he explains how, as a pupil from 1956 at Rugby school, he felt out of step with his contemporaries; he trained his eye ‘to attend with care to the haptic fascinations’ of Butterfield’s surfaces and would:

… arrive early for Sunday evensong to watch the light come through the claws of the chapel apse; and spared no chance to wander the Temple Reading Room alone and sit with a book beside its great marble hearth as the western light faded through the leaded windows. (p.7)

There’s a positively Ruskinian character to this prose, which crops up at moments of extreme emotion. Here, Olsberg echoes Ruskin’s sense of the moral duties incumbent on an imperial power, in praising the near Byzantine effect of Butterfield’s mosaic interiors at St Mary’s, Dover:

…Butterfield’s farewell work of reconstitution provided for those at arms in the modern empire a haptic memory of fifteen hundred years in the history of the nation and its churches, lest they forget the cause of civilisation that should guide their mission. (p.244)

Olsberg admires and illustrates the cottages with equal enthusiasm though with less elevated prose. His book is as rigorously assembled as a Butterfield plan: eight sections of three chapters each, the twenty-four chapters being arranged thematically, but also roughly chronologically. And there are 312 illustrations: numerous previously unpublished drawings from many sources, including 40 from his own collection, 38 from the Getty, 28 from the RIBA/V&A and 11 each from the CCA and Drawing Matter archives, some of which, on the significant additions and re-fashioning of Heath’s Court, have been discussed here already. He closely examines and describes the many beautifully produced drawings from Butterfield’s office, along with period images (this below, for instance, of around 1920 by H.S. Goodhard-Rendel of a double cottage at Sessay). Pages of fine colour photographs by James Morris intersperse the chapters to reinforce his argument—seventeen of them between pages 364 and 375, for instance, to show ‘The art and craft of rural living’, following Chapter 22 ‘Cottage Lodge and Country Retreat’.

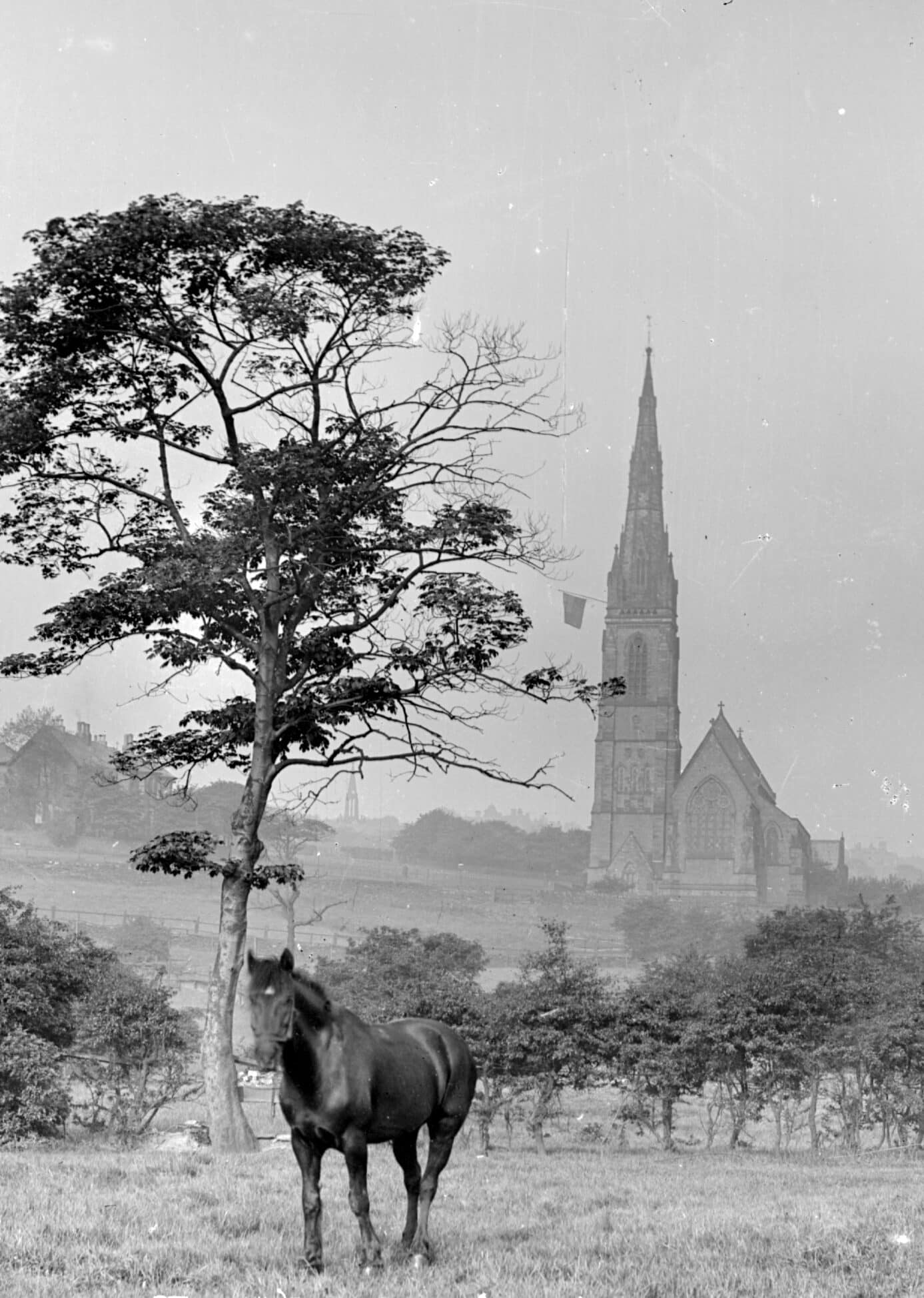

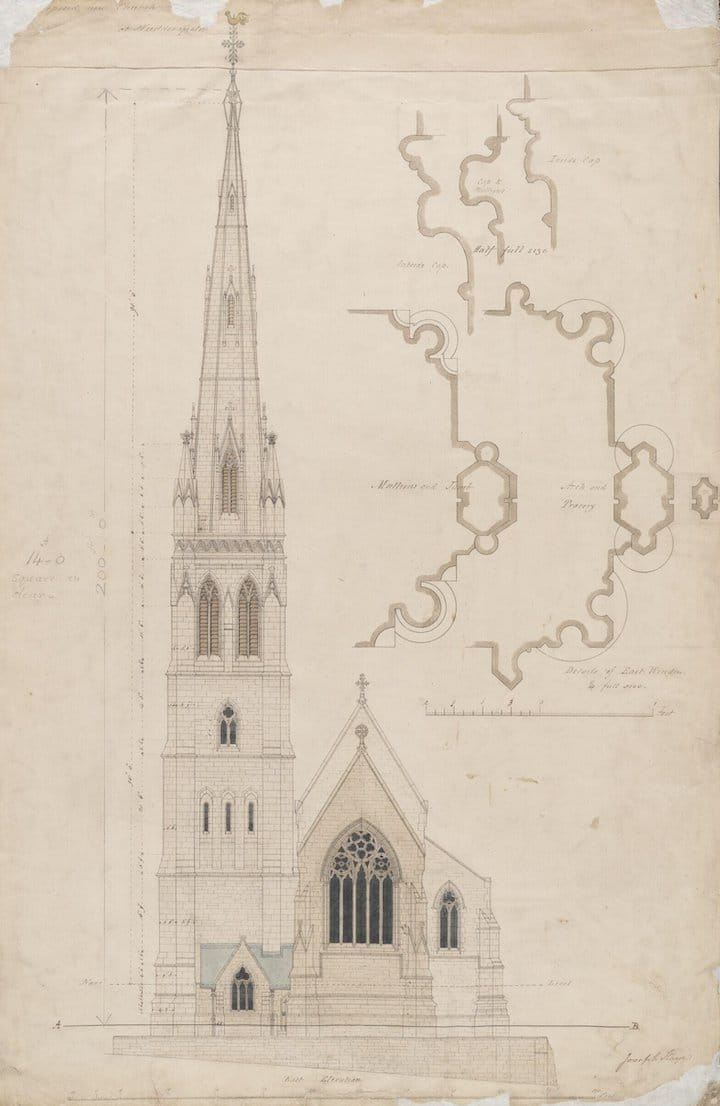

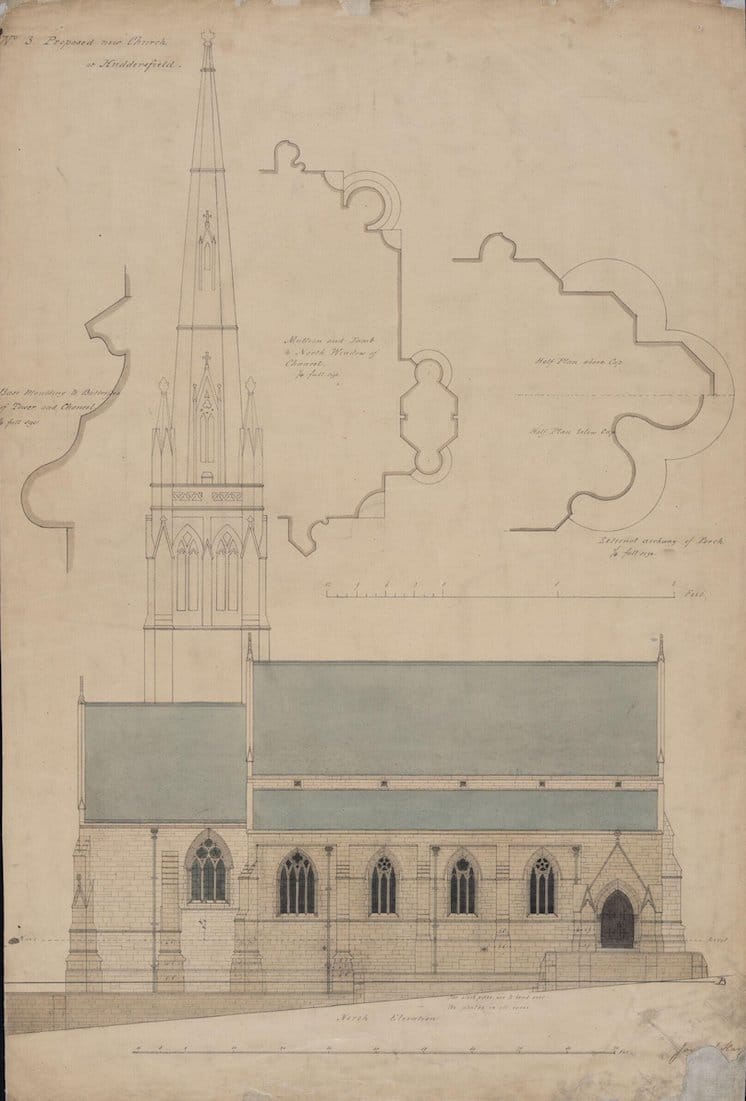

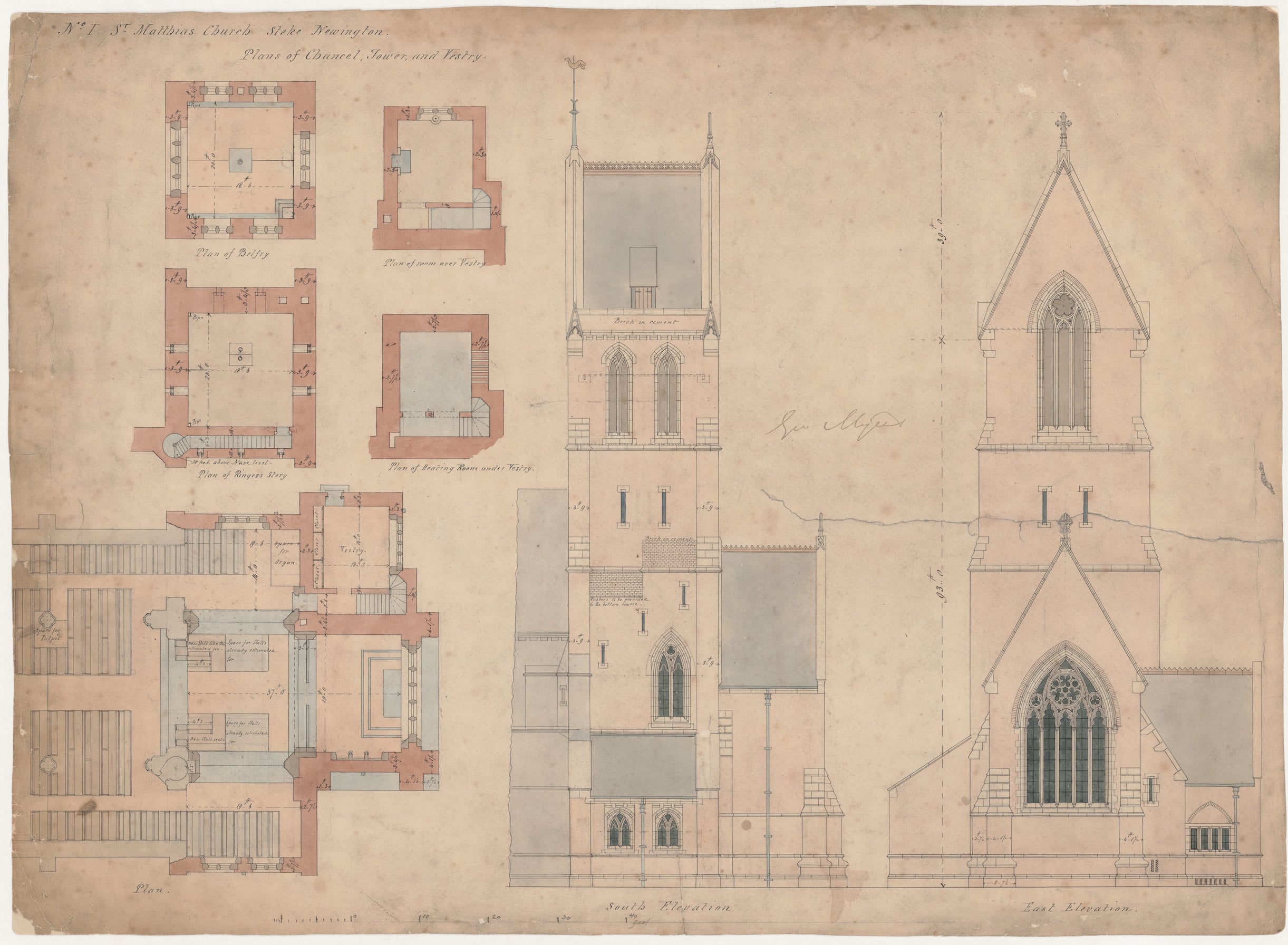

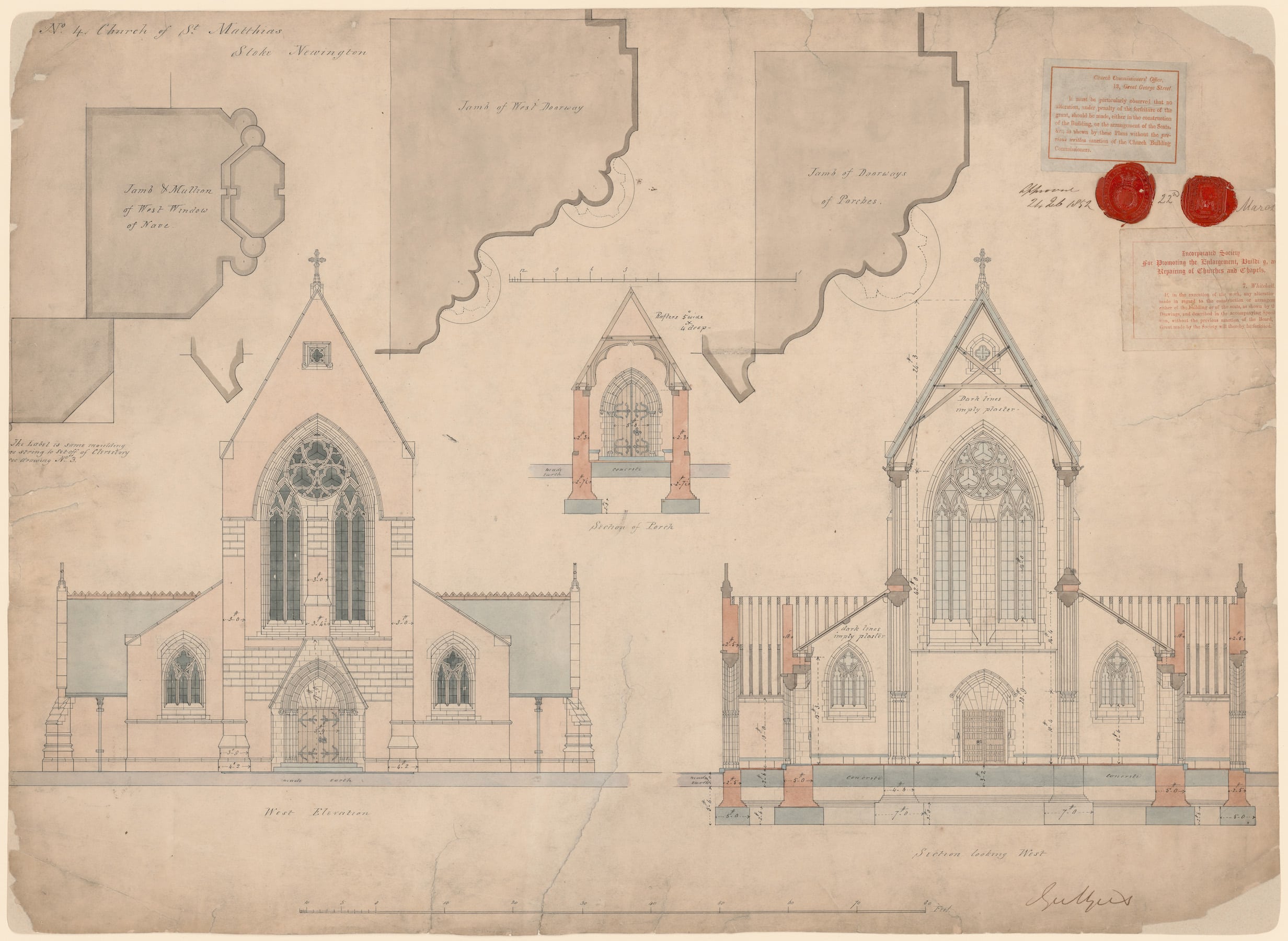

Olsberg reveals the range of Butterfield’s output, even when answering an apparently similar brief. It seems in any particular job he saw a principal task as establishing the character of the building he aimed to produce. The overall silhouette of the building, its decoration (always dependent on its iconographic scheme) and the detailed profiles of the mouldings are often summed up in a single sheet of drawings: compare the drawings of St John’s Huddersfield of 1848–51, romantically photographed around 1890 by Smith Carter, with St Matthias Stoke Newington (contract drawings under seal, incidentally)—an altogether different conception with its extraordinary saddleback tower and a west doorway achieved by plunging through the central pier dividing the window above.

Despite its 430 pages, the book does not pretend to be comprehensive. Each chapter gives references to the sources consulted and on occasion Olsberg simply directs the reader to material that he does not cover. Unlike several of his contemporaries, Butterfield designed only one major country house, for his sister and brother-in-law at Milton Ernest, Bedfordshire. The estate houses are described and illustrated in some detail but for the house itself the reader is referred to Mark Girouard’s 1969 article in Country Life (which became the basis of a chapter in his 1971 The Victorian Country House). There were occasions when for this reader the detailed description of Butterfield’s composition could have been helped by plans (Heath’s Court, for instance, or the overall layout of Keble) to supplement the lovely rendered sections and elevations. But Lund Humphries has served Nicholas Olsberg well in this beautifully produced book, and he has given his readers a volume that does full justice to the architect whose works have always moved him so much.

Nicholas Ray is an Emeritus Fellow of Jesus College and a Visiting Professor at the University of Liverpool.

The Master Builder: William Butterfield and His Times is published by Lund Humphries. Purchase a copy of the book, here.

In the second episode of series two of British Art Matters, Dr Christina Faraday speaks to Nicholas Olsberg about his insightful and comprehensive survey of Victorian architect William Butterfield.

– Hugh Strange