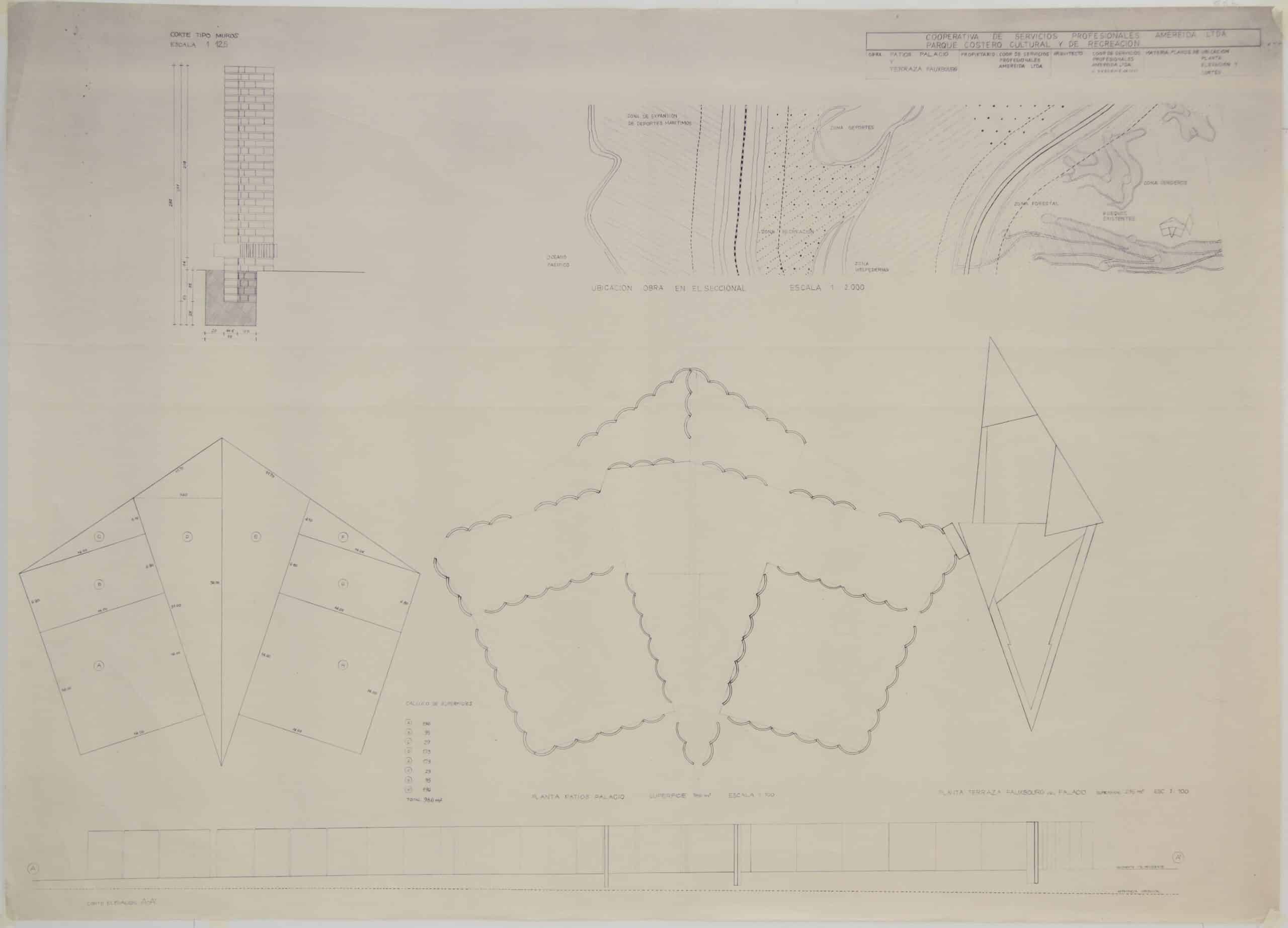

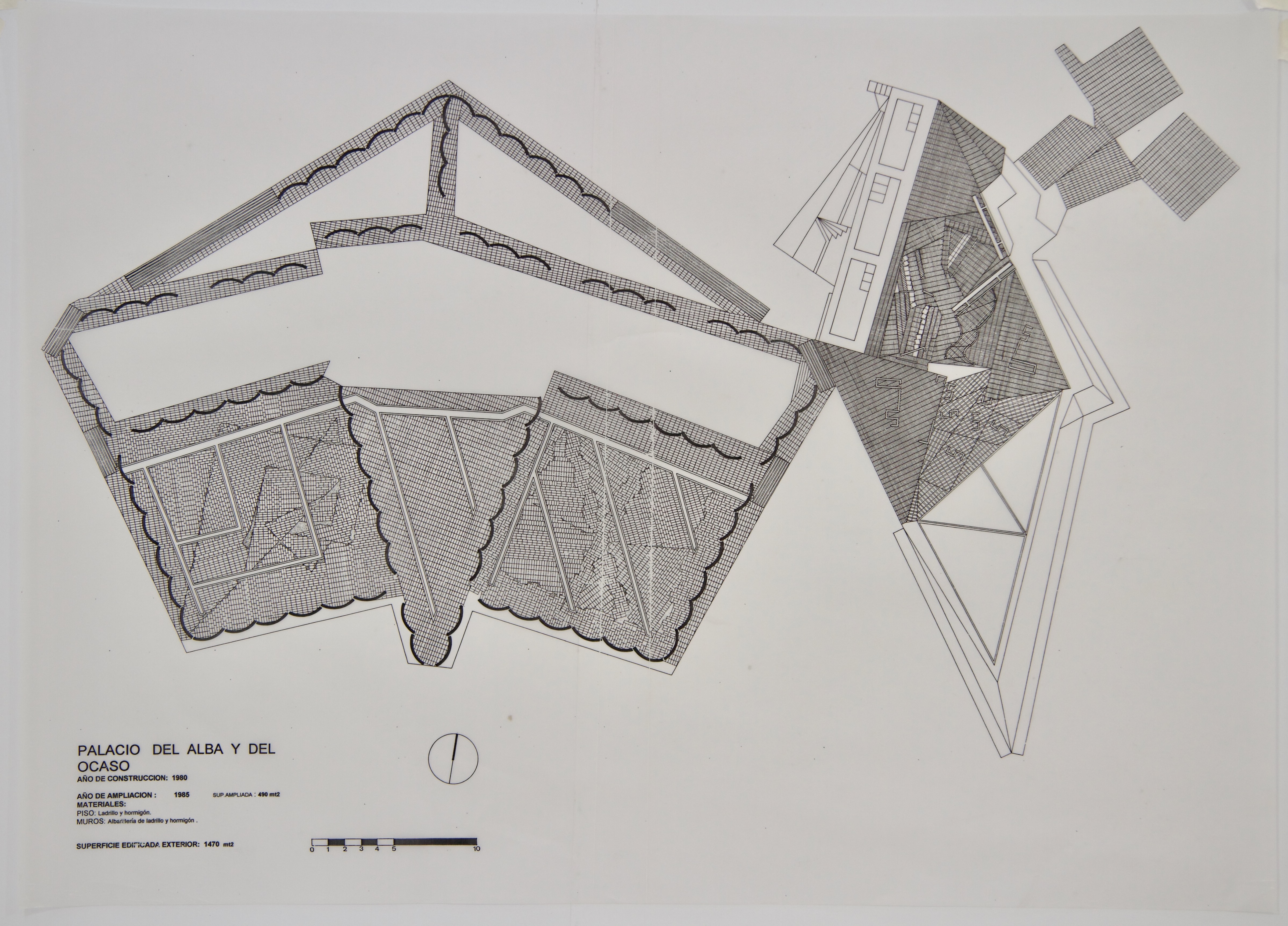

The Palace of Dawn and Dusk / Palacio del Alba y del Ocaso

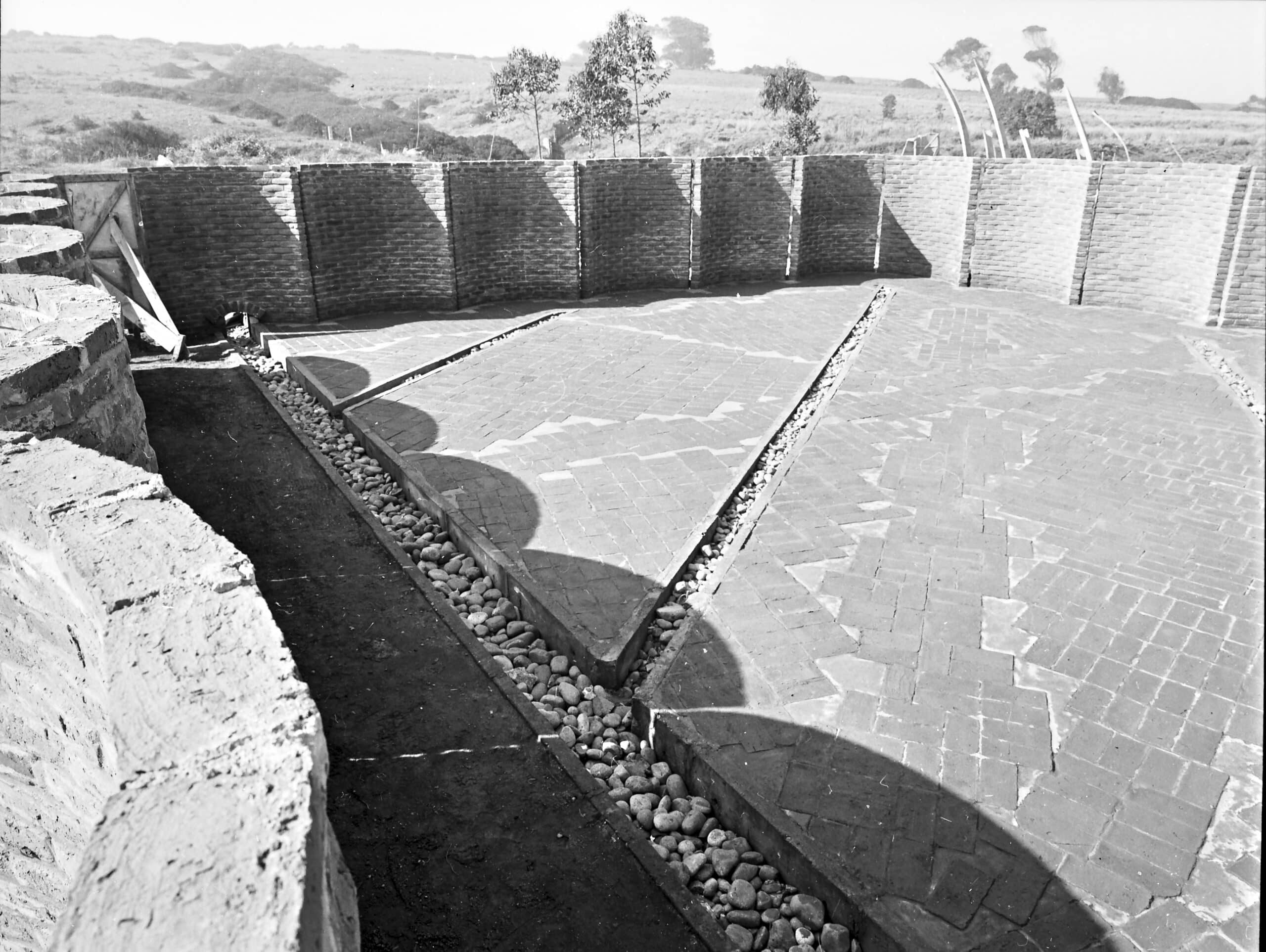

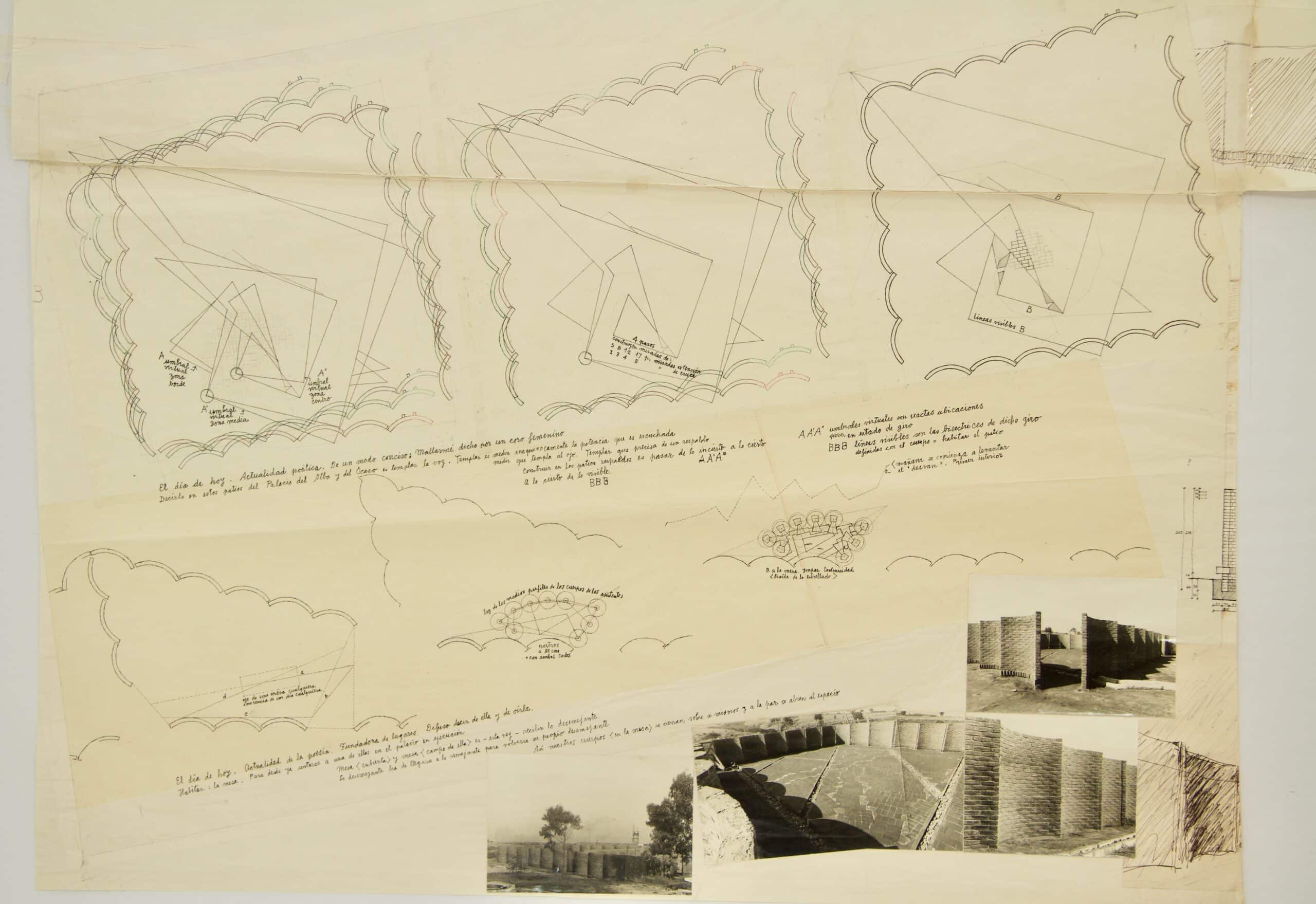

Alberto Cruz presented the principles of The Palace of Dawn and Dusk (Palacio del Alba y del Ocaso) in the Open City’s Music Room on 19 January 1981[1]. While the initial project comprised four lodges with communal rooms, courtyards, and public baths, ultimately, as Cruz describes, following a ‘poetic revelation’ only the courtyards were constructed.

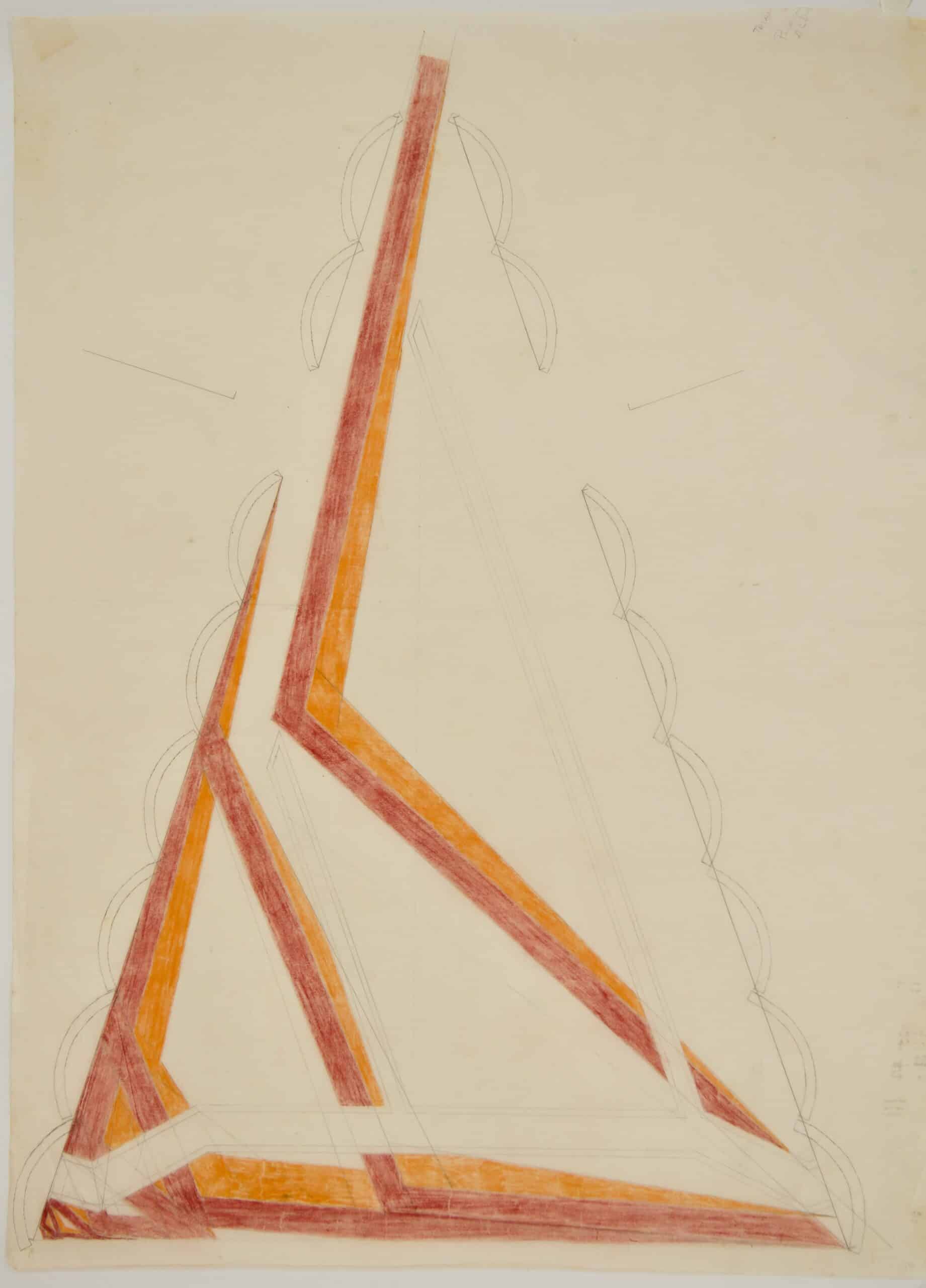

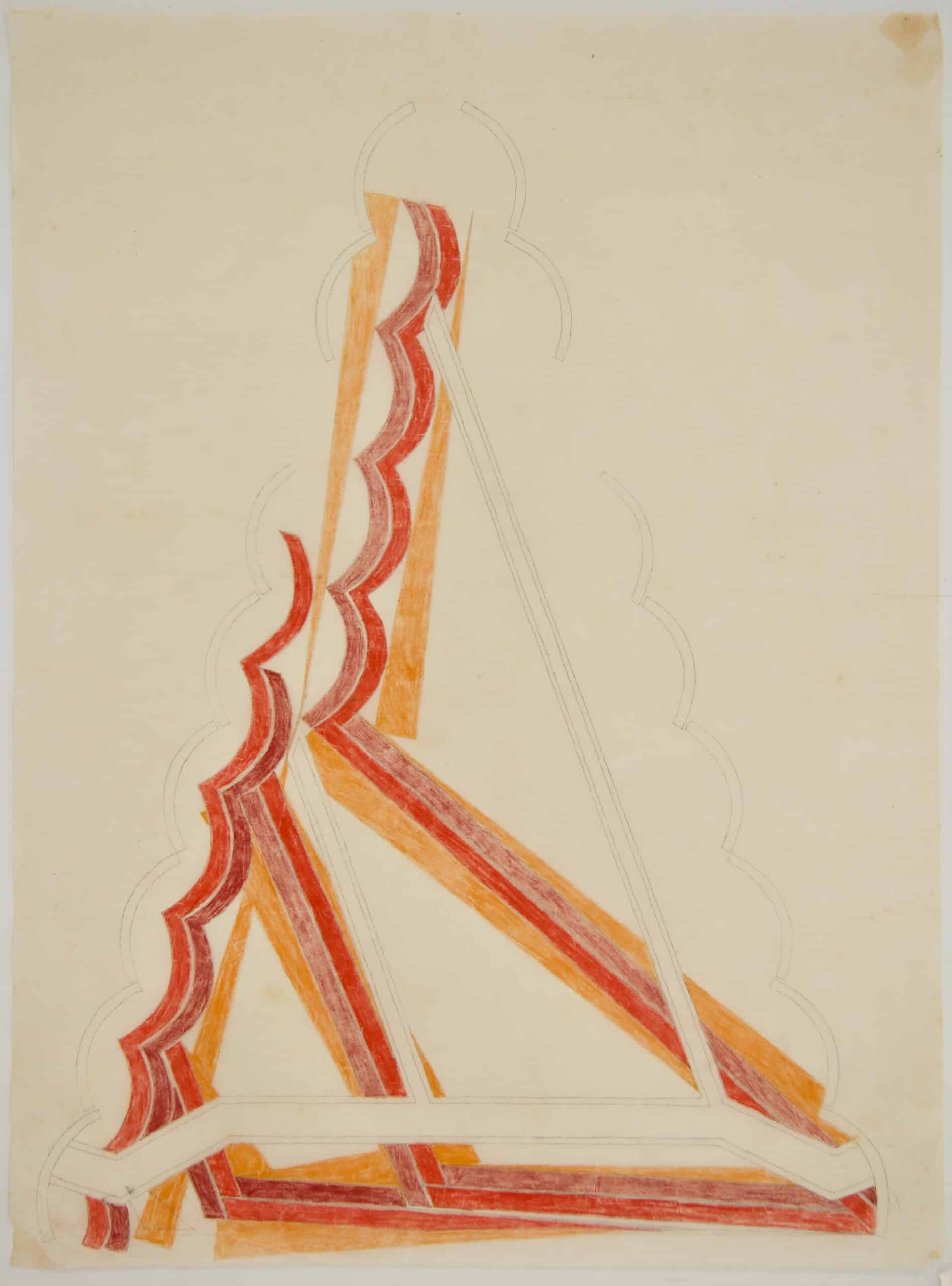

I said to myself, both the dawn and the dusk are moments that we experience unequivocally, unambiguously; at dawn or dusk we would never make the mistake of believing, for example, it was midday. On the other hand, we could easily confuse noontime on a very cloudy day with dusk. And so we experience the dawn and the dusk with exactness. And since they are transitions from darkness to light and vice versa, that have neither too much nor too little of anything, they manifest that exactness as well as a kind of perfection. I took up this idea of perfection and exactness by searching for forms that might build the unequivocal.

To erect the work, I had bricks: the fact of having or not having this or that material is part of the vicissitudes of the foundation of the Open City[2]. I had some bricks that today are calculable in their anti-seismic properties, through self-supporting forms. They are the result and the product of the scientific techniques of contemporary engineering, a field predicated on progress: progress in its domination—the domination of nature. But the dawn and the dusk as forms of the unequivocal, in themselves, cannot be considered as progress in any sense, because they are not born, as we said before, when speaking of the accumulation of knowledge. No; here, we are not talking of the accumulation of any kind of knowledge, but of basking in the occasion; that occasion when the poetry speaks, each time, because poetry will never come to repeat ‘dawn on the inside, dusk on the outside.’

Progress itself is unequivocal; if it weren’t, it simply wouldn’t be progress. As such, engineering and architecture, in this case that of the palace, in this time, battle for the same thing. This is the truth; but it is true because poetry has come to create that possibility. In reality architecture and engineering alone come together in such a way that most often they remain relegated to our most servile works, as it says in Amereida. As such, we are not talking about a relationship between architecture and engineering that is bi=nary, but tri=nary. Accepting, of course, that the binary is a relationship in permanence and this tri=nary is something new each time.

The Palace of Dawn and Dusk was built with the unequivocal aspect of its limits—engineering—and the unequivocal aspect of its void—architecture. But the palace, because it is not a house, could never be something binary. For this reason it received a poetic revelation: to not carry on with the palace itself, to not carry out the four lodges with their communal, shared room; to just leave it with its courtyards, already built, as the antechamber of the future public baths; and for the palace to continue on, as it should, in its surrounding faubourgs that from the start have been waiting for their time to come. We hold, then, that the poetic word does not emerge only as the general origin of the architectural works, nor in an ‘each time’ origination of one of them, but rather that it participates directly in their generation. It participates, we might say, shoulder to shoulder, in the concrete generation of a work.

Anybody can identify the configuration of an architectural work. Anyone may point out that a figure stretches out along the length of a straight line in a bay, or around a square courtyard, or that a figure rises up as a circular tower, etc. For that reason many people believe that man is, naturally, an architect. But that is not so. Because here we are speaking of figures, not forms. The configuration, the figure, represents the calculable aspect of the scope of the work and our involvement in it. Figures are determined by an understanding that does not need to ask about the figure’s geometric generation and origin; their nature is akin to writing in which, surely, we do not ask about the origin and generation of the letters. Of course, there are some architects who started and start working from figures that need to be retraced back to their geometric generation and origin, but in reality those figures are already forms. They are forms, moreover, that evoke their existence as figures. But for that evocation to be truly an architectural evocation, the forms must evoke freely and not mechanically their existence as figures, since architecture is an art in which forms can never be mere figures that ignore what they are, because they do not know the full dimension of the form.

When I talked before about working ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with the poet I didn’t mean it in the realm of figures but very specifically in the realm of form. When the poetic voice said not to continue, it was saying that the form had been consummated. In other words, what had been attempted had already been consummated. This kind of thing is exactly what the poetic word always knows, especially one that knows how to identify places, like Godo’s [Godofredo Iommi] poetic word. But wouldn’t an architect know about all these things? Wouldn’t I know when we have reached the consummation of the form of this palace that was built with the engineering figures of limits and the form of its empty space, which in this case exhibits the form, through that empty space and those limits? In order to respond, let us linger a moment on what was said about the calculable aspect of figures. I mean, in the calculability of the perimeters of the courtyards with their specific quantities of modules of bricks; and of the floors with their compartments in combinations of bricks, in the drainage canals, etc. It is through these kinds of calculables, then, that the form of the unequivocal in this palace comes together. Which, evidently, cannot be built with other figures. At this point, someone might object saying that figure and form here are not two things but one and the same. And I respond: No. Because if someone were to make an exact copy of the palace somewhere, the figure would appear to be the same but in no way would the form be the same. Let’s look at it: the palace, in an extremely calculated manner, traces a horizontal plane at the top of a hill, so that its verticals may unequivocally rise up atop it; but since in an open-air work the horizontal must be done on a slope to allow the rainwater to drain off, this plane was calculated at an angle of 1%, which meant that it had to rest at a maximum of six meters from the network of drainage canals. That 1% and those 6 metres exist in the freedom of choosing of the freedom of Eros—without— the option of the unequivocal. Now, in another place, this horizontal plane would adapt to greater or lesser erosion and accumulation of land, not in the exact lightness it maintains at present. Not in the lightness with which it sits on the land, in the understanding of the equivocal more as a grace that is received rather than a condition that is fulfilled.

It is this received grace that hears the voice—the poetic revelation that points out that what has been attempted—the unequivocal—lies consummated. But, first and foremost, why does she hear? Because one goes in two ways or modes. One, in which what has been created remains in the maternal womb, to put it one way. And another way is outside of oneself, like the children who run their own lives. Now, one hears that part inside of oneself [I have been able to lend form to this over the years, in those little notebooks that I always have with me]. For that reason, that question about whether the architect knows or doesn’t know when what he has attempted has been consummated is, truthfully, not a well-posed question. The architect at once knows and does not know. Or better yet, the architect knows it in a state of openness. It is through the open mind—in the poetic sense—that one may return to not knowing. That is the answer, then, to the question of what exactly happened with this Palace of Dawn and Dusk.

This text has been excerpted and lightly edited from Alberto Cruz: Proyecto, Obra y Ronda (Chile: Fundacion Alberto Cruz Covarrubias, 2021), p. 235 – 6. Drawing Matter would like to thank Sara and Tomás Browne for giving their permission to reproduce the text and illustrations.

Notes

- See David Jolly, ‘The Palace of Dawn and Dusk in the Open City’, in Alberto Cruz: Proyecto, Obra y Ronda (Chile: Fundacion Alberto Cruz Covarrubias, 2021), p. 237 – 9.

- The Open City, or the Cuidad Abierto-Amereida, was the product of the search (termed by Cruz and his collaborators as the Amereida) for the ‘true voice’ of the American continent. The Amereida was undertaken through poetry, drawing, and rigorous observation, and led to the Travesia de Amereida, a journey by the faculty and students of the Instituto de Arquitectura de Valparaíso in 1965, which began in Tierra del Fuego in Southern Chile to Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia.

– Emerald Liu